Panoramic in Moving Fragments, or Mónica de Miranda’s Twin Visions of (Un)Belonging

In the recent project Panorama (2017), Mónica de Miranda returns yet again to looking at modernist architecture in Angola. In Hotel Globo (2014-2015), she had already critically examined the changing urban surface of Luanda through video, photographic and performative incursions into the interior landscapes of the 1950s Hotel Globo. The modernist hotel is still functioning in Luanda’s downtown, whose architectural heritage has been increasingly replaced with gentrified high-rise luxury buildings. In Miranda’s work, the Globo became a spatio-temporal and affective ‘lens’ through which her bodily gaze looked at the multiple geographies and histories of the city – colonial, post-independence, post-Cold War, post-civil war – in order to think the complexity of its layered present and to imagine the possibility of different futures.[1]

Mónica de Miranda, Panorama, Exhibition view, Tyburn Gallery, 2017. Copyright the artist, Courtesy Tyburn Gallery.

Mónica de Miranda, Panorama, Exhibition view, Tyburn Gallery, 2017. Copyright the artist, Courtesy Tyburn Gallery.

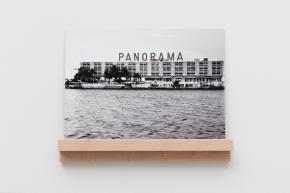

In Panorama, the abandoned Hotel Panorama – located on the island of Luanda (Ilha do Cabo) from where its guests once had panoramic views of the city and the Luanda bay, on one side, and the Atlantic Ocean, on the other – becomes the main protagonist; or so the title of the entire installation seems to tell its viewers. But, in Miranda’s non-linear – and, in fact, fairly non-narrative – visual story, there are other architectural ‘characters’ in various locations in Luanda and beyond. Furthermore, many such vacant spaces appear occupied by actual, if always enigmatic, characters; in the case of Panorama, these are twin sisters.In Hotel Globo (2014-2015), Once Upon a Time (2012), An Ocean Between Us (2012) and Erosion (2013), among other previous works, the artist herself appeared on screen alongside male collaborators, whereby she hinted at the possible narrative existence of a couple as much as at non-binary notions of identity (as far as gender, sexuality, race, nation and culture are concerned) and at a non-masculinist gaze. In these works, the characters lend themselves to being perceived as different versions of a self that could be simultaneously male and female, European and African. In Archipelago (2014) and Field Work (2016), the twin sisters made their first appearance within Miranda’s oeuvre, as another strategy to address the ‘in-betweenness’ and the ‘doubling’ of self and other and here and there that is proper to the hybrid subjectivity of diaspora. Appearing as children in the latter installations, in Panorama the twins have grown up.

Mónica de Miranda, Hotel Panorama, 2017. Copyright the artist, courtesy Tyburn GalleryAs we shall see, by drawing upon the name and history of the Hotel Panorama, the Panorama to which the installation as a whole refers poses larger questions, if always deeply personal and affective, on history, memory, desire and a condition of (un-)belonging to manifold spaces and times.[2] It also examines the notion of the ‘panoramic’ gaze and of its purportedly all-encompassing visual knowledge and pleasure. The work disrupts such a conception of the gaze and the attendant possibility of fully containing, retrieving or fixating the ever-changing processes of personal and collective becoming, particularly those marked by the diasporic experience. So, although contemplative, the gazing subjectivity in Miranda’s work is far from totalized and totalizing and, instead, avowedly fragmented and fragmentary. The gaze – bodily, psychic and geographically and historically situated – is split into many gazes. It does attain some sort of panoramic view, but only by the juxtaposition of its fragments. Such fragments do not equate the separated and categorized parts of a given totality that is divided into components only to be thoroughly mastered and seamlessly made whole again as an object of power/knowledge.[3] They do not equate mere playful signifiers either, lending themselves to the endless game of reification and commodification of histories, spaces and identities proper to what Frederic Jameson famously called the postmodern cultural logic of late capitalism.[4] The fragmented and fragmentary nature of Miranda’s panoramic visions – inhabited, affective and spatio-temporally situated landscapes of architecture and nature – resist the depoliticized moment when meanings get lost and a concern for agency is done away with. Meanings are always contingent and positional, ever-changing and relational, but, as far as being and becoming are concerned, they are also arenas for struggles of recognition and resistance.[5]

Mónica de Miranda, Hotel Panorama, 2017. Copyright the artist, courtesy Tyburn GalleryAs we shall see, by drawing upon the name and history of the Hotel Panorama, the Panorama to which the installation as a whole refers poses larger questions, if always deeply personal and affective, on history, memory, desire and a condition of (un-)belonging to manifold spaces and times.[2] It also examines the notion of the ‘panoramic’ gaze and of its purportedly all-encompassing visual knowledge and pleasure. The work disrupts such a conception of the gaze and the attendant possibility of fully containing, retrieving or fixating the ever-changing processes of personal and collective becoming, particularly those marked by the diasporic experience. So, although contemplative, the gazing subjectivity in Miranda’s work is far from totalized and totalizing and, instead, avowedly fragmented and fragmentary. The gaze – bodily, psychic and geographically and historically situated – is split into many gazes. It does attain some sort of panoramic view, but only by the juxtaposition of its fragments. Such fragments do not equate the separated and categorized parts of a given totality that is divided into components only to be thoroughly mastered and seamlessly made whole again as an object of power/knowledge.[3] They do not equate mere playful signifiers either, lending themselves to the endless game of reification and commodification of histories, spaces and identities proper to what Frederic Jameson famously called the postmodern cultural logic of late capitalism.[4] The fragmented and fragmentary nature of Miranda’s panoramic visions – inhabited, affective and spatio-temporally situated landscapes of architecture and nature – resist the depoliticized moment when meanings get lost and a concern for agency is done away with. Meanings are always contingent and positional, ever-changing and relational, but, as far as being and becoming are concerned, they are also arenas for struggles of recognition and resistance.[5]

As to history, memory, desire and the condition of (un-)belonging to manifold spaces and times, Panorama’s multiple and multiplying gazes do not redeem a sense of loss of stable points of origin or rootedness – an origin that could only mythically be seen to allow for a unified vision, knowledge and experience of the world, of the self and of communities. Rather, such a loss is positively embraced in the ethico-political activity of (un-)belonging to an always shifting network of routes across continents, islands and oceans.[6] Grounded in her own autobiographical experience of being from both Europe and Africa, Portugal and Angola (with the United Kingdom and Brazil also partaking of her affective geography), the longing that arises from the loss of a stable sense of belonging does not fall into the mythic traps of nostalgia. Instead, it is transmuted into a cosmopolitan and communal desire for being at home in the world (this cosmopolitanism having, however, always to remain deeply critical, as the ability to move across borders is a privilege that a majority of impoverished subjects worldwide cannot afford).

Angola is one of Miranda’s affective landscapes of Atlantic belonging. Born in 1976 in Portugal to an Angolan mother and a Portuguese father and maintaining familial connections with relatives who stayed in Angola upon independence in 1975, Miranda’s work is deeply marked by family memories and experiences and, more broadly, by the collective histories of Portugal and Angola. In Panorama, her focus on the psychic and physical remnants of several pasts – colonial, post-independence, post-Cold War, post-civil war – within natural, urban and architectural landscapes of Luanda and beyond serves the larger purpose of examining the contradictions of the present and imagining alternative futures.

With the demise of the Cold War in the 1990s, and the definitive end of the thirty seven year-long civil war in 2002 (won by the MPLA, in power since independence), Angola entered a period of economic liberalization and accelerated growth, serving mostly its elites. One of the most visible and tangible manifestations of such economic, political and social changes has been a profound transformation of Luanda’s urban landscape, propelled by fierce real estate speculation and gentrification. These operations have had as one of their most problematic consequences the forced removal of the poor populations of centrally located slums or musseques to faraway peripheries that are not serviced by public transportation networks. Many such slums grew exponentially during the civil war, as people had to flee war-torn areas and look for easier access to resources, whose transportation throughout the country was prevented by the war. The other consequence of the profit-seeking real estate speculation and gentrification in Luanda has been a disregard for architectural heritage, all too quickly and conveniently classified for demolition so that space becomes available for high-rise office buildings, shopping malls and parking lots – a process which has become characteristic of a globalized capitalism to which Angola now fully belongs.[7]

Mónica de Miranda, When words escape, flowers speak, from the Twins series, 2017. Copyright the artist, Courtesy Tyburn Gallery

Mónica de Miranda, When words escape, flowers speak, from the Twins series, 2017. Copyright the artist, Courtesy Tyburn Gallery

Panorama addresses such complexities by focussing on the surviving, albeit abandoned, modernist buildings of the Hotel Panorama (Hotel Panorama, 2017) and of the Karl Marx Cinema in Luanda (Cinema Karl Marx, 2017), as well as on the constructed natural landscapes of the botanical gardens of the Floresta da Ilha (When Words Escape, Flowers Speak, 2017), still functioning in the vicinity of the Hotel Panorama on the island of Luanda. But Panorama’s non-descriptive and contemplative narrative also unfolds outside the capital, more specifically, in the province of Malanje and in its capital city, similarly called Malanje. Located about three-hundred kilometres east of Luanda, this region (like many others) was deeply marked by the liberation war against the Portuguese colonial rule (1961-1975) and by the civil war (1975-2002). As to the former, the violently repressed revolt of the cotton-field workers in the Baixa do Cassange in the Malanje province on 4 January 1961 is usually considered the first of a series of events triggering the beginning of the liberation war in Angola in 1961 (commonly called ‘colonial war’ in Portugal, with 1963 marking the beginning of the war in Guinea-Bissau and 1964 in Mozambique).[8] As to the civil war, it began immediately upon independence in 1975, as a Cold War proxy conflict waged by the three liberation movements: the Soviet Union and Cuba-supported MPLA, the Zaire-backed FNLA, and UNITA, supported by apartheid South Africa and the US.[9] Malanje was severely destroyed throughout the many decades and several phases of the conflict, and progressively rebuilt thereafter. But this area also has an impressive pre-colonial history, and a colonial history of resistance and struggle against the Portuguese presence from the 16th to the 18th centuries, and against Portuguese settlement since the 19th century.[10] At a more personal level, the city of Malanje was also the place where Miranda’s mother grew up. Like Luanda, it is a space where intergenerational family memories and collective histories emerge in the very material fabric of modernist architecture from the colonial period – which has been re-appropriated in various ways after independence and after the civil war, even when ruined –and of natural landscapes. The latter are shown to be as thickly woven by history and memory as architecture, not only when the vegetation appears to infiltrate and occupy the buildings, but also when nature is portrayed on its own.

Mónica de Miranda, Fall, 2017. Copyright the artist, Courtesy Tyburn GalleryFall (2017) is a photographic installation whose fragments make up an unstable panoramic view of the area surrounding the Calandula Waterfalls in the Malanje province, called Duque de Bragança in the colonial period.[11] It is accompanied by an archival black-and-white photograph of the falls meant for their touristic promotion around the 1960s, which Miranda found in a Lisbon flee market. This image provides a centrally framed and frontal view and seems to evoke a paradisiac nature, a kind of lost paradise, untouched by man. Unlike it, Miranda’s panoramic colour version highlights how this purported paradise is far from natural in any straightforward sense and, rather, deeply embedded in history. The artist underscores the sense of constructed-ness of the landscape by presenting a panorama that is comprised of uneven fragments, a diagonally layered juxtaposition of multiple frames that, in turn, evince a plural and bodily gaze, moving in the landscape. Furthermore, she directs her gaze less to the falls – peripherally represented in her composite images – than to the adjacent spaces from which they can be observed, calling attention to the situated-ness of the gazing subjectivity and avoiding the history-effacing fetishization of natural landscape found in the touristic image. The camera focusses on the remnants of a modernist hotel also from the colonial period, which is abandoned and yet re-occupied, re-appropriated by the local vegetation. The way Miranda’s photographs frame some of the landscapes within architectural structures recalls how the hotel’s verandas and ground-floor arcade once constituted the privileged ‘lenses’ through which its guests looked at the falls and, more broadly, how any visual panorama is inescapably positioned. As Donna Haraway insightfully wrote, ‘one cannot relocate in any possible vantage point without being accountable for that movement’ and ‘vision is always a question of the power to see – and perhaps of the violence implicit in our visualizing practices’.[12] Haraway rightly argued for ‘the view from a body, always a complex, contradictory, structured and structuring body, versus the view from above, from nowhere, from simplification’.[13] Miranda’s images continuously remind us of this situated-ness.

Mónica de Miranda, Fall, 2017. Copyright the artist, Courtesy Tyburn GalleryFall (2017) is a photographic installation whose fragments make up an unstable panoramic view of the area surrounding the Calandula Waterfalls in the Malanje province, called Duque de Bragança in the colonial period.[11] It is accompanied by an archival black-and-white photograph of the falls meant for their touristic promotion around the 1960s, which Miranda found in a Lisbon flee market. This image provides a centrally framed and frontal view and seems to evoke a paradisiac nature, a kind of lost paradise, untouched by man. Unlike it, Miranda’s panoramic colour version highlights how this purported paradise is far from natural in any straightforward sense and, rather, deeply embedded in history. The artist underscores the sense of constructed-ness of the landscape by presenting a panorama that is comprised of uneven fragments, a diagonally layered juxtaposition of multiple frames that, in turn, evince a plural and bodily gaze, moving in the landscape. Furthermore, she directs her gaze less to the falls – peripherally represented in her composite images – than to the adjacent spaces from which they can be observed, calling attention to the situated-ness of the gazing subjectivity and avoiding the history-effacing fetishization of natural landscape found in the touristic image. The camera focusses on the remnants of a modernist hotel also from the colonial period, which is abandoned and yet re-occupied, re-appropriated by the local vegetation. The way Miranda’s photographs frame some of the landscapes within architectural structures recalls how the hotel’s verandas and ground-floor arcade once constituted the privileged ‘lenses’ through which its guests looked at the falls and, more broadly, how any visual panorama is inescapably positioned. As Donna Haraway insightfully wrote, ‘one cannot relocate in any possible vantage point without being accountable for that movement’ and ‘vision is always a question of the power to see – and perhaps of the violence implicit in our visualizing practices’.[12] Haraway rightly argued for ‘the view from a body, always a complex, contradictory, structured and structuring body, versus the view from above, from nowhere, from simplification’.[13] Miranda’s images continuously remind us of this situated-ness.

Mónica de Miranda, Untitled, from the series Fall, 2017. Copyright the artist, Courtesy Tyburn Gallery

Mónica de Miranda, Untitled, from the series Fall, 2017. Copyright the artist, Courtesy Tyburn Gallery

Mónica de Miranda, Like a candle in the wind, 2017. Copyright the artist, Courtesy Tyburn Gallery

Mónica de Miranda, Like a candle in the wind, 2017. Copyright the artist, Courtesy Tyburn Gallery

The Fall to which the title of these works refers evokes other falls besides that of the Lucala river: the historical falls of the pre-colonial African kingdoms, of the Portuguese colonial empire, of peace upon independence, of the Marxist utopia; the ruins of modernist architecture and of its attendant dreams; the ruined nature, due to war and the capitalist exploitation of natural resources. As nature is de-exoticized and de-mythologized as paradise, Fall is obviously reminiscent of the biblical idea of losing innocence and of being expelled from paradise. Miranda does succeed at ‘expelling’ the viewer from any such notion. This polysemic Fall is also evocative of the groundlessness of the diasporic subjectivity, eventually able to transmute homelessness into unhomeliness, root into route, to be at home in the world. Finally, all these meanings pertaining to Fall are made visually manifest also in the diagonal display of the panorama.[14]

Mónica de Miranda, Swimming Pool, from the series Swimming Pool, 2017. Copyright the artist, Courtesy Tyburn Gallery

Mónica de Miranda, Swimming Pool, from the series Swimming Pool, 2017. Copyright the artist, Courtesy Tyburn Gallery

Miranda also photographed in the city of Malanje, although exact locations are never given. In Swimming Pool, the artist presents several views of an abandoned open-air modernist swimming pool, built in the colonial period and currently surrounded by musseques. Like the hotel in the Calundula Waterfalls, the swimming pool in Malanje was a leisurely site destined mostly for the white population, shown to have been re-appropriated after independence and the civil war. Today, it is not as abandoned as it might seem at first sight, since it is actually used as an improvised site for the storage and making of building materials, as the soil-filled swimming pool and adjacent spaces make evident. Like the Calundula hotel, it appears as a kind of ‘lens’ through which to contemplate the surrounding landscape, which is never too visible. One can only imagine the view from the three diving boards above, or from the lateral amphitheatre, spots that would allow one to observe not simply the now absent water, but also the landscape beyond the swimming pool’s low walls. Similarly to her Calundula images, a multifarious sense of fall emerges here, albeit not explicitly in the title. The swimming pool is a space where the fall into (rather than of) water occurs, and where nature is immediately perceived and experienced as constructed, and so more readily demystified.

Mónica de Miranda, Angolan House, 2017. Copyright the artist, Courtesy Tyburn Gallery

Mónica de Miranda, Angolan House, 2017. Copyright the artist, Courtesy Tyburn Gallery

In the city of Malanje, Miranda also photographed Angolan House (2017). This is a set of images where inhabited modernist twin houses from the colonial period are portrayed in the present as having been re-adapted, while retaining the original design.[15] They have become almost identical, but not quite. Local vegetation again partakes of the re-occupation of space, this time domestic. In Miranda’s work, actual homes and houses serve the purpose of raising broader and at the same time deeply personal questions concerning the unhomeliness of diaspora, the hybridity of its ‘in-between’, doubled and doubling subjectivity, and the political, social, economic and cultural impact of migration on urban space. The physical and psychic loss of the Angolan family home is transmuted into an Angolan House that encompasses multiple, quasi-identical twin houses, both kept and transformed over time. Intervened with wax and pigment typical of the encaustic process, these images give rise to what I have called in the title of this essay a twin (or split or double) vision of (un-)belonging. That is, an old technique used to pre-empt the loss of images by protecting them from the damaging effects of the passage of time conveys a deep sense of transformation evident in the accumulation of layers of scratched wax and pigment. Usually used to preserve paintings, the encaustic underscores the constructed nature of the photographic record and of memory, both able to retain only partially and subjectively what they make present again or re-present. The result is a vision of both the past and the present, of here and there, of self and other that avoids the pitfalls of the nostalgic loss of the home to become critically future-oriented in the world. Similarly photographed in the Malanje area and intervened with wax and pigment, Like a Candle in the Wind (2017) asks of natural landscape the questions that Angolan House raises by means of domestic architecture. Here too a fall of sorts seems to be at work, as wax could indeed have dripped from a burned-out candle on this encaustic-processed photographic surface, whose title is retrieved from the lyrics of a well-known song about ‘never knowing [where] to cling to’.[16]

Back in Luanda, one can see how similar strategies of photographic representation of modernist architecture and natural landscape serve the purpose of examining the city’s past, present and future, through the affective and ethico-political perspective opened up by personal and collective history, memory and desire. The diasporic condition of (un-)belonging to manifold spaces and times emerges by means of a bodily, moving (even while appearing to be still) and gazing subjectivity that is also geographically and historically situated.

Mónica de Miranda, Hotel Panorama, 2017. Copyright the artist, courtesy Tyburn Gallery

Mónica de Miranda, Hotel Panorama, 2017. Copyright the artist, courtesy Tyburn Gallery

In Hotel Panorama (2017), we find another instance of juxtaposed images – this time of the abandoned modernist hotel on the island of Luanda – making up a panoramic view of the façade that faces the Atlantic. This is accompanied by an archival black-and-white panoramic photograph of the hotel’s other façade, facing the city and the bay, taken between the 1960s and 1970s. The panorama shown in this image is not only architectural, but also literally inscribed in neon on top of the building as the hotel’s name. Designed by the Portuguese architect Carlos Moutinho very likely between the 1950s and 1960s, the iconic Hotel Panorama became progressively decayed during the civil war and was eventually abandoned. A renovation and augmentation plan was designed in 2007, but never carried out. Miranda’s colour and composite Hotel Panorama redirects the viewer to the landscape of city and bay that the archival image occludes, but the visual access to it only occurs as filtered by the architectural ‘lens’ of the Atlantic-facing façade. It is through the entrance, opening onto a wide window on the other side, and the ground-floor arcade that one can contemplate the urban and maritime landscape in the background. On the other hand, Miranda’s panoramic view of the hotel draws attention to the empty verandas of the modernist façade, whose Atlantic view remains outside the frame. Filtering and fragmentally displayed, one also observes how the architectural panorama of the empty hotel is inhabited by the vegetation in the foreground.[17]

Shot in the botanical gardens of the Floresta da Ilha (Island Forest) near the Hotel Panorama on the island of Luanda, When Words Escape, Flowers Speak (2017) portrays the constructed, although apparently neglected, natural landscape of the functioning gardens.[18] These images show the gardens occupied by twin Angolan sisters, centrally framed holding their hands with their eyes closed amidst a mix of vegetation. The information that this setting is a botanical garden is not given, but one senses the constructed-ness of the landscape as soon as one notices that the twins are standing between two swirling paths. Miranda analyses botanical gardens in this and other works – such as Archipelago (2014) and Field Work (2016) – in order to recall their weighted colonial histories of collecting, cataloguing and displaying specimens for European knowledge and pleasure. She examines the ways in which the spatial remnants of such colonial impulses have been re-appropriated in post-colonial times. In more personal terms, like an affective collection of portraits gathered and transportable in a family album, botanical journeys and archives also allow Miranda to think about the formation of diasporic identities between past and present, here and there, self and other, which the almost identical – but not quite – twin sisters and paths underscore. The twin Angolan sisters re-appropriate this territory with a meditative – rather than nostalgic – shared presence. Portrayed in an inward-looking moment, they seem to be listening to the manifold pasts remembered and futures foretold by the landscape itself.

From the island of Luanda, the twins move to the Alvalade neighbourhood, where they are seen wandering in the closed-down modernist Cinema Karl Marx, called Avis before independence. It was designed in the early 1960s by João Garcia de Castilho, the Portuguese architect of many other modernist buildings in the city (such as the open-air Cine-Miramar, designed with his brother Luís Garcia de Castilho in 1964).[19] In Cinema Karl Marx (2017), Miranda’s camera focusses on those spaces of the abandoned movie theatre from where the activity of watching used to (and, in her images, does) take place: the long veranda marking the building’s façade and, inside, the amphitheatre made up of the now derelict chairs.

Mónica de Miranda, Cinema Karl Marx, from the series Cinema Karl Marx, 2017. Copyright the artist, courtesy Tyburn Gallery

Mónica de Miranda, Cinema Karl Marx, from the series Cinema Karl Marx, 2017. Copyright the artist, courtesy Tyburn Gallery Mónica de Miranda, Twins from the series Cinema Karl Marx, 2017.Copyright the artist, courtesy Tyburn Gallery

Mónica de Miranda, Twins from the series Cinema Karl Marx, 2017.Copyright the artist, courtesy Tyburn Gallery

These viewing spots are inhabited by the multiple, bodily, gazing presence of the twin sisters, moving in the architectural landscape of the Karl Marx even while they appear to be still. Indeed, movement is here both physical and psychic. When the twins sit down in the empty amphitheatre, whereas one of them peers out at something outside the frame, the other looks back at the viewer, who, occupying the place of the cinema screen, thus becomes a screen of sorts, not only gazing but also being gazed at. Like the panoramas discussed previously, Miranda’s panoramic view of the cinema’s exterior façade is comprised of several juxtaposed frames, which evince a moving gazing subject not simply inside but also outside the image (even if the camera viewpoint seems centrally placed and fixed). The multiple shots, alongside the history told by the name change of the Karl Marx, its current ruined condition and its artistic reactivation, make evident the very passage of time in the fabric of space, the mythic nature of totalizing visions – be it of the gaze, the subject, history, society, origin or identity – and the imagination of alternative, shared and sharable futures. Panoramic futures, avowedly made up of moving fragments.

Notes

[1] See Ana Balona de Oliveira, ‘Os Hóspedes do Globo: (Des-)Mapeando a Memória da Cidade Vertical com a Horizontalidade do Corpo’, in Buala, 8 November 2016, http://www.buala.org/pt/vou-la-visitar/os-hospedes-do-globo-des-mapeando... Ana Balona de Oliveira, ‘Globo Lodgers: (Un-)Mapping the Memory of the Vertical City with the Horizontality of the Body’, in Mónica de Miranda, Geography of Affections 2012-2016 (Lisboa: Mónica de Miranda, 2017), pp. 111 - 123.

[2] The idea of the panorama had previously emerged in the work Panorama (2009), shot in Lisbon’s outskirts.

[3] See Michel Foucault, Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977, trans. Colin Gordon (New York: Pantheon Books, 1980).

[4] See Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, Or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (London: Verso, 1991).

[5] See Stuart Hall, ‘Cultural Identity and Diaspora’, in Jonathan Rutherford, ed., Identity: Community, Culture, Difference (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1990), pp. 222-37.

[6] See Édouard Glissant, The Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997); Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (London: Verso, 1993); James Clifford, Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century (Cambridge, Mass., London: Harvard University Press, 1997); Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London and New York: Routledge, 1994).

[7] See Ricardo Soares de Oliveira, Magnificent and Beggar Land: Angola since the Civil War (London: C. Hurst & Co., 2015); Jon Schubert, ‘2002, Year Zero: History as Anti-Politics in the “New Angola”’, Journal of Southern African Studies, Vol. 41, Nr. 4 (2015), pp. 835-53.

[8] Other events include the attack on the São Paulo Prison in Luanda on 4 February 1961, and the attacks on the coffee plantations in northern Angola led by UPA (União dos Povos de Angola, later known as FNLA, Frente Nacional para a Libertação de Angola) on 15 March 1961.

[9] MPLA refers to Movimento Popular para a Libertação de Angola; FNLA, to Frente Nacional para a Libertação de Angola; and UNITA, to União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola. Agostinho Neto was the leader of the MPLA between 1962 and 1979, and independent Angola’s first president. The MPLA was the Marxist-Leninist liberation movement which fought against Portuguese colonial rule beside the FNLA led by Holden Roberto and the UNITA led by Jonas Savimbi. It has been in power since independence. The Angolan civil war was a Cold War proxy conflict, having continued throughout the 1990s until Jonas Savimbi’s death in 2002.

[10] This was the area of the Ndongo and Matamba kingdoms from the 16th to the 18th centuries. Ndongo was ruled by Ngola Kiluanji in the 16th century and his daughter Njinga Mbandi, Queen of Ndongo and Matamba in the 17th century, is still seen in present-day Angola as a symbol of resistance against Portuguese occupation. Her statue used to be located at the Kinaxixi Square in Luanda but is now placed at the entrance of the São Miguel Fortress, where the National Museum of Military History is housed.

[11] Waterfalls had previously been examined in Lost Paradise, a part of the Archipelago (2014) installation.

[12] Donna Haraway, ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’, Feminist Studies, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Autumn 1988), pp. 585.

[13] Ibid., p. 589.

[14] The notion of the fall had previously emerged in the work Falling (2013).

[15] In Field Work (2016), one could also see a Twin House. In Archipelago (2014), besides the young twins, there were also twin islands of sorts in the panoramic Island.

[16] Bernie Taupin, Elton John, Candle in the Wind, 1973.

[17] For an indoor image of the Hotel Panorama, see Ana Magalhães, Inês Gonçalves, Moderno Tropical: Arquitectura em Angola e Moçambique, 1948-1975 (Lisboa: Tinta da China, 2009), p. 61. For a brief synopsis on the design, see ibid., p. 211.

[18] The new Luanda Botanical Gardens are going to be constructed on the hills sprawling across the Miramar, Boavista and Sambizanga neighbourhoods, with a privileged view of the bay. Boavista used to be the area of the Roque Santeiro market, one of the biggest open-air markets on the African continent, now dismantled. Sambizanga, a poor yet proud neighbourhood whose history is inseparable from that of the struggle against Portuguese colonialism, is going through demolitions. These two slum areas are located in the vicinity of the elite Miramar neighbourhood, and the changes they have been going through will entail a radical transformation of seaside northern Luanda.

[19] See Walter Fernandes, Miguel Hurst, Angola Cinemas: A Fiction of Freedom (Göttingen and Luanda: Steidl Verlag and Goethe Institut, 2015), p. 221.