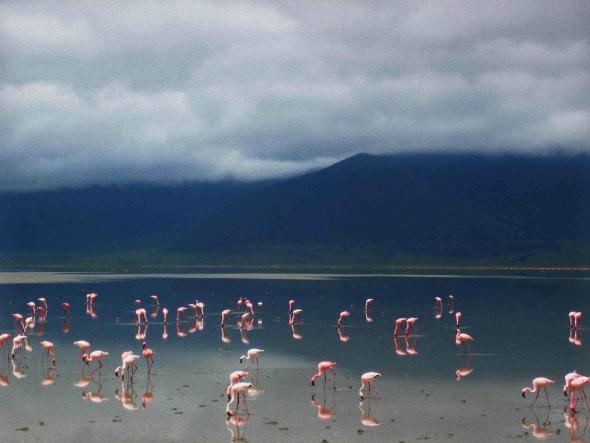

Here in Ngorongoro

Here in Ngorongoro, the flamingos spread across the lake’s low waters, walk erratic steps and peck the mud with greed. Reflections of the flamingos and of the sky, punctuated by clouds, paint the water in blue, rose and white.The wind disperses the clouds ceasing their self-admiration on the mirror; the afternoon is going to heat up.

In northern Tanzania, West of the Kilimanjaro and on the way to the famous Serengeti National Park, exists one of the bigger cauldrons in the world: the Crater of Ngorongoro. It’s the interior hollow of an extinct volcano. In its last eruption, large fissures opened, and the cone’s top crumbled over the land below. The smouldering crater left the darkness and opened to the world, cooling the fury. Day after day, over millions of years, it transformed until becoming a hospitable ecosystem of 120 square miles protected by the boiler walls, 2,000 feet high.

Here, a small portion of Africa is reserved, totally apart.

photo by Nuno Milagre

photo by Nuno Milagre

Once called Noah’s Ark and Garden of Eden, its fauna suffered great casualties produced by the subsistence of local hunters and the sport of European hunters, but it is now a protected reserve and has recovered its equilibrium.

Driven in jeeps by park guides, the tourists can observe the fauna in the interior of the enclosed plateau, including big animals like elephants, not being clear how they arrived or if they leave once in a while. Either way, there’s enough room to live a whole life, why should they leave when they can inhabit a commonwealth in the peace of the extinct crater, where even the laws of the jungle seem to be gentler?

The sight from the top of the crater is dazzling, and life goes on down there, calm and vigorous in its continuous show, even if without any audience in the amphitheatre. They call it the Eight World Wonder and it is, undoubtefully, wonderful.

Further North, Ethiopia has an Eight Wonder to present to the world: the Christian Churches of Lalibela, built in the 12th Century. Four temples were carved on the rock. Digging from top to bottom, an immense block of raw rock was isolated where the churches were opened. Others were made in cavities opened in the rocks. It’s an amazing achievement, breathtaking for the tourists and inspirational for the pilgrims, local Orthodox Christians.

Everyone wants to have the Eight Wonder of the World in their own backyard, and in the absence of a ready-made one in Libya, Muammar Gaddafi built his own. In 1984, he laid the first stone in the building of the ambitious project: The Great Man-Made River Project. It is today one of the biggest pipe networks in the world, almost 3,100 miles of subterranean channels bringing fresh water from millenary aquifers which rested under the sands of the Sahara Desert.

To Gaddafi, this is the real Eight Wonder of the World. They found this one when looking for another.Searching for oil under the desert in the 50’s, the Libyans found this immense water reserve and today, in many coastal cities in the country, glasses of desert water are drunk.

photo by Nuno Milagre

photo by Nuno Milagre

In August 2007, in South African terrain, was found what was immediately called the biggest diamond in the world, one more acclaimed Eighth World Wonder. Up to that day, the Cullinan, – found in the Johannesburg area in 1905 – was considered to be the biggest diamond in the world. It was transported to Europe under great security measures and cut into several diamonds in Amsterdam.

The bigger were inlaid into the Royal sceptre, the crown and other accessories of the British royalty, and there they shine on today. In comparison, this new finding seemed to have between 6500 to 7600 carats, the double of the Cullinan’s 3100 carats. But after a five weeks’ soap opera full of media speculation, mystery and suspense, the diamond was reclassified as “piece of plastic”. The false diamond had served to inflate the prices of the land it came from, in a business in which the South-African specialist in diamond mining and prospection, Andre Harding, would sell the property to Brett Jolly, a British business man, seducing him with this other-worldly wonder.

Here in Ngorongoro, the variations of the diamond prices or the implacable pressures of the markets on troubled countries do not disturb, for the moment, the zebras’ mood in their afternoon herd stroll: physical exercise demanded by nature for survival. Four ostriches and an elephant share the concave horizon of the cauldron while a pack of lionesses with cubs take a deserved nap. The laws of the jungle are clear and are not subject to the sudden migraines of the markets or the harassment of feline lobbies.

Dozens of yellow acacias savour their immobility from their high beauty and ignore that they were called Yellow Fever Trees when the Europeans thought the disease was spread by their, not by the mosquitoes.

photo by Nuno Milagre

photo by Nuno Milagre

Here in Ngorongoro, the terrain conditions are also measured in indexes and values, and all of those could be represented through coloured graphics if anyone bothered. The variations are indexed to Mother Nature, and therefore everything is quiet now; neither birds nor wind can be heard.

There is no means of speculation with the clouds already out of sight; but they will come back, tireless atmospheric travellers, resembling the virtual money when crossing borders visa-free and without paying taxes.

Published in Fugas’ magazine for the newspaper Público, in September 2008