"Heart there and body here in Pretugal." In between mestizagem and the affirmation of blackness

Photos by Otávio Raposo

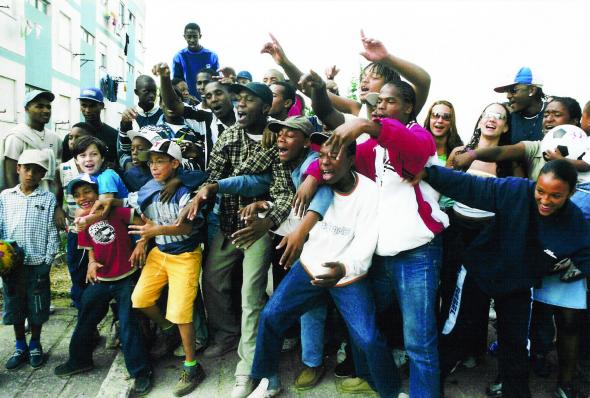

I set out to understand the modes of sociability of the Red Eyes Gang, a group of youths from Arrentela, Seixal, on the outskirts of Lisbon. The majority of them are children of African immigrants from countries that were formerly Portuguese colonies, and live in socioeconomic conditions well below those of the Portuguese. All were born in Portugal or arrived very young, never knowing their parents’ countries of origin. However, they appropriate some of their ethnic and cultural heritages because of the stigmatization and racism to which they are subjected, reworking their condition of being poor and black. They do not mechanically reproduce the way of life and ethnic influences of their families, but reinvent them with imagination, thus producing positive statements about themselves. It is in this sense that they adhere to the musical style of rap and create informal collectives, such as the Red Eyes Gang, both of which are spaces of self-affirmation that allow them to make up for the nonidentification of young people with Portuguese institutions (schools, associations, political parties, police, etc.). It allows devalued characteristics (being poor, black and living in a neighborhood with a bad reputation) to be viewed with pride and dignity, producing a positive impact on their self-esteem as well as alternatives of social inclusion in a context marked by the weakness of state institutions.

Lifestyles of the Red Eyes Gang

The Red Eyes Gang corresponds to a group of friends who live in the same neighborhood and take possession of its streets to socialize and share the problems, experiences and joys of youth. Despite the the word gang, this collective has no connection to crime, nor does it have any type of internal organization. It is an informal group, nonhierarchical, and lacking any rituals of admission or obvious signs of membership, which contrasts with the meaning of gang used by many investigations on the subject3. We consider the Red Eyes Gang a crew, and its creation is associated with media influences received from North American youth cultures linked to hip hop4. The crews are groups of young people who see themselves involved in common practices, in this case rap, and who come together under the same name. Its members, in most cases, have a strong attachment to territory, living in the same neighborhood and sharing the same lifestyle. Therefore, the creation of the Red Eyes Gang crew is the result of organizational affirmation of friendship within the group and the feeling of belonging to the neighborhood of Arrentela. It also allows a greater projection of the members’ music, acting as a badge of locally constructed identity.

Initially, the Red Eyes Gang was a very small group (no more than the 30 individuals), created following the formation of Arrentela’s first two rap groups of:187 Squad and Kombanation. However, more rap groups emerged (Bronxianos, RevelaSom, Defensores da Rua, etc.) in a period when this style of music was heavily circulated by the media. The relative prominence that some of these neighborhood rap groups have won in the panorama of Portuguese hip hop meant that more young people listened to rap music and, consequently, to the Red Eyes Gang. At the time we conducted field work (2005-2007), the number of youths belonging to the crew exceeded one hundred individuals.

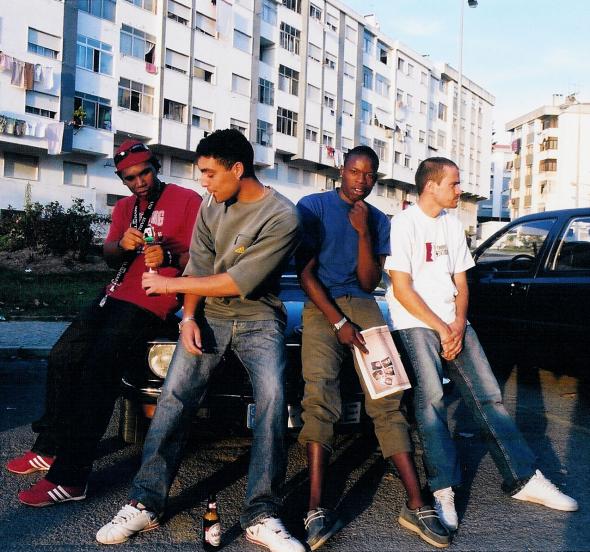

All the young people who comprise the Red Eyes Gang are poor and mostly black (African immigrant parents) with a significant presence of Portuguese whites within the group. The diversity of origins among the young blacks who are part of the crew is notorious (Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Sáo Tomé, etc.) and reflects the broad ethnic and cultural diversity of the neighborhood residents. Thus, the companionship established by the youths within the group is largely mixed, lacking any separation in sociability as to skin color or parental origins. We can find youths of various countries of African origin on the same street corners alongside young Portuguese whites, wearing the same type of clothing and accessories (earrings, rings and caps) and adhering to similar attitudes and lifestyles (slang, gestures, recreational preferences and music). Thus, ethnicity is not an impermeable boundary in building networks of friends in the neighborhood, nor is it a determinant in adherence to the Red Eyes Gang.

Although the practice of rap is the structuring activity of the Red Eyes Gang, it is not necessary to be a rapper in order to be part of the group. The set of shared experiences on the neighborhood streets determines the membership of this crew as much as adherence to a rap lifestyle. This is a major identifying component of the Red Eyes Gang, making up the formulation of a collective identification. Rap supplies the youth with information and performative material, which guides them in their daily lives to outline management strategies in order to meet the challenges they face. Language, musical and aesthetic preferences, body ornamentation, options for leisure or focal and ritual activities (Feixa, 1999) are some of the many elements that unify the lifestyle of these young people, creating a “narrative of self-identity”(Guiddens, 1995:75).

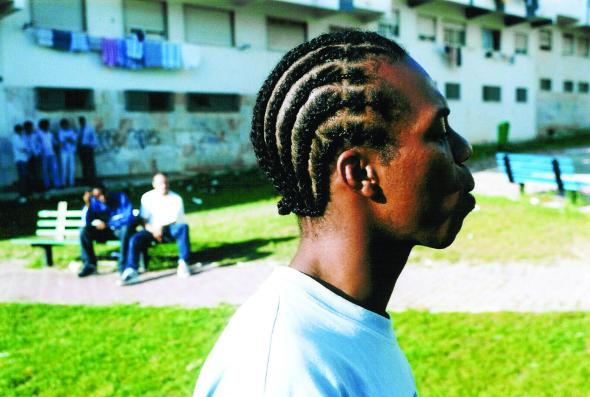

The influence of rap can easily be seen in various African-inspired hairstyles (braids, dreadlocks, etc.) and in their sportswear and street wear: shirts with symbols and letters associated with youth culture in the U.S., jeans and other pants, oversize hooded jackets, soccer uniforms, brand-name tennis shoes (Nike and Adidas are the most common), head scarves and hats and various accessories (earrings, necklaces and gold or African seed bracelets). The slang and use of Creole as a common language among them, as much as certain attitudes and behaviors, not only expresses sociability in the style of alternative rap, but promotes membership in and integration to an affective community, in this case the Red Eyes Gang.

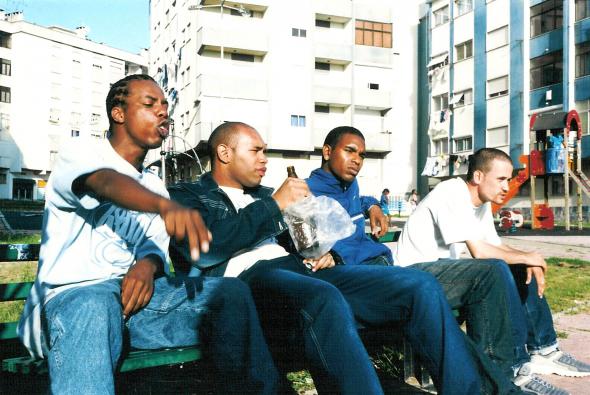

The identification with the “adult world” (school, work, political institutions) and lack of space to express themselves incites the youth to join youth styles in which they themselves are the protagonists. In this sense, adherence to rap and the Red Eyes Gang legitimizes their claim on their own ways of being young, making the streets of Arrentela the stage of their sociability. So rapping in public spaces, laughing and talking loud at night on the streets of the neighborhood, driving cars at high speeds through the neighborhood or smoking hashish are rituals of disobedience to adult rules, and foster a particular subjectivity. They are symbolic manifestations of the usufruct of the right to youth, and they attempt to thwart a subordinate status which hinders their leisure practices. While they enjoy themselves, they orchestrate a “choreography of friendship” that celebrates the bond between them (Alvito, 1998:195). Therefore, the Red Eyes Gang’s rap style cannot be reduced to a mere aesthetic appeal, as it influences the behaviors and attitudes of its members. It produces symbolic and ideological content that attempts to provide answers to the anxieties and difficulties of their daily lives. Simultaneously, it is used by the young crew as a way to change a status of inferiority by deconstructing the discourses that associate them with violence, passivity and poverty through rap. Therefore, for the Red Eyes Gang, rap can be understood as the main language for interpreting the reality around them, rebelling against a society that devalues them.

Through rap, these youths exercise the “power of the word” and assert themselves as active creators who can express themselves to their peers and society as a whole, breaking barriers in an “autistic” way, disinclined to pay attention to them. The word fills and provides hope to a life that no longer makes sense, recuperating cultural and ethnic references that are important to them, and at the same time denouncing a life of oppression. These issues were expressed by Chullage, a rapper who plays a strong leadership role within the crew:

You in a classroom don’t have the right to express yourself; in court you don’t have the right to express yourself; at a job interview, you don’t have the right to express your way of speaking, your gestures. They’re going to say that this isn’t according to rules of EU communication, when you’re like that. We have this life. On the news or on television, you don’t have space to express yourself, you didn’t have any space. And rap music created a space that brought all of this. Rap informed the people in the neighborhood, educated the people, and at the same time entertained the people. It joined several things into one, it was a bomb. At that time you processed it, “Ooh man! I can speak for my niggaz with rap, make them dance, make them listen, make them learn, get them to mobilize themselves for certain causes.” And at the same time, other people’s rap was making me do that too, it was a simultaneous process. I was learning from the rap of others and was transmitting information with my rap. It was a scene that motivated me man, a space that wasn’t found anywhere else in Portugal, not in the media, not in school, not on the street. It was the opportunity to make your own CNN, as Chuck D said, your newspaper, your education, and this was spread to other neighborhoods.

[Chullage in the film NU BAI - Lisbon’s black rap, 2006].

In the absence of adequate institutional frameworks to support them in managing their processes of identity and life projects, the importance of being part of the Red Eyes Gang is enormous. On the one hand, it increases its members’ self-esteem, promoting a positive image of themselves beyond the discourses that represent them negatively. On the other, it reworks the meaning of being young (poor and black) in Portugal, allowing them to be seen from the perspective of the qualities they possess. According to this view, belonging to the Red Eyes Gang allows them to be successful as members of a respected crew that operates in the public arena through rap music, denouncing injustice, claiming rights and demanding better living conditions. Therefore, the group operates as a creative and valuable resource for social integration for its followers, giving the feeling of being part of an “imagined community.” (Anderson, 1983)

The creation of the Red Eyes Gang not only enables these young people to collectively express a rap lifestyle, but promotes a “team spirit” that harmonizes internal conflicts. It fosters friendship and provides emotional support to its members, preparing them for day-to-day challenges. Therefore, the feeling of belonging to the crew acts as a “virtual shelter” that helps them overcome the obstacles they face (Agier, 2001). Deko, a young Cape Verdean rapper, 21 years old, who has lived in Portugal since he was 6, unemployed at the time of the interview, better explains this issue to us:

Here it’s totally different, you don’t leave your job and go right home. Here there’s companionship, in every neighborhood there’s companionship, even if there are only two people, but there you have a group that stops and has companionship. (…) I can leave here and have whatever problem… I know if I go outside I can have “three fingers of conversation” with another member, have a conversation with him and tell someone what happened, tell him my problems or he’s telling them to me, this relaxes a person, you see, it leaves a guy cool.(…) Everyone wants to confess, we won’t confess at the church, we go down to the street. [Deko, 6 October 2005]

We can interpret the adoption of rap and membership in the Red Eyes Gang as part of a “culture of avoidance”. This encourages Arrentela’s youth of to reflect on their “place in the world” and, in a critical and unsubmissive manner, recast the definitions of their identities as poor, black and residents of a neighborhood with a bad reputation. They topple myths and negative representations in order to produce favorable identities of their social condition. It is a creative and maturative process that calls the dominant representations of race, class and nation into question and expresses a set of conflicting and dynamic experiences that are based on the youth culture of society’s less affluent sectors.

“Heart there and in body here in Pretugal.” In between mestizagem and affirmation of blackness

The creative way in which the youths of African descent of the Red Eyes Gang crew socialize among themselves is indicative of the profound differences in values and lifestyles that divide them from their parents. Their parents do not listen to rap music, rarely stay in the streets until dawn, dress without any distinctive connection to “hip hop culture” and do not speak slang or the kind of Creole adopted by their children. Such contrasts have a generational and ethnic character, and can only be understood if we consider that these young people, unlike their parents, did not follow a path of migration. Their cultural references are not governed by intergenerational overrides. Being socialized in an urban Portuguese context, their biographies, values and expectations are not rooted in a culture of origin, however much it exercises a strong influence in their lives. The decision of Jingal, a rapper, not to accompany his parents when they returned to Cape Verde after 15 years in Portugal, and to instead stay in Arrentela, explains this issue well.

I made my choice, I decided to stay because I am not fit for anywhere else, I’m used to this reality of buildings, highways and whatever else. The notion I had in my head is that if I went to Cape Verde I was going to die, I would be far from many things, and I’m a person who has to be as current as possible. (…) Because the reality there is totally different, here I have my buildings, I have my boys. [Jingal, 6 October 2005]

Jingal’s decision not only expresses the sense of belonging and loyalty to the group of friends from the Red Eyes Gang crew, but also the awareness that he would have to adapt to a different lifestyle than the one he was used to in Arrentela. As he adopts a standard of social and leisure time rooted in the social environment in which he lives, as all young descendants of Africans in Portugal do, the notion of “second-generation immigrants” doesn’t make any sense. That does not mean that this youth has no African influence. To the contrary, most of these youths have strong references in their parents’ countries of origin, especially in the areas of linguistics, feelings, music or food, creating significant emotional ties and representations that will influence them throughout their life, including in their own identity construction. However, this culture of origin is not sufficient to determine and understand their daily practices, nor how they build their ethnic references or a feeling of blackness.

The sharp contrast between histories, expectations and values of the Red Eyes Gang and their parents can be seen in the revolt and insubordination to their subaltern status and the racist situations they confront. Unlike their parents, who often have a passive and resigned attitude, who, since they are immigrants, have lower expectations, these youths are more likely to stand up against a structure of opportunity that discriminates against them. Many of the young blacks do not have Portuguese nationality, even though they were born in Portugal5, and those who have a Portuguese passport are not considered nationals by Portuguese society. This represents them as immigrants, given that the color white is an integral part of the imaginary about what it means to be Portuguese. Simultaneously, both the media and political institutions establish a direct relationship between crime and social housing estates and suburbs, whose protagonists are marked by the particularities of being young blacks and/or immigrants. This rhetoric racializes crime and the sense of threat in the figure of young blacks and immigrants, who are seen as potential criminals.

Carrying on the color of one’s skin an outward sign of one’s inescapable African descent, these young people feel the effects of segregation and stigmatization in Portugal. There was not one young man with whom I spoke in Arrentela who said they had not experienced situations of racial discrimination, an experience yet more common when one is poor and lives in a neighborhood with a bad reputation. Seeing people move away from them, or protecting their belongings with fear in their presence, being chased and beaten by police or security guards in shopping malls and in public because they are considered “suspect” and listening to the usual insults like “go back to where you came from!” were some of the more common stories. This backdrop makes racism one of the main themes addressed in the lyrics of Arrentela’s rappers, aside from the dissatisfaction of living in a country that relegates them to the “last step” on the opportunity structure.

Heart there and Body here in Pretugal / Mentally impppprisoned here in Pretugal / Without bread, but with poison and weapons for us to die in Pretugal/ Segregated so we are not anyone in Pretugal [Extract from the song “Pretugal” from Chullage’s album Rapensar: passado, presente e futuro]

This song demonstrates that we cannot visualize the complex processes of identity construction of young blacks of African descent without contextualizing the racism they face and the subordinate status they are forced to accept. It highlights the imagination of the Red Eyes Gang members in building tools and reflective statements about their lives. Rap is a great example for us to distinguish the particularities, continuities, and intergenerational changes in the way they reflect their status as blacks, poor and of African descent. The youth identify strongly with the history of rap and hip hop’s emergence, seeing similarities and continuities between their lifestyle and that of their American forerunners. And a lot of rap lyrics created, whether in Portugal or elsewhere in the world, produce new moral codes from the perspective of those who suffer racial and economic discrimination. Therefore, the rap lifestyle values blackness and the African cultural references of one’s relatives - elements constantly overlooked by the educational system and stigmatized by the media - giving new meaning to the experience of being a poor, black youth (Dayrell, 2005:122 ).

Reinventing their ethnic and cultural references

Essentialist theories about ethnic and cultural identities of Portugal’s black youth analyze them with a high proportion of homogenization, as if they were done and concluded from the beginning, ignoring the diversity of these youths’ biographical histories. However, as we approached the daily lives of these young people, we found that the predominant factor is the unstable and syncretic nature of their cultural manifestations.

Among the Red Eyes Gang, their cosmopolitan socialization and the intense intercultural diversity of their neighborhood makes it so that they are not concerned with maintaining an ethnic and cultural uniformity, as their references are focused on interaction with other populations and communities. There are not many divisions among those who have their origins in Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde and Angola, as all share very similar social and economic conditions and are part of the same story: “the African diaspora.” Even the Portuguese whites who tend to live in the neighborhood are well accepted in the crew, making national and ethnic distinctions unimportant factors in the internal dynamics of the group. This view is best explained by a neighborhood youth:

There is a lot of mixing, this nationality thing is going to shit, even the Portuguese, some Portguese are going to shit, you know. Sometimes you don’t even realize that the guy speaking Creole is Angolan. This is one of the most positive aspects, there is no division in this regard. (…) There are a lot of Angolans who can speak Creole, lots, and there are a lot of Portuguese who speak Creole. But beware! The Portuguese are very racist towards us, I’m talking about the young ones. And a lot of younger Portuguese that don’t live on this street, ok. Among those who live, but there aren’t a lot of Portuguese who live with us, there is no division on this point, among those who don’t live here is a strong division, there is distrust. [Chullage, August 30, 2005]

There young whites belonging to the Red Eyes Gang identify strongly with the children of Africans, since most of them grew up together and experienced the same feelings of economic deprivation, sharing a similar set of problems and difficulties. The influence of friends’ cultural references is demonstrated in the clothes of African origin they sometimes wear, Afro-influenced hairstyles, or the use of Creole6 to communicate with their peer group. Many of them use straps or cords made of round seeds (black with white balls) from Cape Verde. They serve as protection against the evil eye, and when they break, or the white part breaks, it means that someone is trying to do its owner harm. For young, black men, these accessories are suitable as symbols of belonging to a common origin (Africa); for young whites, they serve to affirm their admiration for African references. Regardless of the motivations that lead young people to use these “magic stones,” the importance of these accessories for the Red Eyes Gang serves to highlight the components of the hybrid style adopted by members of the crew, who nurture a deep respect for African traditions.

Guida, 23, is white, and one of the few girls who rap in Arrentela. Since she was a child, she has been influenced by her friends’ African cultural references, and it’s not hard to hear her speaking Creole in the streets of the neighborhood, as she confesses to prefer this language to Portuguese. The attraction to African cultural references is so strong that it has reached the point where she identifies more closely with Cape Verdeans than with the Portuguese themselves. The Portuguese are seen as unsupportive people, only caring about their appearance, while Africans would be much more generous.

I like Portuguese culture, on the other hand I like to have this in me, you know, and I like to be Portuguese and I admire my parents and some Portuguese families I know. But I am far more attracted to Africans, it attracts me more. How they see everything attracts me more, you know, how they live or what they do. The Portuguese are very… I usually say that the Portuguese are the cream of the rubble, you know, they have this obsession that they’re refined and are good shit, they’re junk, you know. They just have an obsession that they’re refined, so they despise others, they’re obsessed with disdain. (Guida, September 27, 2005)

The way the Red Eyes Gang appropriate Creole is an example of the dynamic reinvention of their parents’ cultural heritage. Besides giving it their own characteristics7, they withdrew it from the almost exclusive domain of the family, turning it into an urban language, of the street, and one that symbolizes belonging to a group of peers. It is the internal and daily language of the Red Eyes Gang, establishing itself as an instrument of transgression of the fundamental principles of the formal language of adults and school, besides serving as performative material to their cultural practices. It is no accident that many of them prefer to rap their lyrics in Creole, because they say this is the language which with they most identify.

The Red Eyes Gang members of African descent do not have a strong sense of belonging to Portugal, and those who claim to be Portuguese are in the minority. Many of them consider themselves Africans, others prefer to adopt the nationality of their parents as a form of self-identification (Cape Verdean, Angolan, Guinean, etc.) and there are those who see themselves in intermediate categories, such as African-Portuguese. Much more than the effective links with any African country, which in most cases are scarce, their resistance to considering themselves Portuguese is to be understood in the context of the experiences of segregation to which these young people were subjected. In this sense, racism, poverty and society’s rejection of considering them fully Portuguese - many of them do not have access to this nationality - are the decisive factors that cause many not to see themselves as nationals of this country.

Jingal never had the right to Portuguese nationality and, since his parents returned to Cape Verde, he cannot become legal in Portugal, a situation that prevents him from continuing his studies and entering the formal labor market. This limitation on the rights of citizenship eventually has negative consequences, not only in their daily lives, but in their own ways of representing themselves and Portuguese society.

To me I’m more Cape Verden, but it’s fucked up because I feel Cape Verdean, I speak Cape Verdean [Creole], but I don’t feel the smell of Cape Verde. I don’t feel the dust of Cape Verde, I feel the dust of Tuga [Portugal], they are different places. I feel more Cape Verdean, I can’t feel Portuguese because the Portuguese, as I say, do nothing for me. [Jingal, 6 October 2005]

The construction of identity is an eminently relational process, and cannot be thought of as a crystallizing, undynamic prism of an inherited culture. Although the individual lives identity as something stable and unified, it is characterized by being incomplete and constantly under construction (Hall, 2002). Among young people of African descent, identification with Portugal is heterogeneous and varies according to their class status, education level and series of life experiences, often contradictory, related to the experience of blackness and a given history in Portuguese society (Machado, 2006). For Deko, as for most young black people of African descent, his history is full of stigmatizing episodes, which cause him to be positioned to Portuguese society in a critical and detached way, since he is not considered Portuguese. Nothing prevents, in the near future, that this young man could change this position, something that will depend on the biographical path he takes.

The reproduction of ethnicization processes therefore depend, above all, on the persistence of the stigmatization and discrimination phenomena that were at their origin, and the actualization of anti-stigmatizing responses. (Pires, 2002:72)

Conclusion

In this paper, we proposed to call attention to the creative, mestizo way in which the Red Eyes Gang members of African descent affirm their blackness and reconstruct their ethnic and cultural references. The Red Eyes Gang only makes sense when it is thought of as a syncretic and working class youth culture, whose African and black references are valued and reinvented in an intercultural space. More than mere adjustments to their parents’ cultural heritage, their day-to-day life and lifestyle show a profound contrast between generations, a result of cosmopolitan socialization where various cultural references intersect. The strong adherence to rap and the creation of the Red Eyes Gang crew are significant examples of breaking with the sociocultural elements of their parents’ origins. Nevertheless, these practical and symbolic expressions also make use of cultural markers that reinforce a certain degree of continuity with their parents’ ethnic influences. This apparent contradiction “falls apart” when we come to see the cultural practices of these young people with a look “up close and inside,” framed in their daily lives (Magnani, 2003). A good example is rap, an urban musical style that is not based in the “roots” of their African parents. However, when they sing in Creole and construct positive identities for themselves by reformulating the meaning of being black and African in Portugal, this style questions the relationships of domination and subordination present in their day-to-day life, resituating them in a context of fighting for a place in the society in which they live. In this case, they affirm a black and African identity that, although not like their parents, promotes some of the inherited ethnic references. The same logic applies to the use of Creole on the streets of Arrentela (as in other neighborhoods on the outskirts of Lisbon), whose elements of continuity and change coexist harmoniously.

These examples demonstrate how creative young people reinterpret the cultural and ethnic heritage of their parents, establishing it as a strategic resource to be used for influencing the dominant definitions of ethnicity, race and nation, and better participate in discussions generated by the new contours of the society in which they live.

These examples demonstrate how creative young people reinterpret the cultural and ethnic heritage of their parents, establishing it as a strategic resource to be used for influencing the dominant definitions of ethnicity, race and nation, and better participate in discussions generated by the new contours of the society in which they live.

Bibliography

Abramovay, Miriam, Julio Jacobo Waiselfisz, Carla Coelho Andrade and Maria das Graças Rua, 1999, Gangues, galeras, chegados e rappers.Juventude, violência e cidadania nas cidades da periferia de Brasília, Rio de Janeiro, Garamond;

Agier, Michel, 2001, Distúrbios Identitários em Tempos de Globalização” in MANA–Estudos de Antropologia Social, 7(2):7-33;

Anderson, Benedict 1983, Imagined communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of nationalisms, London, Verso;

Dayrell, Juarez, 2005, A Música Entra em Cena. O rap e o funk na socialização da juventude Belo Horizonte, Editora UFMG;

Feixa, Carles, 1999, De Jóvenes, Bandas y Tribus, Barcelona, Ariel Publishing House;

Giroux, Henry, 1996, Fufitive Cultures: Race, violence & youth, London, Routledge;

Guiddens, Anthony 1995: Modernity and Identity del yo. El yo y la sociedad en la era contemporary, Barcelona, Ediciones Peninsula;

Hall, Stuart 2002 Cultural identity in post-modernity, Rio de Janeiro, DP & A Editora;

Machado, Luis Fernando, 2006, “Novos Portugueses? Parâmetros sociais da identidade nacional dos jovens descendentes de imigrantes africanos”, in Joana Miranda e Maria Isabel João (org.), Identidades Nacionais em Debate, Lisboa, Celta Editora, 19-46;

Magnani, José Guilherme Cantor, 2003, “De perto e de dentro: notas para uma Etnografia Urbana”, Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, 17(49):11-29;

Perista, Heloísa e Manuel Pimenta, 1993, “Emigração, Imigração em Portugal”, Actas do Colóquio Internacional sobre Emigração e Imigração em Portugal, Editora Fragmentos;

Pires, Rui Pena, 2002 “Mudanças na Imigração: uma análise das estatísticas sobre a população estrangeira em Portugal”, Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas, Lisboa, Celta Editora, nº39;

Raposo, Otávio Ribeiro, 2007, Representa Red Eyes Gang: das redes de amizade ao hip hop, Tese de Mestrado, Lisboa, ISCTE;

Research conducted as part of a master’s degree in Urban Anthropology at ISCTE - University Institute of Lisbon (Raposo, 2007).

1. This research was conducted as part of a master’s degree in Urban Anthropology at ISCTE - University Institute of Lisbon (Raposo, 2007).

2. The name Red Eyes Gang (Gangue dos Olhos Vermelhos) is a reference to the effect that smoking hash has on ones eyes, making them red.

3. The Chicago School problematized the notion of gangs in the 1920s, using it to designate an organization with instrumental rationality and the purpose of social mobility among its members. (Abramovay, 1999).

4. Called hip hop culture by its members, it is composed of four parts: rap, DJing (Disc-Jockey), break-dance and graffiti. The first two correspond to rap music, often produced from musical beats expertly drawn from other melodies by DJ’s. Rappers, also known as MC’s (Master of Ceremonies), use these beats to sing. Break-dance has established itself as the characteristic dance style of hip hop, in which the steps and choreography range from acrobatic to sporty and even to stylizing the movements of robots and martial arts. Graffiti, considered by its authors as “street art,” is the graphical aspect of hip hop, and express is expressed through drawings and written messages painted on walls and other public spaces of cities (including the cars of trains and metros ).

5. The current Portuguese law, amended in 1981, is based on jus sanguinis, unlike the previous law which was based on a balance between jus sanguinis and jus solis. This amendment aims to hinder access to citizenship by birth in nacional territory or by marriage to a native citizen. It is tied to the profound ideological changes in the way of representing the Portuguese nation, connected to the end of the colonial era.

6. Although not all of the crew’s young white members speak Creole, they all understand this language, given its centrality in everyday sociability experienced in Arrentela

7. The Creole spoken by these youths is full of slang, Portuguese expressions, words created in their own neighborhood or brought from other parts of the world (USA, Angola, Brazil, etc.), showing a strong mixture of different types of existing Creole: badio (spoken on the islands of eastern Cape Verde), sampadjudo (spoken on the islands of western Cape Verde (Santo Antao, Sao Vicente, Sao Nicolau, Sal and Boa Vista) and Guinea-Bissau.