African Modernity from Johannesburg: William Kentridge's Other Faces

If any African artist working today can be described as internationally acclaimed, instantly recognizable, with a style marked by a unique personality, it is the South African William Kentridge. A ubiquitous presence in art festivals and exhibitions and in the permanent collections of the great museums, a recipient of numerous prizes, encomia, and honorary doctorates, Kentridge was born in Johannesburg in 1955, when popular uprisings and increasingly harsh repression drew clear lines between partisans and opponents of the racist authoritarian regime.

William Kentridge. Other Faces. Marian Goodman Gallery, NY. Photo by Beatriz Leal Riesco.His origins in a family of European stock and of liberal cultural heritage, committed to the struggle for racial equality and universal human rights—his father represented, among other clients, the family of slain Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko—was no doubt instrumental in forging the Kentridge’s critical spirit and combative posture, both as an artist and as a public figure. Kentridge, with one foot in Africa and one in the West, bypasses the three stages in the intellectual’s evolution proposed by Franz Fanon—assimilation, negation, and militancy—and the stale, simplistic pamphletarianism these imply, in favor of a dialogic approach directed from, and enriched by, contemporary South African reality. His life and work embody that specifically African modernity, rooted in the continent’s transnational culture and promulgated by artists and intellectuals, that the Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbebe proposes with the term Afropolitanism. This concept, developed in his most recent work, Sortir de la grande nuit. Essai sur l’Afrique décolonisée (2010), proposes an amalgam of the utopian and the pragmatic, guided by cultural figures who are at once depositories and exponents of a new civic culture. Afropolitanism conceives of utopia in artistic accents and endorses the artistic as a practical avenue of change; in doing so, it reveals a largely unknown modernity, urban and African, rooted in Dakar, Abidjan, and Nairobi and now in full flower in Johannesburg, taking inspiration “from multiple racial heritages, from a vibrant economy, from a culture of consumption that participates directly in the flows of globalization. It is in the process of creating an ethic of tolerance capable of reanimating the esthetic and cultural creativity of Africa in the same way as Harlem and New Orleans did formerly for the United States.”

William Kentridge. Other Faces. Marian Goodman Gallery, NY. Photo by Beatriz Leal Riesco.His origins in a family of European stock and of liberal cultural heritage, committed to the struggle for racial equality and universal human rights—his father represented, among other clients, the family of slain Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko—was no doubt instrumental in forging the Kentridge’s critical spirit and combative posture, both as an artist and as a public figure. Kentridge, with one foot in Africa and one in the West, bypasses the three stages in the intellectual’s evolution proposed by Franz Fanon—assimilation, negation, and militancy—and the stale, simplistic pamphletarianism these imply, in favor of a dialogic approach directed from, and enriched by, contemporary South African reality. His life and work embody that specifically African modernity, rooted in the continent’s transnational culture and promulgated by artists and intellectuals, that the Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbebe proposes with the term Afropolitanism. This concept, developed in his most recent work, Sortir de la grande nuit. Essai sur l’Afrique décolonisée (2010), proposes an amalgam of the utopian and the pragmatic, guided by cultural figures who are at once depositories and exponents of a new civic culture. Afropolitanism conceives of utopia in artistic accents and endorses the artistic as a practical avenue of change; in doing so, it reveals a largely unknown modernity, urban and African, rooted in Dakar, Abidjan, and Nairobi and now in full flower in Johannesburg, taking inspiration “from multiple racial heritages, from a vibrant economy, from a culture of consumption that participates directly in the flows of globalization. It is in the process of creating an ethic of tolerance capable of reanimating the esthetic and cultural creativity of Africa in the same way as Harlem and New Orleans did formerly for the United States.”

William Kentridge. Other Faces. Marian Goodman Gallery, NY. Photo by Beatriz Leal Riesco.

William Kentridge. Other Faces. Marian Goodman Gallery, NY. Photo by Beatriz Leal Riesco.

Kentridge, his complaints about the provinciality of Johannesburg notwithstanding, has remained faithful to this city throughout his life, both as resident and as promoter of its conversation with the West. The whole of his work—rich and multidisciplined, experimenting with numerous media and artistic idioms, its reflectiveness informed by an outlook both organic and intertextual—comprises an analysis of contemporary South Africa. Just as the city grows, establishing relations spiritual and social, historical and economic, among its citizens, its geography, and the events that take place there, so Kentridge’s works evolve before the spectator’s eyes. The intention is to open up, by means of auditory and visual perception, a space for thoughts and judgments of an engaged and political stamp. The reverberations between Kentridge’s personal history and that of South Africa, with their parallels to the dilemmas of contemporary man, forced to confront the ravages of the preceding century and to critically revise his understanding of the present, make a consideration of his work essential to any broader analysis of contemporaneity.

Born into a family committed to the struggle against apartheid, Kentridge earned his degree in Political Science and African Studies from the University of Witwatersrand before leaving his home country to study mime at the École International de Théâtre Jacques Lecop in Paris. Though this experience convinced him that his future lay in the plastic arts, he maintained his connection to the stage, working as an artistic director for stage and television and, most importantly, with the Handspring Puppet Company, which was founded in 1981 and has survived to the present day. His set pieces are among his greatest achievements, and his esthetically purified approach to mise-en-scène has led him to expand his range to include operas—most recently, in Mozart’s Magic Flute at the Teatro alla Scala di Milano (March 20 – April 13, 2011), but also in Shostakovich’s The Nose at the Metropolitan in New York, in coproduction with the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence and the Opéra National de Lyon.

His trajectory has not lost its performative focus. Last month in New York he debuted the newest chapter of his most famous series, Drawings for Projection, ten short films dating from 1989 through the present day: Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City After Paris (1989), Monument (1990), Obesity & Growing Old (1991), Felix in Exile (1994), History of the Main Complaint (1996), Weighing and Wanting (1998), Stereoscope (1999), Tide Table (2003), and Other Faces (2011).

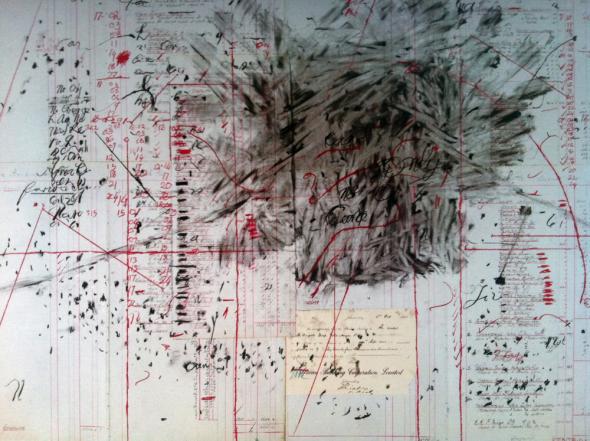

The technique is simple: the recording, in 35mm, of charcoal drawings on paper, erased and redone on the same surface until it is worn down and torn and over which, at times, another sheet, as a last resource, must be hung. The interruptions, leaps, and substitutions shown represent a kind of premeditated discontinuity. In reality, these “drawings for projection” are merely animated shorts and their titling otherwise a semantic quibble owing, in great measure, to the disdain still directed at this medium from the world of High Art. These pieces, more so than any of Kentridge’s other works, are characterized by a subtle but still firm directness, and suggest a plethora of possible interpretations, provided the spectator is acquainted, not only with the artist’s previous production, but with the interrelations of the Western and African art traditions, the latter of which, it is often forgotten, nurtured the former even before the age of colonization.

William Kentridge. Other Faces. Marian Goodman Gallery, NY. Photo by Beatriz Leal Riesco.Other Faces had its world premiere in the Marian Goodman gallery, a cleanly lit, capacious, industrial-style space in central Manhattan. The filmed portion of the exhibit is placed centrally, flanked by the paper drawings that composed it. In this way, the gallery and the artist affirm the growing importance of the evolution of the artwork in time—a posture no less remunerative than esthetic, given that single drawings from the series sell for no less than six figures. In relation to this autonomy of the various creative phases, we must emphasize the importance attached to formal leaps and transitions, apertures which the spectator endows with meaning and for which the collaboration of his longtime editor and composer, Catherine Meyburgh and Philip Miller, respectively, are essential. The montage, in concert with the dramatic score, dictates the course of Other Faces. If one must search for differences, or for an alleged evolution, between the present work and its predecessors, one may say that the latter are more classical, not only in their formal transitions but in their manner of narration and pictorial lexicon.

William Kentridge. Other Faces. Marian Goodman Gallery, NY. Photo by Beatriz Leal Riesco.Other Faces had its world premiere in the Marian Goodman gallery, a cleanly lit, capacious, industrial-style space in central Manhattan. The filmed portion of the exhibit is placed centrally, flanked by the paper drawings that composed it. In this way, the gallery and the artist affirm the growing importance of the evolution of the artwork in time—a posture no less remunerative than esthetic, given that single drawings from the series sell for no less than six figures. In relation to this autonomy of the various creative phases, we must emphasize the importance attached to formal leaps and transitions, apertures which the spectator endows with meaning and for which the collaboration of his longtime editor and composer, Catherine Meyburgh and Philip Miller, respectively, are essential. The montage, in concert with the dramatic score, dictates the course of Other Faces. If one must search for differences, or for an alleged evolution, between the present work and its predecessors, one may say that the latter are more classical, not only in their formal transitions but in their manner of narration and pictorial lexicon.

Kentridge’s exploration of the artistic consequences of the intimate portrait of the city situates him in a historical line that includes the abstract visual symphonies of Viking Eggeling and Hans Richter and Walter Ruttman’s BERLIN: die Symphonie der Großstadt. In this way, Kentridge vindicates a body of once-influential work—particularly in cinema—neglected for decades as a result of the growing tendency in artistic representation to reduce urban space to its spectacular or picturesque elements. In his prints, his set-pieces, and, markedly, in his drawings for projection, Kentridge has deepened our understanding of the dilemmas faced by these forebears. His blending of abstract and figurative portrayals present a world under perpetual construction, a time-image, vibrant and multiform, aimed at maintaining the spectator in a state of meditative alarm, so that his reflections, taking leave of the pieces’ form, arrive at a content engaged in the constant process of stripping itself bare. This critical dynamism marks a relation between Kentridge and South Africa’s expressionist comics movement: both represent an ongoing dialogue between cultural production and contemporary urban reality.

In Other Faces, the protagonists are, as before, Soho Eckstein, businessman and real estate developer, his wife, and his counterpart Felix, a poet, lover, and vitalist uncorrupted by the vices of capitalism. New faces are brought in (the Sphinx from a series of Egyptian drawings at the Louvre as well as more urban images) alongside citations of earlier works and invocations of individual and collective memory, recalling South Africa’s decades-long negotiation with its past amid unyielding xenophobia and violence. This commendation of memory in the reconciliation with versions of the past at times irreconcilable for the distinct groups that embrace them, with its stress on the possibilities of forgiveness and understanding, is essential in a country where revenge through violence is the rule of the day, as Coetzee and many others have chronicled. But Other Faces is not limited to time-bound themes. With his characters, Kentridge plumbs man’s depths, his contradictions, his reactions before the world, the weight of emotional memory, of individual and collective history, the sense of belonging and the need to weigh up those ideas we have held to lie at the roots of our liberation.

William Kentridge. Other Faces. Marian Goodman Gallery, NY.

William Kentridge. Other Faces. Marian Goodman Gallery, NY.

The reflections exemplified in his theatrical set-pieces and his frequent recourse to puppets—often more human than the people to whom they refer—continue in the theoretical avant-garde tradition of which Brecht’s Episches Theater, Artaud’s Théâtre de la Cruauté, Kantor’s Theater of Death, and, in the present day, Peter Schumann’s Bread and Puppet Theater. One must emphasize these referents as a counterweight to the reliance on assemblage, now a commonplace in the contemporary analysis of African art, with its excessively postmodernist, postcolonial obsession with hybridization, subversion, and other fad-concepts the insistent reliance on which renders a more substantive analysis impossible. That said, one must be grateful for any recognition, however token, of the possibility of African art as a self-sufficient entity, and the increasing number of exhibitions thereof, and the proliferation of texts surrounding them, show that this process is underway. It is true that Kentridge gathers together and reuses found materials, bringing them into contact with paper, pencil and pen, the principle elements of his work: cheap materials, unpretentious, accessible to whomever, and touchstones in the history of man as artist. In Kentridge’s hands, recycling is another step in the transmutation of the objet trouvé into art by the gesture of its creator, as Duchamp envisioned it a century ago. The media employed—particularly charcoal, with its clear reference to preliminary studies—make reference to art as a process of searching, of feeling out. This is likewise evident in the choice of 35mm. Despite the clear technical and economic advantages of video and digital, it is film that best alludes to the contradictions of the twentieth century. Celluloid, today in decline, is paradigm and depository of recent memory—and nowhere more so than in Africa, where it has served both as justification for and indictment of the depredations of colonialism, as a vindication of the struggle for independence, as a model for the oppressive and liberatory possibilities of the image. Cinema and photography are irrevocably bound to the construction and negotiation of identity in modern life, bearing constant witness to modern power struggles and opening up space for individual and collective action. A recognition of the responsibility of the artist and of creation in these realms, of the weight of ethical and esthetic engagement, is one of the signal aspects of Kentridge’s poetics.

William Kentridge, a modern artist working from within South Africa’s turbulent and suggestive urban reality, invites us to reflection by making visible the ignored faces—temporal, spatial, human—of his city. The thematic and formal symmetry of his most famous series, of which Other Faces is the most recent continuation, offers an analysis of South Africa’s past, present, and future challenges. Comprising at once “a stylistics, an esthetics, and a certain poetic of the world”—Mbebe’s definition of Afropolitanism—these works represent the sort of marriage of culture and praxis necessary if change on the continent is to take hold.

William Kentridge’s Other Faces. Marian Goodman Gallery, NY. May 6 – June 18, 2011