Cannibal Museology. Escaping categories to disrupt technologies of conquest

In the introduction to her book ‘Cannibal Capitalism’ Nancy Fraser (2022) situates different meanings of ‘cannibalism’. The most common one is related to the practice of eating the flesh of one’s fellow human beings. This meaning almost automatically brings us into the racial and imperial context of conquest and colonization of non-European populations1, which were often accused of cannibalism and thus needed “civilization.” In contrast, rarely the Europeans regarded their “civilizing missions” as symbolic and physical cannibalizing of the non-European populations. Besides that, Fraser discusses a specialized meaning of ‘cannibalizing’ used in astronomy: “a celestial object is said to cannibalize another such object when it incorporates mass from the latter through gravitational attraction” (Fraser 2020, xiv). While the former meaning refers to the context of racial capitalism, the latter speaks to the idea of incorporating others into one’s own system through the means of domination. This incorporation is characterized by the inclusion through the elimination of its own prior existence. Both senses are highly relevant to my thinking about cannibalization as colonial and imperial practice of domination and the ethnographic museum as a space par excellence privileging the ingestion of alterity while simulating openness to it. In this article I am looking at cannibal museology through two major lenses.

First, through the lens of ‘humanity’ not as a dichotomic category but as a continuum containing a variety of possible intermediate forms. Second, the process of engulfing otherness as a form of giving it space in an institution like the ethnographic museum. Both lenses of analysis draw inspiration and are in dialogue with the work of Tiffany Lethabo King’s “Black Shoals” (2019) where she develops the grammar of conquest and making of flesh. Conquest is an overarching framework of analysis of the formation of the modern idea of ‘human’ that is being modified in the course of centuries of colonial ‘exploration’, Atlantic Slave Trade and subsequent colonization. Starting with the figure of Columbus, his ‘discovery’ of the Americas was the moment of institution of the modern notion of ‘human’ defined in the process of conquest which also means dehumanization of Black and Indigenous people. This paper takes the overall framework of conquest as an overarching understanding of dehumanization of the non-While peoples and creation of institutions supporting this form of knowledge production. Thus, this paper, echoes the museum as a cannibal institution of conquest together with the idea of ‘humanity’ being modeled to satisfy the needs of conquest. It looks at -inspired by the work of King - ‘the making of the human through the relation of conquest’ and Black and other ways of doing humanity through fugitivity and fungibility.

For the understanding of cannibalism, distinctions between ‘body’ and unmaking of the human into ‘flesh’, or ‘fleshly matter’ that exists outside of the realm of the body and, thus, humanity (King, 2019, 53);2 between “person” and “thing” are fundamental, as in the vast continuum between ‘human’, ‘lesser human’, ‘non-human’ and/or ‘inhuman’. King emphasizes that within the discourse of conquest and genocide Black and Indigenous peoples represent a lesser version of the humanity, and are situated at the outer edge of humanity. They are incorporated in the larger category of the ‘human’ only to carry the burden and destiny of being lesser beings that live in the proximity to genocide and enslavement (King, 2019, 80).

Material and bodily relations and interactions are of fundamental importance for framing cannibalism of the technologies of conquest and of ethnographic museums specifically. The museum instead is not seen as an institution but as part of the bigger continuum of conquest and it’s embodiment by the Western powers. The body is not seen as a monad, as a discrete and spatially limited category, but as a source, a force and an opportunity, as a site of otherness within oneself but also as limited by difference. The category of ‘humanity’ is critically approached as a porous and open subject in opposition to fixed categories of modernity. The ethnographic museum feeds on the modern idea of the division between human and nonhuman, radically cutting off the original contexts and ideas of worlds that live and think differently. Instead, in Amerindian cannibalism the other is human and is seen as a source of knowledge3, while the perspective of fugitive feminism suggests to stop trying to become “human” at all because ‘humanity’ is the central constitutive category of whiteness (Emejulu 2022). Shedding light on these approaches, the article aims to move the reader away from clear-cut categorizations and into the realm of opacity and fluidity of boundaries. This transition from narrow definitions prompts us to consider how to exist beyond the limits of human experience.

Thus, this paper takes a stance where it leaves the realm of the ‘human’ as it is conventionally imagined by the White modern sciences. ‘Human’ is not seen as a category but as a space of becoming, opening up to metaphoric and imaginary worlds as well. In this article, being interested in radically different ways of knowledge production, the focus spans from Tupinamba cannibalism as a form of knowledge production, to fictional and speculative forms such as shape-shifting and Earthseed described by Octavia Butler4. The paper brings two examples of this – Tupinamba cannibalism as a way to discard the possibility of the Cartesian boundary and the life and death of Saartje Baartman as an example of building this boundary and taking it into the museum as a space of conquest; I use other examples that go beyond and against this Cartesian boundary, as in the case of writings of Octavia Butler. Different parts of this paper relate to eating the flesh, exposing human bodies – dead and alive –, dismembering human bodies into organs imagined as museological objects and use of bodily transformations as coping techniques within the logic of conquest, in response to it and against it.

I. Cannibalism as knowledge production

Tupinamba cannibalism

Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s writings on cannibalism have focused on its relational perspective. In the Amerindian context cannibal consumption can be defined as any devouring (literal or symbolic) of the other as a person in its (raw) condition—a condition which is the default value (Fausto 2007)5. Much of the work by the Brazilian anthropologist is dedicated to Tupinamba cannibalism that represents a system for socializing the enemy and cannot be limited to the consumption of the enemy. It consists of a very elaborate system of capture, execution, and ceremonial consumption of enemies in the context of warfare. Enemies very often were not as different from the captors because often they shared the same language and customs. The captivity represented a prolonged period of time during which the captive lived with their captors and ‘integrated’ into the community. The captives were also given spouses and were transformed into brothers-in-law. The same term, tojavar, meant in ancient Tupi both “brother-in-law” and “enemy,” its literal sense having been “opponent” showing how predation and affinity are closely linked in the Amerindian context. The cohabitation of the captive with the captor community was not comparable with the life of prisoner but was more similar to living in freedom under the watch of their captors while the long preparations for the execution ritual were being undertaken. Before the execution it was important to be sure that the other they would kill and eat was fully defined as a man, who understood and desired what was happening to him (Viveiros de Castro 2011, 61). It is equally certain, however, that the Tupinamba did not devour their enemies out of pity, but for vengeance and honour (ibid.). Tupinamba exocannibalism6 as described by Viveiros de Castro was built on the relationship with the other, in which the incorporation of the other required an exit from oneself - the exterior was constantly engaged in a process of interiorization, and the interior was nothing but movement towards the outside.” (Viveiros de Castro 2011, 46).

Tupinamba cannibalism is based on the circular relationship of vengeance, a complex and very symbolic series of relations between the captor and the captive but also between the captor’s community and the captive’s community where vengeance is the reaction to killing. Death in foreign hands was considered an excellent death because it was a death that could be vindicated, that is, a justifiable death and one capable of being avenged; a death with meaning, productive of values and people” (Viveiros de Castro 2011, 62). The death of the captive is not the end but actually the opposite: it is bringing future into being. Dying in the enemy’s hands means that the dead members of the group were the group’s nexus to its enemies (Viveiros de Castro 2011, 71-72). Vengeance is an endless – interminable – process, it is a machine to produce time. Without vengeance, that is, without enemies, there would be no dead, but also no children, and names, and feasts. Thus it was not the recuperation of the memory of the group’s departed that was in play, but the persistence of a relationship with enemies” (ibid). This way Viveiros de Castro interprets it as a movement forward and not as a step back: “the memory of past deaths, those of one’s group and those of the others, advanced the production of becoming” (ibid). A memory, in turn, that was nothing other than relationship to the enemy through which individual death placed itself in service to the long life of the social body. Hence the separation between the individual share and the group share, the dialectic of shame and offense: to die in foreign hands was an honour for the warrior, but an insult to the honour of his group, and it imposed the requirement of an equivalent reply” (Viveiros de Castro 2011, 63).

The essential part in the relationship between communities through the consumption of the members was relationship to each other. The honour of vengeance was in the role of the captive to serve as a victim, as a motive for vengeance, as a reason to continue the cycle of vengeance. Vengeance and underlying hatred are also signs of mutual indispensability of communities. Immortality was obtained through vengeance, and the search for immortality produced it. Between the death of enemies and one’s own immortality lay the trajectory of every person, and the destiny of all” (Viveiros de Castro 2011, 64). This relationship means also one of the crucial features that Viveiros de Castro emphasizes: a radical ontological incompleteness expressed by vengeance. This type of relations between community emphasized the absolute necessity of an exterior relation, or the unthinkability of a world without Others” (ibid).

Viveiros de Castro underlines that the essential ontological incompleteness of Tupinamba philosophy stands for the incompleteness of sociality, and, in general, of humanity. It was, in other words, an order where interiority and identity were encompassed by exteriority and difference, where becoming and relationship prevailed over being and substance. Viveiros de Castro coined the term “indigenous multinaturalist anthropophagy” to link the practice of cannibalism and the way of knowing the enemy’s point of view (Viveiros de Castro 2011, 65). This ritual consumption was a process of the “transmutation of perspectives whereby the “I” is determined as other through the act of incorporating this other, who in turn becomes an ‘I’ … but only ever in the other-literally, that is, through the other” (Viveiros de Castro 2011, 101). Seen from this perspective, cannibalism reveals itself not as a process of physical elimination and radical desubjectification but as a process of knowing, as a form of indigenous anthropology. For this type of cosmology, others are a solution, before being – as they were for the European invaders – a problem (Viveiros de Castro 2011, 47). The opponent’s humanity was fully recognized and never negated, nonetheless the hatred for enemies and ritual execution were integral part of the cannibalism complex (Viveiros de Castro 2011, 82). Recognition of the enemies’ humanity is at the basis of their approach to the other: “Their hatred of their enemies and the entire captivity/ ritual execution/cannibalism complex, were founded on an integral recognition of the opponent’s humanity—which has nothing to do, of course, with any sort of ‘humanism’” (Neves Marquez 2014).

The comparison with the European anthropology becomes very handy. While the European anthropologists and /or missionaries tried to interpret the indigenous point of view through the their own conquistador humanism, the indigenous anthropophagy presumed as vital condition the taking of life through eating to access the enemy’s point of view. “Incorporation of the other required an exit from oneself—the exterior was constantly engaged in a process of interiorization, and the interior was nothing but movement towards the outside. […] The other was not a mirror, but a destination” (Viveiros de Castro 2011, 46-47).

Cannibalism is a social way to approach otherness, to establish necessary (and unavoidable) social connections and to deal with the radical ontological incompleteness of being. In Amerindian perspectivism7 the major distance from the modern epistemology is the process of subject-making: it is the perspective that creates the subject and not the subject that creates the object or the point of view (Neves Marquez 2014, 300). Through the exchange of perspectives and the circular relation of vengeance, Tupinamba cannibalism is a sort of inter-scalar vehicle that connects the present and the past, making the future possible and opening it (Hecht 2018). In this case cannibalism is not only a bridge between different temporal dimensions but also a way to build communal memory. The Other – although ritually consumed – is never deprived of the humanity.

Interlude I

Eating flesh as a way to deal with ontological inconsistency is emphasized in the writing of Octavia Butler and in particular in the Patternist series. The first novel of the series, ‘Wild Seed’ is situated first on the African continent and then in North America where two immortals – Doro and Anyanwu – meet. Both characters embody malleable external forms capable of altering their outward appearance.

Doro is an immortal being who occupies bodies of others by killing their consciousness and using or ‘wearing’ their exteriority for some limited period of time. While Doro does not possess a body himself, he is able to take on bodies of persons he kills. Anyanwu instead has her own body but also has an ability of shapeshifting that allows her to take the form of a dolphin, of a bird or anyone else by ‘getting to know it’, ‘reading the message’ inscribed in its flesh. Anyanwu is able to read flesh as a message, as a book, as she says herself. This allows her to assume that exteriority but it also tells about the type of knowledge she receives from it: “It seems that you could misunderstand your books,” she said. “Other men made them. Other men can lie or make mistakes. But the flesh can only tell me what it is. It has no other story.”

The messages sent with the flesh and received by Anyanwu are ‘clear’, they are transmitted from the flesh of the animal directly to the flesh of Anyanwu, lacking the social and political components of knowledge sharing and production, avoiding any sort of misinterpretation.

“Did you have to eat leopard flesh to learn to become a leopard?”

She shook her head. “No, I could see what the leopard was like. I could mold myself into what I saw. I was not a true leopard, though, until I killed one and ate a little of it. At first, I was a woman pretending to be a leopard—clay molded into leopard shape. Now when I change, I am a leopard.”

When Doro takes Anyanwu to North America on a slave ship, at some point of the journey Anyanwu assumes the form of a dolphin. This symbolically connects her to the history of the Middle Passage and in particular to those slaves who were thrown overboard by slave traders, and also to the speculative history of Drexciyans inhabiting the ocean (Hameed 2014). This is also her way to overcome the Cartesian boundary between humans and non-humans that was at the basis of the Slave Trade and of the technologies of the conquest. This way Anyanwu opens up new routes for imagining the human, as part of the complex ecology connecting living beings.

Anyanwu’s relationship to change is inclusive of both body and mind. Once taken the form, she starts to act and think as a dolphin or as a leopard. Anyanwu’s approach abolishes clear boundaries between bodies, between species, between humans and non-humans. This is clearly stated in her words but also in her practice. This opposes her view to the modern episteme because it prevails flexibility, fungibility and shapeshifting as its main signs.

II. Boundaries. Saartjie Baartman

What for the Amerindians was a source of knowledge and a ‘destination’, for the European colonizers was a clear-cut boundary and a confirmation of their superiority upon which was based the idea of the subjugation of the other. Imperial conquest and colonization have been a violent both physical and epistemic processes that sustained and empowered the Western model of knowledge production: reducing the person, the animal, the species to understanding through the lens of white supremacy. The categories of the modern thought were formed and shaped in the light of the colonial enterprise and the affirmation of the European supremacy. One of a well-known and documented cases is the life and death of Saartjie Baartman who was not the first African to be exhibited in Europe but she was one of the first to become an “object” at once of entertainment, media interest, “sexual fantasy,” and racial science. After her death, her body was reduced to an object in the ethnographic museum, thus illustrating different phases of Western modernity’s relationship with the “unknown.”

Life and death of Saartjie Baartman.

Saartjie Baartman was buried on August 2002 in a national ceremony in the presence of the South African president, Thabo Mbeki after months of negotiations between South Africa and France. The trajectory between the birth of Saartjie Baartman, her travel to Europe, the first exposition in London in 1810, the death in Paris in 1814 and burial in 2002 is a long continuum of racial violence and what Denise Ferreira da Silva calls ‘the wounded captive body in the scene of subjugation” (Ferreira da Silva, 2022). After her physical death her body became a laboratory for racial science and lived as a specimen and as a museum exhibit.

Baartman is very often presented as an “object”, as a captive body in the story related to the development of ideas and scientific racism, even though we know a lot about her life and should see her as the main protagonist and the subject of her own story. Her story gives the possibility to look at her as a subject, as a woman, as well as a clear example for the violence of scientific racism. By re-establishing the connections between the living person and the world she lived in, it becomes feasible to link the abuse of Saartjie Bartman as a captive body with her uses as a metaphor, as a Cartesian boundary between ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ that was instrumental to the European society and science. Saartjie Baartman is at the same time a historical person as well as a metaphor as well as an illustration to the history of ideas (Derbew 2019).

As the majority of Khoisan in the colonial period, Saartjie Baartman was very likely a slave or her position in Cape Town was an unfree one. She was brought to the Cape by Dutch farmers after her father was killed (Qureshi 2004, 235). Before her departure to Liverpool and London in 1810, she worked as a servant for Peter Cezar. Her bodily trajectory takes her from Cape Town to Liverpool and London in 1810, staged by Alexander Dunlop, exporter of museum specimens from the Cape. Her trip to England should be seen in the framework of traffic of animals, plants and people destined for display as objects representing colonial expansion and as means of economic gain (ibid).

In London Saartjie Baartamn was presented by her owner as Hottentote Venus in a show where she personified a ‘wild’ woman mixing up exotic, grotesque and erotic (Blanckaert 2013, 7). As shown in the 2010 film by Abdellatif Kechiche her costume was made of such a thin and adherent material that it could seem she was naked. She was placed in the cage, wearing African beads and other ‘features’ emphasizing her ‘Africanness’. At the end of the performance, the public could touch her to verify that she was ‘real’.

Cesar’s chosen display outraged some members of the anti-slavery lobby. Although the British Empire had abolished the slave trade in 1807, but not slavery itself, keeping women in a cage was deemed scandalous by abolitionists who were horrified by Baartman’s mistreatment. During the court hearing, it was investigated whether Baartman displayed herself of her own free will or whether she was enslaved. According to the court paraphrase of the interview, she said that she stayed in London to earn money. Although she was often uncomfortable because of the weather conditions, she wanted to remain in England until it was time to return to the Cape. The court of the King’s Bench ruled that Baartman was a free person. Her employers were prosecuted for holding Baartman against her will, but not convicted, with Baartman herself testifying in their favour (Parkinson 2016). The proceedings ended, and the show of the Hottentot Venus continued for a number of months in London before moving to the provinces and then to Paris (Scully and Crais 2008).

Saartjie’s manager took her to France in September 1814 and sold to an animal exhibitor Jean Réaux (Upham 2007). Saartjie Baartman lived in Paris starting from September 1814 until the last days of 1815 when she died. In Paris, Baartman’s promoters did not need to concern themselves with slavery charges. There her existence was miserable and extraordinarily poor. There is some evidence suggesting that at one point a collar was placed around her neck (Sculy and Crais 2008, 301-323).

Baartman’s presence in Paris provoked interest also among so-called scientists. In fact, in the spring of 1815 Baartman agreed to be studied by professors of Museum of Natural History but declined to pose naked to them arguing that this was beneath her dignity. This was the beginning of what became known as “racial science” (Parkinson 2016). Saartjie Baartman died in late December 1815 of the illness diagnosed by Georges Curvier as “une maladie inflammatoire et eruptive”8.

Post-mortem life of Saartjie Baartman

After her death, Saartjie Baartman’s body was transported to Jardin des Plantes for the autopsy, dissection and preparation of the plaster cast of the body. The dissection was performed by Georges Cuvier (Magubane 2001, 817) who earlier attempted to study Saartjie Baartman naked. After her physical death he had full access to the body and published a detailed account of Baartman’s anatomy. The same autopsy and the report that was produced was guided by a will to draw a dividing line between ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’, as well as a straightforward expression of the colonial dehumanizing arrogance towards ‘colonized’ and the decision to act on the body as if it was a thing (Gilman 1985, 213). Georges Cuvier dissected her corpse in the name of science and immortalized her as a biological specimen. In his report Curvier discussed the humanity of Baartman presenting her as an inferior human form.

Cuvier preserved her skeleton and pickled her brain and genitals, placing them in jars displayed at Paris’s Musée de l’Homme until mid-1970s. Besides that, Cuvier made several casts of Saartjie Baartman’s body and a wax cast of the tablier. Both the skeleton and the cast were displayed in the halls of the Musée d’Histoire Naturelle along with two other human skeletons and numerous other objects until 1974 (Qureshi 2004, 245; Parkinson 2016). The plaster cast of the body remained in the hall of the Musée de l’Homme until the mid-1970s when it was removed (Blanckaert 2013, 445-45).

Removal of the skeleton and apparent reconsideration of the role of museums may seem like a positive development to some, but it fails to problematize museum space as an institution of conquest, as a space of manifestation of colonial ambition. The museum still privilege the master narratives, nominally extending the category of the human rather than completely revising it. While the continuum from ‘human’ to ‘lesser human’ and ‘non-human’ is questioned, it is revised within the technologies of the conquest still relating to the modern dichotomies like human/non-human, private/public, etc (Palmer 2023).

During the funeral of Saartjie Baartman, South African president Thabo Mbeki maintained that “The story of Saartjie Baartman is the story of the African people…. It is the story of the loss of our ancient freedom … [and] of our reduction to the state of objects who could be owned, used and discarded by others”. Seen in its full duration, from the birth until the burial after 185 years from her death, the life and death of Saartjie Baartman can be seen as a chronology of a change in knowledge production in the framework of the conquest, from the cabinet of curiosity to the museum.

Interlude II. Taking the floor / Red Peter

In the movie by Abdellatif Kechiche ‘The Black Venus’, the personage of Saartjie Baartman speaks in front of the courtroom full of audience. According to the court paraphrase of the interview, she said that she stayed in London to earn money. Although she was often uncomfortable because of the weather, she still wanted to remain in England. The court of the King’s Bench ruled that Baartman was a free person. ‘Freedom’ and ‘free’ are the key concepts linked to the human condition in the West, imagining that those who are humans are free and exercise their rights as free persons. A similar scene, although not in a courtroom, is depicted by Franz Kafka in the short story ‘Report to an Academy.’ An ape that became human reports his experience. As Red Peter puts it himself, the main feeling he had when he was a caged animal was: no way out. His following observation is very meaningful: “Of course what I felt then as an ape I can represent now only in human terms, and therefore I misrepresent it, but although I cannot reach back to the truth of the old ape life, there is no doubt that it lies somewhere in the direction I have indicated.” (Kafka 1983). For Red Peter becoming human was a way out from his condition of the caged animal. Red Peter explains very clearly the need to become human: the caged animal does not have a choice. He also states that he did not want freedom (in the human terms) but he needed a way out which was for him becoming human. As a result of careful observation, Red Peter understood that his way out was making his way to variety stage where he exhibited himself to earn money. The same choice that Saartjie Baartman made.

III. Human bodies in the museum // Museum as a cannibal institution

From Wunderkamera to human zoos and ethnographic museums: seeing – exhibiting – institutionalizing the difference.

A continuum from freak show to anthropo-zoological exhibitions (Blanchard et al 2008) is a trajectory of technologies of conquest (King, 2019, 77)9 and of rationalizing alterity through the human/Other dichotomy and in particular whiteness as it’s constitutive element (Blanckaert 2013, 48-49). Each major Western imperialist power used Exhibitions10 to showcase differences and legitimize their conquests overseas (Blanckaert 2013, 48-49). The very process of constructing the abnormality of the Other was constitutive to the process of normalizing whiteness. Exhibiting the other became a symbol of colonial grandeur, capacity to conquest and a symbol of modernity. For colonial powers, the ability to display otherness was also a way to distance themselves from the other and assert their own “normality” and superiority.

The colonial representational practice initially concerned small aristocratic circles of privileged public. In the 19th century both public and scientific interest toward “specimen” grew and started to include world’s fairs, spectacles, circuses and theatres. In that period, the exhibition of living foreign peoples were accessible and highly profitable forms of entertainment (Qureshi 2004, 238). Public interest in these shows was stimulated by a range of factors including ethnic “singularity”, physical peculiarities and the subjects’ political relevance as Britain’s colonized subjects or military opponents. In this context, the show with Saartjie Baartman became somewhat of a watershed case and symbolically divided Europe’s approach to Otherness. Some authors even suggest two different historical moments: “before Hottentot Venus” (1492–1789) and “after” (1840–1940) (Boëtsch and Blanchard 2008, 188).

The fascination with monstrosity is closely linked to the devaluation of forms of difference (Blanckaert 2013, 51). These spectacles played an important but often overlooked role in the development of anthropology before it became a professional discipline and before the advent of fieldwork as a form of ‘data collection’ (Lyons 2018, 333). Later, ethnographic museums were central for shaping the dividing line between ‘us’ and ‘them’. Starting in the mid-19th century, human zoos were supplemented by temporary exhibitions of people from colonised territories at world trade fairs. These fairs were designed to showcase opportunities in extractive and plantation industries, as well as manufacturing and technology. The ‘native’ populations served both as a spectacle to attract visitors to the pavilions and as symbols of investment potential.

Ethnographic museum

A spatio-temporal capsule of ethnographic museum brought forward and continues to bring forward hierarchical approaches to humans and others11. As discussed above, situating some humans as lesser humans is a common trope for the representational trajectory of Western logic of conquest and genocide, visible in the ethnographic museums since their creation12. Treating human bodies as museum objects stripped of their humanity was one of the hallmarks of racial science and consequently, of the ethnographic museum.

Ethnographic museums or museums of natural history collected, stored and exhibited “human remains” until there were numerous requests for restitution and burial of the bodies. In September-October 2011, Charité Medical University, Berlin, started to return human bodies despoiled during the colonial war in Namibia for scientific research in Germany to Windhoek. The significance of the repatriation of bodies was marked by a protracted struggle for the acknowledgment of genocide in Namibia (Eriksen 2005; Zimmerer and Zeller 2008) and the acknowledgement and the status of these remains as well as the respect and dignity they deserve to be treated with (Förster and Fründt 2017). The first return from a German institution was followed by the repatriation of thirty-five bodies from Charité and Freiburg University in March 2014. The restitution process has been linked to the requalification of “institutional objects” into “human remains”, a significant step seen as a response to requests from communities around the world. This is one of the actions contributing to the inclusion of more human beings in the category of “human” as viewed by Western institutions. The Namibian delegation reframed the remains as “ancestors” shifting the attention from “dead” to the relational and human aspect of these bodies (Biwa 2017, 92). In fact the same term “human bodies” “interrogates how bodies were instituted as non-human through a process of translation and became “remains” in archives through various disciplinary procedures of disavowal” (ibid, 91). This is particularly significant with the display of bodies that were colonized or exterminated as in the case of the Namibian genocide. The gradual extension of the category of ‘human’ emphasizes the crucial role of categorizing and hierarchizing that modern and colonial institutions have at their basis for the justification of their existence. This is particularly relevant in the context of colonial violence and racial science that guided the whole principle of hierarchical and classificatory approach to the world. Thus, repatriation of remains of humans was also a way to signal the epistemic shift in human vs non-human relationship established by the colonial science and colonialism and enacted by the ethnographic museum as an institution. This change of the approach to human bodies can be seen as a long continuum from dehumanization to recognizing humanity, as a way to reconsider the ontological status to some beings as a response to changing political environment.

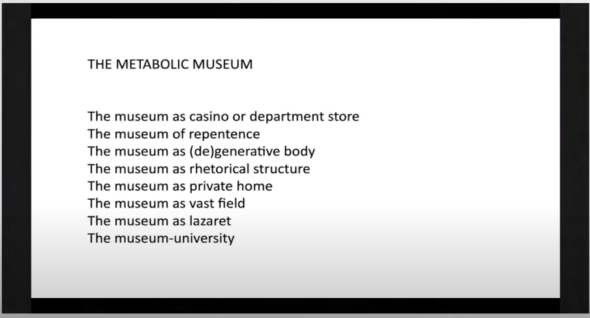

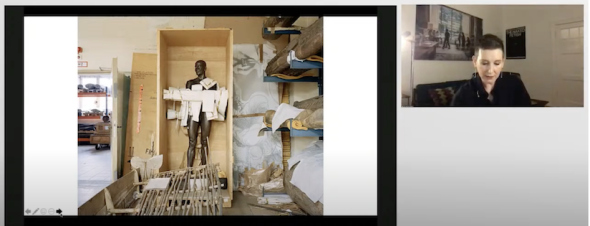

Digesting difference: cannibal institution

During her online lecture for S.M.A.K., Clementine Deliss presented her research on Metabolic Museum (Deliss 2020) and different articulations of ethnographic museum (see Image 1). She refers through a series of metaphors to museum as a space of repentance, as a rhetorical structure and as (de)generative body. Using an example of a photograph shoot by Armin Linke (Image 2), she refers to a brutality of the relationship between human and non-human matter in the museum, as well as physical and material traumatic history in and of the museums. Referring to the museum as a (de)generative body, it becomes easy to visualize how it enters into direct physical and material interaction with the «objects» meant to be displayed. Besides, this is a different stage of the physical contact after the initial phase of fieldwork. These different forms of proximity are used by the racial science as a testimony of knowing while at the same time are characterized by ‘describing, naming and exploiting’ (Biemann 2022, 40).

Clémentine Déliss’s metaphor helps to imagine the interaction between the incoming objects and the institution through the prism of physiological processes. Like a living organism, established to enact some of the technologies of conquest, the museum swallows the object that is brought into its premises. Passing through the mouth, the object follows its path through the digestive system where it is literally assimilated, that is, stripped of its ties, connections and histories. Although this metaphor gives the idea of a close encounter, it has nothing to do with the relational encounter between minds or entities (ibid). The result of this digestive process is defecation/excretion: the object digested by the museum system is the discharge of the modernist system brought to light through its display – it is what we see in museum vitrines. These ‘naked’, ‘solitary’ objects that refer to the reality constructed by western anthropologist and has little to do with the original object. Such a ‘production’ of anthropological knowledge, or formatting of Others according to the standards of the never-ending colonial project was termed by Denise Ferreira da Silva (2007) as engulfment, a process metaphorically related to the voracious appetite of the universalism and the Western colonial project.

Image 1. Screenshot from the online lecture at S.M.A.K.

Image 1. Screenshot from the online lecture at S.M.A.K.

The digestion metaphor leads us back to the idea of cannibalism described by Eduardo Viveiros de Castro and cannibalism condemned by the European ‘explorers’ and colonizers. The Amerindian exocannibalism “projected a form in which the socius was constructed through relationship with the other, in which the incorporation of the other required an exit from oneself—the exterior was constantly engaged in a process of interiorization, and the interior was nothing but movement towards the outside. […] The other was not a mirror, but a destination.”( Viveiros de Castro 2011, 46). This movement towards the other opens epistemically new ways of thinking about difference, very different from the ethnographic museum’s approach that constructs the relationship with the other by incorporating it into the system (as in the second meaning of cannibalism used in astronomy (Fraser 2022, xiv). The ethnographic museum processed ‘Others’, stereotyped different populations and ascribed to them an understanding according to the norms and worldviews under modern imperial culture13. As stated by Rassool, the modern evolutionary museum that emerged as part of the ‘exhibitionary complex’ is a primary site of the formation and reproduction of empire. Such an approach and racial thinking laying at the basis of the modern thought, cannot be reduced to an error or a period in modern history (Ferreira da Silva 2007). It is a long continuum of conquest and making sense of what is encountered. It goes from seeing/looking to exhibiting and then institutionalizing difference within an ethnographic museum, a place that reflects the racial theories and the imperial ambition of the West. The exhibitionary complex includes as well the “digestive complex” that cannibalizes the Other, the differences and engulfs everything in order to produce a homogenized product situated hierarchically in the modern idea of the world. The digestion of the object in the museum is its adaptation to the Western system of the worldview.

Image 2. Kubai plaster-cast figure presumably representing a friend of the founding director of the Weltkulturen Museum, Frankfurt, date unknown, in the museum’s holdings.

Image 2. Kubai plaster-cast figure presumably representing a friend of the founding director of the Weltkulturen Museum, Frankfurt, date unknown, in the museum’s holdings.Keeping and exposing both objects and human bodies in the museum is a clear cannibalistic approach to human and non-human beings whose agency, intentionality and humanity are not only questioned but negated. The so-called ‘human remains’ go from body parts, to mummies, to entire bodies stored in the museums behind a variety of reasons. Reverting the imperial lens would mean changing the approach to cannibalism and seeing ethnographic museums as cannibalistic institutions aimed at digesting difference and reinforcing white supremacy. Linking voracious appetite of the capitalism with the exhibitionary complex and digesting of difference takes us to the question of the epistemic approaches to difference within the modern world. The repatriation of remains of humans intends to reform the established epistemological order, but it cannot just disappear. If the existing hierarchies are not undone, avenues for imagination and thought are not open. The search for these avenues and their envisioning is the central goal of feminist and more than human approaches that transcend the human as a category.

IV. Ontological distances

Does differences exist? What ‘difference’ actually means?

Although both Tupinamba cannibalism and the ethnographic museum represent ways of engaging with difference and its physicality, the great rupture is situated in the domain of relationality. The ethnographic museum, as an embodiment of the Western/modern episteme’s institutionalization, finds its foundation in the compulsion to catalogue, categorize, and designate, underpinned by the notion of truth or essence inherent in the objects. Here, the “essence” of objects or entities is delineated through the lens of western thought, often disregarding their cultural origins, or at most, conforming them to the “grid” of modernity. The possibility for the Other to bring a different categorization or further understanding is limited because the ethnographic museum relies on its ontological completeness and its dominant understanding of the world. In the case of Tupinamba cannibalism, however, the body of the Other is seen as different and it does not serve to provide confirmations, but as an extension of perspectives. Returning to the quote from Eduardo Vivieros de Castro already quoted above, the other is seen as a destination:

“The warrior exocannibalism complex, projected a form in which the socius was constructed through relationship with the other, in which the incorporation of the other required an exit from oneself—the exterior was constantly engaged in a process of interiorization, and the interior was nothing but movement towards the outside. […] The other was not a mirror, but a destination. […] Tupinambá philosophy affirmed an essential ontological incompleteness: the incompleteness of sociality, and, in general, of humanity. It was, in other words, an order where interiority and identity were encompassed by exteriority and difference, where becoming and relationship prevailed over being and substance. For this type of cosmology, others are a solution, before being—as they were for the European invaders—a problem” (Viveiros de Castro 2011, 46-47)

The imposition and exit from the boundaries of the body is also one of the central themes of the work of Octavia Butler who explores the imposed boundaries between self and the other, nature and culture, subject and object, putting emphasis on existing alternatives. Her work in some way can be brought to the general questioning of the nature of human, of the fact of being human and opening space for post-humanist critiques of the modern episteme (María Ferrández-Sanmiguel 2022).

As discussed in the Interlude I, Anyanwu’s shapeshifting is a form of denouncing of fixed, stable identities by opposing to it an evolving subject, a fluid relationship between beings inhabiting the Earth. It is a great example of asking the question of what can be considered self and what can be considered ‘the Other’, do they exist at all? King (2019, 104-110) refers to Black fungibility or the unending capacity of Black exchangeability used under conditions of capture, the hold and social death. A Black fungible subject disrupts the boundaries into the more-than-human dimension unfixing this space between beings opening it for relationship and transformation.

In her later work, in particular in the Earthseed series, Butler works on the worldview summarized in the statement ‘God is Change’. It is an ode to difference, change and opacity. As everything is change, and God itself is change, then there is nothing fixed, stable and constant. There are no dichotomic boundaries and pre-established categories. Such an approach can be considered as radically different from the modern episteme. If the ethnographic museum appears to be one of the dead ends of modern thinking, one way out would be to find a way to abolish the museum by getting out of the classificatory tunnel and finding a way to open up to uncertainty and to change as the only certainty.

Returning to the image of Saartjie Baartman standing in front of the court, Paul B. Preciado’s short book addressing the conference of the French Psychoanalytic Society comes to mind. Preciado compares himself with the Kafka’s Red Peter – an animal who underwent the transformation into a human being because that was the only way out from the condition of a caged animal.

Preciado himself speaks about the exit from the cage of a transman. He speaks of an impossible metamorphosis (Preciado 2021, 12), the transition as the process that actually defines the existence. While Preciado refers to the transition between normative genders, as a way of exiting one cage and entering another, his thinking is also very close to the ideas of liberation from the cage, the cage of the human, the cage of the species, the cage of self, as discussed in the previous sections. This exit is the way out from the normativity, it is an exploration of the world beyond the cage of imposed/fixed categories. Preciado speaks of a way out, the way out as it is for Anyanwu, as it is imagined in the case of Tupinamba cannibalism. It is a way to deal with imposed boundaries, it is a way of living in transition. Echoing the Parable of the Talents and the slogan “God is change,” Preciado affirms life as mutation and multiplicity. The vital logic of the way out, opacity, transition and multiplicity does not allow engulfment and opens paths for alternative routes not based on conquest and boundaries.

References:

Biwa, M. (2017). Afterlives of Genocide. Return of human bodies from Berlin to Windhoek, 2011 in Memory and Genocide: On What Remains and the Possibility of Representation, (eds) Fazil Moradi, Ralph Buchenhorst, Maria Six-Hohenbalken, p. 92.

Blanchard, P. et al. (2008). Human zoos : science and spectacle in the age of colonial empires, Liverpool University Press, Liverpool.

Boëtsch, G and Blanchard, P. (2014). From Cabinets of Curiosity to the “Hottentot Venus” A Long History of Human Zoos in The Invention of Race, New York, Routledge.

Blanckaert, C. (eds) (2013). La Vénus hottentote entre Barnum et Muséum, Paris, Publications scientifiques du Muséum.

Butler, O. (2020). Wild Seed. Grand Central Pub.

Deliss, C. (2020). The Metabolic Museum, Hatje Cantz /KW.

Derbew, S. (2019). (Re)membering Saartjie Baartman, Venus, and Aphrodite, Classical Receptions Journal, Volume 11, Issue 3, Pages 336–354, https://doi.org/10.1093/crj/clz008

Emejulu, A. (2022). Fugitive Feminism, Silver Press, London.

Erichsen, C.W. (2005). “The Angel of Death Has Descended Violently among Them”: Concentration camps and prisoners-of-war in Namibia, 1904–08 . Leiden: African Studies Centre.

Fausto, C. (2007). Feasting on People: Eating Animals and Humans in Amazonia. Current Anthropology, Vol. 48, No. 4 (August 2007), pp. 497-530 504.

María Ferrández-Sanmiguel (2022). Octavia E. Butler’s Posthuman(ist) Imagination, in Critical Posthumanism, available: https://criticalposthumanism.net/octavia-e-butlers-posthumanist-imagination/

Du Bois, W. E. B. (1903). The Souls of Black Folk. Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co.

Ferreira da Silva, D. (2007). Toward a Global Idea of Race. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Ferreira da Silva, D. (2022). Unpayable Debt, Sternberg Press.

Fraser, N. (2022). Cannibal Capitalism: How Our System Is Devouring Democracy, Care, and the Planet and What We Can Do about It, Verso Books, p. xiv.

Förster, L. and Fründt, S. (2017). Human Remains in Museums and Collections. A Critical Engagement with the „Recommendations“ by Redaktion H-Soz-Kult, p.1

Gilman, S. (2001). Black Bodies, White Bodies: Toward an Iconography of Female Sexuality in Late Nineteenth-Century Art, Medicine, and Literature. In Critical Inquiry, 12, p. 213.

Golovko, E. (2021). Visitors Protesting Against the ‘Museum of Others’ in Center of Experimental Museology, https://redmuseum.church/en/visitors-protesting-against-the-museum-of-others

Hameed, A. (2014). “Black Atlantis” in FORENSIS: The Architecture of Public Truth, ed. Forensic Architecture. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Hicks, D. (2020). The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution. London: Pluto Books.

Hecht, G. (2018). “Interscalar Vehicles for an African Anthropocene: On Waste, Temporality, and Violence.” Cultural Anthropology 33, no. 1: 109–141. https://doi.org/10.14506/ca33.1.05.

Kafka, F. (1983). The Complete Stories, Schocken Books, New York.

King, T. L., (2019) The Black Shoals. Offshore formations of Black and Native Studies. Duke University Press.

Lyons, A. (2018). The Two Lives of Sara Baartman: Gender, “Race,” Politics and the Historiography of Mis/Representation, Anthropologica, Vol. 60, No. 1, Thematic Section / Section Thématique, pp.327-346.

Magubane, Z. (2001). “Which Bodies Matter? Feminism, Poststructuralism, Race, and the Curious Theatrical Odyssey of the ‘Hottentot Venus’.” Gender and Society 15, no. 6.

Neves Marques, P. (2014). The Forest and the School. Introduction, Archive Books.

Palmer, L. (2023). “The Lichen Museum”, University of Minnesota Press.

Parkinson, J. (2016). The significance of Sarah Baartman, BBC, available on: https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-35240987

Preciado, P. B. (2021). Can the Monster Speak? Fitzcarraldo editions.

Qureshi, S. (2004). “Displaying Sara Baartman, the ‘Venus Hottentot.” History of Science 42 (136): 233–257.

Rassool, C. (2015). Re-storing the Skeletons of Empire: Return, Reburial and Rehumanisation in Southern Africa, Journal of Southern African Studies, 41:3, 653-670.

Scully, P. and Crais, C. (2008). Race and Erasure: Saartjie Baartman and Hendrik Cesars in Cape Town and London. The Journal of British Studies, 47, pp 301-323

Upham, M. G.(2007). From the Venus Sickness to the Hottentot Venus: Saartje Baartman & the 3 men in her life: Alexander Dunlop, Hendrik Caesar & Jean Riaux in the Quarterly Bulletin of the National Library of South Africa (QB), vol. 61, no. 1 (January-March 2007), pp. 9-22 & vol. 61, no. 2 (April-June 2007), pp. 74-82. Available at: https://mansellupham.wordpress.com/2019/08/13/from-the-venus-sickness-to-the-hottentot-venus-saartje-baartman-the-3-men-in-her-life-alexander-dunlop-hendrik-caesar-jean-riaux/

Viveiros de Castro, E. (2011). Inconstancy of the Indian Soul. The Encounter of Catholics and Cannibals in 16-century Brazil. University of Chicago Press.

Zimmerer, J. and Zeller, J. (2008). Genocide in German South West Africa: The Colonial War of 1904–1908 and Its Aftermath . Monmouth: Merlin Press.

- 1. For example, see the exhibition and the book published by Gonseth, Marc-Olivier, HAINART, Jacques et KAEHR, Roland, Le musée cannibale Musée d’ethnographie, Neuchâtel, Suisse, 2002,

- 2. In the reading of Spiller ‘flesh’ is seen as “pre-ontological and liberated space outside of enslavement” (King, 2019, 53).

- 3. For a detailed discussion, see the following section ‘Cannibalism as knowledge production’.

- 4. Earthseed is a fictious religion described by Octavia Butler in her novels ‘The Parable of the Sower’ and ‘The Parable of Talents’ based on the idea that “God is change.”

- 5. Noncannibal consumption supposes a process of desubjectifying the prey, a process in which culinary fire plays a central part.

- 6. Exocannibalism is cannibalism of persons from outside one’s family or tribe.

- 7. Perspectivism is a conception according to which the world is inhabited by different sorts of subjects or persons, human and non-human, which apprehend reality from distinct points of view.

- 8. an inflammatory and eruptive disease

- 9. In her book “The Black Shoals. Offshore formations of Black and Native Studies” Tiffany Lethabo King, analyzes the case of map-making as technologies of conquest.

- 10. The International Colonial and Export Exhibition in Amsterdam in 1883 or the so-called Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1878.

- 11. Dan Hicks develops the idea of compartmentalization through the idea of the museum as a space of containment. This containment is linked both to the idea of dehumanization of Africans and at the same time to the ‘normalization of the display of human cultures in the material form.’ For a detailed discussion see Golovko (2021) and Hicks (2020).

- 12. In the last decades the debates related to the decolonization of museums were very important. Due to space limitation it is not possible to illustrate them here but some publications should be mentioned Hicks (2020) and Deliss (2020).

- 13. “extractive, hierarchical and stratified relations of knowledge, and founded on disciplinary rituals of expeditions, fieldwork and collecting, as well as on appropriations of corpses, body parts, skeletal remains and artefacts between continents and across borders.” Rassool (2015, 653.