Do We Ask Too Much of Black Heroes?

Every year for a month, we celebrate the heroes of Black history. But these stories can obscure how change happens and who gets left behind.

In the early 20th century, before Negro History Week had turned into Black History Month, African-American teachers and children in schools throughout the segregated South would paste images of celebrated figures of Black history on the walls of their schools. It was a public affirmation that greatness existed among their people despite oppression. As a woman born post desegregation, in 1972, I remember the photocopied programs featuring a list of names to celebrate: Sojourner Truth, W.E.B. DuBois, Daniel Hale Williams, with facts to go along with each. Even then, I knew these models of aspiration were meant to guard me against any feelings of inferiority that might come from not seeing my story in textbooks or on screens.

Though the world has changed a great deal over the past century, celebrating heroes remains an important and familiar part of the Black History Month ritual. It is consistent with the way Americans celebrate history. As the historian Benedict Anderson notes in “Imagined Communities,” his examination of the rise of nationalism, in a national imagination the solitary hero is possessed of qualities and abilities that exceed what we expect of a human being and he (and it is usually a he) invariably succeeds. In the history of the United States, dominating the landscape and vanquishing all opponents (think George Washington and Davy Crockett) are classic hero’s traits. The hero becomes a proxy for the nation.

Black historic and political figures have been rendered as vanquishing heroes as well. Noble, brave and transcendent, they have remarkable stories. We tremble in awe before the recounting of Frederick Douglass escaping from slavery and Ida B. Wells narrowly evading the Klan in Memphis, saving her own life — then, through her investigative journalism into the practice of lynching, saving the lives of countless others. Martin Luther King Jr., who survived threats, bombs and jail cells before falling to an assassin’s bullets, has been rendered as the ultimate hero. His depiction is messianic. And though he was a key member of a vast and complex movement, he is often presented as singular. This is the way we tell history in the American public sphere.

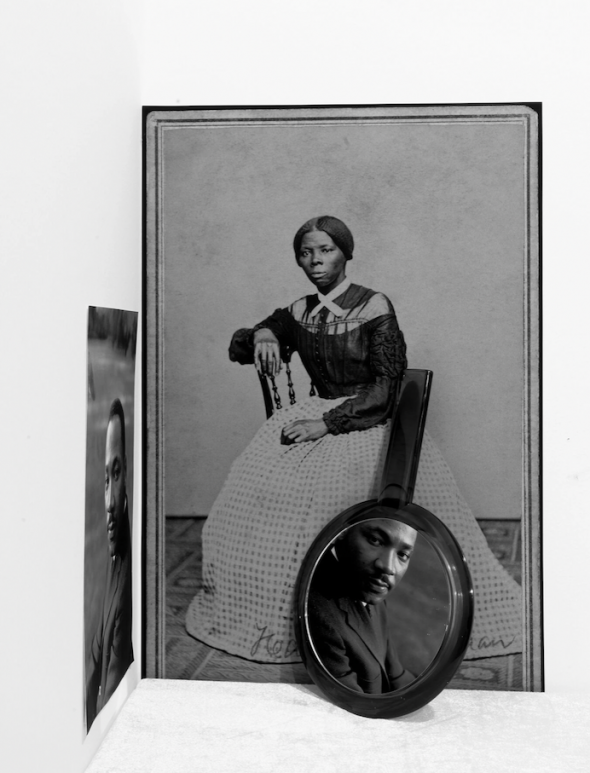

Photo Illustration by Aaron R. Turner for The New York Times

Photo Illustration by Aaron R. Turner for The New York Times

The Black American hero is necessarily more complicated than the mainstream “Great American heroes.” Both American and Black in a racially oppressive nation, he is a figure of double consciousness, often put to cross purposes. His greatness is trumpeted in order to reject the concept of Black inferiority and to assert belonging in the nation — a sign of legitimacy. “I, too, sing America,” he sings, as Langston Hughes once put it.

Or the hero might instead be a salvific figure, someone like Malcolm X or Huey P. Newton, who rejects the racist nation. See, for example, the embrace of Marcus Garvey, Garveyism and the Back-to-Africa movement in the early 20th century. Another type of Black hero is one who survives untold brutalities and lives to tell the tale, indicting white supremacy by his very existence.

Heroes, as historians and activists have noted for generations, are often made mythic in ways that are troubling. Social change is never wrought by individuals. Movement is a collective endeavor and the romantic ideal of the hero obscures that truth. Recent social movements like the Movement for Black Lives have been deliberate about describing themselves as leaderless or “leader-full,” in order to emphasize the importance of collective organizing while rejecting the model of the charismatic male leader. “We’re not following an individual, right? This is a leader-full movement,” Patrisse Cullors, a co-founder of the Black Lives Matter Global Network told NPR in 2015. “There [are] groups on the ground that have been doing this work, and I think we stand on the shoulders of those folks.”

These organizers look to the tradition of the Civil Rights movement as inspiration, such as the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, which oriented itself toward participatory democratic models, rather than the model of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which was organized in ways consistent with the Protestant Church. They have taken a lesson from the words of Ella Baker, the often-overlooked architect of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee: “Strong people don’t need strong leaders.”

The decision to choose leaderless or leader-full models is a refutation of the ideal of the traditional hero: martial, dominant and authoritarian in style, if not substance. It also recognizes the ways in which so many important figures have been excluded from being cast as heroes because they don’t fit the standard image, whether because of queerness, gender nonconformity, femininity, or mental or physical disability. The practice of overlooking these heroic people is ironic, given that navigating disadvantage often requires heroic labors. And although a few such outsiders make it into the annals, generally it is only if they are seen as “transcending” their very human qualities.

The traditionally constrained ideal of the Black hero is a challenge both within Black communities and in the society at large. These lauded individuals are anointed as proxies for all Black people and interpreters of Black thought — which flattens the widely divergent ideas among Black people about the political economy, social values, theology, racism, law and so forth. Groundbreaking figures like Colin Powell, Condoleezza Rice, President Barack Obama and Vice President Kamala Harris are subject to intense political debate, both within Black communities and without, over their ideologies, their roles in American policy and their relationship to communities of color even as we recognize the significance of being a trailblazing “first” of such consequence. No one person can tell the whole story, no matter how heroic that person might be.

That said, heroes remain. They resonate with people for good reason. Human beings organize knowledge through storytelling. We create ourselves in light of the stories we hear and tell. Having stories that give us courage and inspiration are always necessary but especially so when we face injustice. In trying times — and we are mightily tried — we need inspiration. Rather than an absolute rejection of the idea of the hero, we would do better to tell fuller and truer stories about those we place in those ranks, to deepen our understandings of them as fallible human beings. And we must include critically important people who are often left off the rolls.

The photographer Aaron R. Turner created these images for the New York Times’ 'Black History, Continued' project, in the style of his series, 'Black Alchemy,' which examines images of Black historical figures. 'I’m always trying to understand what black heroes meant to history and what we can learn from them now,' he said. 'I grew up in Arkansas and Martin Luther King was everywhere. King is rightfully remembered as a martyr but I feel sometimes we have to take a step back to see him as a man.' The figures in these images include Ella Baker, Martin Luther King Jr., Colin Powell, Harriet Tubman and Ida B. Wells Photo Illustration by Aaron R. Turner for The New York Times

The photographer Aaron R. Turner created these images for the New York Times’ 'Black History, Continued' project, in the style of his series, 'Black Alchemy,' which examines images of Black historical figures. 'I’m always trying to understand what black heroes meant to history and what we can learn from them now,' he said. 'I grew up in Arkansas and Martin Luther King was everywhere. King is rightfully remembered as a martyr but I feel sometimes we have to take a step back to see him as a man.' The figures in these images include Ella Baker, Martin Luther King Jr., Colin Powell, Harriet Tubman and Ida B. Wells Photo Illustration by Aaron R. Turner for The New York Times

Ella Baker stands as a heroic figure and a model for how to organize using a deeply democratic approach. Fannie Lou Hamer, a sharecropper who by many accounts was the moral center of the struggle in the Mississippi Delta for voting and economic rights, and who was physically disabled after facing violent retaliation for her organizing work, is not a household name — yet I have listened to Civil Rights organizers describing the emotional fortitude that came from hearing her sing, a woman beaten and bloodied near to death who nevertheless remained a soldier for freedom. Only recently has there been a revival of public recognition that Bayard Rustin, an openly gay Black man, was the architect of the March on Washington. And as young organizers have defined their own politics, people like trans-liberation organizer Marsha P. Johnson, have become heroes of our time.

However, even as we expand the pantheon of who counts as heroes, the heroic figure remains a juggernaut. As we freeze them on an altar of adoration, we run the risk of losing our critical perspective regarding who they were or are as full, complex human beings. In the world of social media and an information age with a 24-hour news cycle, heroes rise and fall in spectacular fashion on a daily basis.

In the end, perhaps we will find it necessary to refuse rendering any individuals as heroes uncritically and instead settle on what we can agree about: There is an undeniable heroism in refusing and transcending the narrow boxes that racism creates and the barriers it erects. We can acknowledge human fallibility and the sociological landscape out of which acts of heroism emerge. Heroes fail, and they succeed, and sometimes they fall short of our hopes. Perhaps they betray them. Our hearts leap when they exceed them. The valleys as well as the heights of anyone’s story must be deliberately attended to, including the stories of our heroic figures. Rather than serving as empty vessels into which we pour our fantasies, these figures can be taken on their own terms, including their full humanity.

Article originally published by The New York Times in 29/01/2021