Dance Body Protest, Somatic practices against racism

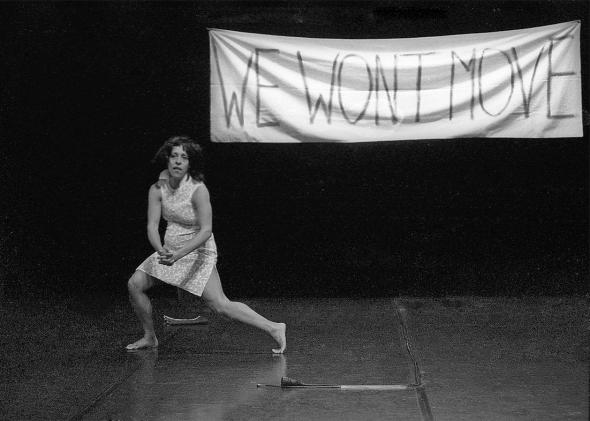

When Sarah Bergh and Sandra Chatterjee asked me to write some thoughts about Dance, Body and Protest, one of the first thing, that I remembered was one of my dance productions called Permanent Prints (1999), premiered at Kampnagel Hamburg. This production was a triptych, constituted of three different choreographic works, one of those pieces, we called it Duett, casted by myself and Cristina Moura. While the audience rushed into the theater space we would be on stage, sitting at a chair, looking at the audience, with an empty look, the set-design was a self-written banner hanging above our heads, on which we could read the statement „We won’t move“. My main concern was to bring up themes for reflection such as multicultural identities (today I would have used the terminology ‚body of cultures‘), gender, racism, sexism, and social political conflicts.

Dancer and choreographer Angela Guerreiro has never performed unclothed in her solos or pieces; instead, she has addressed multicultural identity and gender issues, racism, sexism and (social) political conflicts in her work.1

Before the premiere, I was asked if I would be interested of having a pre-premiere of Permanent Prints to a group of three hundred gynecologists because they were interested in seeing a ‚ballet‘ piece. That proposal sounded totally out of context, due to the fact that I was not creating ballet pieces, but still I said yes. The Duett was the second part of the triptych, I was seven months pregnant, and after 15 minutes, we saw how the audience started to leave the venue. After that experience, I had the chance to talk to one of the gynecologists who came to see the performance, he told me, „I want to tell you that I loved your performance and I would like to apologize for my colleagues because gynecologists are so conservative.“. If I look back, we were presenting two black woman, dancers, one of them pregnant and performing movement scores out of the conventional approach, the ballet had changed color and offered something that was not part of their bodymind concept. The Duett, was dealing with prejudices and clichés around the blackbody, the dancers body, bodies with a complexion and a muscle tonus which under their perception differs from the ‚institutionalized’ body of the classical ballerina.

Guerreiro’s identity survey was based on a very personal examination of the dancers’ respective cultural backgrounds and their ethnic, sexual and gender-specific characteristics. Thus, the solo of the Welshman Marc Rees is much about (homo-)sexuality, Guerreiro himself dances the duet with the Brazilian Cristina Moura. Both are dark-skinned, so their dance also calls into question the identity-creating potential of skin colour. Guerreiro describes her attitude as artistic director as simply showing a “private performance” by the individual dancers was not her goal. Rather, she is more interested in looking for something worthy of generalization beyond the private access.2

Angela Guerreiro in Duett, Permanent Prints, Kampnagel Hamburg 1999. © Photos Wolfgang Unger

Angela Guerreiro in Duett, Permanent Prints, Kampnagel Hamburg 1999. © Photos Wolfgang Unger

But the reason why, I decided to bring up this piece as a departure point to write this text is because that same written statement „We won’t move“, from 1999, can be brought up again 21 years later. „We won’t move“ was a manifesto, a protest displaced in time, a proposal that had no counterparts, to talk about multiculturalism, colonized bodymind, white supremacy, gender, and racism, which seemed to ‚early’ within the context of the European dance field. How could we start discussing about the above if there are no resources to depart from, in one review we could read:

Guerreiro and Moura move to the second picture with a chair on a square meter of green. A duet of demarcation and synchronous agreement begins. A clownish double in which the duo borrows arms and legs on either side until the rest of each individual will finally unloads itself in wild insults. In a my-and-your quarrel butts and breasts pose for the attention of the audience. “This is not an erotic show, this is a work-in-progress”, Guerreiro announces with ironic boldness. But in the end, even this idea is no more than one of many that can boast neither inventive pride nor radicalism. For the fact that dancers chat out of their children’s rooms, install “We won’t move” manifestos, (…).3

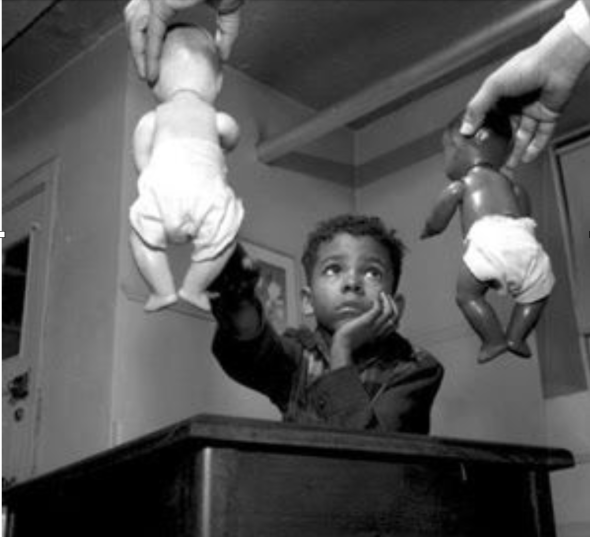

Indeed, we went back in our memories‚ our childhood, chatting out of our children’s room, when we start to become what we are, when memories act throughout our nervous system, our brain creating synapses, our muscles and bones moving and acting in an environment that have an impact in what we are now. It is, in a child’s room - in children’s books, songs, toys, fashion magazines, advertisements, on TV, at home, at school, and as a dancer attending ballet classes - when we recognize that we black people are considered different. Psychological experiments4, have been done in order to analyze this social phenomena, and if a black child is confronted with a black and a white doll there is still the preference to pick up the white doll and when asked why, the answer is, because the white doll is pretty, it has beautiful hair, and white skin, whereas the black doll is described as bad, mean and dirty.

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Harlem, Nova Iorque, 1947 © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Harlem, Nova Iorque, 1947 © The Gordon Parks Foundation

From three to six years old, I spend a great time of the day in a hairdresser, with my mother who was an aestheticist. I loved hair, and to comb the hairdresser clients’ hair was an immense pleasure, because they had the hair that I longed for. My mother, a white Portuguese woman, had no idea what to do with my hair, so every time I had a big Afro, which I adored, she just cut it short, no special hair conditioners, masks, hairdos, nothing, I just remember, to ask her not to cut it and unheard, I cried every time she did it. For me, it was like cutting off my special powers, because deep inside, I knew that my Afro was something special, something that, only I possessed.

My wish to become a dancer started when I was around 6 years old. Back in the years, Portuguese TV would show Opera and Ballet, on Sunday’s, the Matinee, and with that my dream began, I wanted to become a ballerina, to be lifted by a male dancer, hands on my waist with me handling a grand jeté. With ten years old, I started taking ballet classes, and those became my refugee, there I could be the dancer that I aspired, never questioning about my brilliant future career. Only, later when I had to wear make up, for the year school show, I noticed that there was no make up that could be applied to my complexion, all products available where made for a white skin complexion, at that time to have darker products available on the market was not to be considered. Today, looking at a photo with me wearing my ballerina straight hair and my skin covered by a lighter complexion make up, gives me the physical sensation of a totally alienated body, because I was aspiring a role, for which Portuguese society wasn’t prepared for.

I grew with statements such as „I had it in my blood“, an attempt to justify my virtuosity and my dance skills and I thought, ‚what do they mean with that? What does that mean that I have it in my blood? Do my white dance friends also have it in their blood? I never heard that being said to them. Nowadays, reflecting about those particular moments, these ‚micro-aggressions‘ and clichés, kept accumulating throughout my whole life. Once a friend told me, „You are not like them, you are different!“, but different from what or from whom? Different from the ‚other‘ black africans who would spend their time at Baixa do Rossio5, due to the Colonial war? But if I am also black, on what concept does such statement relies on? I was an alienated Afrodescendent, black Portuguese, young woman, colonized by Portuguese society and by my family, who was white. I talked without any accent, I had ‚manners‘, and I managed to enter the Superior Dance School Lisbon, which gave me recognition among the Portuguese artists and the art scene. Later on, I realized that, I was the representation of a black colonized bodymind person, not aware that I was accepted because I was ‚able’ to integrate Portuguese society.

As a black dancer and choreographer working in Germany since 1994, to put up a banner that literally expresses the refusal to ‚move’, to move the exotic body, the black body, was an utterly stand point against stereotypical perceptions of black bodies. That banner represented a silent scream against the constant perception of us, black bodies, as the exotic, therefore we stoped, a visceral refusal, the black body stoped as a way to give the audience a momento to think about what they were about to see.

Using a somatic approach, this banner was a protest, to the experienced daily micro-aggressions‚ „our stomach get’s stuck and I freeze“, a gut brain reaction due to the enervation of our vagal nerve6, our gut brain which is wired with neurons, information is sent to the brain area called the broca area responsible for speech, end response is that our ability to speak is blocked. Our somatic experiences are felt through our body, our peripheral nervous system (PNS) sensing the danger while our heart literally shrinks because of fear, of waiting longer in line at the passport cue, and each time, we think that something bad will happen. It is a lot to ask to our central nervous system (CNS), always holding back, or bearing an overly pride in order to get through life without major accidents. This are deep soul wounds that will only find peace if we accept healing as a process to get over mutual trauma.

Somatic approaches are a variety of methods that can provide healing, the same way a dancer ‚needs’ to find ways to go beyond the virtuosity, the mechanics, the mere execution of the body and the ‚dance technique‘, and instead find the knowledge about the felt-sense, the inner self, and the bodymind relationship, the same way all ‚bodies of cultures’ need to find strategies for healing the deep wounds racialization has left behind, incrusted in our daily lives, ‚trauma‘ that has been transmitted genetically through generations, it is in our cells, in our organisms, in our DNA, so that interrelationships of ‚bodies of cultures’ can be overcome if we approach it somatically. And I believe that the whole world needs to make an effort to overcome the social construct of racism. To understand that a structural racism still predominates in our society, the white supremacy, build in slavery, the killing, and applied brutality of people, who were not even considered as people but as animals, and as such did not have the same opportunities and living conditions as the white European settler. This leaves, centuries after centuries, traces of trauma, deep in our bodies.

“All of these practices foster resilience in our bodies and plasticity in our brains. We’ll use these practices to recognize the trauma in our own bodies; to touch it, heal it, and grow out of it; and to create more room for growth in our nervous systems.”

Resmaa Menekem

The same way, racism as been transmitted from generations to generations, change can only happen if individuals start to accept that change is essential and necessary and it starts by changing how the brainbody as been wired, even before the stage of a fetus, the moment the sperm enters the egg, DNA is being carried, and if this carries trauma then, that will be transmitted. And if my parents, my whole family defends and believes in the white supremacy this is what a child will learn, hearing parents expressing their prejudice against other people and this is what the nervous system memorizes. Here, I postulate, that I believe that peace and healing is only possible by changing our nervous system, with somatic activism, love, protest and the moving body always looking for the change in our soul.

- 1. Interview at Newspaper Hamburger Abendblatt, „Erleben statt verstehen“, Klaus Witzeling, 21.07.07. Quote translated 2 in English from original review.

- 2. Review, „Körperliche Ausprägung der Persönlichkeit“, Britta Peters, taz.de, 28.1.1999. Quote translated in English.

- 3. „Schlagbaum des Ich“, von Birgit Glombitza, taz.de, 1.02.1999. Quote translated in English from original review.

- 4. https://www.naacpldf.org/ldf-celebrates-60th-anniversary-brown-v-board-e...

- 5. With the colonial war may of the colones and africans from the colonies came to Portugal afraid of the war. But there 6 was no place for them in the Portuguese society, no work, no status. And many would just spend their time around Baixa do Rossio.

- 6. “Polyvagal theory“, Stephan Porges (1994). Neuroscientists have found that the vagus nerve is the main connection 7 between the brain and gastrointestinal tract and sends information about the state of the inner organs to the brain.