How to Responsibly Collect the Work of Black Artists

Portrait of Destinee Ross-Sutton with, from left to right, works by David 'Mr. StarCity' White (showing the back of the work), Amoako Boafo, and Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe, from the exhibition 'Black Voices- Friend of My Mind.' Courtesy of Destinee Ross-Sutton.

Portrait of Destinee Ross-Sutton with, from left to right, works by David 'Mr. StarCity' White (showing the back of the work), Amoako Boafo, and Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe, from the exhibition 'Black Voices- Friend of My Mind.' Courtesy of Destinee Ross-Sutton.

Some say the appreciation of Black art is a trend, but Black art in itself is no more a trend than “white art.” It’s part of world culture, of art history, and history is being made every day. Black art should be appreciated for its contribution to humanity and history. Black people have always collected Black art, appreciated it, and cherished it, even when it received little recognition, as acknowledged in the new HBO documentary Black Art: In the Absence of Light. The light has started to shine more brightly on the rich contributions Black artists have made to the canon and culture as a whole. The musical genres that are quintessentially “American,” such as blues, jazz, and rap, were all created by African Americans. America has a dark history of building its riches on the backs of Black individuals—not only our physical labor, but our music, our fashion, and now our art. Loving culture and capitalizing on it at the expense of the people who created it is not new.

Murjoni Merriweather. Denicia, 2020. Ross-Sutton Gallery

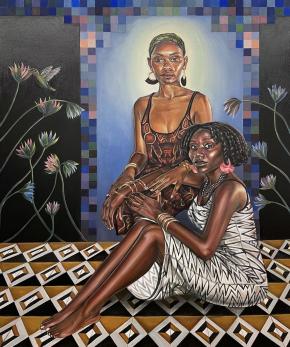

Murjoni Merriweather. Denicia, 2020. Ross-Sutton Gallery Sphephelo Mnguni. Umndeni, 2020. Ross-Sutton Gallery

Sphephelo Mnguni. Umndeni, 2020. Ross-Sutton Gallery

In the past few years, many deep-rooted ideas and systems have been exposed, and the art world has not remained untouched by these revelations. We are getting glimpses into the inner workings of the world’s institutions, and the people, structures, and social constructs that hold them up. That knowledge can bring an uncomfortable relief. We are now more adept at identifying what impedes progress and publicly challenging it or collectively calling for change. These “reveals” often lead to accountability—or they should. Understanding the impact one has on others and the environment is not always a given, but we are learning. This is how I try to operate. Empathy and discernment are good places from which to start. I’ve learned that humans’ inherent need to create art as a form of expression—the trait of exploring ourselves beyond the tangible world—is arguably what sets us apart in the animal kingdom.

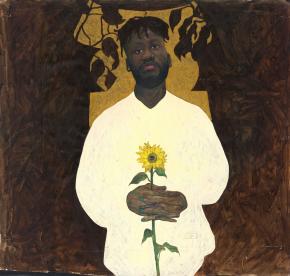

Raphael Adjetey Mayne. Selorm and his uncle, 2020. Ross-Sutton Gallery

Raphael Adjetey Mayne. Selorm and his uncle, 2020. Ross-Sutton Gallery

Unfortunately another distinctly human construct that separates us is greed. This is also an understanding with which I operate, and it has motivated me to help empower and connect with artists who have been subjected to this type of exploitation. Greed exists because we allow it. When I became a first-hand witness to what was happening to Amoako Boafo, as both a friend and an artist with whom I’ve worked closely for a number years, it made me cringe. His work first appeared at auction in February 2020. By the end of the year, an astounding number of his works had hit the auction block—33 pieces in all—one of the highest of any emerging artist in recent memory. Most works had been acquired directly from his studio, some from galleries. Could something be done to prevent this in the future? Could we at least make people aware of the consequences their choices might have for the artist and their career?

Amoako Boafo. Golden Stool (Self-Portrait), 2017. Ross-Sutton Gallery

Amoako Boafo. Golden Stool (Self-Portrait), 2017. Ross-Sutton Gallery Lanise Howard. Age of Aquarius , 2020. Ross-Sutton Gallery

Lanise Howard. Age of Aquarius , 2020. Ross-Sutton Gallery

It was an eye-opener. In addition to my curatorial work, I am an international art advisor acquiring art for clients. I began to review invoices I had received from different galleries I’ve worked with in the past. The majority of galleries, particularly the ones working with younger and emerging artists, have no terms or conditions listed on their invoices other than mandating prompt payment. I believe more should be expected from us.This was one of the many reasons that prompted me to add gallerist to my resume. To not only expand on the kind of exhibitions I wanted to see—the kind of exhibitions that highlight our rich contributions. Now I can provide platforms to underrepresented artists, emerging artists of color, and not only those who are already established. Being a gallerist also gives me agency, including the power to protect artists from the speculators.

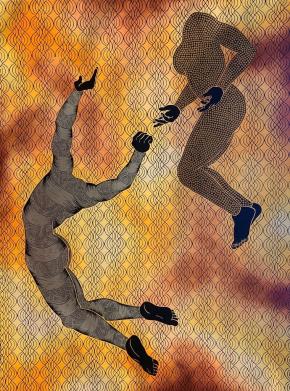

Olarinde Ayanfeoluwa. Hey, I can fly too, 2020. Ross-Sutton Gallery

Olarinde Ayanfeoluwa. Hey, I can fly too, 2020. Ross-Sutton Gallery Lanise Howard. Keepers of the door, 2020. Ross-Sutton Gallery

Lanise Howard. Keepers of the door, 2020. Ross-Sutton Gallery

My “Ross-Sutton Agreement” for the purchasing of art is nothing revolutionary; the terms are pretty straightforward. When a collector decides to sell a work, the artist has the right of first refusal when it comes to that sale. The agreement prohibits a buyer from selling the work at auction for three to five years after purchasing it. And I ask that the artist receive 15 percent from “the upside,” the profit from subsequent sales of their work.Today, an unprecedented number of Black artists in their twenties and thirties from all over the African diaspora are gaining global recognition. Historically speaking, now is an amazing opportunity to be able to participate in this rich cultural movement.

Educate yourself

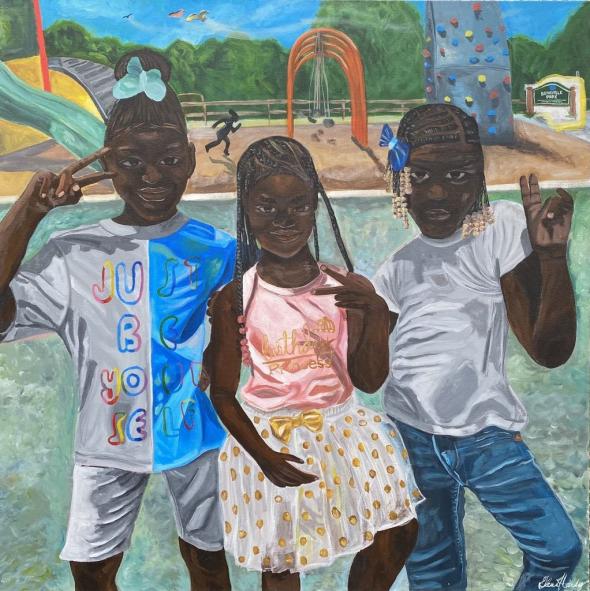

Glenn Hardy.They'll tell you that you won't be anything so to each other you must be everything (Sandbox), 2020. Ross-Sutton Gallery

Glenn Hardy.They'll tell you that you won't be anything so to each other you must be everything (Sandbox), 2020. Ross-Sutton Gallery

Our voices are now center stage; take the time to listen to them. Learn the history to understand and contextualize the narrative, the subject matter, the artist. This will also help you make more discerning choices, avoiding derivative work, for example. Let’s be honest: Not all art is great. Art is an investment in more than one sense. You and whomever you choose will get to see the work in your collection, and it can be enjoyed for years to come. And while there are many reasons why someone might eventually want to or even have to sell art from their collection, there are right and wrong ways of doing this.To be clear, I am not against collectors selling artworks from their collections. The art is your property, and you are allowed to do as you please. However, to ensure an efficient and equitable resale market for artists’ work, we as a community of buyers and sellers should observe certain practices. This also is in the best interest of you, the collector. If an artist’s market crashes, it’s not only to the detriment of them and their dealers. It also impacts the collectors who hold their work. Speculation is not good for the market.

Understand auctions’ impacts

Tiff Massey. Stunt 101 (Diptych), 2020. Ross-Sutton Gallery

Tiff Massey. Stunt 101 (Diptych), 2020. Ross-Sutton Gallery

A high result drives the market up or creates inconsistencies. A work not reaching its reserve price or low estimate, or failing to sell entirely, will slow down the artist’s market. Work showing up at auction too early in an artist’s career and going for a significantly higher price than primary-market works will likely tempt other collectors to sell in order to “cash in.” This can result in the market being flooded with a young artist’s work and its value can easily crash as a result. This is especially risky if the artist has yet to receive institutional support in the form of museum exhibitions and acquisitions, which is vital for the longevity of an artist’s career. Auctions are ideal for when an artist’s career is more established, not for newly created pieces or work still in the primary-market phase of the sales cycle.

Nurture the artists you support

If you want to invest in your investment—your collection—think about acquiring more than one work by the same artist, loaning a work for an exhibition, or even donating a piece to an institution. Support the artist by funding a show, catalogue, or research project. This will help their career, their market, and ultimately your investment in their art. Speak publicly about your relationship with their work. Support your local museums, join a museum acquisition fund, and support their efforts to diversify their collections. Support an artist residency program or an art school that has supported artists in your collection.

Resell responsibly

Sthenjwa Luthuli. 'Spirit Liberation' Ukukhululwa Komoya, 2020. Ross-Sutton Gallery

Sthenjwa Luthuli. 'Spirit Liberation' Ukukhululwa Komoya, 2020. Ross-Sutton Gallery Isshaq Ismail. Nonchalant I, 2020. Ross-Sutton Gallery

Isshaq Ismail. Nonchalant I, 2020. Ross-Sutton Gallery

Involve the artist or their representatives and figure out ways to reintroduce the work to the market that won’t hurt the artist. New work by a young or emerging artist showing up at auction can destabilize their long-term market, even more so if the number of works being sold increases.If you want or need to sell within three to five years of acquiring the work, give the artist and then their representatives the right of first refusal. Give them the same terms you would anyone else. If they don’t elect to acquire the artwork, sell it privately. The artist’s dealers may even be able to place it for you.Make sure that whomever you entrust to sell the work is both capable, honest, and discreet. Be discerning! Have proper contracts in place so they won’t just blast it all over the market trying to make a profit from the sale. Someone might tell you they have a buyer when in actuality they don’t, and then they will desperately try to find a buyer. Even a rep in an auction house’s private sales department might share the work with one too many potential buyers; before you know it, everyone in the business knows the work is being offered for sale, and you might end up having to sell it at a discount.

Share the profits

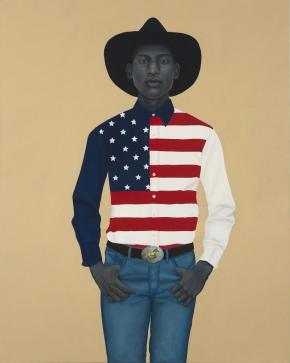

Amy Sherald. All the unforgotten bliss (The early bird), 2017. Hauser & Wirth

Amy Sherald. All the unforgotten bliss (The early bird), 2017. Hauser & Wirth Amy Sherald. What's precious inside of him does not care to be known by the mind in ways that diminish its … Hauser & Wirth

Amy Sherald. What's precious inside of him does not care to be known by the mind in ways that diminish its … Hauser & Wirth

I recently asked the artist Amy Sherald what advice she’d give to collectors. She was very clear: “Don’t buy with the intention of reselling and, if you do, think about sharing the return on that investment with the artist.”Many countries have resale royalty laws on the books, which mandate paying a percentage to the artist when works are resold within their lifetime and 70 years thereafter. In the U.S., musicians, songwriters, authors, and their beneficiaries receive such royalties from their work. While visual artists don’t have the same legal protections, that shouldn’t mean collectors, galleries, and institutions don’t have a moral duty to them. Why not share a small percentage of any profit from the sale of their work with the artist or their estate?

Be more than a collector

A true collector understands that they are a steward. They acquire the art for the art’s sake, not just to profit financially. A steward is a proud caretaker who educates themselves and others, taking a vested interest in the artist and their practice, history, culture, world view, and expression. Understanding one’s desired role in the art world is a requirement to be a responsible collector of any art, whether created by a Black artist or not. Becoming a steward involves commitment and perseverance. Moving from invested observer to active supporter takes more than money. It takes integrity.

Article originally published by Artsy at 17.02.2021