Let’s talk about A House in Luanda

Around the competition A House in Luanda: Patio and Pavilion, let’s talk about houses and let’s talk about Luanda. Intending, with all this talk, to add a few considerations to the debate driven by the Lisbon Architecture Triennale, in association with the Luanda Triennale, on the role architects could play in the solution to the urban and housing problem of this city with explosive growth, to the increasing socio-territorial inequalities. Let’s talk about houses through an analysis of some of the ideas presented in the competition to which we’ll add others around the problems highlighted on a brief analysis of life in “Luanda’s perimeter”, the place proposed by the competition.

Foremost, let’s talk about A House in Luanda: Patio and Pavilion, an ideas competition to select the best proposal for a housing prototype for one family unit that could originate a patio, destined for families composed of 7 to 9 people in a deprived situation, in an area of plain topography, situated in the outskirts of Luanda. Other parameters referred to the area of the lot, about 250 m², to the gross area and to the cost of construction, around €25.000. The intent of this competition was to originate a reflection over low-cost housing solutions for the areas of informal housing in Luanda.

From within the 588 projects accepted by the competition, proceeding from 44 different countries, the jury selected a shortlist of 30 finalists, whose authors developed a model of their proposal currently exhibited in Lisbon’s Museum of Electricity and that, in 2011, will be presented in Luanda. From those 30 selected projects, the jury awarded 4 prizes and an honorable mention. We chose to talk about some of the projects, each with its own quality and interest, which point out questions: on the module “patio and pavilion”, on the type of urban structure, on different technological solutions, or even on the pursuit for the best strategy of intervention on the neighborhoods of informal housing of Luanda.

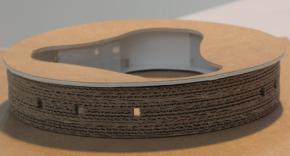

House in Luanda, projecto coordenado por Pedro Sousa, 1º Prémio.

House in Luanda, projecto coordenado por Pedro Sousa, 1º Prémio.

Around the module “patio and pavilion” we’ll start by talking about the winning project, presented by Bárbara Silva, Madalena Madureira, Pedro Sousa, Tiago Coelho and Tiago Ferreira (64), that proposes a “construction defined by six patios related to the different functions of the house” communicating with each other through an exterior central corridor protected from the rain. This proposal bets on the creation of a continuous module where exterior and interior spaces alternate, functioning as an extension of each other. The exploration of associations of this module to form an urban tissue demonstrates the potentialities of this proposal and its capacity of adaptation to “different stages of growth and different types of people”. Also for thought is the choice of pestle mud as the construction material, which raises the flag of earth construction. We can find some examples of this type of construction in the musseques, or better yet in the “neighborhoods” – as they are currently referred to in Luanda –, though with the use of other techniques: rammed earth (taipa) in the wattle and daub construction of some older houses, or the construction in adobe, a technique normally used by families originating from rural areas. In the neighborhoods, such construction techniques are associated to conditions of greater poverty and it is interesting to debate the different possibilities of building in earth, its problems and its advantages.

House in Luanda, projecto coordenado por Marco Silva.Another module is proposed by the project by Marco Silva and Nuno Costa Brás (173) that, in an interesting way, explores simultaneously the unity and the flexibility of the module “patio and pavilion”. It is set from a project of a house made of concrete blocks in three longitudinal wings, where the patio is the central organizational hinge, “mediator and generator of different modes of inhabiting”, relating the functional spaces of the house, disposed face to face, offering its inhabitants the possibility of creating continuities and discontinuities in accordance to their “wishes or necessities”. The three wings, central patio and lateral wings, create one sole structure “that transforms and actively adapts itself to the different uses of individual and family life”. That unity is emphasized by the folding panels, made out of local natural elements, that function as a double skin that externally coats all the spaces, and that, in an extreme situation of covering the whole patio, permit the creation of a “box” within which we can imagine a space with the intimacy and freshness that, according to necessities or interests, may be completely private, half-private or public.

House in Luanda, projecto coordenado por Marco Silva.Another module is proposed by the project by Marco Silva and Nuno Costa Brás (173) that, in an interesting way, explores simultaneously the unity and the flexibility of the module “patio and pavilion”. It is set from a project of a house made of concrete blocks in three longitudinal wings, where the patio is the central organizational hinge, “mediator and generator of different modes of inhabiting”, relating the functional spaces of the house, disposed face to face, offering its inhabitants the possibility of creating continuities and discontinuities in accordance to their “wishes or necessities”. The three wings, central patio and lateral wings, create one sole structure “that transforms and actively adapts itself to the different uses of individual and family life”. That unity is emphasized by the folding panels, made out of local natural elements, that function as a double skin that externally coats all the spaces, and that, in an extreme situation of covering the whole patio, permit the creation of a “box” within which we can imagine a space with the intimacy and freshness that, according to necessities or interests, may be completely private, half-private or public.

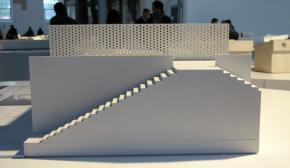

House in Luanda, projecto coordenado por João Gomes Leitão.

House in Luanda, projecto coordenado por João Gomes Leitão. House in Luanda, projecto coordenado por Ricardo Carvalho.

House in Luanda, projecto coordenado por Ricardo Carvalho.

In a different sense we find the module of the Baobab House, by João Gomes Leitão, Mafalda Ambrósio and Manuela Cabral (20) that, according to their authors, is the result of a research on the African circular plan house. This project develops a pavilion with a circular plan around a central intimate patio with an organic development. With this geometry they intend to concieve “more or less long spaces, creating an almost natural hierarchy of uses and velocities”. The implantation of the circular house in the urban tissue enables “a reach identical to that of a village, a small quarter with strong neighborhood bonds”. Potentiating this proposal, the creation of “urban voids”, connected organically thru the different implantations of the houses, with different dimensions, that may stimulate creativity, invention, conviviality and trade, being supported by an orthogonal grid of streets.

Another direction is pointed out by the project coordinated by Ricardo Carvalho (226) that foments reflection upon a proposal that starts out from a cylindrical patio constructed and involved by the pavilions, domestic spaces, with unconcluded functions, “the residents will be able to appropriate in an unexpected manner, divide spaces or change their use. But what distinguishes this proposal is the main façade of the house, represented by the exterior staircases that provide access to the terrace, which can be semi-private or public. It’s the continuity of the terraces that “generates an urban identity, where all activities may occur”. Thus, this proposal bets on placing spaces of reunion, sociability or trade on an upper level, defended from the road traffic occurring in the inferior streets.

The use of pre-fabrication was approached by some selected proposals, but it’s with the Brazilian team, coordinated by Álvaro Puntoni (67), that that concept is most explored. With one single piece in C of 2,5 x 2,5 x 10m of pre-fabricated concrete, diverse modules of “patio and pavilion” are sampled, with one or two floors, where the C’s add up or detach themselves forming patios or even superpose creating two floors. According to the authors, the use of only one pre-fabricated element enables the reduction of cost and time. Regarding this proposal, we recall the work of Brazilian pioneer architect João Filgueiras Lima, Lélé, in the use of pre-fabricated elements of reinforced mortar in communitarian equipments, mainly day-care centers and schools, as well as in infra-structures. We are left to reflect upon the pertinent option of creating and installing an industry, may it be micro-industry, or precast industry, or other, in the search for a solution of the social problem that follows, step by step, the housing problem of the informal neighborhoods in Luanda.

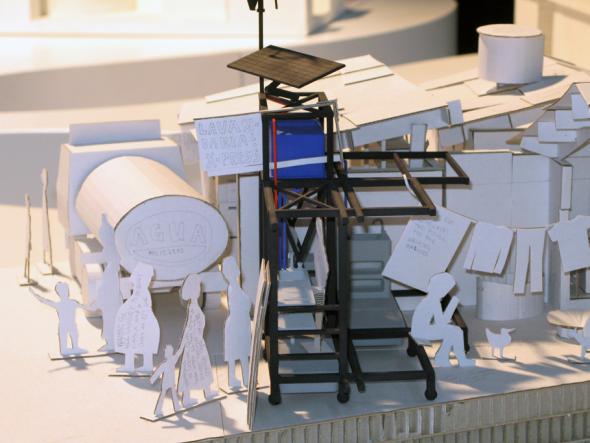

House in Luanda, projecto coordenado por Arne Petersen.

House in Luanda, projecto coordenado por Arne Petersen.

It is interesting as well to reflect upon the strategy proposed by Arne Petersen and Ulrich Schfferdecker (224) that consists of adding to each existing dwelling a dispositive they named Musseque 500, or M 500, that integrates sanitary, energetic and communication systems, adaptable to each space of the family unit or to its grouping. M 500’s objective is to upgrade the existing dwellings in musseques in relation to the new demands of habitation, through the use of sustainable technology and renewable resources consistent with local building methods and materials and, in this way, “opening the house to new possibilities of trade.” According to its authors, M 500 “intends to install a piece of future in the front patio of each house.” So, it is a proposal that aims to answer the different survival strategies and the will of modernity we can easily acknowledge in Luanda’s neighborhoods.

In addition to these thoughts, we can also talk about other issues that affect and condition life in these neighborhoods of endogenous formation and that, though not having pertinence in this competition, are central and should not be forgotten. Actually, the organic and diverse form we find in most of the neighborhoods isn’t the result of a freedom of occupancy but of the existence of multiple social and economical constraints as of different solutions tested on each case. On one hand, this casualness, the multiple processes, connected or overlapped, dependent of negotiating or intervenient power of the residents, of their management of the existing resources, and, on the other, the institutional disinvestment, are on the origin of the precarious condition of the “neighborhoods”.

Construção no Bairro da Boa Esperança, Luanda-

Construção no Bairro da Boa Esperança, Luanda- Casa do bairro Boa Esperança, em Luanda.The gigantic scale of informal housing in Luanda is associated with the continuous growth of the intense production of manufacturing and marketing construction materials and elements, a production that is “informal” therefore invisible on statistics, coexistent with an atrophy of the “formal” industrial production. Likewise, this situation coexists with a generalized difficulty in accessing basic services and infra-structures and with a practically general absence of certainty in the “ownership” of a house, or at least in the right of staying in it or legally negotiating it. This insecurity is a factor in the rise of urban poverty and social exclusion, and the debate on alternative urban politics, adapted to local specificities, is demanded.

Casa do bairro Boa Esperança, em Luanda.The gigantic scale of informal housing in Luanda is associated with the continuous growth of the intense production of manufacturing and marketing construction materials and elements, a production that is “informal” therefore invisible on statistics, coexistent with an atrophy of the “formal” industrial production. Likewise, this situation coexists with a generalized difficulty in accessing basic services and infra-structures and with a practically general absence of certainty in the “ownership” of a house, or at least in the right of staying in it or legally negotiating it. This insecurity is a factor in the rise of urban poverty and social exclusion, and the debate on alternative urban politics, adapted to local specificities, is demanded.

However, if we equate that the area occupied by informal housing largely surpasses the dimension of the remainder areas of the city, just as the population that lives in the “neighborhoods” largely surpasses the rest of the urban population, we perceive that the transformation of these areas must be articulated with the whole city, once it does not seem possible to find structural solutions that are exclusive to one area or another.

For all of this, it is important to talk about the city and to talk about houses and it is good to find so many architects responding to “A House in Luanda” and to know that a large public tries to understand the proposals on display at the exhibition in Lisbon. With great expectation, we attend the exhibition and debate to be held in Luanda.

These are the houses. And if we are to die ourselves,

we are a bit amazed, and a lot, with such architects,

that did not see the unending torrents

of roses, or the permanent waters,

or the sign of eternity spread across the hearts,

rapids.

- What did these architects do of these houses, they who wandered

by the many senses of the months,

saying: here is a house, here another, here another,

so that an order is made, an endurance,

a beauty opposite to the divine force?

Herberto Hélder, in A colher na Boca, Lisboa, Ática, 1961, pp.13

Photos by Cristina Salvador.