Tchiloli of S.Tomé or Charlemagne in Africa

Introduction

Before independence, the only Portuguese-speaking country in Africa where local theatre flourished was São Tomé e Príncipe. There, plays of a similar nature were put on in the Ilha do Príncipe, among them the Auto de Floripes, played every year and known among the local people as “São Lourenço” (European in structure like the Tchiloli), and the Danço Congo, known in Angola and African in structure.

Attempts to classify African theatre often come up against epistemological difficulties stemming from the shortage of African specialists. Given this, the point of reference is Corvin (2001, p.37). He considers traditional African theatre as spectacles inspired by traditional culture, where music and dance were linked through the plot of a play. From this angle, it would be possible to classify the Tchiloli here, even though the theme is European. It could even be said that for this reason it has an exemplary character. It represents the problems of bringing harmony between two cultures (the European and the African) which met through historical imperatives but where the African themes managed to rise above the cultural void that came in the wake of a catastrophic meeting. They reinvented through borrowings from European sources and created their own culture, which is nonetheless universal.

Attempts to classify African theatre often come up against epistemological difficulties stemming from the shortage of African specialists. Given this, the point of reference is Corvin (2001, p.37). He considers traditional African theatre as spectacles inspired by traditional culture, where music and dance were linked through the plot of a play. From this angle, it would be possible to classify the Tchiloli here, even though the theme is European. It could even be said that for this reason it has an exemplary character. It represents the problems of bringing harmony between two cultures (the European and the African) which met through historical imperatives but where the African themes managed to rise above the cultural void that came in the wake of a catastrophic meeting. They reinvented through borrowings from European sources and created their own culture, which is nonetheless universal.

Historical framework

The people of São Tomé are of Bantu origin. Their official language is Portuguese, although most of them speak creole.

The inhabitants of the islands are descendants of slaves from the west coast of Africa, with an array of physical, cultural and linguistic features, and Europeans, above all from Madeira. They intermarried and the result is a predominantly half-caste people.

The first colonisation

There were two cycles here. The whole process began with occupation and came to an end around the middle of the 19th century. The first part began when the European settlers arrived and it petered out at the close of the 16th century with the end of the sugar trade and the start of the slave trade.

During this period, the islands were occupied by lower classes and by the children of Jews who had been taken from their parents and forcibly baptised (Mata, 1993). The half-caste mix that stemmed from this became a highly specific socio-cultural class. To quote Mata (1993, p.), “the half-castes were part of two cultures stemming from a specific formation of the local creole society. The process has to be analysed in the context of a specific relationship: local people (owners of land and slaves) / farming (done by slaves). One of the results of this was an aristocratic trend responsible for the typical local attitude (interpreted as innate laziness), which led to a refusal to do farming labour even if paid.

The second colonialisation

This took place in the 19th century and was characterised by the setting up and consolidation of colonial structures with the introduction of new agricultural products (coffee and cocoa), based on the hiring of wage-earners.

At the start of the 20th century, the islands were the biggest producer of chocolate in the world. The estates are the property of a native elite and are soon highly coveted. A process of land expropriation gets under way and although the local people resist, the colonial settlers win out. The estate becomes an institution and, rather like the new type of mill in the 16th century, is not just an agricultural unit with economic purpose but also a socio-cultural construct.

The introduction of new crops and the partitioning of rural property that followed led to a reorganisation of society throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. At the top were the upper middle classes, made up of the large estate owners, and at the base were the wage earners (generally native craftsmen and labourers) and contracted manpower (brought in from Mozambique, Angola and Cape Verde to work on the estates, badly treated and left to live and work in subhuman conditions).

The 19th century was also the period of the second racial mix, with less Portuguese and more African. This became predominant in the way the country was structured and caused big changes in the country’s growth-of-culture processes. At the time, a native of São Tomé was considered to be Portuguese, unlike the inhabitants of Angola, Mozambique and Guinea. They had to show that they had reached a specific “level of assimilation” to become a citizen. This included having a working knowledge of Portuguese (speaking and reading) and habits and behaviour “similar” to the Portuguese.

The universal nature of Tchiloli

It is nonetheless surprising to find on an island in the Atlantic a cultural tradition that is explicitly related to the Portuguese and French and implicitly to the Spanish and Italian.

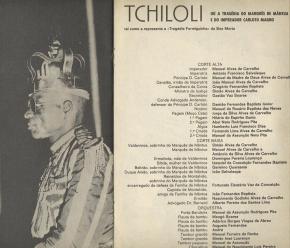

Tchiloli is the creole name for the Tragédia do Marquês de Mântua e do Imperador Carlos Magno (The Tragedy of the Marquis of Mântua and the Emperor Charlemagne). It was written in the 16th century by Baltazar Dias, a blind poet from Madeira. It was also printed in the Romanceiro (XXXVII) of Almeida Garrett, and was a work of medieval inspiration recreated by the people of São Tomé.

It has also been studied by the anthropologist Françoise Gründ, who recently published a work on the subject. There has been a lot of interest shown in France on this traditional spectacle, above all because it is surprising to find a popular work of the Carolingian cycle (no longer found in Europe) on an African island.

In our own times, there is still an obvious power in the São Tomé Tchiloli, including the way it has been moulded to a specific socio-cultural climate. Over the years, it has been an annual enactment, but the groups now put on the play during major local festivals, in the media and even abroad.

In 1973, according to Wallenstein (1974), there were nine Tchiloli groups, although only three were active: Formiguinha da Boa Morte, Florinda de Caixão Grande and Riboque. The groups which put this play on are called Tragédia.

There are currently a dozen groups, though the standard of their work varies a lot.

Borrowings from European sources

The most important of these relate to language and subject matter.

The subject matter is western, but it would be very difficult to find otherwise in a colonial context, since most of the tales are from Lisbon or Coimbra, which is a logical consequence of the assimilation process. From this point of view, what should be highlighted is the choice of justice as a theme, since this is universal and seems to have been important for the survival of the play.

Tchiloli focuses on the concept of royal justice. It brings punishment to D. Carlote for the death of Valdevinos. He is condemned to death and executed at the order of his own father, the Emperor Charlemagne. In fact, the play leads us to infer that the determining factor for its having lasted so long is not so much the Carolingian cycle as the timeless theme of justice.

The African recreation

The African recreation

Tchiloli is a mixture of ceremony, theatre, music and dance characteristic of S. Tomé. In spite of the European aspects of the work, the ritualistic African strands are quite clear and if these had not been recognised and reinterpreted, the work would have been little more than a heavy carnival-style masquerade. To avoid this, African theatre has been studied from many angles to find out what its true nature is. The results, however, have not been encouraging. It is unanimously agreed that an African style of theatre exists but there is no such agreement on what its features are. Without these, some scholars limit themselves to adaptation of studies on the theatre in Europe to the African situation; others, swayed by “source nostalgia” maintain that African theatre is related to traditional ceremonies.

Tchiloli should be seen as emblematic. It is an example of the strength of the popular imagination and has found a solution in which the African cultural heritage has not been negated and other influences have been assimilated to create a spectacle with real African roots.

The African nature of Tchiloli

When we speak of African-ness in terms of the arts, we generally limit ourselves to listing or describing specific points in certain spectacles such as the choreography, language of gestures and so on. There is no analysis of the concepts in the underlying universe which shape these and allow for an understanding of the inherent dynamism in the whole process. African creations cut off from real life, become exotic folklore, providing little understanding of what it is to “be of African roots”. And this also happens with some interpretations of Tchiloli.

The S. Tomé writer Tomaz Ribas (1967), relates Tchiloli to forms of choreography and paradigms that are rooted in Africa, imported with the slave cargo from the western coast. He mentions specifically the Congo-Dance. Seen in this way, African-ness is in the music, the choreography, the singing, the dress, the musical accompaniment, the magic of the dances and the long mime or pantomime scenes. This information is important, but it should not hinder us from analysing some of the common features of modern African spectacles that derive from removing the sacred nature of traditional ceremonies and searching for a common line of development, as we can see in Sang’Amin (1989).

The Characteristics of Tchiloli

Traces of African-ness can be found in Tchiloli, some more explicit than others, and leaving aside exceptions and adaptations, visible when we look at the results of some researchers, among them Carlos Wallenstein (1973) and the anthropologist Françoise Gründ (1990).

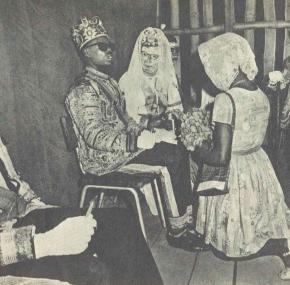

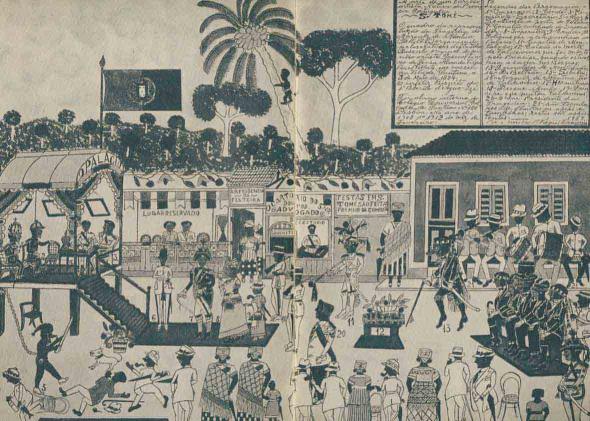

Starting with the regular nature of performances, the importance of this in the African imagination is clear in the fact that it was not put on at regular intervals. It has a ceremonial dimension and is only performed during popular religious festivals or public events. It is long, lasting some 5 to 6 hours. While it is on, people move around from one place to another. At times there are breaks so that the actors can talk to friends or get a bite to eat. It’s as if there were two theatres, face to face but functioning as independent operations.

Its space is universal and the spectator borderline is also part of the spectacle, with the onlookers standing. The chairs are for guests from afar or for town dignitaries.

There are masks in the play. They are oval, smaller than the face, made from moulded mosquito netting, painted white with eyes and mouth picked out. The actors wearing them can only take them off after sunset.

There are masks in the play. They are oval, smaller than the face, made from moulded mosquito netting, painted white with eyes and mouth picked out. The actors wearing them can only take them off after sunset.

The wardrobe has been collected over a long period and is an interesting anachronism. Garments are at times prepared by the players themselves.

The players are farmers and fishermen who do the same parts throughout their lives, the roles being passed on down the generations. The players can act according to how they feel, as long as they do justice to the spectacle. They adapt situations all the time, they even contradict themselves or change according to circumstances, even though these may be fortuitous. They improvise to the best of their ability, and try for maximum effect in their performances. The public picks them up, imitates them, comments aloud on what is going on, a standpoint both aesthetic and critical but involving social and political events in the life of their country.

The music is essential to the spectacle. It backs up the dancing and gives it a reason. For the mime sequences, it underlines the action and propels it forward, meshing in with the players’ movements. The orchestra comprises flutes made of bamboo, drums of various types and sucalos (a native instrument made of a basket with seeds inside).

Symbolism

Tchiloli gives the impression of being a work of popular naivety, but it is in fact an intelligently dissimulated form of cultural resistance.

For the anthropologist Grund (1990), it is a magic ceremony functioning at various levels of codification. In her opinion, Charlemagne symbolises the King of Portugal, far off but tolerated and almost always considered by the local people as a just father for the half-caste children of the land. His son, D. Carloto, is the Portuguese governor of the island, a kind of cynical dictator, a cruel, grasping man, hated by the local people who suffer daily from his behaviour. The Marquis of Mântua is, in fact, the leader of the “children of the land” (the new inhabitants born of the union of white men and slave girls). He brings the first breath of independence, demanding and getting justice. Along with his followers, he represents the half caste families, of high origin, raised to the position of rulers on the plantations and defenders of local interests.

At a different level, the play is a perfect representation of a funeral ceremony in an African country. It has an intrinsic religious side and works as a wake. The only way for local people to keep their identity was to continue to honour their ancestors, but the colonial system did not allow for many expressions of African feeling. The rites of possession terrified the settlers. They put tombs in cemeteries and did not allow them in houses. Given this, you needed a clandestine way of keeping the ties with your ancestors in a surreptitious way. It was as if the Tchiloli groups took the place of the guardians of funeral rites.

At times there is an appeal to the ancestors, with specific sounds and voices (the nasal sound of one of the vigilantes recalls the voice from beyond) and there are sudden switches in situations. All the entries and exits of the players are set out, as is done in African sanctuaries. Even the gestures based on European dance have specific aspects that take it into the African world.

Tchiloli, as a form of artistic expression, has an additional interest. It has created an aesthetic based on picking up left-overs: bits of ribbon, fabric, chocolate paper, mirrors, gilt, home-made gloves, glasses, many-coloured scuptures from the last century, telephones and typewriters. For Gründ, all this material, in permanent renewal, has the symbolic value of luxury. The intensity is the more immense as the materials are so poor. Objects become sacred because the users charge them with a powerful and indisputable inner strength (in the eyes of the players as much as in the eyes of the spectators). They are the symbols of power, coming into their own early from the contacts with foreigners, with whom the local people exchanged minerals or agricultural produce for manufactured goods. Or rather, trinkets that they used as symbols of power in the communities where they lived (as with the mirrors, beads and other items).

Military power is symbolised in the uniforms and white gloves; administrative power in the suits, the telephones, typewriters, glasses and briefcases; the power of knowledge in the student ribbons; all these accessories from our own days show that the problems illustrated in the Tchiloli are an expression of the world of today.

Conclusion

Tchiloli is a story of blood and justice that the local people have made their own. They have turned it into a way to raise their voices against opression but also to retie their links with their African ancestors. Behind the colourful spectacle there is a hidden invocation to their ancestors, in references to a cult that was forbidden under colonial rule. Defeat comes, but there emerges an identity in territory that the first players could take for their own as a means of survival.

Carlos Vaz (1978) states that Tchiloli theatre on S.Tomé is nowadays a popular form of expression, strong and vibrant, a kind of contemporary drama with an effective and unwavering message.

In my view, the countless analyses and studies carried out on Tchiloli are a real indication of the importance of a meeting of cultures. In an ever more global world, we have to know how to co-exist; we must cast out the ghosts of the past, ward off prejudice, and give true value to all forms of culture. Tchiloli has for a long time understood the importance of this spirit for social harmony.

Bibliography

CRUZ, Duarte Ivo

1983, Introdução à História do Teatro Português, Guimarães Editores, Lisboa

GRÜND, Françoise

2006 Le Tchiloli de São Tomé e Prúncipe, Éditions Magellan et Conpagnie, Paris

MATA, Inocência

1993 Emergência e Existência de Uma Literatura, ALAC, Linda-a-Velha

RIBAS, Tomás

1969 Povô Flògá, Camâra Municipal de S.Tomé, S.Tomé

SANG’AMIN, Kapalanga Gazungil

1989 Les spetacles d´’animatiom politique en Republique du Zaire, Cahiers Théâtre Louvain, Bruxelles

SARAIVA, António José e LOPES.Óscar

1985 História da Literatura Portuguesa, Porto Editora, Porto, 5ª Edição

TENREIRO, Francisco José

1950 Aspectos da Colonização da Ilha de S.Tomé, XIII Congresso Luso-Espanhol para o Progresso da Ciências Sociais, Lisbos

1961 A Ilha de S.Tomé, Junta de Investigação do Ultramar/24, Lisboa

VAZ, Carlos

1999 Para um conhecimento do Teatro Africano, Ulmeiro, Lisboa, 2ª Edição

VALVERDE, Paulo,

2000 Máscara, Mato e Morte, Esd. Celta, p.337, Oeiras

Magazines

A.A.V.V.

1990 L’Imaginaire, Revue de la Maison des Cultures de France, nº 14, Paris

A.A.V.V.

1996 Sete Palcos, nº 1, Dezembro de, Coimbra

A.A.V.V.

2006 Camões, nº 19, Instituto Camões, Lisboa, Dezembro

GRÜND, Françoise

1993 « Voilá notre Theatre » in Litterátures du Cap-Vert; de Guiné-Bissao; de São Tomé e Prúncipe,; Notre Librairie, nº112, Janvier-Mars, CLEF, Paris, pp. 118-123

REIS, Fernando

“Teatro Medieval em S.Tomé e Príncipe” in Panorama, nº 23/4º série, pp. 47-49, Lisboa

RIBAS, Tomás

1965 “O Tchiloli ou as Tragédias de S.Tomé e Príncipe” in Revista Espiral, vol 1, ano II, Lisboa

1972 “O Tchiloli ou as Tragédias de S.Tomé e Príncipe” in Boletim do Clube de Teatro de Angola, nº 3, Luanda, 1972

TAVIANI, Ferdinando

1978 «Le Monde du Tiers Théâtre » in Le Courrier de L’UNESCO, Janeiro, pp. 8-15

WALLENSTEIN, Carlos

1974 « Teatro Popular Tradicional » in Colóquio Artes, nº 17, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisboa

in AUSTRAL nº 68, article kindly provided by TAAG - Linhas Aéreas de Angola