Three films on the Africa Museum: PALIMPSEST, LOBI KUNA and DIORAMA

“Palimpsest of the Africa museum” documents the moving of the Africa museum as an esthetic mourning process, shows the insanity of the alterations and reveals through the eyes of the Belgian African Diapsora what the renovation really puts at stake: the decolonization of the Self.

Directed by Matthias De Groof in collaboration with Mona Mpembele.

Text and Voice: Jean Bofane.

Music: Ernst Reijseger.

Written by Matthias De Groof.

Produced by Cobra Films.

Cinematography by Matthias De Groof.

Edited by Sebastien Demeffe.

Release: 2018.

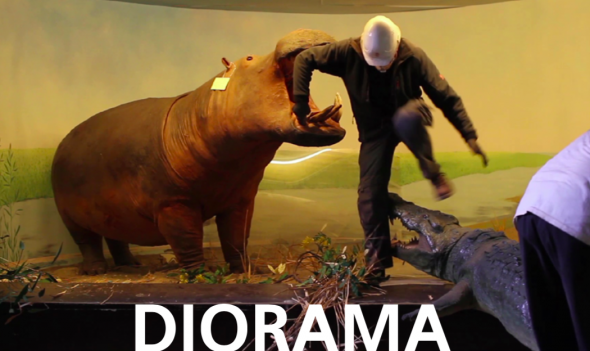

DIORAMA

When the staff of the Africa-Museum destroys the very dioramas they used to guard for decades, a colonial worldview is demolished. What remains are dead animals staring at you amidst ecocide.

“Diorama presents us with the documented deconstruction of a constructed habitat, a stage within a stage plays out before us in what appears to be an “Africa Museum” whose taxidermy exhibits are being dismantled. A sombre, abject humour permeates through these scenes as we witness, quite literally, the dissemination of history. The uninterrupted quietness of these dioramas is suddenly yet casually disrupted by the inherently ironic (re)destruc- tion of these animals’ “habitats”. We bear witness to fine examples of nature’s awe-inspiring animal kingdom reduced to utilitarian objects of burden - cajoled out of their static setting by a band of men, whose group dynamic suggests they are not accustomed to such an activity, if one could ever be.” - Ash Kerr

In the course of its renovations, Belgians colonial museum – or better: museum of colonialism ceases to exist. One of the pinnacles of this transformation is when the museum staff destroys the very dioramas they used to guard for decades. The violent destruction forms an allegory of museological and ecological relations. Not only the dioramas are demolished, but also a colonial worldview.

Diorama literally means “through that which is seen”. It is a window which wants to suggest life as truthful as possible through death, the sole thing it can resort to. Due to this, the diorama becomes a still life, a Vanitas. So still, that the sculptural becomes pictorial… until men enter the broken window and become part of the nature morte. Men animate death through caress and tear the animals loose from a morbid decorum that offered them verisimilitude of an obsolete landscape.

LOBI KUNA

The fiction film Lobi Kuna is told through the gaze of photographer Mekhar Kiyoso who is in the Africa Museum for a shoot. His gaze is soon unsettled as he views through his lens the macabre museum as a mausoleum of his cultural heritage. As he is being possessed by the artefacts, he remembers being alienated from them.

Lobi Kuna -which in Lingala means the day after tomorrow as well as the day before yesterday- tells the story of his appropriation of the past in order to project himself into a future, and this while the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren undergoes a metamorphosis through its renovations.

Lobi Kuna (avant-hier / après-demain) Fiction – 45’35” – HD – couleur – stéréo - vo fr et lingala / st en et nl Belgique / R.D.Congo

Realisation- Matthias De Groof, écriture - Mekhar Azari Kiyoso et Matthias De Groof; image - Hadewych Cocquyt (BSC), Sam Vanmaekelbergh, Carlo Lechea, Kiripi Katembo Siku et Matthias De Groof, son - Pol Van Laer; Montage - Sébastien Demeffe / Kwinten Gernay; avec Mohamed Boujarra, Francis Mampuya, Bart Maris, Jean Katambayi Mukedi, Mekhar Azari Kiyoso, Kjell Bracke; Prodution Cobra Films (Daniel De Valck & Anne Deligne) Mutotu Films (Kiripi Katembo Siku) et l’atelier Graphoui Avec le soutien de la VAF (Production, FilmLab)

Rendez les moi (work in progress)

The short film Rendez-les moi (Give me back my black dolls) which I made in 2013 during an IFAA-residency at Nijmegen, points to an interpretation of Limbé as an expression of a longing for a supressed African cultural heritage but which nevertheless can be found extensively in divers museums.

Rendez-les moi is a film which might be called a “visual poem”, using the technique of « caméra-stylo » or « camera pen » described by Astruc as a form in which and through which an artist is able to express his thoughts, tearing loose from the image for the image, of the immediate anecdote. In “Rendez-les-moi”, however, the camera is strongly guided by another poem: Léon Gontran Damas’ Limbé (Borders) as if Damas too was holding the pen.

His black dolls are being “prostituted” by the museum. Indeed, the artefacts function as “wenches” in the public space of the museum: undressed from their ritual costumes and put behind vitrines, they satisfy a western self-image as historically and racially superior. Detached from their context, they make their absent creators look foolish. Exhibited as commodities, they suggest an Africa totally at western disposal. Eagerly constructed as static and primitive, they become negative symbols of western historical progression. Invented as the remote and the past, they reinforce the west’s image as developed. Looted, traded and domesticated in time, they become the relics of a western past. Referred to as a variation of a western past existing in the present, they make Africa into Europe’s eternal museum. Ethnologized, they are ‘othered’ as remote and museified, they are historicized as past. Put at these distances in time as well as in space – making the distant into the past – they define the “Self” as measure, while making from Protagoras’ Homo Mensura doctrine Europa mensura. Categorized, they are constructed as primitive; assimilated, they are conceived of as barbarous and imagined as exotic.

Tervuren Invisible

Le Tervuren invisible is a critical interview with Francis Mampuya. This interview was done in Belgium, while Mampuya was here for a solo-exhibition in the framework of the Belgo-Congolese cultural project Yambi.

This video being made about one year after our stay in Congo, it not only takes a distance in time and space, but also a reflective and critical distance towards the other works of ôtre k’ ôtre.

In a reflection on the role of Belgian’s Royal Museum of Middle Africa, also called the Museum of Tervuren, Mampuya talks about its colonial role in the past and its current, more invisble but not less powerful role.

Moreover Tervuren becomes a metaphor for ‘white’ projects that, under the cloack of ‘cultural exchange’, aim at archiving and observing African culture.