To what extent was Sarah Maldoror’s Sambizanga shaped by the ideology of MPLA?

One can argue that Sarah Maldoror’s Sambizanga was shaped, in its entirety, by the Movimento Popular de Libertaҫão de Angola (MPLA). This is unsurprising when one considers Maldoror’s connection to the MPLA and the involvement of key MPLA leaders and guerrillas in the film’s production. This dissertation will argue, firstly, that Sambizanga was shaped, to an extent, by the ideology of the MPLA, primarily its Marxist-Leninist principles.1 It will then argue that Sambizanga was shaped, to a greater extent, by the MPLA’s desire to legitimise the movement and endow it with an external validity.2 Although parts of the film can be read as inflected with the Marxist-Leninist values shared by the MPLA, it was the MPLA’s desire to create a broad appeal within Angola and foster support amongst a wide range of external sponsors, which arguably shaped Sambizanga to the greatest extent. The first chapter of this dissertation will examine the ways in which the MPLA’s ideology, in particular its Marxist-Leninist values, shaped Sambizanga. The second chapter will examine the ways in which the film was shaped, by both Maldoror and the MPLA, as a piece of propaganda, in order to gain international recognition for the injustice of the Portuguese rule in Angola and credibility for the MPLA in the international community. Maldoror has said that she tried to accomplish three things with Sambizanga3: capture a particular movement in the history of the Angolan liberation struggle; create a film that would educate Westerners to the situation in Angola; and tell the story of a revolution from the perspective of a woman.4 This dissertation will argue that these three aims can be linked to the propagandistic elements of the film and the ideology of the MPLA.

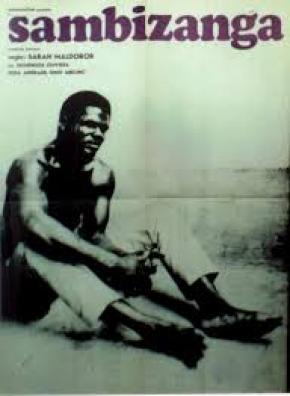

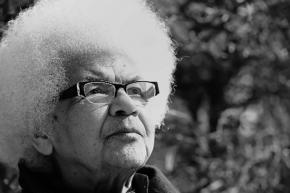

Sarah Maldoror became actively involved in the struggle for African liberation in the late 1950s. It was whilst in Guinea-Conakry, with her husband Mário de Andrade, that she came to realise that in Africa, cinema was the most appropriate medium that could be used to raise political awareness amongst the people, many of whom were illiterate. Thus, Maldoror set out to become a filmmaker. She was awarded a scholarship by the Soviet Union and in 1961 she went to Moscow to study. There she was introduced to the techniques and ideology of Soviet Cinema, under Sergei Gerassimov and Mark Donskoy. In 1963, she became Gillo Pontecorvo’s assistant during the filming of The Battle of Algiers.5 In 1971, Maldoror received $45,000 from the French Centre National du Cinéma and a subsidy from the French Ministry of Cooperation, which helped her finance Sambizanga.6 Sarah Maldoror’s 1972 film, Sambizanga, was adapted by Mário de Andrade, Maurice Pons and Sarah Maldoror from José Luandino Vieira’s 1961 novel, A Vida Verdadeira de Domingos Xavier.7 The film, which takes its name from a black working-class suburb of Luanda, is based on events that took place in 1961, fourteen years prior to Angola’s independence. Shot in the People’s Republic of the Congo, it concerns an Angolan construction worker, Xavier Domingos, imprisoned for secret resistance activity and ultimately beaten to death in jail. The film follows his wife, Maria’s long journey by foot, to locate him, only to find him dead.8 The film interweaves three narrative strands; the martyrdom of Domingos, Maria’s journey, and the efforts of the underground revolutionaries to ascertain the identity of the prisoner.9 The film starts shortly before Domingos is arrested and jailed by the Portuguese authorities. He will eventually be tortured to death for persistently refusing to the name the other members of his resistance movement. Alongside Domingos’s tragic fate, the film shows the plight and determination of his wife, Maria, who sets out on foot in search of her husband. Finally arriving at the Luanda prison, she is informed of his death. The film ends as black activists discuss the forthcoming assault on the Luanda prison, the long-hated symbol of Portuguese oppression.10

Sarah Maldoror became actively involved in the struggle for African liberation in the late 1950s. It was whilst in Guinea-Conakry, with her husband Mário de Andrade, that she came to realise that in Africa, cinema was the most appropriate medium that could be used to raise political awareness amongst the people, many of whom were illiterate. Thus, Maldoror set out to become a filmmaker. She was awarded a scholarship by the Soviet Union and in 1961 she went to Moscow to study. There she was introduced to the techniques and ideology of Soviet Cinema, under Sergei Gerassimov and Mark Donskoy. In 1963, she became Gillo Pontecorvo’s assistant during the filming of The Battle of Algiers.5 In 1971, Maldoror received $45,000 from the French Centre National du Cinéma and a subsidy from the French Ministry of Cooperation, which helped her finance Sambizanga.6 Sarah Maldoror’s 1972 film, Sambizanga, was adapted by Mário de Andrade, Maurice Pons and Sarah Maldoror from José Luandino Vieira’s 1961 novel, A Vida Verdadeira de Domingos Xavier.7 The film, which takes its name from a black working-class suburb of Luanda, is based on events that took place in 1961, fourteen years prior to Angola’s independence. Shot in the People’s Republic of the Congo, it concerns an Angolan construction worker, Xavier Domingos, imprisoned for secret resistance activity and ultimately beaten to death in jail. The film follows his wife, Maria’s long journey by foot, to locate him, only to find him dead.8 The film interweaves three narrative strands; the martyrdom of Domingos, Maria’s journey, and the efforts of the underground revolutionaries to ascertain the identity of the prisoner.9 The film starts shortly before Domingos is arrested and jailed by the Portuguese authorities. He will eventually be tortured to death for persistently refusing to the name the other members of his resistance movement. Alongside Domingos’s tragic fate, the film shows the plight and determination of his wife, Maria, who sets out on foot in search of her husband. Finally arriving at the Luanda prison, she is informed of his death. The film ends as black activists discuss the forthcoming assault on the Luanda prison, the long-hated symbol of Portuguese oppression.10

MPLA ideology: Marxist-Leninist principles

Maldoror has declared that she has “no time for films filled with political rhetoric” and that she is “against all forms of nationalism”, yet despite this disclaimer, Sambizanga can be read as inflected with MPLA values and ideology.11 An attempt to pinpoint the ideological influences on the MPLA leads irrefutably to Marxism-Leninism.12 Marxism-Leninism is an expanded adaptation of Marxism developed by Vladimir Lenin. It is Marxism in the epoch of imperialism and of the proletarian revolution.13 It emphasizes Lenin’s concept of imperialism as the final stage of capitalism and shifts the focus of struggle from developed to underdeveloped countries. Many black Africans found in Lenin’s theory of imperialism a powerful intellectual weapon with which to attack colonial rule.14 The MPLA began as a broad-based anti-colonial movement dedicated to the overthrow of Portuguese colonialism.15 From its formation, it had contained a significant strand of socialist opinion. Important sources of this outlook were the Partido Communista Português (PCP)16 and its Angolan offshoot the Partido Communista Angolano (PCA).17 Key figures in the movement’s early history were either members of these organisations or closely linked to them. Furthermore, the PCP exerted a significant influence over MPLA members resident in Portugal, including Mário de Andrade and Agostinho Neto. Given the strongly pro-Soviet nature of the PCP at that time, links with it enabled those within the MPLA to become acquainted with Marxist-Leninist concepts derived from the Soviet Union. This was bolstered by the establishment of direct links between the movement and the USSR during the 1960s. The MPLA leadership paid frequent visits to Moscow and communist countries trained MPLA cadres which, when combined with the fact that the Soviet Union was the single largest source of military support and adopted an unqualified anti-colonial posture, engendered feelings of ideological sympathy within the MPLA.18

In Sambizanga, Maldoror depicts the MPLA’s Marxist-Leninist principles in three ways: first, through her emphasis on community and the collective endeavour of ordinary people; secondly, through her emphasis on class rather than racial conflict; and thirdly, through her focus on the role of women and their contribution to the overthrow of imperialism. The fundamental question in Marxism-Leninism regards the conditions under which the dictatorship of the proletariat can be won and the conditions in which it can be consolidated.19 In the case of Angola, the MPLA stressed that Portuguese colonialism could only be defeated by an all out struggle waged by a unified front of anti-imperialist forces in Angola,20 which included all members of the community, regardless of class and race. Thus, the film’s central revolutionary theme is that “progress is no longer possible for individuals: only by collective action can the people succeed.”21 Therefore, in Sambizanga, although the narrative is built around an individual protagonist, Maria, Maldoror foregrounds the importance of collective action, that of the underground movement. While revolutionaries may often operate alone or in small numbers, a large organisation, of both urban and rural workers, is necessary for the kind of change that will expel the Portuguese.22 In Sambizanga, it is the importance of collective engagement and action that matters. That is why, although the viewer cannot help but identify and sympathise with Domingos, the militant party member, he is nevertheless killed; it is not the role of the individual to make history, but that of the collective.23 Thus, even though Domingos’s sacrifice is important, in that it serves to unite and mobilise the revolutionaries to attack the prison in Luanda, it is the collective action of the masses which will play the vital role in the development of the revolution. The end of the film, with its increased emphasis on group action, lets the viewer believe that such a change is possible for Angola.24

Sarah MaldororIn Sambizanga, Maldoror is looking at the sources of the strength that would eventually bring Angola victory over the Portuguese. That strength lies in the notion of community, a notion that allows one to synthesise traditional African values with Marxist-Leninist notions of class solidarity. It is this ideal of community which thematically ties together the three plot strands.25 For Maldoror, community is the hope for the future and the family lies at the heart of the community. It is not a self-enclosed unit within a society, but a microcosm of, and an avenue for, the communal values that the ideal society must have.26 Thus, one sees the importance of the scenes of Domingos playing football with the village boys, or of the scenes of Domingos and Maria together at home with their baby. Again, Maldoror emphasises the importance of the community over the individual. Maria and Domingos’s family situation must be sacrificed so that their extended family, the Angolan people, can be liberated.27 The importance of community can be seen in the support that Mama Tete and her people give Maria when she finds herself alone in the strange city. They aid her journey and provide comfort, but more importantly, they remind her that, despite her husband’s death, she still has a son to care for. Despite her loss, the revolution must go on. During the party for the movement activists, Mussunda, a tailor and revolutionary, on hearing of Domingos’s death, urges those gathered to continue their celebrations. Domingos behaved like a true nationalist and while death is honoured, the future cannot be ignored.28 This idea is further reiterated in the final scene, in which a group of Domingos’s fellow construction workers are urged to carry on his work, because activists in the countryside are needed to support the movement’s efforts in the cities. This also represents the allied proletariat of urban and rural workers that Lenin proposed.

Sarah MaldororIn Sambizanga, Maldoror is looking at the sources of the strength that would eventually bring Angola victory over the Portuguese. That strength lies in the notion of community, a notion that allows one to synthesise traditional African values with Marxist-Leninist notions of class solidarity. It is this ideal of community which thematically ties together the three plot strands.25 For Maldoror, community is the hope for the future and the family lies at the heart of the community. It is not a self-enclosed unit within a society, but a microcosm of, and an avenue for, the communal values that the ideal society must have.26 Thus, one sees the importance of the scenes of Domingos playing football with the village boys, or of the scenes of Domingos and Maria together at home with their baby. Again, Maldoror emphasises the importance of the community over the individual. Maria and Domingos’s family situation must be sacrificed so that their extended family, the Angolan people, can be liberated.27 The importance of community can be seen in the support that Mama Tete and her people give Maria when she finds herself alone in the strange city. They aid her journey and provide comfort, but more importantly, they remind her that, despite her husband’s death, she still has a son to care for. Despite her loss, the revolution must go on. During the party for the movement activists, Mussunda, a tailor and revolutionary, on hearing of Domingos’s death, urges those gathered to continue their celebrations. Domingos behaved like a true nationalist and while death is honoured, the future cannot be ignored.28 This idea is further reiterated in the final scene, in which a group of Domingos’s fellow construction workers are urged to carry on his work, because activists in the countryside are needed to support the movement’s efforts in the cities. This also represents the allied proletariat of urban and rural workers that Lenin proposed.

Marxist-Leninist principles are also visible in Maldoror’s emphasis on class divisions as opposed to racial divisions. J. Marcum believes that the fact that a political prism such as Marxism-Leninism was favoured by the leaders of the MPLA may have been a natural consequence of their mestiҫo origins, as it was an ideology that focused on class rather than racial conflict.29 The Ottaways support this conclusion: “The racial characteristics of the MPLA help explain why Marxism held a special appeal for its leaders. By stressing class conflict over all others, it provided the urban mestiҫos and assimilados with an ideology that transcended race and allowed co-operation between them and the black workers and lumpenproletariat of the musseques.”30 Malyn Newitt adds that the mestiҫos, whites and assimilados who formed the MPLA needed a class-based ideology to deflect the accusations that they were not really African at all.31 In Sambizanga, Maria defines the conflict in racial terms, but Mussunda, who is giving lessons in class consciousness to two young revolutionaries, explains that the conflict is between the rich and the poor, and that these divisions are universal. As both Africans and Europeans torture Domingos and share jobs in the revolutionary movement, Maria and the audience learn that political divisions are not the same as racial divisions.32 For example, Silvester, a Portuguese engineer is working with the resistance, whilst Domingos is interrogated by a mestiҫo officer. Thus, when Mussunda announces the death of Domingos to the party, he starts out: “My fellow Africans…,” but on seeing Silvester, he starts afresh: “My fellow Angolans…”33

Finally, Marxist-Leninist principles are visible in Maldoror’s focus on the role of women and their contribution to the struggle against colonialism. Marxism-Leninism strove for the liberation of women. Under colonial rule, women were doubly oppressed; first, as women and, then, as colonized subjects.34 Under Marxism-Leninism, women were seen as equals of men and it was believed that their biological differences should not limit their involvement within society. Furthermore, Lenin believed that no revolution was possible without the participation of women, a belief that Maldoror has reiterated.35 Thus, Sambizanga is aimed at giving credibility to woman’s involvement in the revolutionary struggle36 through the central role given to Maria in the film and Maldoror’s decision to tell the story of a revolution from the perspective of a woman, a point of view normally neglected in such films.37 Firstly, the screenwriters chose to alter the story, putting more emphasis on the experience of Domingos’s wife, Maria. Not only that but, in Sambizanga, Maria is a stronger character: in the novel she becomes so discouraged as to abandon her search for Domingos twice, whilst in the film she carries on without flinching.38 Maria is not only a victim, but also hope for the future. Although she is a traditional wife and mother, and Domingos keeps his political activities a secret from her, by the end of the film, she has become aware of the revolutionary struggle. She is never seen to reflect on the events but historically, women did go on to play a central role in the Angolan struggle for independence.39 Furthermore, the film depicts, through the characters of Maria and Mama Tete and their roles, a return to the communal, matrifocal societies, which colonialism replaced with patriarchal societies. The film portrays the “sense of collectivity” amongst the women,40 acutely captured with a lingering camera that focuses, for nearly two minutes41, on the women’s emotion-laden faces whilst mourning the death of Domingos.42 The women in mourning are in stark comparison to the men playing cards at the table behind them, seemingly unconcerned. Maria is crucial to the film in the way that she both embodies and provokes the communal ideal.43 Moreover, Marxism-Leninism was opposed to the degradation of women by their husbands and in Sambizanga, Domingos is a model husband and father; the scenes of him at home deliberately demonstrate his love for his wife and child. Finally, Lenin refers to the suffering and deprivations borne by women.44 In Sambizanga, Maria is often shot with a telephoto lens, which flattens the background behind her and has the added effect of making her trip seem even longer, emphasising her suffering, as on her eventual arrival, she is only to find out that her husband is already dead.

The aforementioned scenes of Domingos playing football, a male dominated sport, and playing with the baby, and the fact that Maria’s heroism is treated differently to Domingos’s appear to go against Marxism-Leninism as they reinforce traditional family roles and conservative gender politics. Maria is always present when Domingos spends time with the baby; a man cannot be left with full responsibility for a child, as childcare is a woman’s role. Whilst Domingos is praised as a true nationalist, Maria is simply reminded that she must care for her son. However, one can argue that it is Marxism-Leninism, but under a different social reality – a traditional African social reality. It is a compromise between the two. The film can still be seen as a challenge to sexist patriarchal expectations. For instance, when Domingos, the male head of the family is arrested, Maria, the woman has to assume a heroic role. Moreover, although Maria’s support network is all female, which would have traditionally been the case, the role that Mama Tete and the other women play is more than the customary supportive role played by women. Rather than simply console her, they encourage her to search for her husband. Furthermore, one can argue that Maria’s role is less one of immediate heroism and more one of gradual heroism. In the wake of tragedy, she must remain strong for her son, as their contribution will be necessary in the future. Her son, and others like him, is Angola’s future and his growth may symbolise the rebirth of Angola, free from colonial oppression.

Some have claimed that Sambizanga is a feminist film. However, it can be argued that in no way is the film characterised as primarily feminist. There are aspects which could be viewed as feminist, however, these can arguably also be characterised, more convincingly, as Marxist-Leninist values. For feminists, women come before socialism. This, however, is not the case with Sambizanga. Feminist ideology states that the centrality of the family is the root of women’s oppression. However in Sambizanga, there is a great focus on the family. The many communities that made up Angola would have had different customs and beliefs; however, their views on the family and a woman’s role would more than likely have been the same. In attempting to build a national consensus, putting the freedom of women above other aspects of Marxist-Leninist ideology could have been difficult. Thus, to Maldoror and the MPLA, the role of the family and community as central to Marxism-Leninism are more important than the family’s oppression of women. Hence why, in Sambizanga, the traditional family is not questioned as a form of oppression. Whilst Maldoror has said that “she is not actively involved in any woman’s movement”, her involvement in the MPLA is clear to see.45

When analysing what shaped Sambizanga one must note that Maldoror’s husband and fellow scriptwriter, Mário de Andrade, was former President of the MPLA; the film was funded, in part, by the MPLA; and the cast of non-professional actors included MPLA militants.46 One can argue therefore that Marxist-Leninist values could not fail to influence and shape the film.

MPLA propaganda

Despite the fact that Marxism-Leninism was undoubtedly the most pervasive political influence on the early development of the MPLA’s ideology, in order to ensure a broad appeal within Angola and foster support amongst a wide range of external sponsors47, the movement’s leadership often deliberately downplayed its socialist orientation.48 The competitive pressures of legitimisation wielded an overwhelming influence; the MPLA was one of three nationalist groups in Angola and there was pressure to endow the movement with an internal and external validity.49 In 1962, Andrade and the MPLA were finding overt communist associations to be a handicap in terms of international support and united action with other Angolan political movements.50 So, although one can argue that the aforementioned links between the PCA and the MPLA are clearly long-standing, Viriato da Cruz – Secretary-General of the MPLA – claimed that “the PCA…had no appreciable influence in either the preparation or the launching of the Angolan revolutionary movement”.51 Also, MPLA historiography omits any reference to the PCA52, probably in the interests of appearing to be a broader political movement and thereby appealing to a wider range of internal and external support.53 Accordingly, the MPLA’s programme, adopted in 1961 and updated in 1974, contained not a single explicit reference to socialism.54 It was not until it had established itself in a position of political supremacy in 1975, that the movement’s leadership became more confident in asserting a clear ideological line. The programmatic documents of the MPLA thereafter contained an indisputable commitment to a socialism which reflected a clear appreciation of Soviet-style Marxism-Leninism. In 1977, at its first congress, the movement formally established itself as a ‘Marxist-Leninist party…structured in accordance with Marxist-Leninist principles.’55

Sambizanga can be seen to be shaped by the MPLA’s desire to legitimise the movement and endow it with an external validity in a number of ways. Firstly, it can be seen in the fact that it is not overtly political. One would expect a film which is partly funded by the MPLA and influenced by Marxist-Leninist ideology to be overtly pro-MPLA and pro-Marxism-Leninism. However, Sambizanga is not. One can argue that this is because Maldoror had to be sensitive to the international reception of the film. The film was not made to be shown in Angola - it could not be shown in the country until after independence - and Maldoror did not only seek support from the Soviet Union, but also support from opponents of the Soviet Union, such as the United States. Therefore, an overtly political film with a clear link to Marxism-Leninism would not have been effective. Thus, the film was made in support of the MPLA but rather than focusing on this political movement specifically, it focuses on the liberation struggle in a wider sense and crass political content and comment are subdued. Maldoror’s adoption of a more subtle approach was, for the most part, a success.56 It lead to both the wide distribution of Sambizanga in the Eastern-bloc countries, whose intellectuals tended to be pro-MPLA, and very positive reviews in the capitals of Europe and in New York.57 Furthermore, the film won the Tanit D’Or at the 1972 Carthage Film Festival,58 a show of support for the Angolan independence struggle and for her particular interpretation of the struggle.59

In consideration of the previous point, one can argue that, secondly, Maldoror sought to gain global recognition of the injustice of Portuguese rule in Angola and create conviction for the MPLA and Angola’s cause by encouraging empathy, for those involved, amongst the audience. In Sambizanga, this can be seen in the fact that Maldoror portrays the Portuguese officials in a negative light. During Domingos’s interrogation, the white Portuguese official plays the ‘bad cop’, calling him a filthy nigger and beating him brutally, whilst the mestiҫo official plays the ‘good cop’, in as far as he does not beat him. Thus, Maldoror avoids representing the African man as the brutal one. Furthermore, at the headquarters of the political police, Maria is thrown out and sworn at by a couple of Whites in civilian dress. On the other hand, she seeks to portray the Angolans and the revolutionaries in a positive light. Domingos is a good Angolan because he is a good family man. The previously mentioned scenes of Domingos playing soccer with the village boys and of Domingos and Maria together at home with their baby demonstrate this. Consequently, when the Land Rover comes to break up the family, viewers are outraged. These scenes also establish the ideal for which the nationalist forces are fighting. In opposition to the brutality of the Portuguese, the strength of the nationalist forces lays in the affection that they have for one another and the sense of community. This affection is seen throughout the film: in the comfort given to Maria by the other village women when Domingos is taken; in the way that young Zito leads old Petelo around the city, despite the taunts of the other children; in the support that Mama Tete and her people give Maria when she finds herself alone in Luanda; and in the caring that we see when the prisoners bathe blood from Domingos’ tortured body.60 The communal sharing of food, nursing and anguish speaks more strongly to a wider audience than a heavy-handed political point.61 Furthermore, in the scene in which Domingos delivers the movement’s new revolutionary leaflet to his friend, Maldoror draws the audience’s attention to the mutual suffering faced by Angolans by having him read it aloud: “hunger in our homes, poverty in our huts, forced labour on the road gangs. All this is due to Portuguese colonialism.” The resistance forces are therefore portrayed as unambiguously righteous whilst, on the other hand, the Portuguese colonial forces, with their thoroughly abject native police and informers are unambiguously evil.62 In this way, Maldoror also aims to vindicate the later actions of the MPLA revolutionaries.

To illustrate the previous two points further, one can analyse the influence of politically engaged Soviet Cinema on Sambizanga. Despite the influence of Sergei Eisenstein, a director within the Soviet Union committed to Marxism-Leninism, and his 1925 film, Battleship Potemkin, Maldoror created a far from politically forthright film. It is true that as a filmmaker outside the Soviet Union, Maldoror could be more experimental in her work and had more licence to form the semantic substance of the film. However, with the influence of such highly political films, one could arguably expect Sambizanga to be more doctrinaire. In view of this restraint, one can reiterate the argument that Maldoror desired to create a much more internationally accessible film. Many comparisons can be drawn between Sambizanga and Battleship Potemkin, both in terms of style and in terms of their political significance.63 However, Sambizanga is a far more subtle film. Maldoror employs many of the same techniques to evoke feelings of sympathy from the audience in Sambizanga, as Eisenstein does in Potemkin, yet she avoids Potemkin’s overt polemic. Potemkin presents a dramatized version of the mutiny that occurred in 1905 when the crew of the Russian battleship Potemkin rebelled against their officers of the Tsarist regime. The film was written as a revolutionary propaganda film and it has been named one of the most influential propaganda films of all time. Both films are set in a pre-revolutionary time and use the death of a worker-hero to galvanize people into unified action. Like most propaganda, the characterisation in both films is simple, so that the audience can clearly see with whom they should sympathize. Both films also attempt to influence political thought through emotional response. Eisenstein used film editing in such a way as to produce a heightened emotional response, so that the viewer would feel sympathy for the rebellious sailors of the battleship Potemkin and hatred for their cruel overlords. As well as the aforementioned techniques, another way in which Maldoror creates an emotional response is her use of pacing. In many Russian films, pacing is a means of didacticism; a political tool. Slow scenes and the unravelling of slow sequences of action allow thought processes and rituals to unfold almost in real time. A pensive quietness is created which prompts thought in the audience, and according to revolutionary maxims, thought leads to action. In the film, Maria’s journey to save her husband Domingo is slow and frustrating as she is repeatedly thwarted by the Portuguese authorities. Maldoror alternates the scenes of beatings in the prison, as Domingo edges closer to his brutal death, with scenes of Maria, as she becomes increasingly exhausted, running from police station to town office, searching for her husband. Through frustration, Maldoror creates an unavoidable support for the liberation movement in Angola.64 Potemkin assaults the viewer’s sensibilities with forceful melodrama and rhythmic editing. For example, the massacre on the steps, which never took place, was inserted by Eisenstein for dramatic effect and to demonise the Imperial regime. Sambizanga lacks these melodramatic elements. For instance, rather than exaggerate the depiction of the PIDE’s interrogation techniques, Maldoror ensures that it is absolutely consistent with the accounts given by surviving victims of interrogation. Maldoror’s approach is more understated. Throughout most of Maria’s journey, Maldoror uses a telephoto lens that compresses the space, blurs the countryside, and separates characters from their surroundings. This is the visual equivalent of the Angolan people’s social and political situation. Although their country is rich, the people are prevented from taking any meaningful part in defining its future or distributing its wealth.65 By creating her point visually, Maldoror avoids any direct political statements. In both films, many scenes are calculated to elicit specific responses and, do succeed, but whilst in Potemkin, this creates a certain feeling of manipulation, in Sambizanga; such a feeling is less present. For example, Eisenstein’s use of violence creates a shock value which Sambizanga lacks. Moreover, in the Odessa steps sequence in Potemkin the average length of each shot is about two seconds, barely giving the viewer a chance to breathe amongst the chaos. Whilst Eisenstein uses montage to guide the audience to the ultimate ideological conclusion, Maldoror creates space for reflection and allows the audience time to grow in understanding.66 Furthermore, she allows time for the characters to grow in identity. For instance, in the scene in which the male revolutionaries receive news of Domingos’s death, the camera focuses on the men’s faces for over two minutes. These close-ups convey the sorrow and confusion which, in time, becomes determination and leads to the increasing militancy of the people.

Sarah MaldororOne can argue that Maldoror’s decision to set the film in 1961, rather than 1972, was also a propagandistic decision, made to portray the MPLA in the best possible light. By setting the film in 1961, Maldoror avoided the complications of the MPLA’s later position. The decision allowed her to create a foundational narrative about the origins of the struggle for independence and the very early years of the MPLA, making the struggle appear clearer cut than it had become by the 1970s. It can be argued that 1961 was a better, more idealised time for the MPLA, certainly for Mario de Andrade and those around him. In 1972, when the film was being made, the anti-colonialist struggle was going nowhere, and the MPLA had proved most vulnerable to renewed internal divisions. Andrade himself had been moved increasingly to the fringes of MPLA decision-making as a result of his differences with Agostinho Neto, the new leader. Furthermore, the MPLA was expending a good deal of effort fighting its rival nationalist groups, Holden Roberto’s FNLA and Jonas Savimbi’s UNITA, rather than the Portuguese.67 In 1963, Mário de Andrade stood down from the presidency of the movement, but remained within it. The MPLA had suffered weak leadership and inefficient organisation whilst under his control. By the early 1970s, the MPLA logistical situation had become so hopeless that the leadership began to fall apart, with violent rivalry breaking out along ethnic, ideological and class lines.68 In the end, two rebellious factions split from the party. Between 1970 and 1972, divisions within the MPLA began to re-emerge with a consequent fall in its military effectiveness. In 1972 conflict flared between its military leader in the eastern region, Daniel Chipenda, and Agostinho Neto. This was soon followed by the re-opening of ideological differences between Neto and Mário de Andrade. The immediate impact on the MPLA was a sharp reduction in Soviet aid as Moscow came to question the potential returns to be achieved from its beneficence.69 In 1972-73, the Portuguese carried out extensive sweeps in eastern Angola. These attacks amounted to a major defeat for the MPLA and in 1973 Neto had to withdraw some 800 of his guerrillas to the safety of the Congo.

Sarah MaldororOne can argue that Maldoror’s decision to set the film in 1961, rather than 1972, was also a propagandistic decision, made to portray the MPLA in the best possible light. By setting the film in 1961, Maldoror avoided the complications of the MPLA’s later position. The decision allowed her to create a foundational narrative about the origins of the struggle for independence and the very early years of the MPLA, making the struggle appear clearer cut than it had become by the 1970s. It can be argued that 1961 was a better, more idealised time for the MPLA, certainly for Mario de Andrade and those around him. In 1972, when the film was being made, the anti-colonialist struggle was going nowhere, and the MPLA had proved most vulnerable to renewed internal divisions. Andrade himself had been moved increasingly to the fringes of MPLA decision-making as a result of his differences with Agostinho Neto, the new leader. Furthermore, the MPLA was expending a good deal of effort fighting its rival nationalist groups, Holden Roberto’s FNLA and Jonas Savimbi’s UNITA, rather than the Portuguese.67 In 1963, Mário de Andrade stood down from the presidency of the movement, but remained within it. The MPLA had suffered weak leadership and inefficient organisation whilst under his control. By the early 1970s, the MPLA logistical situation had become so hopeless that the leadership began to fall apart, with violent rivalry breaking out along ethnic, ideological and class lines.68 In the end, two rebellious factions split from the party. Between 1970 and 1972, divisions within the MPLA began to re-emerge with a consequent fall in its military effectiveness. In 1972 conflict flared between its military leader in the eastern region, Daniel Chipenda, and Agostinho Neto. This was soon followed by the re-opening of ideological differences between Neto and Mário de Andrade. The immediate impact on the MPLA was a sharp reduction in Soviet aid as Moscow came to question the potential returns to be achieved from its beneficence.69 In 1972-73, the Portuguese carried out extensive sweeps in eastern Angola. These attacks amounted to a major defeat for the MPLA and in 1973 Neto had to withdraw some 800 of his guerrillas to the safety of the Congo.

Thus, the Portuguese collapse in 1974 came just in time to save the MPLA from disaster.70 Furthermore, by setting the film in 1961, Maldoror avoids discussing the military actions of the MPLA. From 1966 onwards, in the areas it controlled near the eastern frontier, the MPLA commanders implemented a policy of terror in order to cow the local population.71 There were numerous executions not only of people suspected of having links with the Portuguese but of anyone accused of causing disunity. The realities of this reign of terror in the eastern region, where most of the MPLA commanders and fighters were strangers, were far removed from the image of a humanitarian, modernising socialist party portrayed in their propaganda.72 Moreover, by setting the film in 1961, Maldoror can close on a rebel’s declaration that they will attempt to free the political prisoners from the Luandan prison on February 4th. She wants her audience to leave on a wave of revolutionary potential and so it is appropriate that she does not portray the results of the 1961 rebellion.73 One can argue that Maldoror decided to include reference to the 4th February, 1961 rebellion because the revolt gave much greater international publicity to emerging nationalist leaders,74 as the world press became interested in Angola and its exiled nationalist leaders.75 It is claimed that the MPLA actually played no role in the organisation of the uprising, but immediately took credit for staging the armed insurrection, and thereby won a certain credibility in the international community, among people who wanted to believe in the existence of an active Angolan nationalist movement.76 However, arguably she does not depict the rebellion itself, as it was far from successful and in the aftermath of the revolt, the tentative national leadership was cowed.77 Moreover, the rebellion unleashed an outbreak of violence. Killing became a weapon which, once introduced, became a permanent feature of the political scene.78 From 4th February to the end of 1961, about 1200 Portuguese and 50,000 Africans died as a result of rioting, massacres, mass executions, and torture, with another 128,000 Africans fleeing to the Congo.79

In a war in which external perception was becoming as important as concrete military achievement, the MPLA took all available opportunities to enhance their political image. One can argue therefore that their desire to legitimise the movement and endow it with an external validity could not fail to influence and shape the film.

Conclusion

Sarah Maldoror’s Sambizanga was shaped, to an extent, by the MPLA’s ideology. The first chapter of this dissertation has demonstrated the influence of the MPLA’s Marxist-Leninist principles through analysis of their depiction in the film. With Maldoror’s personal connection to the MPLA and the involvement of key MPLA leaders and guerrillas in the film’s production, the MPLA’s ideology, specifically its Marxist-Leninist principles, were undoubtedly going to shape the film to an extent. However, Sambizanga was shaped, to a greater extent, by the MPLA’s desire to legitimise the movement and endow it with an external validity.80 As explored in the second chapter, the film’s propagandistic elements and the fact that the MPLA deliberately downplayed its socialist orientation demonstrate that, in 1972, the movement’s global political image was more important than a strict adherence to Marxist-Leninist principles. Maldoror has stated that she had three aims for the film: to capture a particular movement in the history of the Angolan struggle for independence; to create a film that would educate Westerners to the situation in Angola; and to tell the story of a revolution from the perspective of a woman. One can argue that whilst the influence of the MPLA’s adherence to Marxism-Leninism can be seen to shape her final aim, it is the desire to garner support for Angola’s liberation struggle and the MPLA’s role in that struggle, which shaped the other two. Therefore, it was the MPLA’s desire to create a broad appeal within in Angola and foster support amongst a wide range of external sponsors which arguably shaped Sambizanga to the greatest extent.

Bibliography

Works and sources cited:

Abbott, P. and M. Rodrigues, Modern African Wars 2: Angola and Mozambique 1961-74, 1998, Osprey Publishing

Birmingham, D., Frontline Nationalism in Angola & Mozambique, 1992, England: James Currey Publishers Ltd.

Chabal, P. and N. Vidal (ed.) Angola: The Weight of History, 2008, Columbia University Press

Chabal, P., A History of Postcolonial Lusophone Africa, 2002, C. Hurst & Co. Ltd

Cummings, B. L., ‘African Cinema and Soviet Filmmaking’, Film Africa 2012, 18 October 2012, [Online] Available: <http://www.filmafrica.org.uk/blog/african-cinema-and-soviet-filmmaking> [Last accessed: 7/5/013]

Dembrow, M., ‘Sambizanga and Sarah Maldoror’, 2006, [Online] Available: <http://spot.pcc.edu/~mdembrow/sambizanga.htm>, [Last accessed: 7/5/2013]

Diop, S., ‘Sambizanga’, Directory of World Cinema, [Online] Available: <http://worldcinemadirectory.co.uk/component/film/?id=878> [Last accessed: 7/5/2013]

Gugler, J., ‘African Writing Projected onto the Screen: Sambizanga, Xala and Kongi’s Harvest’, African Studies Review, Vol. 42, No. 1 (April, 1999), African Studies Association, pp. 79-104

Guimarães, F. A., The Origins of the Angolan Civil War: Foreign Intervention and Domestic Political Conflict, 2001, Macmillan Press Ltd.

Hughes, A., (ed.) Marxism’s Retreat from Africa, 1992, Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

Hungwe, E; Hungwe, C., ‘Interrogating Notions of Nationhood, Nation and Globalisation in Postcolonial Africa: A Textual Analysis of Four African Novels’, 2010, [Online article], 452ºF. Electronic journal of theory of literature and comparative literature, 2, 30-47, Available: < http://www.452f.com/index.php/en/elda-hungwe—chipo-hungwe.html> [Last accessed: 7/5/2013]

Kerbel, M., ‘Angola: Brutality & betrayal’, The Village Voice, 6 December 1973, [Online] Available: <http://news.google.ca/newspapers?id=pFQQAAAAIBAJ&sjid=MowDAAAAIBAJ&pg=6244,5229471&dq=sarah-maldoror&hl=en> [Last accessed: 7/5/2013]

Krohn, L., ‘On Film Political, Poetic ‘Sambizanga’’, Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume XCVIII, Number 45, 21 November 1973, [Online] Available: <http://spectatorarchive.library.columbia.edu/cgi-bin/columbia?a=d&d=cs19731121-01.2.19&srpos=&dliv=none&e=––-en-20—1801—txt-IN-swimming–> [Last accessed: 7/5/2013]

Lawrence and Wishart, What is Leninism?, London: Lawrence and Wishart

Macqueen, N, The Decolonization of Portuguese Africa: Metropolitan Revolution and the Dissolution of Empire, 1997, Addison Wesley Longman Limited

Maldoror, S., Sambizanga, (Angola, 1972, 1h42m) [Online] Available: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TVXWIBmjkSg&feature=youtu.be>, [Last accessed: 7/5/2013]

Marcum, J., The Angolan Revolution, Volume I, The Anatomy of an Explosion (1950-1962), 1969, Cambridge (Mass.) London: The M.I.T. Press

Martin, M. T., (ed.) Cinemas of the Black Diaspora: Diversity, Dependence, and Oppositionality, 1995, Wayne State University Press

Moorman, M., ‘Of Westerns, Women, and War: Re-Situating Angolan Cinema and the Nation’, Research in African Literatures, Vol. 32, No.3, Nationalism (Autumn, 2001), Indiana University Press, pp.103-122 Mulcaire, T., ‘February 4’, Cabinet Magazine, [Online article], Issue 2 Mapping Conversations Spring 2001, Available: <http://cabinetmagazine.org/issues/2/februaryfourth.php> [Last accessed: 7/5/2013]

Noth, D. P., ‘Film Gets Grip on a Revolution’, The Milwaukee Journal, 11 April 1978 [Online], Available: <http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=HWkaAAAAIBAJ&sjid=jSkEAAAAIBAJ&pg=6349,1115403&dq=sarah-maldoror&hl=en> [Last accessed: 7/5/2013]

Ottoway, D. and M., Afrocommunism, 1986, New York: Africana Publishing

Pfaff, F., From Twenty-Five Black African Filmmakers: A Critical Study, with Filmography and Bio-Bibliography, 1988, Greenwood Press

Quart, B., Women Directors: The Emergence of a New Cinema, 1989, ABC-CLIO

Russell, S. A., Guide to African Cinema, 1998, Greenwood Press

Schmidt, N. J., ‘African Literature on Film’, Research in African Literatures, Vol. 13, No. 4 (Winter, 1982), Indiana University Press, pp. 518-531

Swanson, S., Reel Women: Episode 2: Sambizanga, African Film Podcasts, SOAS Radio, 29 June 2012, [Online], Available: < http://soasradio.org/content/reel-women-episode-2-sambizanga> [Last accessed: 7/5/2013]

Ukadike, N. F., ‘Reclaiming Images of Women in Films from Africa and the Black Diaspora’, Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, Vol. 15, No. 1, Women Filmmakers and the Politics of Gender in Third Cinema (1994), University of Nebraska Press, pp. 102-122

Zetkin, C., ‘Lenin on the Women’s Question’, [Online], Available: <www.marxists.org> [Last accessed: 7/5/2013]

For further reading:

Brinkman, I., ‘War, Witches and Traitors: Cases from the MPLA’s Eastern Front in Angola (1966-1975), The Journal of African History, Vol. 44, No. 2, (2003) pp. 303-325, Cambridge University Press

Kay. K and G. Peary, (ed.) Women and the cinema: a critical anthology, 1977, New York: Dutton

Marcum J., The Angolan Revolution, Volume II, Exile Politics and Guerrilla Warfare (1962-1976), 1981, Cambridge (Mass.) London: The M.I.T. Press

Raby, D. L., Fascism & Resistance in Portugal: Communists, liberals and military dissidents in the opposition to Salazar, 1941-1974, 1988, Manchester: Manchester University Press

Taylor, R., The Battleship Potemkin: The Film Companion, 2000, I.B.Tauris

Notes:

1 M. Moorman, ‘Of Westerns, Women, and War: Re-Situating Angolan Cinema and the Nation’, p.110

2 F. A. Guimarães, The Origins of the Angolan Civil War: Foreign Intervention and Domestic Political Conflict, p.45

3 For further reading see a short explanatory piece by Maldoror on Sambizanga: S. Maldoror, ‘On Sambizanga’, pp.305-310 in K. Kay, Women and the Cinema: A Critical Anthology

4 M. Dembrow, ‘Sambizanga and Sarah Maldoror’

5 F. Pfaff, Twenty-five Black African Filmmakers: A Critical Study with Filmography and Bio-Bibliography, p.206

6 F. Pfaff, Twenty-five Black African Filmmakers: A Critical Study with Filmography and Bio-Bibliography, p.207

7 N. J. Schmidt, ‘African Literature on Film’, p.527

8 B. Quart, ‘Women Directors: The Emergence of a New Cinema’, p.256

9 J. Gugler, ‘African Writing Projected onto the Screen: Sambizanga, Xala and Kongi’s Harvest’, pp.81-82

10 F. Pfaff, Twenty-five Black African Filmmakers: A Critical Study with Filmography and Bio-Bibliography, p.211

11 M. Moorman, ‘Of Westerns, Women, and War: Re-Situating Angolan Cinema and the Nation’, p.110

12 F. A. Guimarães, The Origins of the Angolan Civil War: Foreign Intervention and Domestic Political Conflict, p.45

13 Lawrence and Wishart, What is Leninism?, London, p.12

14 A. Hughes, (ed.) Marxism’s Retreat from Africa, p.4

15 A. Hughes, (ed.) Marxism’s Retreat from Africa, p.12

16 For further reading on the PCP see: D. L. Raby, Fascism & Resistance in Portugal: Communists, liberals and military dissidents in the opposition to Salazar, 1941-1974

17 For further reading on the PCA see: J. Marcum, The Angolan Revolution, Vol. I, The Anatomy of an Explosion (1950-1962), pp.27-28

18 M. Webber, ‘Angola: Continuity and Change’, Marxism’s Retreat from Africa, p.127

19 Lawrence and Wishart, What is Leninism?, London, pp.22-23

20 E. Hungwe; C. Hungwe, “Interrogating Notions of Nationhood, Nation and Globalisation in Postcolonial Africa”, p.35

21 M. Kerbel, ‘Angola: Brutality & betrayal’, p.85

22 S. A. Russell, Guide to African Cinema, p.127

23 Michael T. Martin, (ed.) Cinemas of the Black Diaspora: Diversity, Dependence, and Oppositionality, p.85

24 S. A. Russell, Guide to African Cinema, p.127

25 M. Dembrow, ‘Sambizanga and Sarah Maldoror’

26 M. Dembrow, ‘Sambizanga and Sarah Maldoror’

27 M. Dembrow, ‘Sambizanga and Sarah Maldoror’

28 S. A. Russell, Guide to African Cinema, p.127

29 F. A. Guimarães, The Origins of the Angolan Civil War: Foreign Intervention and Domestic Political Conflict, pp.45-46

30 D. and M. Ottoway, Afrocommunism, p.101

31 M. Newitt, ‘Angola in Historical Context’. In Angola: The Weight of History, p.74

32 S. A. Russell, Guide to African Cinema, p.126

33 J. Gugler, ‘African Writings Projected onto the Screen: Sambizanga, Xala and Kongi’s Harvest’, p.82

34 S. Diop, ‘Sambizanga’, Directory of World Cinema,

35 S. Swanson, ‘Reel Women: Episode 2: Sambizanga’, 5min 03secs

36 N. F. Ukadike, ‘Reclaiming Images of Women in Films from Africa and the Black Diaspora’, p.111

37 M. Dembrow, ‘Sambizanga and Sarah Maldoror’

38 J. Gugler, ‘African Writing Projected onto the Screen: Sambizanga, Xala and Kongi’s Harvest’, p.83

39 S. Swanson, ‘Reel Women: Episode 2: Sambizanga’, 4mins 32secs

40 N. F. Ukadike, ‘Reclaiming Images of Women in Films from Africa and the Black Diaspora’, pp.110-111

41 from 1 hour 27 minutes 38 seconds to 1 hour 29 minutes and 16 seconds

42 N. F. Ukadike, ‘Reclaiming Images of Women in Films from Africa and the Black Diaspora’, p.111

43 M. Dembrow, ‘Sambizanga and Sarah Maldoror’

44C. Zetkin, ‘Lenin on the Women’s Question’

45 F. Pfaff, Twenty-five Black African Filmmakers: A Critical Study with Filmography and Bio-Bibliography, p.210

46 F. Pfaff, Twenty-five Black African Filmmakers: A Critical Study with Filmography and Bio-Bibliography, p.207

47 For further reading on the MPLA’s goals of building alliances with other African nationalist movements and obtaining external assistance see: J. Marcum, The Angolan Revolution, Vol. II, Exile Politics and Guerrilla Warfare (1962-1976),pp.10-27

48 M. Webber, ‘Angola: Continuity and Change’, Marxism’s Retreat from Africa, pp.127-128

49 F. A. Guimarães, The Origins of the Angolan Civil War: Foreign Intervention and Domestic Political Conflict, p.45

50 J. Marcum, The Angolan Revolution, Vol. I, The Anatomy of an Explosion (1950-1962), p.29

51 F. A. Guimarães, The Origins of the Angolan Civil War: Foreign Intervention and Domestic Political Conflict, p.39

52 For further reading on the role of the PCA in the foundation of the MPLA see: J. Marcum, The Angolan Revolution, Vol. I, The Anatomy of an Explosion (1950-1962), pp.28-30

53 F. A. Guimarães, The Origins of the Angolan Civil War: Foreign Intervention and Domestic Political Conflict, p.39

54 M. Webber, ‘Angola: Continuity and Change’. In Marxism’s Retreat from Africa, pp.141-142

55 M. Webber, ‘Angola: Continuity and Change’. In Marxism’s Retreat from Africa, p.128

56 See ‘Survey of Criticism’ in F. Pfaff, Twenty-five Black African Filmmakers: A Critical Study with Filmography and Bio-Bibliography, pp. 212-213

57 M. Dembrow, ‘Sambizanga and Sarah Maldoror’

58 J. Gugler, ‘African Writing Projected onto the Screen: Sambizanga, Xala and Kongi’s Harvest’, p.80

59 M. Moorman, ‘Of Westerns, Women, and War: Re-Situating Angolan Cinema and the Nation’, p.111

60 M. Dembrow, ‘Sambizanga and Sarah Maldoror’

61 D. P. Noth, ‘Film Gets Grip on a Revolution’, The Milwaukee Journal

62 L. Krohn, ‘On Film Political, Poetic ‘Sambizanga’’

63 For further reading on Battleship Potemkin see: R. Taylor, The Battleship Potemkin: The Film Companion

64 B. L. Cummings, ‘African Cinema and Soviet Filmmaking’

65 T. Mulcaire, ‘February 4’

66 D. P. Noth, ‘Film Gets Grip on a Revolution’, The Milwaukee Journal

67 P. Abbott and M. Rodrigues, Modern African Wars 2: Angola and Mozambique 1961-74, pp.8-10

68 P. Chabal, A History of Postcolonial Lusophone Africa, p.144

69 N. Macqueen, The Decolonization of Portuguese Africa: Metropolitan Revolution and the Dissolution of Empire, pp.28-36

70 P. Abbott and M. Rodrigues, Modern African Wars 2: Angola and Mozambique 1961-74, pp.8-10

71 For further reading on the MPLA’s Eastern Front see: I. Brinkman, ‘War, Witches and Traitors: Cases from the MPLA’s Eastern Front in Angola (1966-1975)

72 P. Chabal and N. Vidal, Angola: The Weight of History, p.83

73 M. Kerbel, ‘Angola: Brutality & betrayal’

74 D. Birmingham, Frontline Nationalism in Angola & Mozambique, p.36

75 D. Birmingham, Frontline Nationalism in Angola & Mozambique, p.36

76 P. Chabal and N. Vidal, Angola: The Weight of History, p.74

77 D. Birmingham, Frontline Nationalism in Angola & Mozambique, p.36

78 D. Birmingham, Frontline Nationalism in Angola & Mozambique, p.36

79 M. Kerbel, ‘Angola: Brutality & betrayal’

80 F. A. Guimarães, The Origins of the Angolan Civil War: Foreign Intervention and Domestic Political Conflict, p.45