The Colonial Unconscious

It’s a common place to say that the memory production drags with it, inevitably and concomitantly, the forgetfulness production. There are many ways of forgetfulness, the most insidious of which is, undoubtedly, the memory erasure, the past rewriting as part of a deliberated strategy of intervention in the present. The most extreme way of this erasure is the denialism or the revisionism, for example, the denial of the Holocaust, that, for good reasons, several countries legislation refers to the criminal sphere. There are, however, other ways of forgetfulness, much more harmless, but whose consequences are, equally, deeply negatives, since they deprive us of justice instruments and shape our present in an impoverishing and excluding way. One of those forms, of manifest relevance in the current Portuguese public debate, is determined by what I call the colonial unconscious.

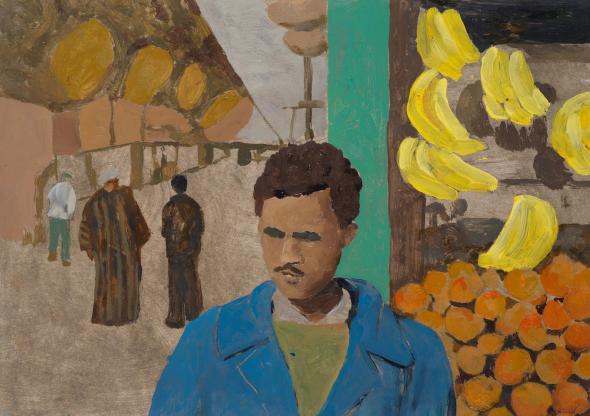

Mercado | Eugénia Mussa | 2020

Mercado | Eugénia Mussa | 2020

The history of the different European colonialisms is a diverse history, with different routes in its historical specificity, but which converge on fundamental points. One of those points is based on what we can call the colonial difference, that is, one ideologic construction according to which exists one fundamental difference, one key dividing line between the European settler and the colonized man, whose most relevant indicator is the race concept, but which can be also defined based on other several markers, and that legitimates the exercise of power and, if necessary, of the violence against the colonized, including of the epistemic violence, that only consents the narrative of the colonizer and shuts down completely what could be the narrative of the colonized.

The concept of difference so established, basically shaped according to the dialectic of the lord and servant, settled down deeply in the European unconscious, and even defines the European relations under the terms of a North-South division, as yet recently was well exemplified by the biased vision on part of German or Dutch political leaders, from an South European as inhabited by people without work ethic, one vision, in fact, entirely coincident with the vision of the African developed in the processes of colonization.

Throughout the 19th century, especially the second half, with the effective occupation of the African lands by the European powers, the colonial project has become entirely confused with the national and imperial projects on the point of consolidation. The power of national and colonial narratives developed in this context extends until our present and touches on repeatedly in the form of common sense supposedly undeniable.

Portugal isn’t exception : fundamentally, the patriotic speech that has become hegemonic in the last 19th decades and found the apogee in the crises of the English “Ultimatum”, defining the colonial possession (the vocation) as an indissociable component from a national ambition, isn’t structurally very different from what will become the New State’s speech. This, however, in particular through the instrumentalization of the Portuguese – tropical theses, was particularly successful in the consolidation of a benevolent narrative based on the concept of a whole national that covered the “overseas provinces” and presented itself as natural progression of an historical continuum in which the greatness and the nation exceptionality were an uncontroversial fact.

Almost fifty years after the 25th April, it’s manifest that this successful narrative continues to be interiorized even to the most recent generations and it remains strongly latent, ready to come to light at the first opportunity. Marked in the colonial unconscious, which isn’t by chance that the sphere of affirmation of this narrative is ruled first and foremost by emotional dimension, making it so much harder to submit to the criticism, specially the historic one. Two recent examples give a full testimony of this and, not being particularly relevant, become very significant as symptoms of the way certain forms of memory worship perpetuate the forgetfulness logics firmly inscribed in the Portuguese and European colonial unconscious.

Much has been already written about the question of the coats of arms preservation drawn in the Praça do Comércio’s plant cover in Lisbon representing, among other entities, the “overseas provinces”. It doesn’t matter that historical criticism, for example, of Francisco Bethencourt and Kirti Chaudhuri in his História da expansão portuguesa, has long shown how these coats of arms, added to the design of the square as part of the 11th National Exhibition of Floriculture, which took place in 1961, are spurious relatively to the initial urbanistic project and formed an instrument allegedly memorialist to affirm, at a time when, precisely, the “Empire” was entering its final crisis, the idea of national continuity, the same that, at short notice, would serve as a legitimization to the Colonial War. The public clamour of outrage on behalf of the coat of arms permanency, materialized in a petition with thousands of signatures and in positions taken by graduated figures hardly finds rational explanation and only can be analysed considering the persistence of an unconscious colonial that I’ve been referring to.

Particularly significant, in my view, it’s a text from the landscape architect Cristina Castel-Branco published in the newspaper Público on the last 20th February. To the author, the coat of arms preservation is justified by the “link to place” (it isn’t clear from whom – the users of the square, including, perhaps, the masses of tourist who, in normal times, make up the majority of these users? From the Lisbon people? From the Portuguese in general?), and by the “communitarian effusion” underlying to that link – without letting it out, equally, know what community is after all. In any moment of the text exists any reflexion about the coats of arms meaning, treated simply as if they were a patrimonial element like any other. Thus, defined the “naturalness” of the coat arms presence that, apparently, according with this logic, there shall remain until the end under penalty for serious amputation of our collective being-, everything transforms then in a simple technic problem, easily resoluble, in the authors’ point of view, if it passes from the plant element to the mineral, inscribing the coats of arms in the form of Portuguese sidewalk.

Does that mean the author or the same ones who equally defend the symbolic importance of the coats of arms are motivated by an impenitent colonialism nostalgia? Surely that, in some cases, this will be the truth, but nothing authorises to generalize, on the contrary. There is no doubt that they are basing themselves on, can be said instinctively, an essentialist and static perception of a supposed community and on a thoughtfulness acceptance of a problematic historical continuity, which lead to the disconnection of “heritage” from the context that gives it meaning. The inability to assume that the societies change and go through rupture moments that, over time, lead them to stop recognizing themselves in any kind of memorialist unanimity perpetuate a narrative purely ideologic that shuts down and excludes any alternative memories.

A second recent case, very different, is the posthumous tributes to Marcelino da Mata. The facts are known and corroborated, namely by Mário Cláudio, with an extensive and direct knowledge of cause: Marcelino da Mata, African command serving the Portuguese army, was perpetrated author of war crimes and was widely known for his total absence of scruples in the conduct of acts of war and , in particular, in the unhuman and homicide treatment of prisoners. There is clearly, in this aspect, the full responsibility of the Portuguese State. Since the New State never acknowledged that was fighting a war, always referring to as simply police actions and order maintenance against “terrorists” in the pay of foreign powers, had also dispensed from any obedience to the Geneva convention. From this point of view, Marcelino de Mata was only particularly cruel executor of a military strategy in which he integrated with special efficiency. The exaltation of his “individual courage and bravery” in the official praise of which he was posthumously object – as if courage and bravery were values in himself and there was no need to ask in what context and for what purpose were demonstrated – it’s just a moment especially shocking of the silence continuum that continues to involve the colonial past.

The multitude of comments that flooded the social media and the comments box of the newspapers to associate to the exaltation of Marcelino Mata’s path as an patriotic example and a nation value was well illustrative of how, for the unconscious colonial, the victims’ memory doesn’t have right to exist so that isn’t called into question the legitimacy of the dominant national narrative. Also, among the paladins of the glorious pretendedly memory of a war criminal there aren’t, certainly, not only hardened colonialists. From extreme-right militants, passing by Colonial War’s veterans, some of them perhaps understand that only can give meaning to their lives if they give purpose to their forced participation in an absurd war, even citizens with personal and very diverse political positions, there will be of everything. But also here, especially in the way it has been repeatedly brandished, by the way of the argument, the rhetorical figure of the “hero”, of the national hero, reveals itself blatantly the memory selectivity and the way how an apparent gesture of defence of memory constitutes a brutal gesture of silencing. We know, from other historical examples, such as, for example, the Algeria War’s memory in France, that, as rule, takes a long time for a dispassionate confrontation with a past in several aspects traumatic. But this confrontation is an ethic and political imperative and it’s a justice imperative, that justice which is claimed by the thunderous silence of the excluded, before which the indifference, the forgetfulness or the simple ignorance aren’t admissible.

MEMOIRS is funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Community Framework Programme for Research & Innovation (No. 648624).

MAPS - Post European Memory: a post-colonial cartography is funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT - PTDC/LLT-OUT/7036/2020). The projects is based at the Center for Social Studies (CES) at the University of Coimbra.