Black in the USSR: the children of the Soviet Africa search for their own identity

“When people ask me about my background I usually start by explaining how my mum is Russian, my dad is Ghanaian and that I was born in Bulgaria,” says the photographer Liz Johnson Artur. “It often becomes a long explanation.”

The explanation goes something like this. Along with many African students in the 1960s, Johnson’s Ghanaian father was given the chance to study in Eastern Europe as part of the Soviet Union’s efforts to expand its influence across the African continent during the Cold War. His time in Bulgaria studying biochemistry was cut short after four years when all Ghanaian students were expelled from the country following a confrontation between African students and the police. By then he’d already met Johnson Artur’s mother, who gave birth to their daughter in 1964, a few months after his departure.

Johnson Artur spent her childhood in Bulgaria and then Germany and has been based in Britain since 1990. Her father was unable to return to Bulgaria and is now settled in Ghana. She only met him for the first time in 2010. After doing so, she felt moved to start documenting the stories of other Russians of African and Caribbean origin. “Most black Russians that I met in Moscow and St Petersburg had also grown up without their fathers. Some had been fostered or grown up in children’s homes and had never met their mothers. But we all agreed that we felt Russian as well as African.”

Most of her subjects, who often describe themselves as Afro-Russians, had grown up without much contact with other black people or with little of the shared culture and identity familiar to African-Americans and black Britons. “The amount we know about our African heritage varies from individual to individual,” says Johnson Artur. What they do have in common however, is a history of struggle against a commonly encountered resistance to the presence of black people in Russia. “Those who grew up and live in Russia still have to justify on a daily basis the fact that they are Russians too.” Johnson Artur hopes her project will go some to connecting and making visible the generation of black Russians that have grown up calling the country home.

Marie-Therese

I was born in St Petersburg. Both my parents worked for the UN. My mum is Russian and my dad’s family is from Guadeloupe and Brittany. My mum’s family left Russia after the revolution. Because of my parents’ work I lived for ten years in Africa – Congo-Brazzaville, Gabon, Ethiopia. I moved back to France for my baccalaureate and after I finished my law degree I took part in an exchange program. I had a choice: Bangladesh or Russia. I chose Russia, and came to St Petersburg in 1995.

In the beginning I worked as a legal advisor on human rights issues. I also have a degree in economics, so when the exchange program came to an end I started lecturing economics at the university.

I live with my eleven cats in a small one-bedroom flat. It’s not much, but I like my life here. And I see more job opportunities here than back in France.

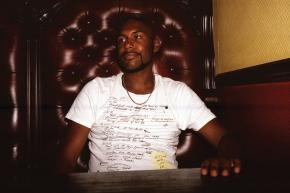

Gera

I was born in Moscow in 1961. My dad was a Cuban revolutionary who came to Moscow to study philosophy. He fought with Fidel Castro and Che Guevara in Cuba; when I turned one, he went to fight with Che in Bolivia. I only saw him once.

My mum, my brother and I lived in a very small communal flat in Moscow. When I was five, my mum got very ill. She was taken to hospital, and me and my brother – who is two years younger – were sent to a children’s home. We spent three years there. When I started school my mum took us back.

My childhood was not easy, but I have always been proud of being black. Growing up I got a lot of attention, and a lot of it was not good. Russia is quite a chauvinistic country.

They don’t like black people here.

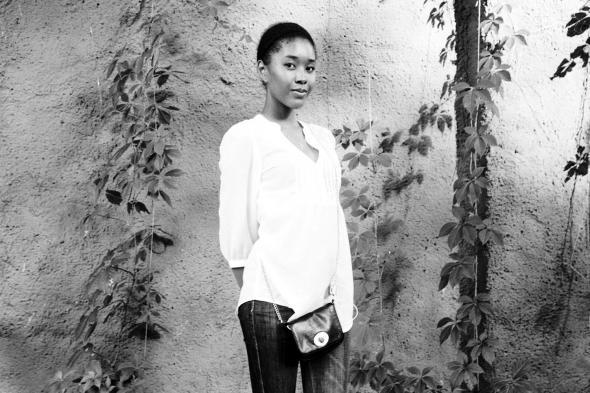

Amina

I was born in Moscow. My mum is from Russia, but she is Asian – from the Tuva Republic. My dad is from Nigeria. They met at university in Moscow. Just before I turned five my dad left; for some reason he never returned.

When I finish my studies I would like to leave Moscow. Where I study it’s very mixed and there are a lot of foreigners. I feel free and relaxed there. In the centre of Moscow I feel fine too. But I don’t really go to the outskirts of the city: it’s a very different atmosphere. I am used to being looked at, but outside the city centre I don’t really feel safe.

Vlada

I have lived in Moscow for seven years. Most of the time I feel fine here, but I would like to live in a different place. I have travelled to Brazil and Spain – people are different there, more friendly and open. Moscow is a beautiful city, but people here can be quite hard, and very nosy. Strangers trying to touch my hair is something I really don’t like.

Elena and Peter

My name is Elena. I am 55 years old. I am Peter’s mum. We live on the outskirts of Moscow. I worked as a cook in the Nigerian embassy; Peter’s dad was working as a diplomat. I always knew he had another family in Nigeria. When he left, my problems started. I used to find pornographic postcards in my letterbox. When I went out with Peter, people tried to look into the buggy to see what colour he was. Some of my friends and neighbours turned away from me.

When I sent him to nursery, parents started complaining to the nursery about taking on a black child. The staff at the nursery were supportive, but it didn’t stop the children: they would say things like, “if you touch him your hands will get dirty…” It’s easier now that he is older and can stand up better for himself.

Two years ago I won two plane tickets to Nigeria. We stayed with Peter’s dad, his wife and children. It was wonderful. We were welcomed into their house. I have very warm memories of our visit and it was wonderful for Peter to meet his brothers and sisters.

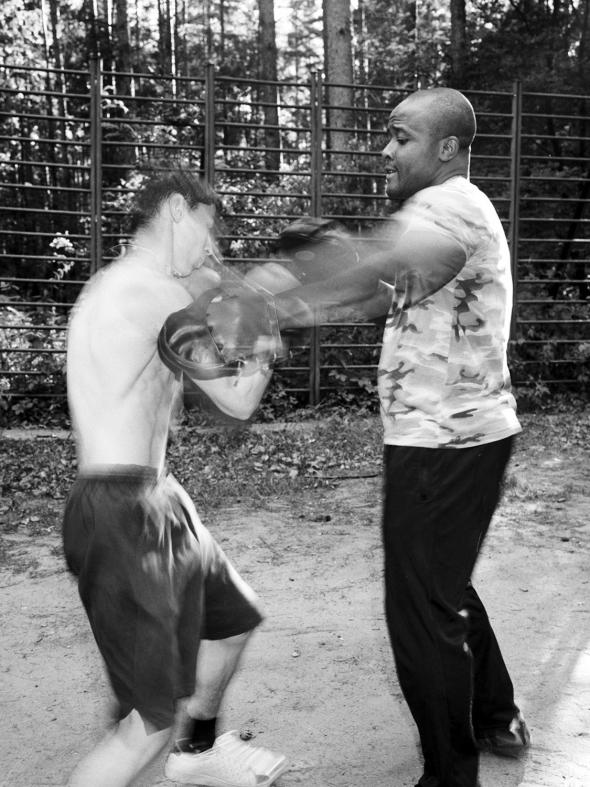

George

I came to Russia 22 years ago from the Cameroon to study medicine, but my love for martial arts took over. When I came to St Petersburg I had a son with a Russian woman. I needed to find work so I started giving martial arts lessons. Russia was good to me: it gave me the opportunity to open my own martial arts studio. I could have never done this in Cameroon.

Around 2004 there were a lot of attacks by skinheads in St Petersburg. After the death of an African student we organised a big demonstration in the city. I spoke at the rally and afterwards the FSB [Russian state security service] held me for two days, questioning me about my activities. But I don’t have any hard feelings: it takes time for attitudes to change. I also tried to join the FSB. I passed all the tests but they wouldn’t take me. But I am stubborn. I applied again for a different unit, and now I work for them on a voluntary basis.

I try to show my appreciation for what Russia has given me. For me that’s the best way to change Russians’ attitudes towards me and other black people.

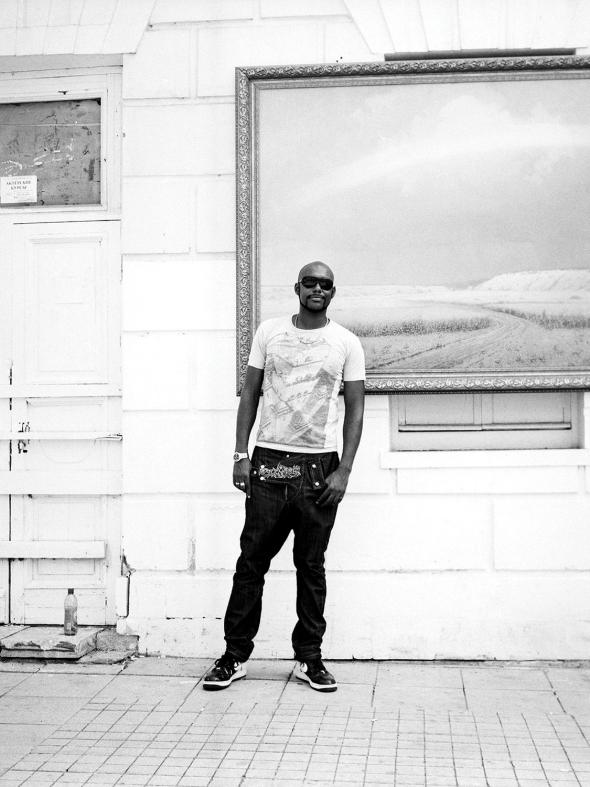

Ivan

My mum is Russian and my Dad is from Mali. I lived with my mum but we didn’t get on. She didn’t understand me. I used to run away a lot, but they always caught me and brought me back to her. When she couldn’t take it any more I moved in with my grandmother, but it wasn’t any better.

A lot of what I learned I learned on the streets: kids use to try to pick fights with me, and I fought back. When I was in the army I made sure people knew not to mess with me. I left the army with a drug habit and when I got back to Moscow I lived on the street. It was tough but it also made me very determined. I kicked my habit, and also discovered beat boxing: I even had a show on MTV Russia.

I had many thoughts about leaving. But I also worked hard to be where I am now. I don’t want to just give it all up.

Images: Liz Johnson Artur

This special report coincides with the Red Africa season running at Calvert 22 Foundation, from February 4th to April 3rd, Wed-Sun 12pm-6pm, 22 Calvert Avenue, London E2 7JP. Further details at Calvert22.org

Article originally published by The Calvet Journal on 04/02/2016