Memories of the Poisoned River

About Memories of the Poisoned River exhibition, by Kiluanji Kia Henda (Angola) and Felix Shumba (Zimbabwe and Sout Africa), in Luanda.

vista da exposição no Museu de História Natural, Luanda

vista da exposição no Museu de História Natural, Luanda Entrada da exposição na Jahmek Contemporary Art, Luanda

Entrada da exposição na Jahmek Contemporary Art, Luanda

***

Kiluanji Kia Henda and Felix Shumba’s exhibition, Memories of the Poisoned River, is a multimedia story of the rise (and prophesied fall) of extractivism, reflected through the prismatic lens of a river.

A river is a body of water that unites other bodies: plants, animals, and humans. A river is a body on a journey: over the course of millennia, she dances to the sea, carrying a procession of seeds and alluvial earth in her wake. Her children – ecologies and cultures – gather, grow, and thrive in her embrace.

If the care a river shows to the world is returned in kind, she may live a long and healthy life. Over the course of this life, she sees things, learns things, and imparts her knowledge upon all who care to listen. A river’s story is also our story; the song she sings is also our song. We might say that a river’s past is a lens onto our future and that the death of a river foreshadows our own demise.

The river remembers the arrival of extractivism. One day many years ago, she feels the wake of huge ships against her current and became uneasy. Over time, she comes to share shivers with felled forests, to balk at the blanched palette of monocrop agriculture, to recoil at the sharp poisonous taste of chemical waste, and to deeply mourn the disappearance of her people: people sold into slavery, killed by disease, worked to death in mines, and severed from her nurturing flows by the breaking of their cultures. Oh, what she has seen. Oh, what she has endured.

The river knew from those first moments that extractivism was more than the systematic removal of mineral resources from the body of Earth: It was a new a cosmology, a worldview, a way of being, forced by European colonists upon Africa and the world. The agents of extractivism claim that existence can be accumulated, but first it must be conquered and divided into parcels of private property. And so, extractivism segregates human beings from our wider ecological bodies, and segregates Black humans from the body of humanity. The river’s children come to see her as an other, and an object.

Through it all, the river watches: As borders drawn from afar hold existence in their crosshairs. As places once known for their more-than-human histories are renamed for their conquerors and reorganized according to their market value. As deposits of black oil and rare minerals are united in Euclidean geometries and uncanny constellations are formed of holes bored into the earth. As rivers and peoples are divided against themselves by Cartesian grids and communities are mutated into workforces. As humans blinded by bling lock their gazes to diamonds on the soles of their shoes and forget to hinge their dreams on the stars above. As the riverine reflections of the stars are occluded by industrial pollutants and humans come to forget her, forget them, and forget their selves.

As the river meanders here and there across time and place, she meets her lost children, mutated almost beyond recognition. Nocturnal Bodies recalls a time when she encounters a herd of horses. Their eyes burn with the phosphorescent traces of a chemical that has stripped their flesh to the bone. Their emaciated condition is echoed in Terra Esfolada – the eroded body of the earth. Earth’s womb – the home of our ancestors – is exposed and made barren. The womb becomes the Boca de Inferno – the maw of hell. Through her pain, the red earth smiles with golden teeth.

The river recalls how, in human antiquity, gold teeth were devised as medical solution to dental rot. Once the rotten tooth is extracted from the mouth, gold extracted from the earth is implanted in its place. Gold was chosen for its purity: it would never corrode, would never corrupt, would not leach toxins into the bloodstreams of its wearer. Yet poisonous chemicals are required to segregate pure gold from ore. Cyanide leaches into soil, into water, and, from there, into all of our bodies.

One day, a demon emerges from a Charred Still Life of felled trees and says to the river: While I dig into the darkness of the earth, I can see the bling of death in your eyes. Stunned into a trance, specters of Portuguese colonialism float past her mind’s eye. In the mines, diamonds are the only innocents. Stealing a diamond bears the same penalty as murder, and the thief who struggles to feed his children is hunted for sport. The worker with the labored breathing of diamond- studded tuberculosis is an externality. The critters caught in the crossfire are collateral damage. Extractive propaganda tells us that diamonds are forever. But Earth’s species, held in the sniper’s scope of a Diamond Cut Life, face extinction.

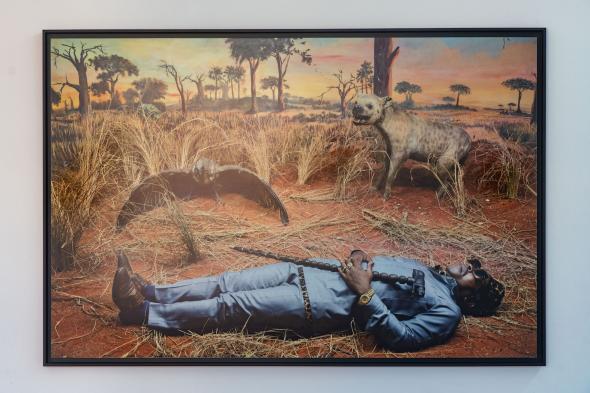

The river watches as the ghosts of her children gather the remains of their nonhuman kin, pump them full of formaldehyde, and arrange them in replicas of destroyed landscapes caged by glass. Is that the shadow of sorrow in the glass eyes of the pensive water buffalo? Is that fear frozen in the gaze of the once- mighty cheetah? Or are these our own souls – our own futures – that we see reflected? Surely, we do not find solace in the thought that our undying bling may one day embellish the glass tombs of our remains.

As the river meanders toward the horizon, weighed down by heavy centuries of toxics, refuse, and memories, her pace becomes sluggish. She tires of this old story. Earth’s siren’s spell grows weary. The river refers us to The catalogue of carnivorous plants and their prey, which reminds us that Earth has trained the most discounted of phyla – warriors from the kingdom of plants – to file their fibrous teeth against their attackers. A Restless Landscape unsettled and ruined by development is reanimated with a trickster energy; half-hewn trees perch like a population at the edge of revolt. These forests once taught our ancestors to lay in wait among their crowns to attack slave traders lurking below. Earth is an archive of counter-offensive strategies.

From her deathbed, the poisoned river recollects a time before extractivism, a time when her children joined her in rituals of care and gratitude. She calls to them – to us – across the tides of time. If you remember nothing, remember this: Earth will defend herself by any means necessary. She only hopes that we will join her in resistance.

Imani Jacqueline Brown

Kiluanji Kia Henda e Felix Shumba, Restless Landscape, 2023

Kiluanji Kia Henda e Felix Shumba, Restless Landscape, 2023 Kiluanji Kia Henda, Post Mortem Nightmare, 2022

Kiluanji Kia Henda, Post Mortem Nightmare, 2022 Felix Shumba, The catalogue of carnivorous plants and their preys,

Felix Shumba, The catalogue of carnivorous plants and their preys,  Kiluanji Kia Henda, Esqueleto Luxuria, 2022

Kiluanji Kia Henda, Esqueleto Luxuria, 2022https://www.buala.org/sites/default/files/imagecache/full/2023/12/memori..." alt="Felix Schumba, Nocturnal Bodies (Horses), 2023

" width="590" height="393" /> obra de Kiluanji Kia Henda

obra de Kiluanji Kia Henda  Felix Schumba, Nocturnal Bodies (Head), 2023

Felix Schumba, Nocturnal Bodies (Head), 2023https://www.buala.org/sites/default/files/imagecache/full/2023/12/7_memo..." alt="Kiluanji Kia Henda, The red earth smiling with golden teeth, 2023

Terra Esfolada, 2008" width="590" height="393" /> Felix Schumba

Felix Schumbahttps://www.buala.org/sites/default/files/imagecache/full/2023/12/captur..." alt="Kiluanji Kia Henda, Utopia in the Burnt Land e While I Dig Into the Darkness of the Earth, I Can See the Bling of Death in Your Eyes, 2023

" width="590" height="266" /> Felix Shumba, Charred Still Life, 2023

Felix Shumba, Charred Still Life, 2023