The sun does not rise in the north

Do you think freedom exists?

What are the (Black) geographies of freedom that are still to be imagined?

What are the infrastructures of hope?

The advancement and proliferation of technologies of surveillance and the control of movements is a growing violation of individual and collective freedom — for many, borders are a geopolitical construct of physical and mental entrapments.

In the exhibition the sun does not rise in the north, de Miranda proposes one-person tales navigating between fictional and non-fictional narratives in the affective space of the border. The exhibition investigates the landscapes that witness hope, from the journeys of migration between Africa and Europe, set within a duality of existence and citizenship: one contemplating Europe and the other a return to Africa.

We are immersed within the contested border of Ceuta in Spain and Melilla in Morocco in these spaces of transition where the artist spent time with the territory and gathered testimonies. De Miranda gives a nuanced gaze into the familiar scenario of the ‘migration crisis’ and its relationships with the fortress of Europe, in underpinning the ongoing colonial politics of violent rejection of people that attempt to reach its soil every day.

'o sol não nasce a norte', de Mónica de Miranda

'o sol não nasce a norte', de Mónica de Miranda

the sun does not rise in the north examines the complex diversity of personal and collective histories interconnected between the migrant and the diasporic experience in Europe. It is a continuous relational praxis that de Miranda depicts and deconstructs through counter-narratives of belonging, as well as on the (re)elaboration of memory in post-colonial discourses.

The African liberation struggles, and revolutionary movements fuel the artist’s imaginaries. The building of an archive of transnational political efforts — one that reminds us to look onto the past for our current reflections, as a continuous entity in our horizons, and where liberation sits within the ongoing narratives of strength, resilience, and vulnerability. In the film o sol não nasce a norte (the sun does not rise in the north) and photographic works, the visual narratives give (back) dignity and grace to the characters through the poetics of (body) languages.

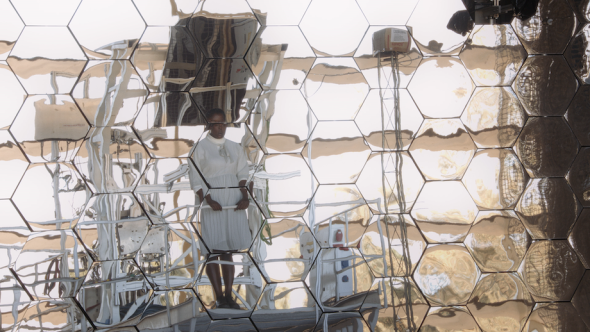

Here, and generally within de Miranda’s cinematographic geographies of affection, the main characters are in deep connections with the ecosystems and the landscapes: the sea, the forest, the mountains, the desert, the sand, and palm trees are mothering the fugitive and disposable bodies, waves are caressing the ears amongst ethereal soundscapes, symbolic spiritual colours of the sun, blood, water and trees. Clad in white clothing, they are calling for the sun. The bodies are aligned with its cyclical movement. The landscapes alternate between crisp blue skies, natural fog and blurry haze depicting the start and end of the day — and of journeys leading to freedom, alienation, loss or slow spiritual death.

In the film, the man says that the body has no end, but life does. In Bakongo philosophy, at sunset and sunrise, “the living and the dead exchange day and night. The setting of the sun signifies man’s death and its rising, his rebirth, or the continuity of his life. Bakongo believe and hold it true that man’s life has no end, that it constitutes a cycle, and death is merely a transition in the process of change.” The movements and itinerant passages of those that have arrived, but only to leave, are captured in the memory of the soil, of the land that is archiving each of their steps. In the film, the archaeological digging of the land, what was once there and now buried, interrogates what else is left of our bodies without the earth?

Now you’re this, what is left. Your body turns into pieces that the wind carries away.

'o sol não nasce a norte', de Mónica de Miranda

'o sol não nasce a norte', de Mónica de Miranda

Whether it is in the film or exhibition space, the solar panels become sculptures of dominance and empowerment bouncing the light on the bodies to rise anew within new temporality and potential forms of being and living, until a final rupture. The visitors become active participants, navigating amongst the screens, also facing the immensity of the sculptures. They roam around amongst shadows and reflections — their own stories mirroring or in tandem with the main characters. The sun is represented in the metaphor of the mirror as what controls and sustains us all. The reflective light and sun are giving the rhythm of navigation, of landmarks and human footprints. The source of light is saturated and blinding, the eyes remain shut or resist a direct gaze — a regenerative moment surfaces where the knowledge of our double co-existence is virulent and unforgivable at the core of the character’s questions and provocations in which our acts of extraction to the land is laid bare for the viewers.

But how much sun must we store and sell? How many greenhouses must we produce in order to live in a land that sees no sunlight?

The sun does not rise in the north exhibition gives way to the monumentality of the landscape of hope and freedom, the infrastructure that are markers of state violence, and the architecture of surveillance such as the metallic gated border, fences that are to rip the skin, the overwhelming visions of capitalist accumulation through extractive mechanisms as a violation of the soil, sun, water are in parallel with the ever so present technologies of renewable energies to counterbalance the damages of the land that the same politics of rejection are encompassing every day. The mirrors are an ongoing metaphor of this reflection and our contemporary interrogation on the psychological and physical damages of a systemic nature.

The sun does not rise in the north is a moment for us all to belong within their existence and continuation to resist against the distant feeling of their alienation, confusion and estrangement, and a part of the journey that liberates us from the borders of our mental and spiritual prisons in understanding the ongoing relationship that the land and our bodies are just one.

'O sol não nasce a norte', de Mónica de Miranda

'O sol não nasce a norte', de Mónica de Miranda