Urban Africa: Pan-African View

David Adjaye1, one of the leading architects from his generation, living between London and New York, returned to Lisbon. ‘Urban Africa - A Photographic Journey’ was the reason why. This exhibition, recently launched at the Black Pavilion of Lisbon City Hall Museum, is a photographic tour but also a retrospective of memories from an architect who never left Africa.

Born in 1966, in Tanzania, from a family of diplomats, he was soon forced to understand the inevitability of travelling, the need to readapt and redefine oneself. Nevertheless, the nomad lifestyle didn’t break his strong relation with the African continent. His work confirms his deep relationship with its landscapes and its places. In Urban Africa (and also in this conversation) David shares his panoramic view of this vast territory and his – spoken – will to live there again.

Cortesia de Adjaye Associates / Courtesy Adjaye Associates

Cortesia de Adjaye Associates / Courtesy Adjaye Associates

Lisbon again.

Yes, nice to be back.

This time to attend the opening of Urban Africa. Is this photographic voyage a kind of solitary return to your childhood memories? Why now?

Undoubtedly, that’s how it started, innocently, without premeditated agenda. A quest to fill in the gaps of certain memories. But then… within ten, twelve countries, it became very clear to me that when showing it to other people, people that I thought would know about the subject… that actually there was very little knowledge about urbanism in the continent. I ended up doing a show in Harvard, in 2003, literally a third of the way through the project, I was asked to show my work, but I said - How about showing some research that I’ve been doing? And Toshiko Mori was the director and she said - Absolutely, what do you want to show? I said - I want to show you twelve African cities… I’d only been to fifteen then, I’d show twelve and the research on it, and we’d see the reaction o the public. We displayed it in the main hall at Harvard, and it was a huge revelation to a lot of people… literally, it was off the radar, and what was chocking for people was that they didn’t realize that the discourse of modernity, the discourse of post-modernity, the discourse of post-development also has it’s residue in Africa, and it’s sort of surprising to me that people didn’t think that, but there it was… all the ideas that were being discussed, nobody had systematically sought to understand the relationship of these ideas… in the context of this continent.

You grew up all over the world and then stopped in Britain, yet you carry Africa more strongly with you than if you had lived there. Where does this come from?

I blame my mum! (laughs) because we travelled so much, my parents were very sensitive to the idea that we came from a certain culture and a certain identity. So that was always very clear at home. At home we were ghanaian kids as the others… we spoke the language, we had the food… That was the stability, this identity. So, in a weird way, event though I don’t spend that much time in Ghana, I know a lot through my parents and family, who always surrounded me. We were able to go out into the world but always know that we could retreat into the safety of our family unity and identity. It wasn’t a case of dissolving into the world.

Abidjan, Costa do Marfim. fotografia de David Adjaye

Abidjan, Costa do Marfim. fotografia de David Adjaye Bamako, Mali. fotografia de David Adjaye

Bamako, Mali. fotografia de David Adjaye

Is architecture different in Africa? How do you think that architecture is perceived?

I don’t think that the built fact is different, necessarily. But I do think that the inhabitation and the translation are completely different. I think that this is the thing to understand in Africa. There is built fact… in the way in which we understand empirically hot to put together a building, but the use of the building, and the way in which people understand the meaning of the building are very different. And society and context play very heavily in that… because there is a residue of a kind of image of architecture, which is deposited in Africa, which people think means there’s a certain lifestyle that goes with that territory… but it’s not necessarily. There’s a very ambiguous lived life, and I argue very strongly to be determined through understanding climate and region. Because the climatic conditions are so extreme, these are not moderate temperatures, harsh. Even the savannah of the Sahel, which is less than the desert, is still really intense. The savannah is incredible, it’s this incredible horizontal plain, with this incredible vegetation…. really a culture of fields, not really of settlements, but you see places like Nairobi, which is fascinating, flat mass… and then you see the heart of the continent is the tropical forest, the deep, west and central African belt, and in a way that it the luscious part of the continent, because that’s were the rivers really are…

It makes all the difference…

Totally! That’s also were the cultures are very strong, because the rivers and agriculture make a strong cultural… voilà! It becomes very obvious when go through it like an anthropologist, it’s very straight… The place still influences the object. You have to really understand the sensitivity and then you start to understand what these images mean… this was not trying to talk about architecture as the emphatic object, but to try talk of architecture as fragments within the composition of the city. Architecture that is only understood by understanding what the place is. You get hints in the photographs, but you don’t fully know, you’re being asked to enquire, I want you to inquire more: - Why does this look familiar but is not?

Tunis, Tunísia. fotografia de David Adjaye

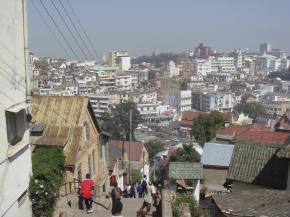

Tunis, Tunísia. fotografia de David Adjaye Antananarivo, Madagascar. fotografia de David Adjaye

Antananarivo, Madagascar. fotografia de David Adjaye

In more detail, what do you think you have brought from Africa into the western architecture world?

I think that I have a very different discourse about the notion of habitation and the notion of publicness. I think that, even without me realising it, during my research I’ve become very conscious of my own practices, I realise that I always have a desire to express a certain kind of publicness… an overt publicness, even when it’s not there, and I think that’s a very African sensibility, this idea of the open, public… to see. Not to hide, to see! I think that that’s present in my work. Also – maybe this is African, I’m not sure – I have a certain delight in the potential of material… there are lots of sensibilities of that, but I think … when I look at certain shantytowns, I’m chocked at the delight of materiality, it blows me away… that everything is possible, in a new configuration, to make a new composition… it’s powerful to me. Really, really powerful to me. It is a kind of sensibility about the opportunity of material which maybe comes from the continent: a desire to find something in every potential material.

From your words, concerning also this exhibition - far from a mere selection of photographs - you get a sense that you’ve channelled a great deal of energy into it…

A ton!

Almost as if it were an architecture project… Is it true?

It is an architecture project! Because in a way, my architecture, more and more… I realise that it’s relationship is predicated on the understanding of the city, wherever the city may be. To understand my projects you have to understand where they are, otherwise you’re just saying - Huuummm… it’s ok! I’m not interested in the fetichisation of the object autonomous to the context. Some people are, it’s fine… but it’s not the thing that predicates me. The moves that I make and the strategies require an ability to be part of the place. Not just to pass through. If you pass through my buildings you might miss them! But if you use my buildings within a city you will…

I see you as a ‘perfectionist’… your work speaks for itself. Exhaustive research labs for houses, and more recently, for public buildings… I recognise a great quality in this attitude. To seek knowledge and control to then be able to play. Did you also have fun during these African incursions?

Completely! And the irony of it is… I had so many friends ho said - Can I come with you??! - And I said no! It was like… a space for me, and… I was actually a little bit sad, when I finished… - Oh my God, I’ve done it!… I’ve been to every single one.

You also remind me of Niemeyer, who you’ve actually interviewed a few years ago, for BBC…

He’s a hero.

In his reflection on the importance of drawing, when he says that architects must know how to draw, to loosen and untangle their hand to be able to work. Looking around in the exhibition, is it correct to establish a parallel between the digital camera and the sketchbook that Niemeyer is talking about?

Absolutely. I think you can make that assumption, because in a way these are sketches, these are very much sketches, and the composition it sets up is sketch. I love the digital camera for that, I think that it is the pencil of the XXI century, it is a kind of ability to re-look and look again, to zoom in and zoom out, study again… and to be free, with things that sometimes you would not want to look at. I think the digital camera is great like that, it forces you to take a look at it, even when it’s not personally what you like… and think about it!

Gaborone, Botswana. fotografia de David Adjaye

Gaborone, Botswana. fotografia de David Adjaye

These photographs are full of life, people, more than only architecture, which I find very interesting.

Yes, in fact.

Somewhere I read that taxi drivers were your great allies!

They were my biggest fans! When I started going to Africa, in the first few times I got a guide, I very quickly realised that the guides were really narrow-minded, they had a picture of their city that they wanted to present to you, not the reality of the city. They had an image and they anted to curate you through that image, and then let you go home. It was too much for me, I couldn’t stand that way of curation, it was too authored for me. And also, I’m not interested in the propaganda, I wasn’t there to be spelled … that Africa is some beautiful place for anyone. I know some Africans were shocked… that I was visiting… poor housing. I do not make any judgements because I see a poor house; I can see a poor house in San Francisco. It’s not the point. I found taxi drivers to be completely not interested, or not able to be so emphatic… especially normal taxi drivers, I would go to their houses, have soup with them…

Is it a surprising informality as well?

Exactly. Beautifully said. The start with them would always be - Where do you want to go?… there was always this little moment, like a little love affair… I’d chose one, go for two minutes, see if we can make basic communication understanding, and I’d say - Put the clock on, I want you to show me every part of the city, every part that you know, the full… to the place where nothing happens, to the place that’s most dangerous, every place. I don’t car how long it takes; you can take a day, two days, three days, one hour… as you wish. And it’s amazing, once you do that, first they start to whiz you around, then they start taking you, and before you know, you’ve done the patterns of city. You what they do with tourists, the patterns for the people they take form work to work, then the weekend journeys… you do the patterns that are inherited in the city, you can almost map them in your mind. He goes through his methods, his routes, and before you know it, naturally it comes to its exhausted end, because you start to see everything again. Then he starts going round and round and you go - So I guess that’s the city, then! After that I say I want to go back to this area and I photograph the area, and I rarely come outside, I don’t like to stand outside either, I don’t like to compose too much. We’d stop at the places and just shoot. If it were difficult, then I’d go out and shoot. But I try to people not to see me photographing.

Nouakchott, Mauritânia. fotografia de David Adjaye

Nouakchott, Mauritânia. fotografia de David Adjaye

I understand. ‘Present’ without interfering…

I wanted the life to be just going on, and for me to be really discreet with that. Because whenever you stand outside, the place change… everything changes, it’s like… reality changes. So, they were great, it allowed me a certain informality and a certain distance. Because, in a way, clearly I am the author, but I wanted to feel un-authored… de-authored… somehow, matter, like some kind of molecule.

And today… What do you see as your connection to Africa? Purely professional, emotional? Is Africa in your agenda?

My problem is that I can’t resist the continent, it keeps pulling me. So I’m now, after fifteen years of working in the world, I’m finally working in Africa. I’ve finally succumbed! But I’ve had a chance, the economies are growing. Where my family is from, in West Africa, it’s booming. In a way, I feel like there’s an opportunity for me to work in the continent, after finishing this research, which took teen years of my life, I feel like I have a pan-African view, which is a very useful piece of data in my mind. I am now working in West Africa and South Africa, and I hope to have an office there… and who knows, maybe having another home! I live in the world!

Thank you David.

Let me share with you… I am very jealous… this must have been a tremendous experience. How I would have loved to do this exhibition… Congratulations and welcome to Lisbon!

(laughs)

- 1. DAVID ADJAYE Biography David Adjaye is now recognised as one of the leading architects of his generation. Having developed a reputation as an architect with an artist’s sensibility and vision, an ingenious use of materials, bespoke design and an ability to sculpt and showcase light Adjaye’s work has engendered high regard from both the architectural community and the wider public. He established his studio, Adjaye Associates, in June 2000 and has since gone on to win a number of prestigious commissions. Projects have been diverse in scale, audience and geography; collaborations with artists including Chris Ofili and Olafur Eliasson, exhibition design, temporary pavilions and private homes both in the UK and U.S. More recently, major art centres and important public buildings across London, Oslo and Denver have demonstrated David’s considered approach to understanding the needs of the inhabitants of each space and a respect for the integration of the buildings within their natural environment. These are ideas, which are based on the premise of quality of life of society in the cities. David Adjaye understands his status as a role model for young people and lectures frequently. He was the Kenzo Tange Professor in Architecture at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design in 2007 and taught at Princeton University in 2008. Previously a unit tutor at the Architectural Association, David was also a lecturer at the Royal College of Art where he received his MA in architecture in 1993. That same year he was awarded the RIBA First Prize Bronze Medal. Following this, he trained at David Chipperfield Architects and then Eduardo Souto de Moura Architects in Oporto. His Idea Stores in Crisp Street and Whitechapel won several prizes and in 2005 David Adjaye received a RIBA Building Award. Adjaye’s latest project was SKOLKOVO, the Moscow School of Management; it was concluded in 2010 and has achieved great recognition. David Adjaye now leads the FAB team, Freelon Adjaye Bond/Smith Group, responsible for the project of the new National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington DC, which will open in 2015. In May 2005, Thames & Hudson published David’s first book, ‘David Adjaye Houses: Recycling, Reconfiguring, Rebuilding’, which was distributed worldwide. In January 2006, the Whitechapel Gallery in London hosted the studio’s first exhibition ‘David Adjaye: Making Public Buildings’, which was accompanied by a book of the same name. The exhibition then toured to the Netherlands Architecture Institute, Maastricht, Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, SCAD Savannah and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Denver. David has co-presented two television series of Dreamspaces for the BBC, a six-part series on contemporary architecture, and hosted two BBC radio programmes; the first featured an interview with Oscar Niemeyer and the second with Charles Correa. In June 2005 he presented the TV programme ‘Building Africa: Architecture of a Continent’. Following on from this he pursued a personal project to document each of Africa’s capital cities, culminating in the 2010 exhibition ‘Urban Africa – A photographic journey by David Adjaye’ presented for the first time at the Design Museum, London. The book followed in late 2010. In June 2007, David was awarded an OBE for services to architecture. He received an honorary doctorate of the arts from the University of East London in November 2007. www.adjaye.com