Tufo dance: Cultural heritage of Mozambique

Women come together to perform Tufo wearing capulanas and bright-coloured shirts. Their faces are covered with mussiro, a type of facial cream used by Macua women. They tie head wraps and use jewellery, necklaces and bracelets for an extravagant finishing touch.

Tufo had an Arab origin but took root on the east coast of Mozambique, particularly in Nampula and Cabo Delgado. This cultural manifestation will be considered for intangible cultural heritage of humanity, but little is known at this stage.

Zaquia Rachid, 47 years old, self-styled Queen of Tufo, has practised since she was 10. She joined the Tufo group of Mafalala in 2000 after the death of her father-in-law. “When Malatana Saide was on his deathbed, he left the group in my hands. It is singing and dancing ever since then,” she happily recalls. For her, Tufo is a therapy. “When I dance, all the worries that trouble my heart disappear, and I forget the pain and get back to being happy.”

Symbolism of the dance

Mussiro is not a part of the dance, but women apply it to identify more closely with their land. “To feel good, to be assured that I am performing a dance of my homeland, I have to use mussiro. This product makes me feel that I am a mutiana orera (woman) of Nampula, a Mozambican woman,” explains Zaquia.

Tufo dancers are vain. For performances, women make sure they are beautifully dressed and use makeup and other accessories to achieve the best look. “Earrings, bracelets and rings are spoils. Capulanas and head ties are must-haves. I like lively colours. In fact, we all like to be appreciated. We want to draw the public’s attention when we dance,” states the Queen of Tufo.

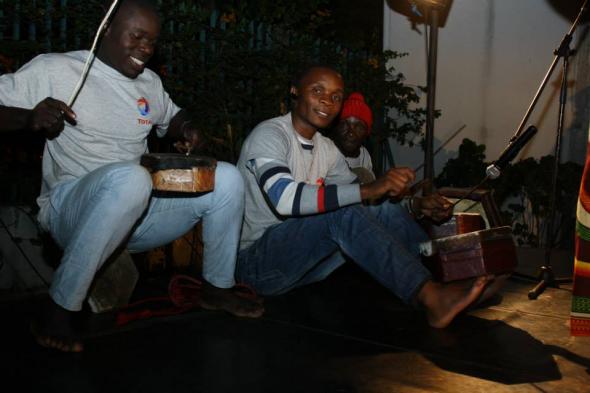

In a performance, women skip rope as men beat the tambourine. Zaquia says that the rope, ntxoco in Macua, was used by children in games but they borrowed it for the stage. In shows, there are generally mats that protect the dancers from dirt.

Group routine

The group Tufo da Mafalala is made up of more than 30 members, including family and friends, who joined voluntarily. It is led by the 55-year-old Momade Matano Saide. His wife is responsible for the coordination of compositions and choreography. Their children are instrumentalists. The remaining dancers are friends.

Founding

Momade Said recalls that the group started in Nampula. “It appeared before I was born. Matano Saide, my father and founder of the group, lived in Nampula. It was a family association, and only men could join. Women were included later,” says she.

In the early seventies, Matano Said, receiving an invitation from fans, moved to the neighbourhood of Mafalala in Maputo to teach the dance.

Momade explains that in the late eighties he had to take over due to his father’s poor health. “In the beginning I was not very interested, but I had to do it because my father was growing old and could not lead the group on his own. One day, in 1989, my father called for me and presented me to the rest of the group, saying ‘today my son will lead the group and you shall respect him’. It was a lot of responsibility, but I adapted to it and I am now group leader.”

Happy moments

As a group, Tufo de Mafalala had its happy moments, which Momade and Zaquia recall with alacrity. “Our trip to South Africa in 2003 was unforgettable, truly one of a kind,” recollects the Queen of Tufo emotionally.

“The year 2009 was a memorable one for us. We participated in a festival in Algeria. We shared the stage with international artists, renowned in Africa and in the world. I shook hands with Salif Keita, the musician, among other professionals in this field. This year we put together a piece in honour of Paulina Chiziane e Ungulane Bhaka Khosa. It was a unique moment for us”, recalls Momade proudly.

Troubling moments

It was not a bed of roses for the group. “We have to deal with negative experiences. Our group does not have the recognition that it deserves, and we are not valued. Our government does not appreciate the group. We perform at receptions in the airport because we love our government. However, getting water for the performers is sometimes a problem. They call us but do not pay us”, complains Momade.

The Queen of Tufo goes further and claims that “the government does not care about traditional dances. We sing and dance with all our heart. The government does not wish to support us”.

Difficulties

There are daily challenges, from the maintenance of instruments to the purchase of costumes.

“The maintenance of instruments is expensive. The specialists are in Nampula. For instance, a cut of skin for drums costs 10.000 meticais”, frets Momade.

We get all the garments we need thanks to our hard work. We live for Tufo. We sell donuts, samosas, rissoles and jewellery. We are quite a group now, but we do not have transport of our own yet”, says Zaquia bitterly.

Dreams

Amid difficulties and problems, several dreams have come true for this group. “We dreamed for transport and for a profession on top of dancing. We are not educated. We are hard-workers, but we do not have financial stability,” states Zaquia.

Momade adds: “How I wish we could perform abroad, outside of Mozambique! We hosted several tourists in our house. I hope that, one day, one of them will remember to invite us to their country.”

Promoting Tufo dance to intangible cultural heritage of humanity

In 2012, the Minister for Culture, Armando Artur, announced that Mozambique would suggest that Tufo be included on the list of intangible cultural heritage of humanity. Some years passed, and the minister’s declaration was not executed. For the project to go through, there are important steps to be taken.

Qualifying condition

UNESCO protects the immaterial heritage of member countries. For a country to be a member of this international organization, the first condition is to ratify and accept the conventions. Mozambique is a member country of UNESCO. It ratified the conventions.

According to Ofélia da Silva, representative of UNESCO in Mozambique, “all member states may propose the elevation of a cultural good to intangible cultural heritage of humanity; such a proposal has to be first made to the Ministry of Culture of the Mozambican government, who will then submit the proposal to UNESCO.”

Additionally, in order to apply for this status, a stock-taking is necessary in order to understand the genesis of this cultural manifestation: who practices it, where it is practised, what traditional rituals, when it is practised. All this information is collected through inventory checking, conducting interviews, surveys, filming and recording.

Sometimes the member-states of UNESCO do not possess the resources for effective execution of such. According to the same UNESCO Mozambican representative, “when this happens, the government can submit a request for technical support, and UNESCO may allocate a fund of up to 25.000 dollars. Besides, UNESCO dispatches technicians to take stock and write the final report.”

Ofélia da Silva revealed that the Mozambican Ministry for Culture already solicited technical support in 2013 for Tufo, Mapico and Xigubo dances. However, as he clarified, “this was agreed in a less than formal meeting, and for that, UNESCO and the Ministry will need to discuss the details yet.”

The final condition is to draw up programmes of preservation which outline strategies to train new dancers.

Importance of the promotion of Tufo

For Ofélia da Silva, promoting Tufo to intangible cultural heritage of humanity is a positive move because it is in line with the programmes and objectives of UNESCO.

Proposing Tufo is preserving it. On top of UNESCO recognition, it will stand better chances of spreading to other parts of the world. Appreciating the dance is promoting the cultural diversity of Mozambique. The world will remember that our country has a dance named Tufo,” concludes Silva.

Activities of the Ministry in coordination with ARPAC

The Ministry for Culture refused to comment, but sources close to it indicate that activities are taking place in favour of an application. At the same time, ARPAC, through one of its researchers, Sérgio Manuel, is compiling the materials. “There were expeditions, trips to various provinces, to assess the situation,” confirms Sérgio.

Dance history

A study by Álvaro Pinto de Carvalho which gathers Muslim writings on habits, traditions and costumes, published in Mozambique in 1969, points out that Tufo is an Arab word, meaning a dance of religious nature accompanied by the sounds of tambourine.

According to the study, the dance was born on the day the prophet Mohammad entered the city of Yterib (or Medina today) in 622AD. The “followers” of the prophet went to wait in the city and demonstrate their joy they felt in adhering by the doctrines of the Quran that the prophet brought with him.

ARPAC archive shows that the dance was introduced to the coast of Mozambique by Arab-Swahili merchants several centuries ago. Tufo, therefore, has strong religions roots. The same archival documents reveal that, in its origin, the dance was only performed in rituals and festive moments associated to the Muslim faith, but with time the dance was popularized and secularized.