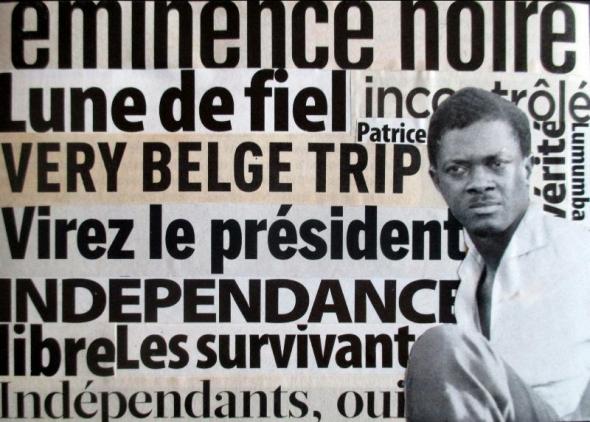

Patrice Lumumba, 60 Years Later

On January 17, 2021, the 60th anniversary of the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of the independent Congo (Democratic Republic of the Congo) and one of the great African leaders of the 1960s was marked. The historical relevance of this assassination includes local, regional and global factors ranging from internal rivalries and complicity to the importance of Congo as a reality and image in Africa; from the context of African countries fighting for independence to power disputes between the colonizing powers; and from relations between them in the context of the Cold War, the consequences of which are still felt today. In fact, it was a murder that was announced on independence day from a speech.

On June 30, 1960, at the ceremony for the proclamation of independence of the Congo, there were three speeches: from King Baudouin of Belgium, the former colonizing power, the President of the Congo, Joseph Kasavubu, and Patrice Lumumba, Prime Minister, the latter in an intervention not foreseen in the initial protocol. It was a short speech of about twelve minutes, written in an accessible and incisive language, performative and visual, a speech that, as the historian Jean Omasombo Tshonda defends, “founds the independent Congo”.1 The first eight minutes are the clearest definition of what colonialism is from the point of view of a continent, a country, a community, a person.

Lisette Lombé, in Black Words, Bruxelas, Arbre | 2018 | cortesy of the artist

Lisette Lombé, in Black Words, Bruxelas, Arbre | 2018 | cortesy of the artist

For Lumumba, what was at stake with the decolonization that independence brought, that the new world order coming out of post-World War II had offered as a promise and that the Bandung conference in 1955 had called for, was the launching of a new understanding of the world that would radically reimagine relations among people, peoples, communities and states. The promise was the struggle, for what was at stake was not just something national, but of the entire continent and all the subjugated peoples. “The independence of Congo marks a decisive step towards the liberation of the whole continent”.2 And, in fact, the impact of this discourse was national, continental and worldwide and even today the metamorphoses of this transnational and transcontinental history have ramifications in the most varied sectors of public and private life of contemporary European and African societies, translating into a renewed need to adjectivize the word decolonization - of the mind, of the imaginary, of being, of knowledge, of the arts, of narratives, of space, of people.

The ephemeral life of Patrice Lumumba, and of so many other African fighters murdered and imprisoned in what was thought to be the beginning of a path of liberation, shows how colonialism lingers in decolonization, overshadows independence, and haunts the postcolonial. In the same year, 1960, Patrice Lumumba, first prime minister of the independent Congo, was placed under house arrest in September, captured in November, and on January 8 wrote the last letter to his wife, Pauline, nine days before his assassination on January 17, 1961. In it he records the permanence of the old world from colonialism in metamorphosis to neo-colonialism in defense of the white bastion in Southern Africa of which his imprisonment is an expression, combined with the new world that emerged from World War II, the Congo being one of the nerve centers of Cold War confrontation in Africa. The assassination of Lumumba reveals the steps of this policy on the continent, executed by its Congolese rivals and Belgian officials, with the consent of the United States and the vigilance of the CIA, in its policy of combating communist action in the world led by the Soviet Union, and in its solid and historic relationship with Belgium in terms of exploitation of the resources of the “colony”. But in this letter, Lumumba also affirms the certainty in the continent’s final victory:

We are not alone. Africa, Asia and free peoples will always be on the side of the millions of Congolese who will not give up the struggle while the colonialists and their mercenaries remain in our country.

Two images will remain in the collective imaginary: the image of the young Prime Minister, the triumphant leader of the independence discourse, who touches everyone and represents the new world; the image of Patrice Lumumba with his hands tied behind his back, surrounded by the military and, with them, the symbol of a future still imprisoned by the colonial hand, which marks the suffering face of the leader and, with him, of all the Congolese people and all the peoples subjugated by an old world. And ends his letter to Pauline, looking at future generations:

History will one day reveal its verdict, but it will not be the history that will be taught in Brussels, Paris, Washington, or the United Nations; it will be the history that will be taught in countries freed from the yoke of colonialism and its puppets.

45 years after Patrice Lumumba’s speech and a very active neo-colonialism, Belgium would open a parliamentary inquiry into the death of Patrice Lumumba, to which Adam Hochschild’s books, King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa, were published in 1998, and, in 1999, Ludo De Witte’s The Assassination of Lumumba.

What everyone knew and no one pronounced was timidly concluded: Belgium’s “moral” involvement in the murder of the young leader, confirming what his companion in arms, Amilcar Cabral, had written in February 1961 in his text “Lumumba died so that Africa may live”3. This was followed in 2002 by a formal apology from the Belgian state to Patrice Lumumba’s family, and thus the “public secret”4that had long haunted Belgium began to be unveiled, with all the phantasmatic images of a young Congolese prime minister murdered with his companions, dismembered and dissolved in acid, of what would have been two teeth left, and Belgium’s support for the terrible dictator Mobutu, who would rule the Congo for decades. This opened up the possibility that, one day, another story would also be taught to all Belgians and all Europeans, and the process of decolonization would continue its path in Africa and Europe. This is what we continue to witness today.

Patrice Lumumba was named after a small square in Brussels in April 2019, the then Belgian Prime Minister, Charles Michel, addressed an official apology to the Belgian half-breeds torn from their African mothers and interned in institutions in Belgium during the colonial period, We witnessed the long judicial process of Patrice Lumumba’s sons regarding the return of his father’s mortal remains, and also, within the framework of the Black Lives Matter movement, the decisive interventions on the statues of King Leopold II, which itself epitomizes the brutal memory of colonial Belgium that Patrice Lumumba described in his speech. These are the words of this speech taken up by Pitcho Womba Konga, a Belgian performer, actor and rapper, in the play Kuzikiliza (2017), a title that, translated from Swahili, means “to make oneself heard. In the performance, the actor creates the conditions for listening to his speech written by Lumumba’s words, showing his actuality and the stages of decolonization yet to be accomplished. It is also Lumumba’s words that the poet and slammer Lizette Lombé updates in her poem, pronounced in post-colonial Belgium where both artists live. This is how Patrice Lumumba’s post-memory puts her words today on continued silence:

Who will forget?

That a black man was called by “you”…

Not like a friend, of course,

But because “Sir”, respectfully, was reserved to the

White.

Who will forget?

They told me

You are a scarab! A great monkey! A cockroach!

They told me

You are a pig! Fucking black!

Your mother slept with a nigger!

You’re the daughter of herbs!

They told me

You should go back to your land! Back to the bush!

To your hut!

You should go back to your tree! Your vine! Your bananas!

You should thank Belgium for taking you in!

Even if you were born here…

Who will forget?

That a black man was called by “you”…

(…)Who will forget?5

None of the artists experienced colonialism in the Congo, not even the official period of decolonization, but their speeches show us that the colonial act did not end with those who practiced it and with the historical framework that led to political independence, nor did decolonization take place in its fullness of restitution.

On 30 June 2020, Philippe, the King of the Belgians, who is now the age of independent Congo, acknowledges for the first time the pains and humiliations inflicted on the Congolese people and their present extensions in a letter addressed to the President of the Democratic Republic of Congo Félix Tshisekedi. In his words: “I wish to express my deepest sorrow for the wounds of the past, the sufferings and humiliations inflicted on the Congolese people whose pain is now rekindled by the discrimination still present in our societies.6 In a cross-mail the same day, the daughter of Patrice Lumumba, Juliana Lumumba addressed the King of the Belgians asking that the remains of her father be returned to her family and to the Congo.

60 years after the speech of Patrice Lumumba who founded the Congo and condemned its author, the King of the Belgians comes close, in a semantic and politically dialogical way, to the speech of Patrice Lumumba and opens a process of revisiting history, archives and memory, proposing a Commission of Truth, Reconciliation and Restitution. In parallel, and through the judicial and royal system, Belgium will return to Patrice Lumumba’s family the remains that one of the Belgian officers involved in the murder had sinisterly kept for himself and which have long haunted the Belgian imaginary. In this national environment of great change, but also of global awareness of the impact of brutal past on our present, which the Black Lives Matter movement represents, and following the resolution of the Brussels Parliament in April 2019 which favors the repatriation of remains and objects brought to Belgium during the colonial period, six institutions, launched the HOME project, whose goal is to give peace, repatriation and burial to the remains of many colonized black bodies that were brought to Belgium in the colonial period, as trophies of conquest, as objects of study, as beings to exhibit, as bodies of work.7

A new phase of decolonization is perhaps now beginning, in which Belgium begins to look at its colonial ghosts and begins a process of decolonization of its former colony. Perhaps one day the dream enunciated by Patrice Lumumba in his last letter to his wife Pauline will be fulfilled in another way, and it will be possible for Belgian and Congolese children, European and African children to learn their part of the common history of their countries, respecting the different memories and refusing the logics of oblivion.

MEMOIRS is funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research & Innovation Framework Programme (No. 648624);

MAPS Post European Memories: a post-colonial mapping is funded by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT - PTDC/LLT-OUT/7036/2020).

The projects are based at the Centre for Social Studies (CES) of the University of Coimbra.

- 1. Tshonda, Jean Omasombo (2020) La Décolonisation du Congo belge. La gestion politique des 24 derniers mois avant l’indépendance, Tervuren: AfricaMuseum.

- 2. All quotations are from Patrice Émery Lumumba (2018) Chora, Ó Negro, Brother Bem-Amado, Falas Afrikanas. (translation by Apollo de Carvalho, José Santy Jr. and Zetho Cunha Gonçalves), pp. 18, 24.

- 3. Cabral, Amilcar “Lumumba died, that Africa may live, 1961,” in Chora, Ó Negro, Irmão Bem-Amado, pp. 27-38.

- 4. Michael Taussig, (1999), Defacement: Public Secrecy and the Labor of the Negative. Stanford, Stanford University Press. p. 6.

- 5. Lombé, Lizette (2018) Black Words, Paris, L’Arbre à paroles. Published in Portuguese in Memoirs Público Encarte, 2018, p. 17. (translation by Fernanda Vilar and Felipe Cammaert, revised by António Sousa Ribeiro).

- 6. “Philippe, the king of the Belgians, expresses his “deepest regrets” in Congo, 30 June 2020

- 7. HOME - Human remains Origin(s) Multidisciplinary Evaluation é um projeto científico federal lançado em 2019, com quatro coordenadores e seis instituições. Mais informação aqui.