Why Is Mainstream International Relations Blind to Racism?

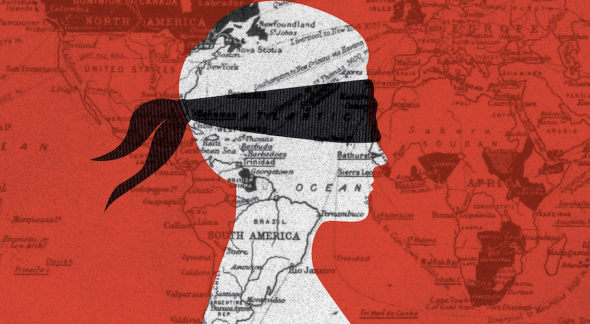

Foreign Policy Illustration/1897 Map of the British Empire/Getty ImagesIgnoring the central role of race and colonialism in world affairs precludes an accurate understanding of the modern state system.

Foreign Policy Illustration/1897 Map of the British Empire/Getty ImagesIgnoring the central role of race and colonialism in world affairs precludes an accurate understanding of the modern state system.

Worldwide protests against police racism and brutality and the toppling of statues commemorating white supremacists have led to a public reckoning in the United States and many other countries—forcing citizens and governments to confront the historical legacy of systemic racism and the enduring inequalities it has created. A similar reckoning is long overdue within the academic discipline of international relations (IR).

Beginning with its creation as an academic discipline, mainstream IR has not been entirely honest about its ideological or geographic origins. It has largely erased non-Western history and thought from its canon and has failed to address the central role of colonialism and decolonization in creating the contemporary international order.

Foreign Policy asked nine leading thinkers in the field how IR has fallen short and how the research, teaching, and practice of it must change.

Forget Westphalia. The Modern State Was Born From Colonialism.

By Gurminder K. Bhambra, a professor of postcolonial and decolonial studies in the Department of International Relations at the University of Sussex. She is the author of Rethinking Modernity: Postcolonialism and the Sociological Imagination and Connected Sociologies.

Matters of race are usually addressed as domestic issues—that is, as questions of identity or in terms of stratification (the differential distribution of rewards and resources within a country). While both of these categories of analysis are of fundamental importance, they often neglect the international processes through which race and racial differences have also been produced.

The history of the modern state system, as it is often taught, focuses on the impact of the American and French Revolutions in the late 18th century. However, this is precisely the period of colonial expansion and settlement that saw some European states consolidate their domination over other parts of the world and over their populations, who came to be represented in racialized terms.

This external domination is rarely described or theorized as a constitutive aspect of the so-called modern state—which, then, is imperial as much as national. The racialized hierarchies of empire defined the broader polity beyond the nation-state and, after decolonization, have continued to construct inequalities of citizenship within states that have only recently become national.

Britain, for example, did not distinguish among the members of its imperial polity when legislating for citizenship in 1948, with common citizenship available for those in the U.K. and in its colonies. As empire receded, entitlement to citizenship narrowed along racial lines. In light of the subsequent so-called hostile environment policies, those who had moved legitimately to the U.K. from the nonwhite Commonwealth were required to demonstrate their entitlement to citizenship and, if they could not, were in many cases deported in what has come to be known as the Windrush scandal.

Race isn’t a factor that enters so-called nation-states from the outside. Rather, they are racialized from the very moment of their emergence as imperial polities and continue to reproduce racialized hierarchies to this day. Scholars and practitioners of international relations must take seriously the colonial histories that were constitutive of the formation of modern states. A failure to do so not only is an intellectual error but also has profound consequences for the nature and possibilities of politics—including the politics of race—in the present.

Africa Isn’t Rising. It Has Always Been at the Center of Global Politics.

By Yolande Bouka, an assistant professor in the political studies department at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario.

If the field of international relations is truly committed to wrestling with the history of racialized international political analysis and practices, it must first come to terms with the erasure of the roles non-Western political actors and societies have played in shaping global affairs. In the case of Africa, challenging that erasure also means questioning the recent “Africa rising” narrative, which seems to imply that Africa was, until very recently, at the margins of the global economy and politics.

From Mansa Musa’s role in Cairo’s decade-long economic crisis in the 14th century to a key 1764 battle near Atakpame, in what is present-day Togo—in which the Ashanti Empire suffered a devasting defeat against the Dahomey Kingdom and the Oyo Empire, leading to shifts in Ashanti foreign policy—it is clear that many pre-colonial African polities’ activities had important international implications.

Similarly, centuries of economic and diplomatic exchanges between China and various African polities before colonialism, and Africa’s role during both world wars, demonstrate the continent’s long-standing and well-documented relevance in world affairs.

Challenging racist analyses in the discipline also means being more curious about African actors’ agency at various levels of analysis. State-centric approaches tend to focus on state capacities and failures and ordinary Africans merely as bodies to be acted on and moved like pawns on a global chessboard, which obscures how their strategies, engagement, and resistance shape flows of power in the international system.

Today, any discussion about the so-called “new scramble for Africa”—in which countries like the United States, China, and Russia compete for market share, resources, and influence on the continent—divorced from a proper examination of local, national, and regional interests, power dynamics, norms, and practices will yield poor academic and foreign-policy analysis.

To properly understand the central role Africa has played and will continue to play in future debates about international relations and in world affairs, the field needs to remedy the African archive’s erasure and get comfortable looking race in the face.

Liberalism Didn’t Create Modern Democracy. It Emerged From the Activism of the Oppressed.

By Randolph B. Persaud, an associate professor of international relations at American University.

The last weekend of June closed off with some history-making events in three different institutions. In academia, Woodrow Wilson’s name was removed from the School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University. In government, the Mississippi Legislature voted to remove the battle flag of the Confederacy from their own state flag. And in entertainment, a concerted effort got going to remove the name and likeness of the famed actor John Wayne from the airport in Orange County, California. These developments reveal a great deal about the domestic social order in the United States, and world order, more broadly. They also have resonances for IR theory, if indeed IR theorists were more attuned to the multitude of exceptions that accompanied foundational liberalism.

The core elements of what I shall call Euroliberalism include but are not limited to the right to life, liberty, and property; equality before the law regardless of any attribute or marker of identity; and toleration based on reason. In The Great Delusion, John Mearsheimer fleshes out the varieties of liberalism relevant to IR theory—as well as the catalogue of exceptions, many of them based on racism and civilizational bias.

Notwithstanding the brilliant disquisitions of European philosophers and pronouncements of presidents and prime ministers, democratic governance from India to South Africa to the American South has emerged principally through the activism and agency of subaltern populations—those subjected to the hegemony of a more powerful class or group, especially colonial subjects, and those victimized by anti-Black racism and other forms of discrimination.

The killing of George Floyd and the movement for change that it has sparked mark a historical moment in democratizing democracy. Police forces—a key institution in liberal democracies—are now being pushed to reform, to abandon the racial animus that has been central to their practices through much of American history. The movement against police racism and police brutality has already been globalized, and now social forces dedicated to democratizing democracy are rewriting the political and cultural content of citizenship. And thus, from Germany and France to Indonesia and Brazil, the marginalized are joining with progressive social forces in redefining what civic responsibility and popular agency look like in the making of democratic society.

I contend that the global subalterns and historically marginalized peoples are the ones who have pushed the international system to adopt whatever level of democratic governance exists. Numerous wars of liberation and anti-colonial/anti-racist struggles produced political independence and national sovereignty—the key foundations on which democracies are built. The subalterns have had to rectify the contradictions of global liberalism by transforming the idea of freedom for some into the practice of freedom for all.

IR Should Abandon the Notion of Aid, and Address Racism and Reparations

By Olivia U. Rutazibwa, a senior lecturer at the University of Portsmouth and a fellow at the Johannesburg Institute for Advanced Study. She is a co-editor, with Robbie Shilliam, of The Routledge Handbook of Postcolonial Politics.

When I decided to study international relations 20 years ago, I was not interested in which among realism or liberalism—or the new kid on the block, constructivism—was the proper theoretical approach.

Instead, I came to study IR because, as a second-generation Rwandan born and raised in Belgium, I could not wrap my head around what happened in 1994. Then a teenager, looking at the existential distress of my family members—rather than at my schoolbooks—I understood that something apocalyptic was unfolding in Rwanda. The United Nations, meanwhile, was retreating from the country, after 10 Belgian U.N. blue helmet paratroopers had been murdered on the eve of the genocide against the Tutsi.

In the Belgian media, apart from the death of the Belgian troops, the events were recounted vaguely like any other seemingly ethnic conflict in Africa—with Belgium’s and other Western involvement underplayed or erased. Many Belgians are still unaware of Belgium’s colonial ties to both Rwanda and Burundi, nor are they clear, if at all conscious, about who killed whom.

My interest in IR came from the fact that I could not make sense of the fact that the U.N.—which, according to my IR textbooks, was a Western-led beacon of hope and salvation and the cradle of human rights—left a million people to die in 1994.

I therefore set out to study what is known as “ethical foreign policy”: international (i.e., Western-led) actors showing up for the other peoples of the world with the well-being of the supposedly receiving others proclaimed as the driving force behind their presence. Building on mainstream IR, usually dead silent about racism and colonization, at the time, I viewed more involvement (financial, political, and technical) as an ethical given.

Yet, there is no historical evidence that Western presence has ever enhanced the well-being of the previously colonized world. It took me a solid decade—and exposure to post- and decolonial approaches—to change my doctoral research question from: “When do Western actors not show up?” to “Should they be there in the first place?”

Ever since I discovered—through the works of colleagues like Errol Henderson, Meera Sabaratnam, Siba Grovogui, and Robbie Shilliam—that one can include analyses of race, racism, colonialism, and paternalism in the study of the international and present-day North-South relations, I have come to the conclusion that we should get rid of the notion of aid and the related discipline of international development, which, like IR, is built on a profound whitewashing of history and the erasure of the contributions of previously colonized people to wealth and advancements in the West. Indeed, the entire notion of aid is obscene—and racist. International relations that do not reproduce the logic of colonialism must instead engage with ideas of repair, dignity, and even retreat.

It is also not just about adding a bit of racism and colonialism and stirring. It means fundamentally rethinking the purpose of the discipline: Do we make it a science of the status quo or a science of the possibility of life—starting with Black lives?

Earlier this week, on June 30, the king of Belgium expressed for the very first time in history his regret for the countless brutal acts committed during the colonial era in the Belgian Congo—60 years after formal independence.

IR scholars who place race, racism, and colonialism at the center of their analysis know that it is about more than acknowledging the past. The scholarly imperative is to study and question the current international system built on racial capitalism, and to imagine alternatives. At best, Belgium’s belated gesture is the start of a conversation about repair and reparations, not aid—a conversation that mainstream IR, as it exists today, has not been able to ignite.

The Field of International Relations Wasn’t Born Where You Think It Was

By Vineet Thakur, a lecturer at Leiden University and the current Smuts visiting fellow at Cambridge University, is a co-author of South Africa, Race and the Making of International Relations.

The established story runs that the IR discipline is a child of World War I. In a world weary of destruction, so the familiar founding myth goes, a new and supposedly scientific discipline was needed to mitigate the problem of war. Only a dispassionate, reasoned, and objective study could lead to new pathways out of it—leading to the founding of a department at Aberystwyth University in Wales and an institute of international relations on the sidelines of the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. This story is only half-true, however.

There is another war that was equally important to the founding of IR: the South African War, also known as the Boer War, of 1899-1902. The Union of South Africa, a racist state forged out of four warring proto-states and the constituents of the British Empire in 1910, became the model for how the institution of war could be tamed.

The men, the method, and the money involved in this mythmaking, as Peter Vale and I argue in a recent book, are crucial precursors to understanding the individuals, ideas, and the institutions involved in the founding of IR as an academic discipline.

The Round Table, perhaps the singularly most important network responsible for the creation of several early chairs, institutes, and journals in the IR field, drew almost entirely on the early work of its core members in South Africa, then known as “Milner’s Kindergarten,” named after the British colonial administrator who was high commissioner of South Africa during and after the war.

They money for IR’s early initiatives, including its first institute, London’s Chatham House, and one of its first journals, the Round Table, came from the South African mining magnate Abe Bailey, a key ally of the imperialist politician Cecil John Rhodes. The Round Table’s racial ideas, developed first in South Africa, later served as templates for the interwar ideas of the British Commonwealth and the so-called World State. Indeed, the life and work of Chatham House’s founder Lionel Curtis is the thread that links the gold mines of Johannesburg to the Union of South Africa to the British Commonwealth to the idea of a world government.

This alternative origins story raises two crucial issues in thinking about race and the making of IR—as an academic discipline and as a field of practice. First, to analyze racial constructions of the world, scholars’ archival gaze must expand beyond the United States and Britain. Important as it is to understand race and its role in the making of IR from the American or British perspectives, studying only these contexts excludes the people of the rest of the world. Second, race almost always operates in conjunction with other categories—such as caste, class, civilization, and, in today’s context, the racialized Muslim.

The challenge for IR is to find a new language that is not confined to just one master concept or one corner of the world.

Race and Empire Still Haunt IR

By Duncan Bell, a professor of political thought and international relations at the University of Cambridge.

The global Black Lives Matter protests have amplified interest in the role played by ideologies of race in both the dynamics of world politics and the discipline of international relations.

Social scientists furnished legitimacy for a world structured by imperial exploitation and pernicious racial hierarchies. Race was often viewed as the basic unit of politics—more fundamental than state, society, nation, or individual.

The “religion of whiteness,” as the civil rights activist and scholar W.E.B. Du Bois termed it, was common (though not unchallenged) across the Euro-American world. As Robbie Shilliam of Johns Hopkins University argued recently in Foreign Policy, it was manifested in the “color line,” that Du Bois saw as an organizing principle of international politics. Yet many IR scholars today, Shilliam observes correctly, “have carefully avoided reflecting on the role race plays in our field.”

In a forthcoming book, Dreamworlds of Race, I scrutinize a white supremacist version of “racial utopianism” that was popular at the dawn of the 20th century—the fantasy that the “Anglo-Saxons” (or “English-speaking peoples”), if unified politically, could bring peace and justice to the earth. Many eminent individuals proselytized the idea, including Andrew Carnegie, who ended up creating the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and the arch-imperialist Cecil Rhodes.

Though the most extravagant versions of Anglo-utopianism were exhausted by the mid-20th century, the idea that the “English-speaking peoples” are destined to play a leading role in shaping world politics has proved remarkably durable. It has resurfaced in assorted conservative visions of the so-called Anglosphere and in projects for reorienting Britain’s post-Brexit foreign policy.

The intertwined histories of race and empire haunt the present. Yet the Black Lives Matter movement demonstrates the productive power of collective action and the possibilities for rethinking history in the service of a more equitable future. If mainstream IR is to play a part in this vital endeavor it needs to address questions of imperial and racial domination, past and present, far more seriously than it has done in recent years.

Eurocentrism in IR Is a Form of Intellectual Racism

By Karen Smith, a lecturer in international relations at Leiden University and an honorary research associate at the University of Cape Town, is the co-editor, with Arlene Tickner, of International Relations From the Global South: Worlds of Difference.

In the same way that international relations has neglected race, the discipline has been both ignorant and dismissive of alternative ways of thinking about the world that do not, according to a Eurocentric understanding of history, originate from the West.

Ideas from outside the West have been deemed inferior in the field of IR and lacking in value because of their geographic origin, because they are not couched in the theoretical language regarded as legitimate by the gatekeepers of IR or do not appear in forms—such as recognized academic journal articles or books—that are considered to be appropriate sources for the study of IR.

In addition, scholars from beyond the West have, in a way that reflects the global economy, been relegated to the role of providers of raw material—in the form of empirical evidence—while the transformation of these facts into more advanced, abstract forms of knowledge has been regarded as the prerogative of the West. For example, Western scholars often assess African states according to criteria developed by European theories of statehood and rely on local scholars to provide the relevant data, instead of considering alternative African understandings of the state.

As a consequence, the majority of what students read about in IR continues to be written by a minority of the world’s people. The presumption that all worthwhile ideas originated in the West is not only exclusionary but false, as scholars such as Pinar Bilgin and Siba Grovogui have argued—and should be acknowledged as constituting a form of intellectual racism.

The exclusion of scholars and ideas from outside Europe and North America has resulted in a field that does not provide those who study it—and often go on to practice it as, for example, diplomats and politicians—with the necessary diversity of perspectives to fully grasp the dynamics of the contemporary global system. Perhaps most significantly, it has constrained the discipline’s ability to imagine a different world.

Feminist Foreign Policy Cannot Ignore Race

By Toni Haastrup, a senior lecturer in international politics at the University of Stirling and the co-author, with Jamie J. Hagen, of “Global Racial Hierarchies and the Limits of Localization via National Action Plans” in the book New Directions in Women, Peace and Security.

Across the world, countries are adopting new foreign-policy practices to redress inequalities within the global system. One of these is Sweden’s feminist foreign policy. Established in 2014, this approach to foreign policy was led by former Swedish Foreign Minister Margot Wallström, and it draws attention to the implications of discrimination based on gender and the absence of women in the field of international relations, including foreign-policy practice.

Feminist foreign policy has now gone beyond Sweden, to include countries like Canadaand, recently, Mexico.

While these moves toward a foreign-policy approach informed by feminism is important, they can reinforce enduring blind spots within the field and practice of international relations by ignoring race. Feminist foreign policy often allows wealthy countries to focus attention on the plight of women in countries with developing economies. Wealthier countries, or developed economies, then position themselves as being better placed to respond to the challenges around gender discrimination.

The assumptions encoded in the relationship between developed and developing economies are thus racialized. A country with a feminist foreign policy often invokes its own experiences as good practice elsewhere. Yet gender discrimination is universal, and often members of minority groups within the developed economies are significantly disadvantaged by endemic racism and xenophobia. Further, in emphasizing gender-based discrimination “elsewhere” as the core inequality, this dominant brand of feminist foreign policy fails to consider seriously the racialized legacies of colonialism that lead to the conditions of gender discrimination in developing economies.

For feminist foreign policy to provide a transformative alternative to the current practice of foreign policy, an explicit consideration of race is necessary. Race in IR is not new, so why treat it as irrelevant in the quest for more egalitarian and just societies? A movement of transnational feminists provides a way forward for reflection and thinking through how to challenge the structural violence—the harms caused by social structures to disadvantaged peoples—that upholds the dominant practices of international relations.

In accounting for structural violence, and thus acknowledging how an explicit consideration of race impacts foreign policy, the Feminist Foreign Policy Project—a group of activists, academics, and practitioners—has called on wealthier countries to halt the arms race; reconsider military interventions in developing economies; reverse the trend of increased militarism via increased military spending; and rethink the championing of economic policies that invariably increase inequalities. Paying attention to these systemic issues that originate in wealthier countries is a transformative plan that could begin to tackle the inequalities within international relations.

A different way of doing foreign policy that is people-led rather than state-led and emphasizes solidarity over interest is the only means toward justice for all.

The West’s Triumph Led to Racial Catastrophe. Its Decline Could Lead to Racial Justice.

By Seifudein Adem, a professor of global studies at Doshisha University.

According to the late political scientist Ali Mazrui, the first phase of global cultural encounters led to genocide in the Americas and the trans-Atlantic slave trade. This was the era of the West’s ascendance. The second phase was the period of colonialism and imperialism, through which the world has recently passed. This was the era of the West’s triumph. Both these phases resulted in racial catastrophes.

At a deeper level, what the world is witnessing today could be the third phase of cultural encounters. The pretention of Western culture to universal validity is being challenged from the angles of cultural relativism (what is valid in one society in the West was not valid in another); historical relativism (what was valid in the West at the beginning of the 20th century was not valid in the West at the beginning of the 21st); and empirical relativism (the West often failed to live up to its own standards, and occasionally those standards were better met by other societies).

Indeed, the rejection of the process that makes all of us look similar (homogenization) while making one of us the boss (hegemonization) seems to be well underway. This is the era of the West on the defensive.

In recent months, COVID-19 emerged and spread globally. In response to the coronavirus pandemic, there have been noticeable lapses of standards in many Western societies, while those standards were better met by several non-Western societies. The world has also witnessed, more recently, the global spread of protests demanding justice for George Floyd, an African American man cruelly killed by police in the United States. Many of those who protested in different countries might not have known all that much about the specific issues and may not have even spoken English. But that so many knew about the incident at all and felt strongly about it to come out to protest is itself something.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the global protests against police brutality demonstrate that, first, the challenges to humanity transcend the territoriality of the state and the parochialism of race and, second, a transnational, if rudimentary, convergence of political sensibilities may be emerging at the grassroots level. For many around the world, the moral disease of racism needs to be confronted as vehemently as the physical disease now sweeping around the globe.

These shared sensibilities could, in the long run, become a catalyst for something bigger: the creation of a truly global village that is based not on cultural hierarchy but on what Mazrui called cultural ecumenicalism—a combination of a global pool of achievements with local pools of distinctive innovation and tradition. We should hope so.

Article originally published by Foreign Policy in 03/07/2020