“Luso-Tropicalism” and Portuguese Late Colonialism

This article presents and analyzes how, during the years following World War II, the Portuguese “Estado Novo”[i] used Luso-tropicalismo, a “quasi theory” about the relationship between Portugal and the tropics [ii developed by the Brazilian social scientist Gilberto Freyre (Recife, 1900-1987). An «archaeology» of Luso-tropicalismo sets its roots in the text The Masters and the Slaves (“Casa-Grande & Senzala”, 1933), considered one of the “books that invented Brazil” (Cardoso 1993). Later, other traces are made evident in the collection Conferências na Europa (1938) and its reviewed version O mundo que o português criou (The world created by the Portuguese,1940), about all the spaces under Portuguese colonization. This new formulation is officially outlined in the conferences “Uma cultura moderna: a luso-tropical” (A modern culture: luso-tropical, Goa, November 1951); and “Em torno de um novo conceito de tropicalismo” (On a new concept of tropicalism, Coimbra, January 1952), which were integrated in the work Um brasileiro em terras portuguesas (A Brazilian man in Portuguese lands, 1953). Integração portuguesa nos trópicos (Portuguese integration in the tropics, 1958) and O luso e o trópico (The Portuguese and the Tropics, 1961), all of which established the theory and contributed to its dissemination. Briefly, Luso-tropicalismo proposes that the Portuguese have a special ability to adapt to the tropics, not by political or economic interests but due to an innate and creative empathy. The aptitude of the Portuguese to form relationships with tropical lands and peoples and their intrinsic plasticity was supposedly the result of their own hybrid ethnic origin, their “bi-continentality” and their extensive contact with the moors and the Jews in the Iberian Peninsula during the first centuries of nationhood, which was manifested primarily through miscegenation and cultural interpenetration.

The Portuguese Estado Novo and luso-tropicalismo

In Portugal, and until the end of World War II, Gilberto Freyre’s thought was only well-received in the cultural milieu (vd. Castelo 1998: 69 84). Political power wobbled between implied rejection and open criticism.

Once the occupation of the colonial territories was concluded, the Portuguese state focused on asserting its empire, expanding the colonial administrative and fiscal machine and submitting the indigenous peoples, looked upon as savages, to the superior values of a supposedly Portuguese race (cf. Alexandre 1979: 7). In addition, among the myths concerning the foundation of nationality was the «Christian reconquest», emphasized as a heroic deed by fearless European soldiers, which was not in tune with the importance that Freyre gave to the Arabic and African roots in the formation of the Portuguese national character.

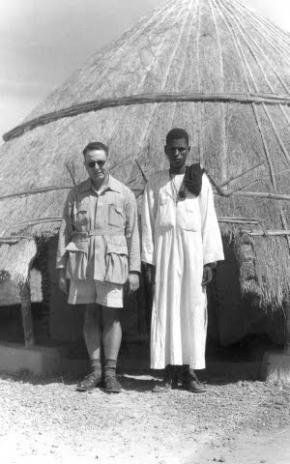

Gilberto Freyre with a shepherd in the Namibia Desert, 1952.

Gilberto Freyre with a shepherd in the Namibia Desert, 1952.

The colonial politics of the Estado Novo during the 1930’s - 1940’s was still distant from Gilberto Freire’s theory. Armindo Monteiro, Minister of the Colonies between 1931 and 1935, and the main ideologist of the «imperial mystique», was an adept of «social Darwinism». He did not believe in the possibility of a harmonious, brotherly and equal relationship between white and black people. He saw Portugal as having a “historical duty” to civilize the “inferior races” under dominance. It was about protecting the “indigenous”, converting them to Christianity, educating them through (and for) work, and morally, intellectually and materially elevating them. The rigid opposition between “civilized” and “primitive” carried the denial of other values, making impossible the perspective of cultural reciprocity. Moreover, the model of economic development in the colonies was based on the mere exploitation of natural resources and African labor, through forced work and mandatory cultural traits to the benefit of the parent state and the European colonists.

The main reason for disagreement in regards to Gilberto Freire’s theory was related to the importance that he gave to the question of miscegenation. During a top meeting of Salazar’s single party system – the National Union –, there were doubts as to the scientific value of Casa-grande & senzala, precisely for the emphasis placed on racial mixing (Ferreira 1944: 41). Making reference to the work of physical anthropologists such as the Portuguese Germano Correia and Mendes Correia and the French René Martial, Vicente Ferreira asserted the negative effects caused by cross breeding: “degenerations of the psychic character and eventually also of the somatic character” (Idem: 39). His picture of mestizos, mulattos and creoles was charged with prejudice and was extremely negative; he described them as “impulsive, indolent, and usually lacking in intelligence, docility and morals” (Idem: 40). With the purpose of preventing miscegenation and even socialization between whites and blacks in the areas of ethnic colonization, as well as economic competition between workers of both races, he proposed the establishment and rigorous enforcement of racial segregation policies in white settler regions, which forbade, among other things, that Portuguese colonists used indigenous labor (Idem: 78).

It is important to emphasize that even Norton de Matos (former high-commissionaire of the Angolan Republic and candidate by the Portuguese democratic opposition – Oposição – in the presidential elections of 1949) had reservations in regards to Gilberto Freire’s thought, particularly in terms of miscegenation and cultural interpenetration. Although he rejected the idea of the hopeless inferiority of black people, he considered that miscegenation was only acceptable once the assimilation process of the “backward races” was concluded – a process, which would take centuries. While Europeans and Africans were not equal in civilizational terms, the Brazilian experience should not be repeated in the Portuguese colonies in Africa, in order to avoid the degeneration of the values of western civilization.

The only aspect in Gilberto Freire’s thought that deserved the unanimous applause of both the regime’s colonialists and the Oposição, in the 30’s and 40’s, was his confirmation of the special ability of the Portuguese for colonization. At least since the last quarter of the 19th century and in face of external pressures and attacks, the national political and ideological discourse implied the idea of a special adaptation of the Portuguese to the tropical climate, as well as a special relationship with the colonized indigenous peoples (Alexandre 2000: 393). History and anthropology confirmed the existence of those abilities, which distinguished the behavior of Portuguese colonialists in African lands from that of Northern European colonialists.

Orlando Ribeiro

Orlando Ribeiro

The end of World War II condemned the project of hegemony and racial purity of Nazi Germany and created an awareness that freedom and independence were not a privilege of European countries, but rather a universal goal. The United Nations charter, created in 1945, consecrated the principle of self-determination for all colonized peoples. The Universal Declaration of the Rights of Men (1948) established self-determination as a fundamental right, and the UN ascribed colonial powers with the obligation to prepare the territories under their administration for independence. It was in this context that the anticolonialist movement emerged and was consolidated, and the decolonial process began, first in Asia and then in Africa.

After 1945, Portugal, confronted with international pressures that favored self-determination in colonial territories, attempted to create arguments that legitimated the maintenance of the status quo in the Portuguese colonies. This process of legitimization of Portuguese colonialism demanded changes in legislation, a doctrinal reformulation and unprecedented measures of economic development in Angola and Mozambique.

In 1951, in the reform framework of the Portuguese political constitution, the president of government, António de Oliveira Salazar, presented a proposal to annul the Colonial Act, integrating it in the constitutional text with changes in terminology and other slight adjustments. According to the government, the assertion of national unity, in spite of the geographical dispersion of Portugal among several continents, was the first goal to be achieved. The expression «Portuguese Colonial Empire», was banned because of its negative connotations in the new international context. The term «colonies» was replaced by the “old” designation of «overseas provinces». In spite of the negative reactions made by some prosecutors to the Câmara Corporativa, including Armindo Monteiro, former Minister of the Colonies, the majority of the National Assembly supported and approved the proposal. In this new formulation, Portugal became a «pluricontinental nation», composed by European and overseas provinces, harmoniously integrated in the national, indivisible whole. Hiding behind a wording composition that denied its possession of colonies, the Estado Novo considered itself unaccountable to the international community in regards to what was happening within its borders. The tone around the issue of overseas policies was, from then on, one of «assimilation».

The logic of assimilation was not reflected in the policies regarding the indigenous. The Indigenous Statute, reviewed in 1954, continued to deny Portuguese citizenship to the majority of the population in Angola, Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau. The assimilated, meaning those who proved to be integrated in the way of life and the values of European civilization, were a small minority, because there had never been a desire to create an elite overseas by expanding the educational system to Africans. The old creole elites of the 19th century had long been removed from the political system by new arrivals of colonialists and by the administration itself.

Two months after the affirmation of national unity in the Constitution of the Portuguese Republic, Gilberto Freyre began a visit to “Portuguese lands”, by invitation of the Minister of Overseas, Sarmento Rodrigues. The objective of the trip was to get the Brazilian sociologist acquainted with the Portuguese overseas territories, so that he could observe it “with the eyes of a man of studies”, and later produce an insightful work about the realities he had witnessed. It was during this trip that the Brazilian sociologist used the expression «luso-tropical» for the first time, in reference to the way that the Portuguese adapted to the tropics. This was a useful theory to strengthen the idea of «Portuguese pluricontinental national unity» and of a settler program overseas. The Estado Novo appropriated some quotes from luso-tropicalismo in order to defend itself from the pressures of the international community, particularly the UN charter (Portugal entered the organization in 1955), but also to use it in propaganda campaigns abroad, in declarations proclaimed by high officials to the foreign press and in diplomatic circles (vd. Castelo 1998: 96-101). Internally, this was a moment of consensus around national integrity and continuity of the country’s historical mission around the world.

International Politics and Diplomacy

Confronted with article 73 of the United Nations Charter, the government in Lisbon denied the existence of «non-autonomous territories» under Portuguese jurisdiction. In its 1951-revised constitution, Portugal considered itself a united state scattered in four continents, and therefore not covered by the obligations that the above-mentioned article imposed. In response to the accusations issued by the U.N., the Portuguese delegation made three main political arguments. The geographical distance between the metropolitan provinces and the overseas provinces was irrelevant since geography was not a valid base from which to define a colony. Any part of the national territory was oriented by equality of rights and opportunities for all, independent of «race»; biological and cultural mixing was considered a source of progress and development. The overseas provinces were not economically and financially exploited in favor of metropolitan ones; in fact, in some overseas territories, economic growth was higher than in continental Portugal. Defending the Portuguese positioning on the matter during the fourth Commission of the U.N. General Assembly, which took place in November 8, 1961, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Franco Nogueira, was not shy to mention international renowned social scientists including the sociologist Gilberto Freyre (Nogueira 1961: 213).

Franco Nogueira, Minister of Foreign Affairs (1961-69) In its official discourse, Portugal was constituted by a multiracial community, composed by geographically distant territorial parts, inhabited by populations of various ethnic origins, united by the same sentiment and culture. As shown by Freyre’s supposedly unsuspected studies, power as exercised in the Portuguese «overseas provinces» was not of a colonial nature like in territories under the rule of other countries.

Franco Nogueira, Minister of Foreign Affairs (1961-69) In its official discourse, Portugal was constituted by a multiracial community, composed by geographically distant territorial parts, inhabited by populations of various ethnic origins, united by the same sentiment and culture. As shown by Freyre’s supposedly unsuspected studies, power as exercised in the Portuguese «overseas provinces» was not of a colonial nature like in territories under the rule of other countries.

In order to face the new international moment, inaugurated by the Bandung Conference, and strengthen the arguments of the Portuguese after Portugal joined the U.N., the Estado Novo’s strategy was to disseminate Gilberto Freyre’s ideas among the represented nations. The task implied a constant following of Freyre’s intellectual journey and the inclusion of two of his books in the «international diplomatic circles».

In the mid 1950’s, Portuguese diplomats began to receive straight forward instructions to follow and communicate to the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, any information about the bibliographic production, the interviews and the academic activity of the Brazilian sociologist, as well as any news published about him by the international press. The Ministry’s Historic-Diplomatic Archives holds a great number of documents that demonstrate such diligent monitoring, from books, to conference papers, interviews and articles by (or about) Gilberto Freyre, published in magazines and newspapers from Brazil, the United States, England, France, South America and other places[iii].

In early 1959, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs began to distribute to Portuguese embassies, legations, consulates and delegations, Gilberto Freyre’s book Portuguese Integration in the Tropics published by the Political and Social Studies Center of the Overseas Research Commission in the previous year. Accompanying it, the following memo:

“It is an honor to send you separately, [x] samples of a publication by the overseas Ministry on the topic of Portuguese Integration in the Tropics.

As your Mission will notice this is a valuable study, in Portuguese and English, by the distinguished Brazilian professor, academic and historian Gilberto Freyre, which emphasizes some of the most notable aspects of Portuguese expansion in terms of its relationship with different peoples and races.

The use of the above mentioned study appears to be beneficial, so it would be advantageous to forward it to the entities that might take an interest in it”.[iv]

Recognizing the work’s political value, as well as its potential for argument and propaganda in favor of the Portuguese position, a significant number of Portuguese missions requested more volumes from the Ministry.

A few years later, the French translation of the collection The Portuguese and the Tropics (1961) was also distributed among Portuguese missions abroad. Artur Moreira de Sá, general-secretary of the International Congress for the History of the Discoveries, stated in an official document sent to the general-director of Political and Consular Affairs at the Ministry:

“As the distribution of the French edition of Gilberto Freyre’s book The Portuguese and the Tropics is now in place, and since there is a great interest in promoting it among the U.N.’s foreign representatives, the diplomatic representations in Lisbon, the Portuguese embassies and consulates, and other entities you may find relevant, I request from the Presidency of the Counsel that 2.000 copies are sent to the Ministry.”[v]

Thus, it appears that from the mid 1950’s on there was a systematic effort from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to indoctrinate Portuguese diplomats in the theory of Luso-Tropicalismo. The objective was to provide them with the (supposedly) scientific arguments, grounded in history, sociology and anthropology that could legitimate the presence of Portugal in Africa, India, Macau and Timor. They were also given the task of promoting the Brazilian sociologist’s ideas among the delegates of countries with representation at the U.N. The need to promote and assert Luso-Tropicalismo at the United Nations became stronger after the beginning of the colonial war in Angola and the occupation of Goa, Daman and Diu by the Indian Union. It seems that Luso-Tropicalismo had an impact abroad[vi], at least until the beginning of the armed struggle for independence in Angola. After that, it became increasingly difficult for Portuguese diplomacy to hold the anachronistic position of the government in Lisbon.

Propaganda and Media

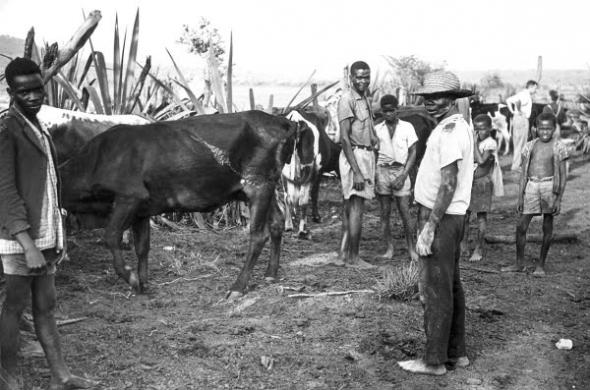

Orlando Ribeiro and Talibé, Bissau, 1947The dissemination of the Portuguese position was not restricted to international political forums and diplomatic circles. National propaganda campaigns abroad praised Portuguese contributions for brotherhood among peoples and for the integration of different races and cultures in the same nation. The country’s participation in the Universal and International Exposition at Brussels in 1958 is a good example. The work published by the Exposition’s, evocatively entitled Portugal: Oito séculos de história ao serviço da valorização do homem e da aproximação dos povos (Portugal: Eight Centuries of History at the Service of the Appreciation of Men and the Convergence of People), includes many references to the Luso-Tropical doctrine. In the article “Um povo na terra” (One people in the land), geographer Orlando Ribeiro assures that “Portuguese is not […] a concept of race, but rather a «unity of sentiment and culture», that brought men of different origins together” (AAVV 1958: 38). By “calling local populations to participate in a common civilization”, Portugal was preventing “the awakening of false local nationalisms” (Idem: 39). Adriano Moreira frequently quoted Gilberto Freyre’s essay Integração portuguesa nos trópicos (Portuguese Integration in the tropics, unpublished at the time), in order to attempt to demonstrate that Portugal was responsible for “drafting the only humanism capable, to this day, of implementing human democracy in the world to where the West had expanded” (Idem: 305). In turn, Sarmento Rodrigues defended that “Portuguese national unity” formed and existed “by will of all men, with the goal of elevating all Portuguese people, free of intentions to exploit the economy, and other areas, for the sole profit of the original people” (Idem: 315). He also emphasized the Christian aspects of human relations, in the mist of the Portuguese nation, marked by cultural interpenetration and the absence of “prejudice against miscigenation” (Idem: 316).

Orlando Ribeiro and Talibé, Bissau, 1947The dissemination of the Portuguese position was not restricted to international political forums and diplomatic circles. National propaganda campaigns abroad praised Portuguese contributions for brotherhood among peoples and for the integration of different races and cultures in the same nation. The country’s participation in the Universal and International Exposition at Brussels in 1958 is a good example. The work published by the Exposition’s, evocatively entitled Portugal: Oito séculos de história ao serviço da valorização do homem e da aproximação dos povos (Portugal: Eight Centuries of History at the Service of the Appreciation of Men and the Convergence of People), includes many references to the Luso-Tropical doctrine. In the article “Um povo na terra” (One people in the land), geographer Orlando Ribeiro assures that “Portuguese is not […] a concept of race, but rather a «unity of sentiment and culture», that brought men of different origins together” (AAVV 1958: 38). By “calling local populations to participate in a common civilization”, Portugal was preventing “the awakening of false local nationalisms” (Idem: 39). Adriano Moreira frequently quoted Gilberto Freyre’s essay Integração portuguesa nos trópicos (Portuguese Integration in the tropics, unpublished at the time), in order to attempt to demonstrate that Portugal was responsible for “drafting the only humanism capable, to this day, of implementing human democracy in the world to where the West had expanded” (Idem: 305). In turn, Sarmento Rodrigues defended that “Portuguese national unity” formed and existed “by will of all men, with the goal of elevating all Portuguese people, free of intentions to exploit the economy, and other areas, for the sole profit of the original people” (Idem: 315). He also emphasized the Christian aspects of human relations, in the mist of the Portuguese nation, marked by cultural interpenetration and the absence of “prejudice against miscigenation” (Idem: 316).

During the 1960’s, in an effort to gain support and captivate international public opinion, Salazar gave several interviews to the foreign press, using arguments taken out of Luso-Tropicalism in order to justify Portuguese presence in Africa. In his declarations he constantly emphasized the “natural tendency [of the Portuguese] to make contact with other peoples, free of concepts of superiority or racial discrimination”[vii]. Using Freyre’s conclusion he explained that the Portuguese wouldn’t know how to position themselves differently in the world, “since it was in a kind of multiracial society that eight centuries ago we became a nation, at the end of many invasions originated in the East, the North and the South, that is, from Africa itself” (Ibidem). Questioned about the differences between Portuguese policies in its overseas provinces and those of other powers, he went back once more to the phrases employed by the theory of Luso-Tropicalismo: “we fundamentally differ from others, because we always tried to unite with the peoples we came into contact with, not only through political and economic ties, but mainly through cultural and human exchange, giving a little of our soul and taking what they could give us”[viii]. Not an apologist for miscegenation, he then emphasized that from the fusion of the Portuguese with the “discovered peoples” there resulted multiracial societies in Brazil, Goa and Cape Verde and that those examples of Portuguese creative ability were about to repeat themselves in Angola and Mozambique[ix].

Gilberto Freyre, Goa (Índia), 1952

Gilberto Freyre, Goa (Índia), 1952

Taking into account the regime’s dictatorial nature, it’s not strange that Estado Novo controlled, censored and manipulated information through media, abroad as at home. Conquering public opinion was a decisive element in the struggle for the survival of a «Portuguese pluricontinental nation». The press received specific instructions on how to approach news concerning the overseas territories. They were to avoid expressions that denoted the separation between the metropolis and the overseas provinces; Portugal had to be included in any mention of nations or Asian and African states; it was not even allowed to insinuate distinctions between races or attack Islamic, Hindu and Buddhist religions[x].

The Political Affairs department at the Overseas Ministry was responsible for daily commentary broadcasted throughout the empire by the National Radio concerning topics of national interest (the attack of the Indian Union on Goa, “terrorism” in Angola, anti-colonialism in the UN, the communist ‘threat’, the overseas settlement, the economic development in Angola, etc.), and presented Portugal as an ethnically and culturally heterogeneous nation, geographically dispersed by several continents. Gilberto Freyre (the author and/or his thought) is often evoked in such commentary. An example is the following comment about the Luso-Brazilian Community:

“What effectively defines Portugal, what makes us unique among other nations, is what has been termed as spirit of mission, that is; eagerness to take farther in space the concept of life one carries; not the desire of an economic empire or terrain, not even political domination – but the irresistible calling to communicate to others the Truth one possesses. […]

[…] Portugal is only whole if global – only then its physical life truly begins; Portugal will only reach its authentic projection onto the World when it overcomes the national plan – its heyday will come with the plenitude of the Luso-Brazilian community, with the maturity of the Luso-tropical complex. That is where we are headed today, that is why we work[xi]”.

In practical terms, the objective of these deeply propagandist comments was to build the ‘pedagogy’, the indoctrination of the Portuguese, about who they were (as a people), their mission in the world and how they should behave. Using a conference that was taking place in Lisbon, the National Radio broadcasted:

“[…] it is essential […] that we know what it means to be Portuguese and how such condition must be translated in the social-political realities and in the framework of human geography. Thus – because the question is not really at issue and all Portuguese, even unconsciously , felt the presence, in their souls, of the elements constituting that substantiation -there practically has not been, so far, a preoccupation to investigate such elements in a systematic manner and to search, through them, to elaborate such substantiation as a structured body.

And it was the aggression against us in Angola that violently called the attention of the Portuguese to the need of such investigation and such elaboration, not just as an intellectual exercise but as a practical and conscientious basis for action. Much surfaced on the matter – and it is impossible not to emphasize the studies of Gilberto Freyre and the fascinating book by Francisco Cunha Leão about «The Portuguese enigma» – it is fair to call attention to the conference occurring in Lisbon at the moment, organized by a group of young writers and thinkers about the general theme «What is the Portuguese ideal?»”.[xii]

A gouli with two women and his children, Goa, 1955.

A gouli with two women and his children, Goa, 1955.

In an attempt to go against accusations of racism and discrimination in the Portuguese colonies, as well as feelings of racial superiority that persisted among settlers, another comment states that the Portuguese are not white:

“Yes dear listeners! We are without a doubt, and above all, an Euro-African people. The descendants of those African captives – such practice was normal around the world including among African traditional societies – mixed with the Portuguese people of those days, and the livelihood of those genes, of the resulting elements of heredity, persists in the so-called metropolitan people to whom an incomprehensible geographical criteria denies them rights and affinity with Africa.

To those who are listening, rest assured that among the Portuguese there are no «whites» in the sense of differentiated ethnicity.”[xiii]

Academic and scientific milieu

Parallel to official discourse, luso-tropicalismo was well-received by experts from different areas of knowledge: Jorge Dias (anthropology), Orlando Ribeiro and Francisco José Tenreiro (geography), Adriano Moreira (political science), Mário Chicó (art history), Henrique de Barros (agronomy), Almerindo Lessa (human ecology); António Quadros (philosophy), etc. Adriano Moreira had a prominent role in this process, as a professor and director of the Higher Education Institute of Overse as Studies (Instituto Superior de Estudos Ultramarinos), which later became the Higher Education Institute for Social Sciences and Over seas Politics (Instituto Superior de Ciências Sociais e Política Ultramarina, an institution that trained officials for over seas duties); and as director of the Center for Political and Social Studies (CEPS) from the over seas Investigation Commission (JIU), attached to the above mentioned institute.

Adriano José Alves Moreira, Minister of Overseas (1961-62)

Adriano José Alves Moreira, Minister of Overseas (1961-62)

During the academic year of 1955-56, Adriano Moreira, as chair of a program in Overseas Politics, introduced the study of luso-tropicalismo during the second year of the degree of Overseas High Studies. The doctrine of Gilberto Freyre became systematically taught at a Portuguese university and inspired various theoretical and field works[xiv], monographies and dissertations. Many of those works would later be published by the Higher Education Institute of Overseas Studies (Instituto Superior de Estudos Ultramarinos), later the Higher Education Institute for Social Sciences and Overseas Politics (Instituto Superior de Ciências Sociais e Política Ultramarina) and by JIU’s CEPS, in the collection «Estudos de Ciências Políticas e Sociais» (Social and Political Sciences Studies).

The work developed by Adriano Moreira when he led the CEPS, created by decree number 15737, of February 18 1956, shows preoccupied reflections on luso-tropicalismo. The center aimed at “coordenating, estimulating and promoting the study of political and social phenomena verified in the communities formed in the overseas territories or related to them, observing and exposing in particular the foundations, characteristics and results of the actions developed by the Portuguese overseas” (Moreira 1956). Its activities were divided in three major areas: editing (namely through the collection «Estudos de Ciências Políticas e Sociais»); the organization of conferences; and the coordination of study groups to the overseas provinces.

The analysis of the works published in the collection makes way to the evaluation of the consequences of luso-tropicalismo in the field of social sciences where this connected with overseas issues. We find direct references to Freyre’s ideas (namely through citations of his work) and/or the inclusion of his books in the bibliographies of several of those studies (cf. Castelo 1998: 102-103).

One can also glimpse at the influence of the luso-tropical ideal in the initiatives that Adriano Moreira put forth when he headed Lisbon’s Geographical Society, including: the organization of two congresses by the Portuguese Communities around the world (1964 and 1967) and the creation of the International Academy for Portuguese Culture (Academia Internacional da Cultura Portuguesa, 1964).

The public adherence of prominent Portuguese academics to luso-tropicalismo hides, in some cases, a critical conscience face to what was in fact happening in the Portuguese colonies. Confidential reports show the enormous distance between the actual colonial action and the luso-tropical theory. In fact, Portuguese colonization, like others, rested on racial barriers, generated conflicts and promoted discrimination. Racial discrimination was primarily put in place by the judicial differentiation of the so-called indigenous (regulated by a specific statute). Corporal punishment, inflicted on workers and domestic servants by their bosses, and on «non civilized» Africans by administrative and police authorities (paddle beatings) and raids (to “capture” runaway indigenous who infringed contracts, tax evaders, independent workers or liquor producers) were in the forefront of explicit forms of racism. There were also more subtle ones, such as salary gaps and difficult access to jobs and social promotion. Among the causes of conflict and social malaise were forced recruitment (called chibalo in Mozambique), which provided colonials (companies, individuals and the administration) with cheap labor, shipment of commissioned workers to the plantations of São Tomé, mandatory cultures, land occupations, barter trade through the exploitation of indigenous people, tax collection and a lack of respect for gentile authorities.

Porto de Bissau, peanut shipment, 1947

Porto de Bissau, peanut shipment, 1947

After the mid 1950’s, warnings from a few scientists, directed to the navy, alerted to a change in the behavior of colonialists regarding the Portuguese “tradition”[xv]. However, in the face of practices that denied the model of peaceful socialization, miscegenation and interpenetration of cultures, it was considered that it was not the model that was detached from reality but rather the practices that were deviant from “Portuguese tradition”.

In the confidential report of JIU’s study group in Goa, in 1956, Orlando Ribeiro revealed clearlythe little influence of Portuguese culture, the lack of Portuguese language usage, the weakness of the Catholic Church, the meaningless role of miscegenation (Ribeiro 1999). During the same year, in the confidential report put together by anthropologist Jorge Dias, concerning the work of the study group on ethnic minorities in the Portuguese overseas territories (created by JIU’s CEPS)[xvi], it is clear that in Mozambique the miscegenated were treated like indigenous and the majority of colonials considered black people to be inferior. In Angola, it is noted a “satisfactory evolution” similar to that of Brazil, but also a repression of “unnecessary abuses” and the promotion of the indispensable economic and social development. In Guinee, the influence of Portuguese culture was practically nonexistent.

In 1959, Jorge Dias led a new study group on the ethnic minorities of the Portuguese overseas territories. The confidential report, sent to the president of the counsel, denounced once more the cases of racial segregation[xvii]. The comparison between racial relations at Tanganica and Mozambique revealed that while in the first the English had adopted policies of collaboration with the indigenous people, in the second the Portuguese mistreated Africans, even those who had been assimilated.

In a report by Jorge Dias concerning his participation in a meeting that took place in Frankfurt about the “political problems of the lives shared by blacks and whites in Africa”, the anthropologist confessed that his speech was well received “because the Portuguese traditional position was absolutely defensible when put forth in terms of historical and social evolution, as an aspect of the history of humanity that preceded the European capitalist expansion”[xviii]. He emphasized that such facts, the Portuguese social structure and the national character of the Portuguese originated “a type of colonization that as a process was entirely different from 19th century colonization” (Idem). However, he alerted to the fact that: “poor us if we discover that in reality we are grossly departing from a traditional conduct to take the path of brutal and merciless exploitation of indigenous people, forgetting the Christian humanity that defines us and gave us the reputation of exceptional colonizers” (Idem). He concluded that in the political arena, Portuguese sovereignty in the overseas territories depended on correcting the abuses and guiding the behavior of Portuguese colonialists in more humane Christian direction.

In the face of racial problems detected by various researcher, the counsel of JIU’s CEPS advised talking up measures to promote to public opinion, particularly the colonialists, racial tolerance, condemnation of exploitation and discrimination of black people, education, and social and economic promotion for the African populations.

Legislation and political action

In 1961, the Salazar regime faced a series of difficulties: the assault on the ship «Santa Maria», led by Henrique Galvão (January), the attempt to liberate prisoners from the Luanda jails (February), the massacres orchestrated by UPA (Union of the Peoples of Angola) in the north of Angola, the military coup led by General Botelho Moniz (March) and the occupation of Goa, Daman and Diu by the India Union (December). The government, with the incentive of the Overseas minister Adriano Moreira who took office in April 1961, was forced to enact a large group of measures that aimed at eliminating the most archaic forms of colonial exploitation (contract and mandatory cultures) and racial discrimination (the Indigenato laws). The cancellation of the Portuguese indigenous statute in the provinces of Guinea, Angola and Mozambique (law number 43893, of 6.9.1961) allowed Portuguese citizenship to all inhabitants in those territories. At the same time, it greatly stressed the formation of multiracial societies overseas, through increased European settlement.

A Portuguese settler family at Cela settlement (South Cuanza, Angola), 1960

A Portuguese settler family at Cela settlement (South Cuanza, Angola), 1960

For that purpose it was created a state board for Angola and another for Mozambique (law decree number 43895, of 6.9.1961), both high organs of public administration that were responsible in each of those overseas provinces for conducting and guiding all matters concerning the settling of the territory and for coordinating public and private initiatives of their interest. Aiming to promote the propagated multiracial integration, there was an effort to take in natives and Cape Verdeans in the new settlements, some of which were already mixed.

In the forward to the decree that created the state boards for the settlement of Angola and Mozambique, Adriano Moreira used arguments influenced by luso-tropicalismo and mentioned Gilberto Freyre.[xix] He explained that the settlement problems “were at the roots not only of the socio-economic valorization of territories and peoples, but also of their own rise and of the integration with foreign ethnic elements in the common nation, in that harmonious multiracial community which we have traditionally proposed and attempted to create”. Separately from the modes of settlement to implement, “at the base of its conception will always be the fulfillment of the ecumenical vocation of the Portuguese people, translated in the creation of pluriracial communities that are fully integrated and stable, an harmonious synthesis of various cultural values, and of which the fruitfulness in the formation of new and uniquely rich tropical civilizations, Brazil has been the most complete and eloquent example” (Diário do Governo, I série, n.º 207, p. 1129).

The “high priority” given to the European settlement of Portuguese Africa was seen as “an enormous and urgent” task, which could not be solely up to “mere individual inspiration”, but had to be fully taken by the state. Multiracial integration, “absolutely achieved through rejection of all mercenary attitudes”, justified intensive settlement with metropolitan elements, which “thereby establish their home and find their own sequel of the homeland”, incentives to the permanent settlement of “specialized workers of all levels and areas”, creation of mixed settlements, promotion of rural communities and, in general, hastened development of infrastructures and economies in the overseas territories (Portugal. Ministério do Ultramar 1961: 8-11).

On the 1st of February, 1962, decree number 44171 was finally enacted, opening the doors for the settlement of Portuguese citizens anywhere in the national territory (together with the creation of the «Portuguese Economic Area»). Until then, the Portuguese citizens who wished to migrate to the colonies had to obtain the so called «calling letter», proving that they had placement and means of subsistence. Obstacles created by the Estado Novo to the mass migration of metropolitan natives began being gradually lifted in the post World War II era. It was not until the 1950’s that the model for economic development and racial relations implemented in the colonies ceased to be framed by mere utilitarian concepts of exploitation of local human and natural resources, and began to contemplate the intensive European settlement of those territories and the improvement of the livelihood of Africans.

Azorian colonial settlement, Catofe (Cuanza Sul, Angola) 1960

Azorian colonial settlement, Catofe (Cuanza Sul, Angola) 1960

In the context of the wars for liberation of Angola, Guinea and Mozambique the colonial governments and the Armed Forces needed to develop a set of socio-political initiatives to gain the support of the peoples subjected to Portuguese colonialism and reduce the support for independence movements, as well as to ‘educate’ settlers in matters of racial tolerance and human rights. Among the general goals of the Psycho-Social Action was the promotion of understanding between people of different «races» and religions, “within the principles of humanity, justice and respect for traditional values, in constant assertion of the concept of luso-tropicalismo, that set us apart from other nations”[xx]. Under such spirit, there were various actions taken, from the promotion of sports (particularly, football matches), festivities, dancing events, film sessions, etc.

However, there are several accounts that such seductions of Africans were not understood and reproduced by other agents of colonial power nor by the majority of settlers (vd. Castelo 2007: 357-362). In 1972, a dispatch by the Minister of Overseas Silva Cunha, printed on a report by the Province Board of Psychological Action of the general government in Mozambique, which denounced frequent offences practiced against native populations, showed how apart equalitarian and harmonious social relations between Europeans and Africans really were:

“Viewed with concern, particularly in verifying that, in spite of insistant instructions and recommendations, there are still violences and ilegalities in the relations between authorities and individuals towards the native population in matters of work and property. The government of the province must make a serious effort to end inconvinient and illegal practices that contribute to facilitate subversive action.”[xxi]

Final comments

The Estado Novo, during the 1930’s and 1940’s ignored or rejected Gilberto Freyre’s thesis, due to the importance it gave to miscigenation, cultural interpenetration, Arab and African inheritance in the origins of Portuguese people and the societies they created through colonization. The ideas of the Brazilian thinker had to wait for the 1950’s to be well received by Salazar’s regime. At that time, the regime adopted a simplified and nationalistic version of luso-tropicalismo as official discourse to be used by propaganda and foreign politics. The change in attitude was connected to the international context of the post World War II era and the need for the Portuguese government to assert national unity in face of international preassures favoring the colonies’ self-determination. At the same time, luso-tropicalismo entered the academic and scientific milieu, particularly in the areas connected to the training of overseas administrative personnel and the so-called ‘scientific occupation’ of the colonies. With the beginning of the war in Angola, and the coming of Adriano Moreira to the Ministry of Overseas, a set of legal measures inspired by luso-tropicalismo was enacted. In the new context, there was an attempt to instil in the Portuguese the idea of the benignity of Portuguese colonization or, more euphemistically, of the “Portuguese way of being in the world”. Propaganda tirelessly took charge of that goal: it was urgent to shape the way of thinking to match the actions taken, particularly among settlers and agents of colonial power in the field. Since then, a simplified version of luso-tropicalismo took over national imagination contributing to consolidate the self-image in which the Portuguese see themselves at their best: a tolerant, brotherly, plastic people with a ecumenical vocation.

The work of Gilberto Freyre demonstrates his singular conception of time, merging past, present and future. Such conception shows us the ambiguities and contradictions when he speaks of the luso-tropical community. At times, he presents it as a past reality, dated from the 15th and 16th centuries, other times as a living, present reality, and other times even as future, destiny, idealization. It is mainly as a project that the idea of a luso-tropical community survived its author after the Portuguese empire ended. And it continues to this day in the Community of Portuguese Language Countries and in the more consensual political and ideological discourse about Portugal’s position in the world. The risk now is that it continues to be used as a rhetoric device from an acritical and fixed perspective. Yesterday to legitimate Portuguese colonialism; today, to perpetuate the myth of racial tolerance among the Portuguese, and even of a Portuguese nationalism that is inclusive and universal, in opposition to «bad» nationalisms, that are closed, ethnocentric and xenophobic.

Notes:

[i] Formally instituted in 1933, after the military coup of May 28, 1926, overthrew the 1st Republic (1910-1926), Estado Novo was a conservative, catholic and colonialist dictatorship. Its main figures were the presidents of the counsel, António de Oliveira Salazar (until 1968) and Marcelo Caetano (from 1968 to April 25th, 1974).

[ii] Peter Burke and Maria Lúcia Pallares-Burke refer to luso-tropicalismo as a “quasi-theory”, “perhaps the closest thing to a theory that Freyre ever enunciated” (Burke and Pallares-Burke 2006: 188-189). As for Adriano Moreira and José Carlos Venâncio, among others, they consider luso-tropicalismo a social theory (Moreira and Venâncio 2000). On turn, Miguel Vale de Almeida considersluso-tropicalismo a discourse (Almeida 2000: 183-184).

http://www.contramare.net/site/luso-tropicalism-and-portuguese-late-colonialism-part-2/

[iii] Cf. Portugal, Arquivo Histórico-Diplomático do Ministério dos Negócios Estrangeiros (AHD), PAA 308; e P. 2, A. 59, M. 351.

http://www.contramare.net/site/luso-tropicalism-and-portuguese-late-colonialism-part-2/

[iv] Circular n.º 3 do MNE, enviada às embaixadas, legações, consulados e delegações de Portugal. PT/AHD, PAA 308.

http://www.contramare.net/site/luso-tropicalism-and-portuguese-late-colonialism-part-2/

[v] Ofício n.º 102 da Comissão Executiva do V Centenário da Morte do Infante D. Henrique – Congresso Internacional de História dos Descobrimentos, 16 January, 1962. PT/AHD, PAA 308.

http://www.contramare.net/site/luso-tropicalism-and-portuguese-late-colonialism-part-2/

[vi] AmílcarCabral talked about “a powerful propaganda machine put in place to convince international public opinion that our peoples lived in the best possible world. […]. And, as in so many myths, particularly those concerning the subjection and exploitation of people, there were «men of science», including a well-known sociologist to provide the theoretical basis – in this case, Luso-Tropicalismo. […] And successfully as demonstrates an incident that occurred at the African Peoples Conference in Tunis in 1960, during which it was difficult to make our voices heard. An African delegate to whom we tried to explain our situation replied sympathetically: «Oh, but it’s different for you. You don’t have problems – you are fine with the Portuguese».” (Amílcar Cabral. 1975. “Prefácio”. In Basil Davidson. A libertação da Guiné. Lisboa: Livraria Sá da Costa. p. 3).

[vii] “Interview to Life Magazine, New York, May 4, 1962” (Salazar 1967: 84).

[viii] “Interview to the weekly U. S. News and World Report, New York, June 9, 1962” (Salazar 1967: 125).

[ix]“Interview to the newspaper group Southam from Canadá, december, 1962” (Salazar 1967: 156).

[x] Apontamento n.º 72 – “Projecto de normas de carácter permanente para uso interno da Direcção dos Serviços de Censura com relação ao Ultramar” – by Eduardo Freitas da Costa (July, 1960). Portugal, Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino (AHU), PT/AHU/MU/GNP/158/cx. 1.

[xi] Comentário n.º 263, 5.9.1961, signed by Eduardo Freitas da Costa, under the title “Caminhos de grandeza”. PT/AHU/MU/GNP/161/cx. 1.

[xii] Comentário n.º 201, 21.6.1961, signed by Eduardo Freitas da Costa, under the title “Fundamentação do portuguesismo”. PT/AHU/MU/GNP/161/cx. 1.

[xiii] Comentário n.º 183, 5.8.1964, signed by Carlos Maria Alexandrino da Silva, under the title “A verdadeira sociedade plurirracial: nós, portugueses, não somos «brancos»”. PT/AHU/MU/GNP/161/cx. 4.

[xiv] “I am convicted that it was during my courses of the discipline then called Overseas Policies thatlusotropicalismo became systematically taught and treated, inspiring numerous theoretical and field works” (Adriano Moreira. 1987. “Em lembrança de Gilberto Freyre”. Ciência & Trópico. 15(2): 191).

[xv] The proclaimed “Portuguese tradition” was not innate to the Portuguese, as it was made believe, but it was rather a geographical and historical situated model, which reported to the political and social situation of the local elites whom, until the second half of the 19th century were the base of colonial power in specific parts of Africa, that is, before the implantation of the modern colonial state and the establishment of migrant current from the metropolis to the empire (vd. Alexandre 1998: 207-208).

[xvi] Portugal, Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo (TT), PT/TT/AOS/CO/UL-37, Pt. 1.

[xvii] PT/TT/AOS/CO/UL-37, Pt. 2.

[xviii] Report dated from July 7, 1958. A copy was sent to the general governor of Mozambique by the general director of the Political and Civil Administration, on 31.1.1959. PT/AHU/MU/GNP/084/pt. 33.

[xix] On September 7, 1961, Adriano Moreira, sent the Government Gazette from the previous day to Gilberto Freyre, with the following note: “My Honorable Friend: I believe it is your interest to know the legislation printed on the Government Gazette I am sending you. Please note page 1129. I apologize for not writing more but I have very little time”. Brasil, Arquivo Documental Gilberto Freyre, Correspondentes Portugueses.

[xx] Instruções de APSIC (1970-1971), Conselho Provincial de Acção Psicológica de Moçambique, PT/AHU/MU/GNP/061/cx. 1.

[xxi] Copy of the dispatch nr. 11/971 of the meeting dated of 10.11.1971 by the province board for Psychological Action, general government of Mozambique, sent by the cabinet’s director of the mentioned organ, Custódio Augusto Nunes, to the cabinet’s director of the Minister of Overseas on 7.1.1972. The minister’s dispatch, J. Silva Cunha, was transcribed and sent by the director of cabinet for political affairs, Ângelo Ferreira, to the general governor of Mozambique, in a letter dated from 9.2.1972. PT/AHU/MU/GNP/061/pt. 1.