Fragments of Reality. Interview with Mário Macilau

Mário Macilau is a photographer (of fragments) of reality. Macilau is a teller of stories and as he narrates he meditates through his images on the social, political and economic environment in his country and in the world, which he explores in its unfeigned naked and raw form. As he states himself, he does not stage or create the photographic moment. His images are instantaneous. He does not seek them, he finds them. Camera in hand, he approaches the countless anonymous people who appear in his work – it is the movement of contemporary man and his relationship with space that interest him. The unadorned body thus becomes the protagonist of the realities he captures. In the instants, there is a silence that presents itself and holds our gaze. This silence allows us to penetrate the intensity of the images and the power of the themes. Macilau’s photos recount distant and specific stories as if at random. Through his images, he reveals to us a little of the World. Of one part of the World.

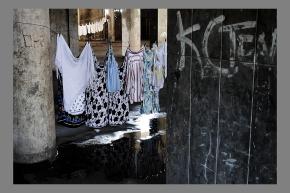

Photo by Mário Macilau.

Photo by Mário Macilau.

Sílvia Vieira [SV]: Mário, how did you first start taking photographs?

Mário Macilau [MM]: I never made a conscious decision to become a photographer, it just happened and I went with it. Through my photography I believe I can at least contribute something to the world; not just because I have talent, but rather because of the characteristics of our space. I use photography as a means of creative and active expression. My life is photography: sixty seconds a minute, sixty minutes an hour, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, thirty days a month and three hundred and sixty-five days a year. I am always thinking about photography and the pictures I’ve taken! I didn’t choose to become a photographer. I don’t know if you can call it fate, in fact I don’t know if I really believe in fate.

SV: Your photographs are always a mirror of your anxieties and reflection on mankind. Would you agree?

MM: I explore the movement of man in time and space. I don’t know what I’m going to photograph tomorrow. My mind functions like a camera.

SV: Most of your work focuses on poverty and hardship. Why? Doesn’t anything else interest you?

MM: That’s a very interesting question. People choose what they want to see and I see people as people and not as poor. I want to talk about my people, those who have no voice; those whose voice has been forgotten.

SV: Before shooting, do you create the situation or do you improvise for the camera?

MM: What interests me is reality. The situations you see in my photographs are captured naturally.

SV: How did the idea for the The Maziones series come about?

MM: I work as a photographic assistant and some people, mainly Europeans, want to take photographs of Mozambique but they need a consultant, or an assistant, or a translator, or a guide. One day, an English photographer wanted to take some pictures on the Costa do Sol, in Maputo, before daybreak. When I arrived, the beach was alive, full of people wearing colourful clothes, crosses, animals, shouting, and I saw what I thought looked like a baptism and took some photographs because it was so interesting. The English photographer said, “Why are you photographing that? Nobody’s going to be interested!” But for me that moment showed another side of life. I don’t take photos because I think people are going to like them but to give people who have little voice a chance to speak out.

SV: Did you try to talk to them?

MM: It is essential for me to establish a relationship with the people I come in contact with. They become a part of me and I become a part of them… Then I take their picture, juggling the interplay between light and the lens.

SV: Many critics and scholars regard photography as something fictional, as the photographer’s interpretation of the reality s/he observes through the lens. Would you agree?

MM: It is my eye on reality… I use photography as a means of social intervention. I’m interested in exploring the reality of space and its movements. It reminds me of what Steve McCurry once said: “Many of us are in a position to help others, but few of us are aware of what we can do – or what a difference our contribution can make. I hope my photographs help people become more informed.” I explore photography naturally… I want to create message after message!

Photo by Mário Macilau.

Photo by Mário Macilau. Photo by Mário Macilau.

Photo by Mário Macilau.

SV: What was it like going to Makoko in Lagos, Nigeria, where you shot the Wood Work series?

MM: My trip to Nigeria was great but at the same time very difficult, mainly because of the “area boys” (also known as “agberos”). Lots of neighbourhoods of Lagos are controlled by these gangs of adolescents who roam the streets extorting money from people and selling drugs and other services. But before I left for Nigeria I did some research on what I wanted to do and so it was easier to come up with some strategies. I dressed in rags, soiled my camera and met and talked to a lot of people so as to make friends, including some local area chiefs. And after that everything went smoothly… The most important thing is to show character and to be nice to people. I’ve met a lot of photographers who like to think they’re special… I see that attitude as an obstacle to working with people in general.

SV: Do you find the situations you photograph troubling?

MM: It’s not the situations I photograph that affect me. It’s what I’ve seen in general. The world keeps moving everyday and I’ve analysed this movement to try to understand where it’s going. We lead strange lives; the majority of people don’t seem to care what happens to others, or to the world as a whole. Man is full of hatred. Racial hatred and political and economic struggle. Have you noticed just how different we are? Have you ever imagined the difference that one US dollar can make to someone’s life? In my photos I look for lives, beautiful soulful faces. I like to show the world the faces of people who aren’t usually seen.

SV: In some series you use black & white and in others colour. How do you decide?

MM: We think about things in different ways. When I think about the past, I think in grey. Things change, places change… Now I think more in colour, I see things full of life.

SV: So when you photographed the Wood Work series in Nigeria in black & white was it because it took you back to the past?

MM: Yes. I photographed those people in Nigeria because they live in miserable conditions. They have absolutely nothing, not even a piece of land. I looked and photographed in black & white – it was just spontaneous.

SV: What does the “other” mean to you?

MM: What would the “other” be without me, or what would I be without the “other”? Man is what he is because there is another man.

SV: The titles you give your photographs are objective and direct. Don’t you believe in the power of words?

MM: I believe in the power of words, but I also believe in the opposite, that one picture is worth a thousand words. To me, photography is the poetry of immobility. It is through photography that instants reveal their true selves. It is through photography that people learn something about realities that they had never even imagined. It is through my photographs that I construct verses and stanzas; through the way the light reflects… I tell stories which at times are very familiar to us but which we can’t see. Photography allows us to perceive and reflect on reality more closely.

Photo by Mário Macilau.

Photo by Mário Macilau.

SV: In some photographs, you adopt the role of a voyeur. Do you agree?

MM: Not at all. I never take photographs at a distance because I like to create a relationship between the camera and the people I shoot. I don’t steal when I photograph. I talk to the people, enter into their lives and forget about my own. I take close-ups, using a 16-35 mm or 18-55 mm wide-angle lens, and on rare occasions a 70-105 mm lens (only when I want to cause an effect on the sides and in the background).

SV: What criteria did you use to select the photographs for this exhibition and catalogue?

MM: I made a very personal selection of some of my work, based above all on the message. They are images of situations that are largely unknown. I want people to look and think about them. In the first part of the catalogue, I’ve included a series I did on the Zionists (popularly known as the “Maziones”), members of a traditional religion of some importance in Mozambique. Most of its members live in rural areas or on the outskirts of large cities. In general, they don’t have access to hospitals and that is why they invoke the holy spirit and the divine cure through the actions of miracles. They perform ceremonies such as baptisms and practice rituals involving animal sacrifices. The Zionist Church is based around the figure of the pastor (mifundisi, in Tsonga), who has various talents and presides at ceremonies. The second part of the catalogue consists of photographs taken in Makoko in Nigeria, a slum in Yaba, in the suburbs of Lagos. In this oil-rich country, a plot of land can cost millions of dollars. So large numbers of homeless and poor have created a community of wooden and corrugated zinc huts on stilts in the sea. The polluted water is their only means of communication and boats are their sole means of transport. Their lives depend on water and wood. But logging and water pollution cause serious environmental damage, mainly due to the systematic felling of trees. In general, I also focused a lot on specific technical aspects. The light is very important in this context.

Photo by Mário Macilau.

Photo by Mário Macilau.

Photo by Mário Macilau.

Photo by Mário Macilau.

SV: How do you see your future as an artist?

MM: I can’t say. To be honest, I’m more concerned about the present than the future and what really matters to me is my work. Despite all the problems that crop up from time to time, I’ve put everything into it. As the old saying goes: “You reap what you sow.”

SV: Is there a central idea in your life?

MM: We are not truly alive when we live only for ourselves; we are who we are because of others. Sometimes we sense that we should do something like plant a tree, even if we know that we will never eat its fruit or sit in its shade. Or we discover that we should devote ourselves to something more than just our own petty problems, and rebuild the ruins that we see around us everywhere. It is at times like these that we grow as people. And that we are true to ourselves as never before.

Vilamoura, 15 November 2010

Published in the catalogue of the exhibition BES Photo 2011, Co-edition Banco Espírito Santo / Museu Colecção Berardo, Lisbon, 2011.