Moving Image in Portuguese (Post-)Colonial Situation(s)

In 2015, four African nations previously colonized by Portugal – Angola, Cape-Verde, Mozambique and São Tomé and Principe – celebrated forty years of their independence1. In different countries, this anniversary gave way to a number of events, ranging from official commemorations to academic conferences and film retrospectives, the latter evincing the role that moving images play and have played not only as historical documents and sources, but also as a means of imagining, maintaining and projecting nationhood.

In 2015, four African nations previously colonized by Portugal – Angola, Cape-Verde, Mozambique and São Tomé and Principe – celebrated forty years of their independence1. In different countries, this anniversary gave way to a number of events, ranging from official commemorations to academic conferences and film retrospectives, the latter evincing the role that moving images play and have played not only as historical documents and sources, but also as a means of imagining, maintaining and projecting nationhood.

This important anniversary is the starting point for this collection of essays, which aims to explore the multiple ways in which Portuguese colonialism has been imagined by means of moving images. (Re)Imagining African Independence. Film, Visual Arts and Fall of Portuguese Empire assembles, among others, a number of contributions presented and discussed at the international conference Liberation Struggles, the Portuguese ‘End of Empire’ and the Birth (Through Images) of the African Nations, held on 27 and 28 January, 2016, at the Centre for Film Aesthetics and Cultures (CFAC), at the University of Reading, and at King’s College, London - Camões Centre for Portuguese Language and Culture, and organized within the framework of Maria do Carmo Piçarra’s post-doctoral project. However, the thoughts and analyses proposed here are not limited to the complex events that led to – and that occurred shortly after - the political emancipation of the five countries mentioned above. While exploring in some detail the audio-visual registers and direct outcomes of this unique and momentous occasion, the scope of this book encompasses a wider geographical and chronological spectrum, albeit related to what we could generally call the Portuguese (post-)colonial situation, i.e. the ever-shifting configuration of historical circumstances and discourses that determined – and still determine - the ways through which Portugal and the countries (formerly) under its influence and/or economic and political domination came to conceive, imagine, exert and withstand, discuss and recall the multiple instances of colonial power. Even though the book doesn’t undertake an exhaustive survey and analysis of the filmic and audio-visual materials that have shaped and re-shaped the imaginaries of Portuguese colonialism during and after the Estado Novo regime (Salazar’s New State), its aim is to contribute to this thriving field of studies. If studies on how cinema has represented the former European colonies are still scarce, most are also relatively recent, thus indicating that the research on colonial and post-colonial themes is gaining in importance, as illustrated, in particular, by the Portuguese example.

[…]

As previously mentioned, the starting point of this book was the celebration of the independence of Angola, Cape-Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique and São Tomé e Príncipe. Subjacent to this anniversary stands the historical fracture embodied by the events of 1974 and 1975, a fracture that marks the transition to complex post-colonial situations, i.e. what came after Portugal withdrew from its overseas possessions and colonial domination came to a political end. In this sense, post-colonial situations are as deeply entangled in geopolitics and power relations as colonial situations, our use of the term being more descriptive than evaluative. As Peter Hulme writes, the word postcolonial ‘refers to a process of disengagement from the whole colonial syndrome, which takes many forms and is probably inescapable for all those whose worlds have been marked by that set of phenomena’ (1995: 120). Along these lines, all of the essays collected in this book respond to the process in question, without being explicitly anchored in postcolonial studies.

As mentioned above, the aim of (Re)Imagining African Independence. Film, Visual Arts and Fall of Portuguese Empire is not to undertake an exhaustive survey and analysis of the filmic and audio-visual materials related to the Portuguese post-colonial situation. This collection of essays proposes, more modestly, and first of all, to contribute to a better knowledge of political propaganda films shot during and straight after the liberation wars. Shot by African and foreign filmmakers in different contexts and according to different agendas, these films allow us to explore such diverse questions as how the liberation struggles and Portuguese colonialism were envisaged according to opposing cold-war and geopolitical rhetorics, or how the newly independent countries imagined themselves as nations. Secondly, the book also highlights common aspects concerning the emergence of ‘national’ cinemas, in particular in Angola and Mozambique (the case of Guinea-Bissau being here, for circumstantial reasons, only marginally evoked). If these countries’ filmic productions have all started to be studied individually, this book demonstrates that an articulated study can and must be made. Furthermore, such an investigation inevitably leads us to cross the experiences of the Portuguese Novo Cinema, Third Cinema, the Brazilian Cinema Novo, Cuban Cinema, etc. Thirdly, the book also explores how the colonial past and the liberation struggles have been – and are being - dealt with, in terms both of collective memory and contemporary artistic practices, bringing to the fore the question of the post-colonial archive.

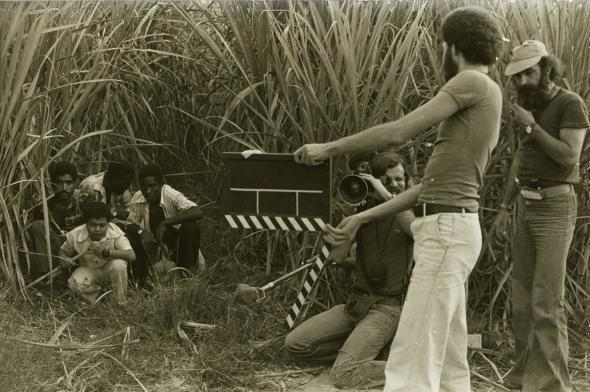

Duarte and TPA team filming their ‘cinema of urgency’ © João Silva

Duarte and TPA team filming their ‘cinema of urgency’ © João Silva

The first section of the book, ‘The Birth [Through Images] of African Nations’, highlights some of the representations ‘in reverse shot’ in terms of the official representations of Portuguese colonialism. ‘Ruy Duarte: a Cinema of the Word Aspiring To Imagine Angolanness’ analyses how the poet and anthropologist Ruy Duarte activated and participated in what he baptized a ‘cinema of urgency’ which, after the beginning of Angola’s Independence process, registered ways of life and traditions while filming the birth of the country. Maria do Carmo Piçarra reflects on Duarte’s work as a filmmaker, keeping in mind the disagreement between Jean Rouch and Ousmane Sembène in 1966 regarding cinema and anthropology. She also discusses Duarte’s filmography in its search to find a line of balance between two dynamics – the time of the Mumuhuila ethnic group and that of the Angolan present. Finally, she examines what place the film Nelisita occupied in the construction of a ‘delicate compromise’ between the new Angolan State, Ruy Duarte and the crew from the State-owned Televisão Popular de Angola that backed him up, and the people, who testified and were placed in front of the cameras.

Raquel Schefer analyses Mueda, Memória e Massacre (1979-1980) by Ruy Guerra, considered to be the first Mozambican fictional feature film. Shot in 1979 on the Makonde Plateau, it documents a carnavalesque reenactment of one of the most important events in the history of decolonisation in Mozambique, the Massacre of Mueda. In ‘Between the visible and invisible: Mueda, Memória e Massacre (1982) by Ruy Guerra and the Cultural Forms of Makonde Plateau’, Schefer assesses the influence of Makonde culture - and in particular of the Mapiko dance – on Mueda, Memória e Massacre’s aesthetic and discursive forms.

In ‘Clear Lines on an Internationalist Map: Foreign Filmmakers in Angola at Independence’, Ros Gray considers two of the lines – the Cuban and the French - of internationalist solidarity with the MPLA which produced cinematographic co-work. Gray concentrates on some films produced from 1975 to 1977, considering that these films raise significant questions about militant cinema and the ways in which its role in the internationalist anti-imperialist struggle was understood in the late 1960s and 1970s.

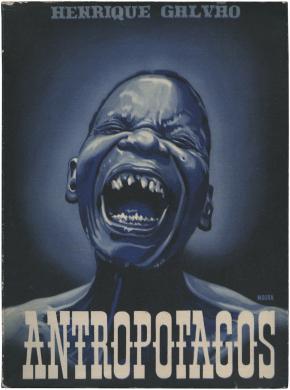

Book cover illustration by José Moura for Henrique Galvão’s Antropófagos (1947). Illustration by José de Moura © José de MouraIn his essay, Robert Stock analyses three documentary films referring to the Wiriyamu massacre (Mozambique). Focusing on 25 (José Celso and Celso Lucas 1976), Treatment for Traitors (Ike Bertels 1983) and the TV documentary Regresso a Wiriyamu [Return to Wiriyamu, Felícia Cabrita and Paulo Camacho, 1998], Stock shows how the massacre was cinematographically negotiated, insisting on the different ways of seeing the past and interpreting colonial violence. While 25 is indebted to theatrical performances, exploring forms of the survivors’ ‘silent testimony’, Treatment for Traitors (1983) calls a former colonial soldier to the witness stand, a strategy that should be read in the context of the war between FRELIMO and Resistência Nacional Moçambicana (RENAMO) [Mozambican National Resistance]. Finally, Regresso a Wiriyamu places perpetrators and survivors face to face at the scene of the crime, carrying out important memory work but nonetheless perpetuating a ‘double victimization’ type of discourse involving the victims and the soldiers that is still patent in Portugal today.

Book cover illustration by José Moura for Henrique Galvão’s Antropófagos (1947). Illustration by José de Moura © José de MouraIn his essay, Robert Stock analyses three documentary films referring to the Wiriyamu massacre (Mozambique). Focusing on 25 (José Celso and Celso Lucas 1976), Treatment for Traitors (Ike Bertels 1983) and the TV documentary Regresso a Wiriyamu [Return to Wiriyamu, Felícia Cabrita and Paulo Camacho, 1998], Stock shows how the massacre was cinematographically negotiated, insisting on the different ways of seeing the past and interpreting colonial violence. While 25 is indebted to theatrical performances, exploring forms of the survivors’ ‘silent testimony’, Treatment for Traitors (1983) calls a former colonial soldier to the witness stand, a strategy that should be read in the context of the war between FRELIMO and Resistência Nacional Moçambicana (RENAMO) [Mozambican National Resistance]. Finally, Regresso a Wiriyamu places perpetrators and survivors face to face at the scene of the crime, carrying out important memory work but nonetheless perpetuating a ‘double victimization’ type of discourse involving the victims and the soldiers that is still patent in Portugal today.

The second section of the book, ‘The Fall of the Portuguese Empire: Foreign Gazes During the Cold War’, presents and explores some of the foreign gazes focusing on Portuguese (ex-)colonies across Africa and Asia, during the liberation struggles and the emergence of the new Portuguese-speaking African countries. While the Lopes and Ramos chapters highlight the differences between fictional and documental North-American audio-visual discourses about Portuguese colonialism before the Carnation Revolution granted independence to the former Portuguese territories in Africa, Vasile shows how Ceausescu’s official visits to Angola and Mozambique in the 1970s and 1980s were photographed picturing the Romanian totalitarian regime’s relations with these new socialist African countries.

The essay on ‘The US and Portuguese colonialism as imagined through television drama’ contributes towards an understanding of North-American discourse about the Portuguese empire presented to the public, by examining how television drama, made in the United States in the 1950s and very early 1960s, engaged with the topic. Rui Lopes describes how television series at first channelled an idea of partnership against common threats and, later, even when the US had become disenchanted with Portugal’s colonial rule, it continued to portray the metropolitan authorities as valued allies. As Lopes shows, the choice of Macao as setting – a territory under Portuguese administration – was symptomatic of the USA’s will to overlook the liberation struggles taking place in Africa.

‘“Rarely penetrated by camera or film” - NBC’s Angola: Journey to a War (1961)’ analyses unexplored material about the documentary directed by Robert Young and Robert McCormick. As part of NBC’s groundbreaking series ‘White Papers’, Angola: A Journey to a War was touted as the first international television coverage of the liberation war in Angola and as a uniquely balanced portrait of both sides of the political fray. Afonso Ramos undertakes careful consideration of the documentary’s context and content in order to unpack these claims, reading them against the militant efforts that prompted this visual record as well as the propaganda battles that ensued over it.

‘‘The Party, the Leader, Romania’: Colonialism and Independence within the Socialist Republic of Romania Photographic Frame’ looks into the photographic archive of the Romanian National Archives, focusing on Ceausescu’s official visits to Angola and Mozambique in 1970s and 1980s. The chapter examines the official relations between Ceausescu’s regime and Angola and Mozambique so as to analyse the propagandistic uses of photographs as means of political engagement. Iolanda Vasile identifies the role that the memories created by the uses of propaganda images played - and still play – in the rewriting of history itself.

The third section of the book, ‘Moving Images, Post-colonial Representations and the Archive’, focuses on the present moment, and seeks to understand some of the issues concerning preservation and the restitution of public archives to the public. Also under consideration is how and to what extent, postcolonial cinema, as well artistic practices and research work that use the moving image, have helped towards decolonising different imaginary universes. Very often based on archival explorations, many of these contemporary works are also a way of questioning collective memory and its silences.

In ‘Colonial Collection of the Portuguese Film Archive. Shot, Reverse Shot, Off-Screen’ (a transcript from the author’s keynote intervention at the international conference Liberation Struggles, the Portuguese ‘End of Empire’ and the Birth (in Images) of the African Nations), the director of the Portuguese Cinemateca, José Manuel Costa, provides a succinct but useful overview of some of the aspects of the Portuguese colonial film collection.

Ana Balona de Oliveira discusses how contemporary artistic practices have been working towards a decolonization of the present by means of critical examinations of several kinds of colonial and post-colonial archives. Taking three artworks by Ângela Ferreira (b. Mozambique, 1958), Kiluanji Kia Henda (b. Angola, 1979) and Euridice Kala (b. Mozambique, 1987) as case studies, ‘A Decolonizing Impulse: Artists in the Colonial and Post-Colonial Archive, Or the Boxes of the Departing Settlers between Maputo, Luanda and Lisbon’ examines these artworks’ relevance to thinking critically about the post-colonial condition. Oliveira proposes that this post-colonial condition is ‘marked by neo-colonial patterns of globalization and by uneasy relationships with diasporic and migrant communities in Lusophone contexts (and beyond)’.

Euridice Kala, Will See You in December … Tomorrow (WSYDT), 2015. Installation view, Will See You in December … Tomorrow (WSYDT), MUSART Museu Nacional de Arte, Maputo, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

Euridice Kala, Will See You in December … Tomorrow (WSYDT), 2015. Installation view, Will See You in December … Tomorrow (WSYDT), MUSART Museu Nacional de Arte, Maputo, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

Manuel Santos Maia, alheava-film (2006–2007). Courtesy of the artist.

Manuel Santos Maia, alheava-film (2006–2007). Courtesy of the artist.

In ‘In-Between Memory and History: Artists’ Films and the Portuguese Colonial Archive’, Teresa Castro questions the way in which a growing number of Portuguese artists and filmmakers have been undertaking more or less detailed explorations into some very specific aspects of Portugal’s recent colonial past. Despite their different strategies and results, films and installations by Manuel Santos Maia, Filipa César, Andreia Sobreira and Daniel Barroca all seem symptomatic of a peculiar situation, a sort of memorial turn, in which the complex relations between personal and collective memory are central. Castro argues, on the one hand, that such artists and filmmakers can be thought of as ‘artist-historians’, whose films and videos allow us to better understand the mnemonic processes at stake within the Portuguese memorial turn. Resorting to the Freudian notion of ‘afterwardness’, the author suggests, on the other hand, that such works conjure up the past, urging us to confront – and progressively historicise - individual and collective memories.

Finally, the book’s last section, ‘Rethinking (post-)Colonial Narratives: Artistic Takes’, includes three contributions by artists Daniel Barroca, Filipa César and Mónica de Miranda. Even though they illustrate specific ways of rethinking (post-)colonial narratives, we have decided to integrate them in other sections of the book, in order to stimulate what we believe are productive encounters and exchanges between strictly academic essays and more artistic takes. In our current post-colonial context, the (research) work developed by many artists today is yet another important way of questioning the past and reconfiguring the future. In themselves very different, the three contributions in question all illustrate the significance of the questions asked by artists.

Daniel Barroca’s autobiographical essay, ‘Drawing and Undrawing my Genealogy’, is a poignant and intelligent meditation on the way that the personal and the political are closely linked. Delving into a number of family portraits, Barroca sets out to investigate the fragmented lines that connect three generations in a Portuguese family against the background of fascism and colonial history. The first are his grandparents, a couple of farm workers from the libertarian Alentejo, which was violently oppressed by the political regime. The second generation is represented by his father, a conscript drafted to serve in Guinea-Bissau during the war, the son of the oppressed disguised in the oppressor’s uniform. The third generation is that of the artist himself, haunted by ‘an obscure feeling of guilt’. Drawing on multiple references, from Pasolini to the Portuguese anarchist Emídio Santana, Barroca sketches a complex history made up of breakages and open passages, and invites us to re-think the world by treading new paths.

The personal and the political are also present in Filipa César’s text, ‘A Grin Without Marker’, as the artist recalls the way in which the narrative around her father’s failed desertion to Paris and his military service in Guinea-Bissau found a disturbing echo in her discovery of Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil (1983). It was Marker who led her to travel to Guinea-Bissau and meet Sana na N’Hada (who had fought with Amílcar Cabral and had filmed with Marker in Guinea-Bissau). In Bissau, César discovered the country’s ruined Institute of Cinema, whose fragmented collection was judged ‘irrelevant’. César’s text is a powerful meditation on the ‘potencies of irrelevance’ and the reasons why she succeeded in involving the Institute Arsenal for Film and Video Art in Berlin in the digitization of the Institute’s audio-visual material.

Hotel Globo (2015) © Mónica de Miranda.

Hotel Globo (2015) © Mónica de Miranda.

Finally, Mónica de Miranda’s ‘Hotel Globo’ focuses on the homonymous installation (2015) by the artist. Hotel Globo is the name of a famous modernist hotel built in the city of Luanda in 1950 by a Portuguese émigré. Confiscated by the new independent state in 1975, and returned to the family in the 1990s, the hotel housed a number of unusual guests, from traders and refugees to militias, some guests still residing amongst its decaying walls. As the artist’s photographic images suggest, the ruined colonial building serves as a metaphor for the colonial past, but also for the social and economic wreckage brought about by Angola’s neoliberal situation.

By way of conclusion and in order to return to the idea that the post-colonial relates to a multifarious ‘process of disengagement from the whole colonial syndrome’ (Hulme 1995:120), we would like to inscribe this book in the context of Aleph’s activities. Aleph – Network for Action and Critical Research into Colonial Images, was created in 2015 with the purpose of launching a public debate on accessing collections of colonial images in Portugal. It informally gathers independent and affiliated researchers, artists and creators, programmers and curators, as well as scholars generally interested in (anti-/post-) colonial images. The first national archive to join forces with Aleph was the Portuguese Cinemateca – Cinema Museum, and the network’s first public event took the shape of a film screening entitled ‘Colecção colonial da Cinemateca: campo, contracampo, fora de campo’ [‘The Cinemateca’s Colonial Collection: Shot, Reverse Shot, Off-Screen’]2.

The Aleph network, being an action/research project, undertakes joint work with national and international archives holding colonial collections, in order to raise public and political awareness as to the importance of archive accessibility and the preservation of their collections. The Aleph also promotes cooperation and knowledge-sharing among researchers, in particular by means of the free access platform ‘Empire Cinema - Filmography of Portuguese Colonialism’ (in progress). The general goal of the ‘Empire Cinema Platform’ is to overcome the difficulty in accessing the filmed memory of (anti/post-) Portuguese colonialism, by means of filmography covering the titles present in the Portuguese Cinemateca’s archive. The platform, inspired by the database ‘Colonial Film. Moving Images of the British Empire’, will provide information and documentation on existing work, hopefully stimulating the production of critical knowledge as well as artistic creation based on this colonial archive of moving images. One of the reasons why these films are still so difficult to access today lies precisely in the lack of a filmography based on the titles held by the Arquivo Nacional de Imagens em Movimento (ANIM) [National Archive of Moving Images] or other archives and film collections. Researchers, artists and creators, as well as the general public, still do not know what is really available. Against this background, this book is a contribution to better and more accurate knowledge about how and with what films – colonial, postcolonial, neocolonial – cinema tells the history of Portuguese colonialism and of the new African countries, while also disclosing its own history.

References

Andrade-Watkins, Claire, ‘Portuguese African Cinema: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives: 1969 to 1993’, African Cinema 26/3 (1995), 134-150.

Barreto, José, ‘António Ferro: modernism and politics’, in S. Dix and J. Pizarro, eds, Portuguese Modernisms: Multiple Perspectives on Literature and the Visual Arts (Oxford: Legenda, 2001), 135-154.

Caetano, Marcelo, Razões da Presença de Portugal no Ultramar (Lisbon: Oficinas Gráficas da S.E.I.T., 1973).

Carvalho, Rui Duarte de, A Câmara, a Escrita e a Coisa Dita. Fitas, Textos e Palestras (Lisbon: Cotovia, 2008).

Convents, Guido, Os Moçambicanos Perante o Cinema e o Audiovisual: uma História Político-cultural do Moçambique Colonial até à República de Moçambique (1896-2010) (Maputo: Dockanema, 2011).

Costa, Catarina Alves, Guia Para os Filmes Realizados por Margot Dias em Moçambique 1957-1961 (Lisbon: National Ethnology Museum, 1997).

Freyre, Gilberto, O Mundo que o Português Criou (Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio Editora, 1940).

Frodon, Jean-Michel, La Projection nationale. Cinéma et nation (Paris: Odile Jacob, 1998).

Godard, Jean-Luc and Ishaghpour, Youssef. Cinema (Oxford: Berg, 2005).

Hulme, Peter, ‘Including America’, Ariel 26 (1) (1995), 117-123.

Martins, Leonor Pires, Um Império de Papel – Imagens do Colonialismo Português na Imprensa Periódica Ilustrada (1875-1940) (Lisbon: Edições 70, 2012).

Oliveira, Alexandre, Os Filmes de Ruy Cinatti sobre Timor, 1961 – 1962 (Lisbon: Museu Nacional de Etnologia, 2013 Multi-copied).

Piçarra, Maria do Carmo, Azuis Ultramarinos. Propaganda Colonial e Censura no Cinema do Estado Novo (Lisbon: Edições 70, 2015).

Piçarra, Maria do Carmo and António, Jorge, eds, Angola, o Nascimento de uma Nação. Vol. III O Cinema da Independência (Lisbon: Guerra & Paz, 2015).

Piçarra, Maria do Carmo Piçarra, ‘O Cinema é Uma Arma’ in Maria do Carmo Piçarra and Jorge António, eds, Angola, o Nascimento de Uma Nação. Vol. II O Cinema da Libertação (Lisbon: Guerra & Paz, 2014), 15-42.

Piçarra, Maria do Carmo and António, Jorge, eds, Angola, o Nascimento de uma Nação. Vol. I O Cinema do Império (Lisbon: Guerra & Paz, 2013).

Piçarra, Maria do Carmo, Salazar Vai ao Cinema. O ‘Jornal Português’ de Actualidades Filmadas (Coimbra: Minerva, 2006).

Pimentel, Joana, ‘La Collection Coloniale de la Cinemateca Portuguesa’, Journal of Film Preservation 64 (2002), 22-30.

Seabra, Jorge, África Nossa: o Império Colonial na Ficção Cinematográfica Portuguesa, 1945-1974 (Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra, 2011).

Torgal, Luís Reis, Ed., O Cinema sob o Olhar de Salazar (Lisbon: Círculo de Leitores, 2000).

Vargavtig, Nadia, Des Empires en carton. Les expositions coloniales au Portugal et en Italie (Madrid: Casa de Velazquez, 2016).

Vicente, Filipa Lowndes, O Império da Visão: Fotografia no Contexto Colonial (1860-1960) (Lisbon: Edições 70, 2014).

Vieira, Patrícia, Portuguese Cinema 1930-1960: The Staging of the New State Regime (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2013).

- 1. Portugal recognized the independence of Guinea-Bissau on September 10, 1974. However, the PAIGC National Assembly declared the independence of Guinea-Bissau on 24 September 1973 and was recognized by a 93-7 UN General Assembly vote in November.

- 2. Held at the Portuguese Cinemateca on 21 January 2015, the event was co-organised by Maria do Carmo Piçarra, the Portuguese Cinemateca - Cinema Museum, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, the Comparative Studies Centre, Faculty of Letters, University of Lisbon, the Portuguese Science and Technology Foundation (FCT) and the Communication and Society Research Centre (CECS), University of Minho.