Identities, causes and effects

Délio Jasse work can be interpreted under the somewhat complex view of the post colonial speeches, in the sense that his images emanate a quality of alterity, which gives them identity. However this simplification can be limiting if it becomes dissonant with the artistic speech where his images belong, obviously.

In post colonial studies, as stated by Homi K. Bhabha in “A Questão Outra” (1994), the images of the “other’s” figure are always sabotaged by a stereotype of normality imposed by the dominating powers producing the resistance, domination or dependence of the colonized people under the concept of “fetish”. The author adds, “this fetish or stereotype allows an identity based not only on control and pleasure but also on anxiety and defense, since it is a form of multiple belief and represents a contradiction in its capacity of recognizing difference and denial.” The argument concerning post colonial reality becomes harsher and, without focusing too much on this issue, the opinions become ambivalent in the sense that they become derogatory (Judith Butler, Gender Trouble, 1990), meaning that the way they are staged in diverse ways in certain moments lead to the conclusion that the speeches\narratives cause fracture and are distorted by their authors and\or readers.

However, the images produced by Délio Jasse are not pre-determined by an agenda but are really impregnated with the plurality that characterizes the artistic speech. This type of speech, by principle, will not be interested in determining a political vision; it will be mainly interested in changing the existing stereotypes, following a journalistic or documental approach.

However, the images produced by Délio Jasse are not pre-determined by an agenda but are really impregnated with the plurality that characterizes the artistic speech. This type of speech, by principle, will not be interested in determining a political vision; it will be mainly interested in changing the existing stereotypes, following a journalistic or documental approach.

Photography is a process that documents a fake reality, since it freezes a certain moment and a specific point of view. In this way, the nature of the image the artist presents should be unconditionally questioned and its veracity doubted. The images that are found either in the street, thrown in the garbage, found in markets or thrift shops are intimately related to a subconscious identified as African. According to Edward W. Said in ” Reconsiderando a Teoria Itinerante” (1994), “the subsequent versions of the theory cannot replicate their original power since the situation has eased and changed, the theory degraded and was tamed, becoming a relatively domesticated substitute of the thing itself, which aimed for, in the work being analyzed, political change.” If the theory can no longer – if ever it could – reach truth concerning the issues and the world, then the images that have as reference other images, as it happens with artistic images, obviate that these versions can be more real about a certain previous event or about the identity of the subject being represented.

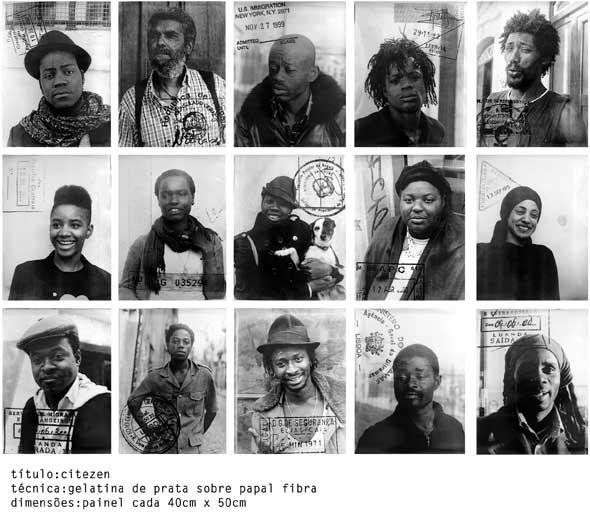

Délio Jasse’s pictures are conventional portraits, which reveal the identity of its subjects, echoing physical or biological anthropology studies made popular in the beginning of the 20th century and fed by the official labeling stamps. However, reality is undermined by the intoxicating photographic technique used by the artist. In an almost baroque way, the photographs are printed in drawing paper where the image conveys a false time, as if trying to salvage the originality of a time passed – “this-was”, Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida (1980). This effect seems to want to destabilize the identity or the image of the person being portrayed, as if questioning the veracity of the images being shown, as well as the document they could become.

In a short survey of news pieces concerning Angola in the 60’s, gathered from a reference newspaper of a Salazar-bound Portugal, it is possible not only to come to conclusions rendering the way these images were constructed but also to reveal the “myth creating addiction” associated to these same images, taking place in the great metropolis and in this way satirizing the perspective on these “others.”

The journalist Greg Connoley writes that “Luanda is the mirror of the proud assertion held by the Portuguese that there is no longer racial discrimination in any part of its territory. (…) The Canadian journalist observes that in Angola, not only black and white children play and study together but also the mixed race people, who can be seen everywhere in high percentages, are the uncontestable proof of the absolute inexistence of racial prejudice. (…) Connoley finally quotes recent declarations from the Portuguese foreign affairs minister Dr. Francisco Nogueira, emphasizing the following statement: “in Brazil, we, Portuguese, helped to built a magnificent interracial nation. If we are allowed to we will do the same in Africa.” DN (Diário de Notícias newspaper) December 13th 1962, p.1.

Henriette Oboussier, investigator from the University of Hamburg who studied the serpent-monster from Curato River says: “only here in this blessed land that the Portuguese were able to develop in a way that amazes us, you can see the natural and affable way the natives are treated. This fact assures us of a humanistic evolution lacking any imposing ethnicity. (…) The Portuguese individual, father and brother to half the world have created in this blessed land a racial fraternity which is the glory of humanity.” DN August 4th 1963, p.4.

A New York Times journalist affirms that Luanda “is on the way of becoming one of the biggest tourist centers of Austral Africa, in spite of the action of the guerrilla which began 9 years ago in Angola.” DN 10 de Fevereiro de 1970, p.1.

According to the facts mentioned above, bearing in mind that the war in Angola lasted from 1961 to 2002 and considering the scarcity of Portuguese post colonial studies and particularly from the analysis of journalistic and official speeches about the ex-colonies, one can see that this documental narrative was hardly related to any truthful image that reflected that particular territory’s reality and one can consider, precisely due to that reason that the speech was appropriated and controlled by the political power installed.

In the way that the work of Délio Jasse questions the factuality of the documents and images it presents, in the pertinence attached to the discussion around the constant quest of cause and effect belonging to the stereotype of those incongruent images, one can affirm that the speech presented has an artistic character tending towards the deconstruction and demystification of the images and the speeches produced. In this way the work of the artist is imposed, not as dogma and absolute truth but with pertinent questioning and doubt. The images produced in a third version, after the original image is removed from reality, provoke a plurality of identities belonging to the portrayed individual, in this way originating new stories and new routes. The pertinence will be political in the sense it undermines the hegemonic models that have been instituted – racial, social, sexual – allowing one to travel with no stereotypes to an encounter or reencounter, if not true at least sincere and honest with a certain people and their land.

Lisbon, July 2010