In the Streets with Antifa

Antifascists allege that the Portland Police Bureau has long tolerated crimes by far-right groups while cracking down on leftist demonstrators. Arrests by the bureau’s rapid-response team can look vindictive and gratuitously violent.

Photograph by Philip Montgomery for The New Yorker

Photograph by Philip Montgomery for The New Yorker

Trump is vowing to designate the movement as a terrorist organization. But its supporters believe that they are protecting their communities—and that confronting fascists with violence can be justified.

Shortly after noon on September 26th, about fifteen hundred antifascists gathered on the lawn of Peninsula Park, in Portland, Oregon. Some wore black bloc—the monochromatic clothing that renders militant activists anonymous to law enforcement—but the event was family-friendly, and most attendees had dressed accordingly. Booths set up in a leafy grove offered herbal teas and tinctures, arts and crafts, condoms and morning-after pills, radical zines, organic vegetables. Above a stage, a banner read “everyday antifascist / come for the anarchy / stay for the soup.” In July, President Donald Trump had claimed, without evidence, that anarchists were throwing soup cans at police during demonstrations for racial justice. When the anarchists were arrested, he explained, “they say, ‘No, this is soup for my family.’ ” Inevitably, “soup for my family” became a tongue-in-cheek slogan at Portland protests.

Other Presidential statements have been harder to make light of. Throughout the nationwide upheaval set in motion by the police killing of George Floyd, in Minneapolis, on May 25th, Trump has vilified demonstrators as nefarious insurrectionists. Much as adversaries of the civil-rights movement once contended that it had been infiltrated by Communists, he invokes antifascists, or Antifa, to delegitimatize Black Lives Matter. A week after Floyd’s death, as popular uprisings spread from Minneapolis to other cities, the President declared, “Our nation has been gripped by professional anarchists, violent mobs, arsonists, looters, criminals, rioters, Antifa, and others.” As the election nears, he has portrayed Antifa as a grave security threat that the Democrats and their Presidential nominee, Joe Biden, will let destroy the country. During the first debate, after Biden noted that Trump’s F.B.I. director, Chris Wray, had described Antifa as “more of an ideology or a movement than an organization,” Trump scoffed, “You gotta be kidding me.” He told Biden, “They’ll overthrow you in two seconds.”

Such dire warnings are wildly disconnected from reality. Most Americans who identify as antifascists don’t belong to any particular group, and there is no national Antifa hierarchy or leadership. To date, one American has been killed by someone professing an antifascist agenda; right-wing extremists, by comparison, have been responsible for more than three hundred and twenty deaths in the past quarter century. The only known plot to “overthrow” the government in recent months was hatched by right-wing militia members, who, according to the F.B.I., planned to kidnap Michigan’s Democratic governor, Gretchen Whitmer. In June, I stood next to the alleged ringleader, Adam Fox, during a rally at Michigan’s capitol, while a speaker yelled, “We are here demanding peace as these terrorist organizations want to burn down our cities!” Fox carried an assault rifle and wore an ammo vest with a patch that said, “Si vis pacem, para bellum”: “If you want peace, prepare for war.”

It is true that, in response to such right-wing events, some leftists have mobilized under the name Antifa, following a tradition with specific principles, among them a willingness to engage in violence. The first speaker at Peninsula Park, a Black activist and hip-hop artist named Mic Crenshaw, was one of the progenitors of this tradition. At fifty years old, he had at least a couple of decades on most people in the crowd. Wearing sunglasses, a backward baseball cap, and a bulletproof vest over a plaid flannel shirt, Crenshaw said, “I used to tell people our motto was ‘We go where they go.’ And there’s a lot of courageous people out here doing the same thing today.” He patted his flak jacket. “I never thought, thirty years ago, I’d be standing up here with one of these things on.”

Crenshaw grew up in Minneapolis, where, as a teen-ager, he became fascinated by the city’s nascent hardcore-punk scene. “I would ride through uptown and see the kids with their cool haircuts and studded jackets,” he recalled when I visited him at his home, in Portland, a few weeks before the Peninsula Park event. In 1986, as a high-school junior, Crenshaw joined with six peers—five of them white and one Native American—to start a skinhead crew called the Baldies. They shaved their heads, found flight jackets at an Army-surplus store, and ordered Doc Martens from catalogues. The British skinheads whom the Baldies emulated were influenced by Jamaican-immigrant culture, and believed in multiethnic solidarity. “We were trying to become the Minneapolis version,” Crenshaw said.

But punk music also appealed to neo-Nazis. Soon after the Baldies formed, a gang called the White Knights began harassing people of color in Minneapolis. Crenshaw threw a piece of concrete through the window of a White Knight leader’s house. “That was the jump-off,” he told me. The act precipitated a “protracted period of street violence”: weekly brawls with bats, chains, pipes, knives, brass knuckles, and pepper spray. “Luckily, no one died,” Crenshaw said. “People were definitely going to the hospital, though.”

The Baldies made pacts with militant leftists and gravitated toward anarchist tenets of mutual aid and community defense. Crenshaw was drawn to Communism. He said of the Baldies, “Our politics emerged from our survival-based organizing.” Another former Baldie told me, “Although many of us were interested in reading theory, what was driving our action wasn’t adherence to a particular ideology—it was meeting the threat as it needed to be met. It was very practical.” For Crenshaw, it was existential: “As a Black kid, I was fighting against people who wanted to kill me.”

One hub for young radicals in Minneapolis was Backroom Anarchist Books, which sold revolutionary European newspapers like Class War. From these periodicals, the Baldies learned about Anti-Fascist Action, a British organization dedicated to physically confronting racists and anti-Semites. Anti-Fascist Action had revived a legacy in England stretching back to the thirties, when Londoners prevented Oswald Mosley and his British Union of Fascists from publicly assembling. The Baldies effectively chased the White Knights out of Minneapolis, and then resolved to expand their crusade against white supremacy beyond the skinhead subculture. In 1987, they established Anti-Racist Action, or A.R.A., and began recruiting skaters, college students, and Black and Latino gang members. Explaining A.R.A.’s decision to tweak the British name, Crenshaw told me, “To us, the word ‘fascist’ sounded too academic. But everybody knew what a racist was.”

After high school, Crenshaw and his friends followed punk tours around the country, setting up A.R.A. chapters. In 1991, the group convened its first national conference, in Portland. The city had been a center of white-supremacist organizing since the seventies, when Posse Comitatus—a virulently racist and anti-Semitic paramilitary movement—was launched there. The Aryan Nations, a hate group in neighboring Idaho, sponsored neo-Nazis in Oregon who talked of turning the region into an all-white ethno-state. Before the A.R.A. conference, an Ethiopian immigrant in Portland was beaten to death by three acolytes of a group called White Aryan Resistance, or war. “Portland was in the national spotlight as a hotbed of racism,” Crenshaw said. “We wanted to let our presence be felt, and say, ‘We’re not gonna stand for that.’ ”

war and the Aryan Nations were eventually crippled by civil lawsuits, and, as other avowed white-supremacist outfits also receded, A.R.A. membership dwindled. When Crenshaw moved to Portland, a year after the conference, he stepped away as well, focussing instead on music and teaching. Both A.R.A. and the Baldies consisted largely of white people fighting white racism in white spaces, and, he told me, “I couldn’t do that anymore.”

In 2007, neo-Nazis attempting to reinvigorate the vestiges of war planned to hold a white-power music festival near Portland. Former A.R.A. members helped local residents pressure the host venue to pull out. Half a dozen of these activists, sensing a need for renewed vigilance, created Rose City Antifa—the first official antifascist organization in America. For Crenshaw, the evolution of A.R.A. into Rose City Antifa, combined with Portland’s centrality in the national protest movement that began in Minneapolis this May, shows that “the two cities are linked in a continuum of antifascist consciousness.”

In mid-September, I met with two current members of Rose City Antifa, Sophie and Morgan, in another Portland park. (Asking for anonymity, they used pseudonyms.) Sophie, who is transgender, explained that “some of the A.R.A. groups were pretty strongly in a world of toxic masculinity,” but Rose City Antifa has always had “a strong feminist and queer component.” A number of its founders were women. Morgan, who identifies as a butch lesbian, said that Rose City Antifa adopted a more nuanced approach: “A.R.A. was street-level confrontation with white-supremacist gangs. We wanted to broaden the scope to encompass more activities that we saw as fascist threats.”

Such threats proliferated during the next eight years. The election of President Barack Obama galvanized the so-called Patriot Movement, composed of hundreds of far-right groups and armed militias hostile to Muslims, immigrants, and the L.G.B.T.Q. community. Though the Patriot Movement was seldom explicitly racist or anti-Semitic, it depicted the federal government as corrupted by un-American forces inimical to white Christians—a resurrection of the Posse Comitatus world view. Despite this troubling ferment, antifascism remained a backwater of leftist activism throughout the Obama Administration, as progressives focussed on the rise of the Patriot Movement’s political analogue: the Tea Party.

Then came Donald Trump, buoyed by a wave of white nationalism calling itself the alt-right. In 2017, many Americans were stunned when throngs of white supremacists carried torches and Nazi flags through Charlottesville, Virginia, chanting “Blood and soil!” and “Jews will not replace us!” Antifascists, however, were prepared. Hundreds of them travelled to Charlottesville, in fidelity to the “We go where they go” credo. Clashes culminated in a neo-Nazi plowing his car through a crowd of counter-protesters, killing a woman. The former K.K.K. Grand Wizard David Duke told a reporter, “We are determined to take our country back. We’re going to fulfill the promises of Donald Trump.” Later, Trump said that there had been “very fine people on both sides” in Charlottesville. Duke praised his “honesty” and “courage.”

At Peninsula Park, Mic Crenshaw told his audience that “across-the-board collusion” between the U.S. government and white supremacists was nothing new. In the past, however, “they used to try to lie and cover shit up.” Under Trump, the alliance was on display with “unprecedented transparency.” Now, Crenshaw said, “the question is, How are we going to protect ourselves?”

In 2016, Rose City Antifa joined the Torch Antifa Network, which included former A.R.A. chapters from Illinois, California, and Texas. There are now ten Torch affiliates, which share a commitment to disrupting far-right organizing. According to Rose City Antifa, although affiliates occasionally exchange information and advice, there is little practical collaboration.

The network focusses much of its energy on Internet activism: doing research online, identifying proponents of bigotry, and then publicly exposing—or “doxing”—them. Rose City Antifa spent part of its early years doxing people involved with Volksfront, an international racist gang headquartered in Portland. Whereas A.R.A. would have hunted Volksfront members in the streets, Rose City Antifa publicized their activities to employers, neighbors, and relatives. In 2012, Volksfront’s U.S. chapters disbanded.

Rose City Antifa doesn’t disclose how many members it has, but Sophie estimated that doxing investigations take up about a hundred hours per week. Reports on individuals, Sophie said, must meet rigorous standards: “We do what we can to make it an undeniable fact that the people we are doxing are tied explicitly to violent rhetoric or acts of violence. As muddied as the lines are right now, we don’t want to go after someone for wearing a maga hat.”

Whenever people deemed worthy of doxing hold gatherings in public spaces, antifascists undertake to shut them down. “Research and action go hand in hand,” Morgan said. In “Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook” (2017), the scholar and activist Mark Bray writes that, after the Second World War, Jewish veterans created the 43 Group, which stormed fascist assemblies with the aim of knocking over the speakers’ platform. Though conservatives and liberals alike now criticize “no-platforming” as a violation of free speech, antifascists take the 43 Group’s view that incipient fascism tends to metastasize if left unchecked; given that fascist movements ultimately aspire to mass oppression, or even genocide, they must be stifled early.

In the U.S., no-platforming campaigns have roiled college campuses. Three years ago, when the right-wing polemicist and Breitbart editor Milo Yiannopoulos was invited to address Republican students at the University of California, Berkeley, antifascists besieged the venue, breaking windows and lighting fires. The speech was cancelled. Shane Burley, a Portland native and the author of “Fascism Today: What It Is and How to End It” (2017), told me that many Americans recoil from such modern incarnations of no-platforming because “it has been extended to people who aren’t consensus Nazis—people who not everybody agrees deserve to be hit.” But Burley argues that antifascists are hardly to blame for this: “It’s the Trump effect. Nazi rallies have merged with the Republican base, and now they’re in the same space together.”

The activist and hip-hop artist Mic Crenshaw co-founded Anti-Racist Action, a precursor to Antifa, in Minneapolis in 1987. Photograph by Philip Montgomery for The New Yorker

The activist and hip-hop artist Mic Crenshaw co-founded Anti-Racist Action, a precursor to Antifa, in Minneapolis in 1987. Photograph by Philip Montgomery for The New Yorker

Such merging is particularly common, Burley and other antifascists say, in the Pacific Northwest. During the lead-up to the 2016 election, Joey Gibson, a thirty-six-year-old house-flipper in Vancouver, Washington, founded the Christian pro-Trump movement Patriot Prayer. A former high-school football coach, Gibson has an athletic build often accentuated by T-shirts that display his many tattoos, including one of a Spartan helmet and the words “warriors for freedom.” In a recent phone interview, he told me that he started Patriot Prayer because he felt that his political values had become taboo. He wanted to venture into “the hardest cities to voice your opinion in as a conservative”: places like Berkeley, San Francisco, and—just across the Columbia River from Vancouver—Portland. Gibson carefully avoids endorsing violence or espousing racism; his mother is Japanese, and Patriot Prayer has attracted some people of color. But it has also attracted white supremacists and members of known hate groups. According to Rose City Antifa, which has identified dozens of these individuals at Patriot Prayer events, and published evidence of their allegiances online—from screenshots of racist Facebook screeds to photographs of swastika patches—Gibson offers neo-Nazis cover and provides them with a fertile recruiting ground. Another member of Rose City Antifa, who goes by Ace, said, “The umbrella is broad enough to encompass a huge portion of the reactionary radical right, up to and including neo-Nazis, and that’s why these rallies become such incredible spaces for radicalization.” (Gibson has stressed that Patriot Prayer is a movement without members, and denies that it condones violence or white supremacy.)

Around the time that Gibson launched Patriot Prayer, Gavin McInnes, a co-founder of Vice Media, created the Proud Boys, in New York. McInnes has called the Proud Boys a “gang” of “Western chauvinists”; the F.B.I. classifies it as an “extremist group with ties to white nationalism.” A former Proud Boy organized the neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville—and called the woman who was killed there “a fat, disgusting Communist.” The Proud Boys have been banned from Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, but their account on Parler—a social network catering to conservatives—has nearly seventy thousand followers. Unlike Gibson, McInnes has openly celebrated violence against the left. In 2016, when a handful of Patriot Prayer supporters formed a Vancouver chapter of the Proud Boys, they became the muscle at Gibson’s events.

During a Patriot Prayer rally held in Portland in April, 2017—billed by Gibson as the March for Free Speech—a thirty-five-year-old man named Jeremy Christian was filmed barking racial slurs and wielding a bat. (He was subsequently ejected from the march.) Four weeks later, Christian boarded a train in Portland and accosted two Black teen-age girls, one of whom was Muslim and wore a hijab. When three men intervened, Christian fatally stabbed two of them. He was later arrested, and at his arraignment he screamed, “Get out if you don’t like free speech!,” and “You call it terrorism, I call it patriotism!” The murders took place amid a historic national surge in anti-Muslim hate crimes, which Trump’s critics linked to his pattern of Islamophobic rhetoric (such as when he called for “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States”). Nine days after the killings, Gibson led a Trump Free Speech Rally in Portland, which was heavily attended by Patriot Movement militias. Although Gibson disavowed Christian and presided over a moment of silence for his victims, he then introduced a speaker who recounted—to raucous applause—having recently “cracked the skulls of some Commies.”

Patriot Prayer and the Proud Boys began regularly descending on Portland, where altercations with Rose City Antifa counter-protesters were virtually guaranteed. Chaotic fistfights became recurrent events downtown. The purported reasons for Gibson’s rallies varied—“Him Too,” “Gibson for Senate”—but Morgan, the Rose City Antifa member, said, “What they’re really coming for is a fight. They’re coming with weapons, hyped up and ready to throw down with whoever confronts them.”

Antifascist doctrine does not allow for avoiding such confrontations: “They will not pass” is another precept, deriving from the Spanish Civil War. But, in the summer of 2018, several activists in Portland created a new organization—PopMob, short for Popular Mobilization—which aimed to enlist a more diverse, and less militant, league of protesters to counter Patriot Prayer and the Proud Boys. Whereas Rose City Antifa has strict vetting protocols for new members, Effie Baum, a co-founder of PopMob, told me, “Everybody is welcome under our tent, except cops and fascists.” PopMob promotes what Baum calls “everyday antifascism,” not as an alternative but as a complement to front-line combatants in black bloc. “If you’re gonna punch a Nazi, punch a Nazi,” Baum said. “If you’re gonna stand in the back with a sign that says ‘Love Trumps Hate,’ there’s room for both of us.”

The feud reached a head this summer, on August 29th, when hundreds of Trump supporters met in the parking lot of a suburban shopping mall, then drove into Portland together. The route was announced just before the caravan’s departure, to stymie protesters. That afternoon, I interviewed Shane Burley at a bar on the east side of town; after leaving the bar, I pulled onto a road full of honking cars and trucks bedecked with huge American flags and “Trump 2020” banners. I followed the caravan out of the city, not realizing that dozens of drivers had broken off and headed downtown, where local residents shouted obscenities at them and threw water bottles. Some of the Trump supporters fired paintball guns and pepper spray from their vehicles; others got out and assaulted protesters.

It was dark when I arrived downtown. As I parked on a wide avenue in the shopping district, several people in black bloc sprinted by. Turning a corner, I came upon a small crowd facing a police cordon. Behind the officers, a dead body lay in a pool of light.

The victim was Aaron Danielson, a thirty-nine-year-old supporter of Patriot Prayer. He’d been shot by Michael Reinoehl, a forty-eight-year-old white man who—though unaffiliated with Rose City Antifa or PopMob—once wrote on Instagram, “I am 100% ANTIFA all the way!” Reinoehl later claimed that he had fired in self-defense, and a cannister of bear spray and a telescopic truncheon were found on Danielson. At the time, however, nobody in the crowd knew what had happened or who was involved.

“What are you doing here?” I heard someone say. A man in black bloc, his face concealed behind a balaclava and ski goggles, was addressing a man with a trimmed beard, wraparound sunglasses, and a baseball hat emblazoned with the name Loren Culp—the Republican gubernatorial candidate for Washington. He also wore a hooded sweatshirt that said “Patriot Prayer.”

“It’s Joey Gibson!” someone said.

Gibson later told me that he and Danielson had driven into Portland in the same truck. After following the pro-Trump caravan back to the shopping mall, they received messages about the skirmishes downtown, and, separately, they returned to the city. Gibson had happened on the crime scene accidentally, and he had no idea that the corpse thirty feet away was Danielson’s.

Another man in black bloc told Gibson that he’d heard the victim had been murdered by a Proud Boy. This seemed to be the crowd’s prevailing assumption, though neither Antifa nor the Proud Boys had killed anybody before. Affecting a casual posture, Gibson waved dismissively and said, “That’s what they always be yelling and screaming about—‘Some white supremacist killed someone tonight.’ They say that shit all the time.”

“Because you bring white supremacists to town all the time,” someone said.

“I’m brown,” Gibson responded. He rolled up his sleeve and showed his skin tone.

People pressed around Gibson, shouting at him to leave. When he asked, “Why don’t you guys stop acting like Nazis?,” a man in a Young Turks sweatshirt spit in his face.

“Can we stop with the hate?” Gibson said, making no move to wipe off the saliva.

Protesters continued to arrive, and, as the volume and ferocity of their insults escalated, Gibson turned to a blond woman who’d been standing at his side and said, “Let’s go.” A mob of at least fifty young people pursued them. Gibson kept up a show of equanimity until his hat and glasses were snatched away. Soon, drinks were emptied on him, objects were hurled at him, eggs were smashed on him, and he was punched and pepper-sprayed. With the blond woman’s help, he stumbled forward while someone rang a cowbell in his ears and others strobed flashlights in his eyes.

“Kill the Nazi!” someone screamed.

The mob grew. As far as I could tell, all of Gibson’s assailants were white. At some point, several people pushed their way to Gibson and escorted him down the street, keeping at bay the most belligerent aggressors. A short Asian man in a bicycle helmet yelled, “Let him leave, goddammit! Everyone back the fuck off!”

After several blocks, Gibson and the woman ducked into a gas station, and an employee locked the door behind them. The man in the bicycle helmet blocked the entrance, but people smashed the windows and kicked open a side door. Another protester raised his gas mask and pleaded, “He’s a fucking Nazi, but are you going to lynch him?”

The police arrived, and the protesters fled. Gibson vomited in the bathroom, washed the pepper spray from his eyes, and called a friend to pick him up. A reporter looking to identify the shooting victim texted Gibson a photograph of medics treating Danielson. “I recognized him right away,” he said.

After the crowd dispersed, I found the man in the bicycle helmet at a nearby 7-Eleven. His name was Rico De Vera, and he was a twenty-seven-year-old Filipino-American who studied engineering at Portland Community College. Earlier that day, a Trump supporter had shot him in the face with a paintball gun; the flesh around his left eye was stained neon pink. De Vera had been regularly participating in Black Lives Matter protests since May. Although he remained enthusiastic about the movement, he worried that in Portland it had been subsumed by the city’s militant antifascist culture, which he saw as violent and white. “It pisses me off,” he said. “People are going to use tonight to say that Black Lives Matter is a bunch of thugs.”

We walked a few blocks to a park outside the Multnomah County Justice Center, where people had congregated by a perimeter of concrete barriers and metal fencing. This was where most of the Patriot Prayer rallies and Antifa counter-protests had taken place; more recently, it had become a locus for Black Lives Matter demonstrations. In June, huge crowds had lobbed fireworks, bottles, and other projectiles at the Justice Center, a fortresslike monolith that contains the Portland police headquarters and the county jail. On June 26th, Trump called for the deployment of federal agents to protect government property throughout the country from “left-wing extremists.” The Justice Center stands beside a U.S. District courthouse, and in July more than a hundred employees of the Department of Homeland Security and the U.S. Marshals Service arrived in Portland, ostensibly to protect the federal building. A U.S. marshal shot a twenty-six-year-old protester in the head with an impact munition, fracturing his skull; the protester had merely been holding up a boom box with both hands. Such excessive force drew larger and larger crowds to the courthouse until Chad Wolf, the acting Secretary of Homeland Security, began to relinquish responsibility to the Oregon State Police, in late July.

Now a young woman with a megaphone told the people at the Justice Center that she had an announcement. “I just got word that the person who died was a Patriot Prayer person,” she said. “He was a fucking Nazi. Our community held its own and took out the trash. . . . I am not sad that a fucking fascist died tonight.”

Everyone cheered.

Although years of antifascist activism in Portland have likely contributed to the extraordinary staying power of its Black Lives Matter movement, white antifascists insist that they’ve played no role in organizing racial-justice protests. Sophie, of Rose City Antifa, said, “We don’t feel like, as a group, we should be taking away space from people who have dedicated their lives to this.” However, Sophie added, “we are fully supportive, and many of us attend as individuals.” Effie Baum, the PopMob co-founder, similarly told me, “We’ve been really intentional about not taking the lead on stuff that’s been happening since George Floyd was murdered.” One reason for this, Baum explained, was that “we’re a mostly white organization.”

Rico De Vera, a participant in Black Lives Matter protests in Portland, worries that the movement has been subsumed by the city’s militant antifascist culture. After one chaotic protest, he said, “It pisses me off. People are going to use tonight to say that Black Lives Matter is a bunch of thugs.” Photograph by Philip Montgomery for The New Yorker

Rico De Vera, a participant in Black Lives Matter protests in Portland, worries that the movement has been subsumed by the city’s militant antifascist culture. After one chaotic protest, he said, “It pisses me off. People are going to use tonight to say that Black Lives Matter is a bunch of thugs.” Photograph by Philip Montgomery for The New Yorker

Portland, whose population is six per cent Black, is the whitest big city in America. The historian Walidah Imarisha traces the origin of these demographics to the founding of Oregon, which settlers envisaged as a “white utopia.” When Oregon joined the union, in 1859, it became the only state with an outright ban on Black people. Later, redlining policies and urban-renewal projects displaced many African-Americans, a process reprised by more recent waves of gentrification.

The Black Lives Matter demonstrations in Portland are resolutely non-hierarchical; as a rule, however, white protesters defer to their Black and brown peers, who are usually the only people to use megaphones, deliver speeches, and lead marches. Since the federal withdrawal from the Justice Center, the protests have targeted the Portland police with nightly “direct actions.” Every day, a message circulates on social media announcing a rendezvous point (usually a park); from there, protesters depart to a nearby destination (usually a precinct house). A diffuse, anonymous network, communicating on encrypted messaging apps, chooses these locations. Although Fox News and the Trump Administration characterize Portland as an apocalyptic war zone, some direct actions attract fewer than a hundred people, and even on well-attended nights their impact is undetectable beyond a few square blocks.

Still, property destruction does occur, and, because the vast majority of protesters are white, this has been a source of tension with some residents of color. In June, after rioting damaged several businesses along Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, in a traditionally African-American neighborhood in North Portland, a consortium of Black community leaders held a press conference to condemn the vandalism. J. W. Matt Hennessee, the pastor of Vancouver Avenue First Baptist Church, told white protesters, “Get your knee off our neck. That is what you are doing when you do stuff like this.” Ron Herndon, who led civil-rights campaigns in Portland during the eighties, called the vandals “demented” and said, “Go back to whatever hole you came from. You are not helping us.” On the weekend of Columbus Day, which Portland recognizes as Indigenous Peoples Day, protesters toppled a statue of Abraham Lincoln, shot through the windows of a restaurant owned by a Black veteran, and broke into the Oregon Historical Society, where they inexplicably stole a celebrated quilt commemorating African-American heritage, stitched by fifteen Black women in the nineteen-seventies. (Police found the quilt lying in the rain a few blocks away, slightly damaged.) The leaders of thirty Native American groups released a statement comparing the conduct to “the brutish ways of our colonizers.”

Two days after Aaron Danielson was killed, I joined a few hundred protesters outside a luxury building where Ted Wheeler, Portland’s Democratic mayor, owns an apartment. In Portland, the mayor serves as the commissioner of the police bureau, which protesters are determined to see defunded. As a picnic table from a restaurant was dragged into the street and set on fire, I spotted Najee Gow, a twenty-three-year-old Black nurse, leading chants of “Fuck Ted Wheeler!” I’d met Gow the previous week, when several young women had staged a sit-in in Wheeler’s lobby. Gow, who wore a peacoat over a red-white-and-blue tank top, had been incensed that no African-Americans were included in the demonstration. “It’s what they’ve always done,” he’d said. “Hijack Black people’s movements. This is disgusting.”

As I spoke with Gow near the burning table, we were interrupted by shattering glass. A young white man in black bloc was swinging a baseball bat into the window of a dentist’s office on the ground floor of Wheeler’s building. “That makes me want to beat them up,” Gow said. Like Rico De Vera, he felt that such behavior benefitted only those who wanted to malign Black Lives Matter, and he also worried that it bred general animosity toward Black people: “They’re putting Black lives at risk. African-Americans are constantly out here telling them to stop, but they won’t. So, at the end of the day, it’s, like, ‘Are you racist?’ ”

A white man with a hammer joined the guy with the bat, and together they breached the office. People entered. A loud explosion echoed from inside, followed by smoke and flames. Gow went over to challenge them. While they argued, a blond woman in a hoodie ran up and spray-painted an arrow on the wall, pointing to the broken window. She then scrawled, “This is the language of the unheard.”

In “Fascism Today,” Shane Burley writes that antifascism is often practiced “as part of a larger revolutionary struggle.” Many of the white protesters in Portland subscribe to a radical political agenda. At one direct action, I met half a dozen antifascists in their early twenties who called themselves the Comrade Collective. They all had on black bloc, and several carried small rubber pigs that squealed when squeezed. Each had adopted a nickname. Firefly, a self-described Marxist-Leninist, told me, “It’s more than just Black Lives Matter. We believe that racism is built into capitalism, and we want to destroy the system of oppression.”

Spinch, whose mouth was covered with a blue bandanna, said, “It often gets boiled down to ‘Capitalism is the problem.’ Which, like, yes. But also colonialism.” Spinch had been protesting since May, and the experience had been formative: “I’m objectively very young, and haven’t been an autonomous adult for very long, so this is my first real foray into dedicated activism. I got tear-gassed my first night out here. If that doesn’t radicalize you, I don’t know what will.”

A comrade named Brat added that the pandemic had revealed the alarming depth of the government’s ineptitude. “Before COVID, I was trying to get more involved in local politics,” Brat said. “Now I sort of feel like that’s a dead end.”

“I was gonna run for City Council!” Spinch said. “But there’s no point. The system is fucked.”

I asked what the alternative was.

“Anarchism.”

“And one simple way to get us closer to that is defunding the police,” Brat said.

The animating conviction that America’s economic, governmental, and judicial institutions are irremediable distinguishes Portland protesters from others around the country. Many of them view inequality not as a failure of the system but as the status quo that the system was designed to preserve; accordingly, the only solution is to dismantle it entirely and build something new.

In Minneapolis, marchers chanted, “No justice, no peace!” In Portland, they cry, “No cops! No prisons! Total abolition!” Occasionally you hear “Death to America!” The night after Ruth Bader Ginsburg died, I accompanied a march to the Gus J. Solomon U.S. Courthouse, where protesters smashed the glass doors and cut down a flag that had been lowered to half-mast. The flag was brought to the police headquarters, doused with hand sanitizer, and set ablaze. On a boarded-up window, a white man in black bloc spray-painted, “the only war is class war.”

Popular chants at the protests include “A.C.A.B.—All Cops Are Bastards!” and “No good cops in a racist system!” (The A.C.A.B. acronym was popularized by British punks in the eighties; when the Baldies emerged, in Minneapolis, they used it as a code word.) Polls indicate that a large majority of Americans of all races oppose abolishing police departments, and the absolutism of some activists has frustrated many advocates of police reform, including members of Black communities with high rates of violent crime. In Portland, however, months of bitter spats with authorities have bolstered abolitionists while sidelining—or converting—more moderate voices. Because the Portland Police Bureau relies largely on a specialized rapid-response team for crowd control, the same sixty-odd officers are invariably tasked with breaking up demonstrations. Team members no longer display their nametags—“to reduce the risk of being doxed,” according to a police spokesperson—but the protesters know who several of them are, and the animus on both sides feels deeply personal.

The rapid-response team was deployed at most of the direct actions I attended during four weeks in Portland. Nearly every time, an incident commander announced over a loudspeaker that the gathering had been declared a “riot” or an “unlawful assembly.” Certain nights, this came after vandalism or arson; other nights, protesters had simply impeded traffic. The rapid-response team then attempted to disperse the crowd with some combination of arrests, tear gas, stun grenades, and “less lethal” munitions—either solid-foam pellets or plastic capsules that burst on impact, releasing paint or a chemical irritant. A camper that had been converted into a makeshift ambulance supported a troop of medics embedded with the protesters. Although medics marked themselves with red tape, many had been injured, including one who was hit in the head with a tear-gas cannister, resulting in a traumatic brain injury.

Arrests by the rapid-response team often looked vindictive and gratuitously violent. I saw many officers tackle peaceful protesters and jab them with batons. They kneeled on necks and backs, stepped on faces, and sprayed mace into the eyes of compliant or restrained people. One night, I watched an officer chase an apparently random man, throw him down, straddle his chest, and repeatedly punch him in the face. Oregon Public Broadcasting later reported that the man, Tyler Cox, was a volunteer medic; after he was arrested, for “assaulting an officer,” Cox was admitted to the hospital where he works as a nurse. The incident is under investigation.

Protesters equipped with cell phones and microphones scrupulously recorded abuse and posted footage of it on social media—and after a while this seemed to have become the primary objective. When I asked people to explain the purpose of the direct actions, a common response was that they forced officers to enact on camera behavior that they otherwise denied or concealed. Graphic evidence of police brutality, it was hoped, would win sympathy for the abolitionist cause. The focus on documentation might explain why people sometimes seemed intent on provoking the officers. Before the rapid-response team dispersed a demonstration, its members typically stood in tight formation, surveilling the crowd. Protesters, their voices raw with anger, would unleash a withering deluge of verbal harassment: “Fuck you, piggies!” “Did you beat your wife last night?” “Stick it in your mouth and pull the trigger!”

Once, a young white woman in a red tank top walked up and down a line of officers, pointing at each of them and shouting, “Bitch!” The officers—some of their riot gear colorfully splattered from previous volleys of paint-filled water balloons—gazed silently through their face shields. In July, a Black member of the rapid-response team, Jakhary Jackson, spoke out about his experience of the demonstrations. In a video released by the Portland Police Bureau, he claimed that white protesters had taunted him with racially charged insults, including “You have the biggest nose I’ve ever seen!” Jackson, who majored in history at Portland State University, said that it was galling to be attacked by protesters “who have never experienced racism—who don’t even know that the tactics they are using are the same tactics that were used against my people.”

One mainstay at the demonstrations was a seventy-seven-year-old African-American man named Kent Ford. Easily identifiable in his backward flatcap and red suspenders, he always had an oil painting of Breonna Taylor with him. Holding the painting high above his head, he would march with long, determined strides. One rainy night, Ford wrapped the canvas in plastic bags; the next time I saw him, it was encased in Plexiglas. In 1969, Ford had opened a Portland chapter of the Black Panthers, and he likened the current direct actions to the multiracial Rainbow Coalition forged by Fred Hampton, the Panther leader.

“They’re trying to get this back in the box,” he told me. “But it’s not going back in the box, not this time.”

“Where is it going?” I asked.

“I can’t tell you where. All I know is that the longer we stay out here the better off we are.”

There is no other city in America where a Black man can march on behalf of victims of police violence seven nights a week and be surrounded by devoted allies. After half a century as an organizer, Ford appreciated the immense difficulty of movement-building. Logistical obstacles and internal discord inevitably sapped momentum. When Ford planned demonstrations for the Panthers, so much effort went into preparations that people were exhausted by the time they gathered. The resilience of the Portland protests was rare, and, in his view, isolated moments of ugliness hardly mattered. The direct actions brought leftists together, reinforcing their solidarity; for Ford and others, that was reason enough not to stop. The few times I mentioned detractors, Ford replied, “The dogs bark, but the caravan moves on.”

Throughout history, disparate factions have become allies in the name of antifascism, and, in America, white radicals and Black liberation movements have often found common cause. Fifty years ago, Ford travelled to Oakland, California, to work security at the United Front Against Fascism, a conference organized by the Black Panthers and attended by thousands of Communists, feminists, labor organizers, and other militant leftists—the majority of them white. Mic Crenshaw, the former Baldie, is also a vocal advocate of “broad coalition work, to create a critical mass of people who can fight together.” The Black experience of oppression is unique, but Crenshaw believes that it should be understood as symptomatic of a system that hurts other groups as well, including the white working class. “There has to be self-interest,” he said, speaking about white allies.

A Portland rally organized by the Proud Boys, which the F.B.I. classifies as an “extremist group with ties to white nationalism.” Photograph by Philip Montgomery for The New Yorker

A Portland rally organized by the Proud Boys, which the F.B.I. classifies as an “extremist group with ties to white nationalism.” Photograph by Philip Montgomery for The New Yorker

As the sun set on September 5th, more than a thousand demonstrators gathered on the gently sloping greens of Ventura Park, in East Portland, to mark the hundredth consecutive day of protests. Lines formed at tents and tables where middle-aged supporters distributed free first-aid supplies, helmets, respirators, goggles, and earplugs. There were umbrellas for blocking less lethal munitions and traffic cones for snuffing tear-gas cannisters—tricks learned from Hong Kong activists. Two women pulled a wagon loaded with tall shields constructed from fifty-five-gallon plastic drums.

An African-American man with a keffiyeh draped over his head stepped onto a small stage. Mac Smiff, a thirty-nine-year-old hip-hop journalist with an instinct for rhetorical propulsion, was a frequent and favorite speaker at the protests. “I don’t care if you’re Proud Boy or Patriot Prayer, and I sure don’t give a fuck if you’re a cop or a fed—you’re all the same people,” he told the crowd. “They have different jobs and different roles in their revolution.”

When I met with him later, Smiff told me that, before 2020, he’d never participated in antifascist counter-protests in Portland. “I watched them on the news,” he said. “It had nothing to do with us. At the time, we were, like, ‘That’s the racist white people fighting against the not-racist white people—sounds like a good fight to be had.’ ” Then, on August 22nd, more than a hundred Trump supporters, including Proud Boys, assembled outside the Justice Center for their first major rally in Portland since George Floyd’s death. The theme: “Back the Blue.” Rose City Antifa and PopMob organized a counter-protest. Smiff and his wife, Ri, joined the antifascists. The two sides furiously attacked each other with fists, bats, and bear repellent. Ri, a nurse and volunteer medic, treated more than two dozen people for injuries. The rapid-response team stood by until the Trump supporters retreated. Then an unlawful assembly was declared, and the antifascists were driven from the area with batons and impact munitions.

“It was jarring,” Smiff said of the police intervention. “They were openly taking the side of a hate group.”

Rose City Antifa and PopMob allege that the Portland Police Bureau, which is eighty per cent white, has long tolerated crimes by far-right groups while cracking down on leftist demonstrators. (The police spokesperson denied this, saying that all lawbreakers, “no matter their political alignments,” were subject to arrest.)

At Joey Gibson’s Trump Free Speech Rally, in 2017, a militia member helped officers handcuff and detain an antifascist counter-protester. At a rally the following year, officers discovered four Patriot Prayer supporters on a roof with rifles, but made no arrests. In 2019, the Portland Police Bureau falsely tweeted that antifascists had thrown “milkshakes” filled with quick-drying cement at Patriot Prayer marchers. The story became a viral right-wing meme used to impugn antifascists. Sophie, of Rose City Antifa, said that this apparent track record of bias helped catalyze Portland’s movement to defund the police when Floyd was killed: “There was already a lot of resentment toward the police because of the very clear way that they treated left-wing protesters as the enemy and right-wing protesters as their friends.”

At the same time, activists do not necessarily decry the Portland Police Bureau as an egregious outlier: in their view, it is simply executing the core function of American law enforcement by aligning with white supremacists. For many protesters, the deployment of militarized federal agents to Portland confirmed this. In September, The Nation reported that agents had used classified cell-phone-cloning technology to spy on protester communications, and the Attorney General, William Barr, has since encouraged prosecutors to consider charging violent protesters with sedition.

Trump, meanwhile, has vowed to designate Antifa as a terrorist organization. The only right-wing group for which he has made a similar pledge is the K.K.K. According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, during the Trump Administration right-wing terrorists have carried out about a hundred and forty attacks, left-wing terrorists a dozen. An assessment released by the Department of Homeland Security on October 6th predicted that, in the foreseeable future, white supremacists “will remain the most persistent and lethal threat” to the U.S. Nevertheless, in the first Presidential debate, Trump said, “Almost everything I see is from the left wing.” Technically, this may have been true. A former head of intelligence for the Department of Homeland Security (and a Republican) recently filed a whistle-blower complaint alleging that he faced pressure to downplay the danger of white supremacists and to emphasize that of leftists.

Five days after Michael Reinoehl killed Aaron Danielson, in Portland, he appeared on Vice News, from an undisclosed location, and admitted responsibility, claiming self-defense. Trump tweeted, “Everybody knows who this thug is,” and exhorted law enforcement to “do your job, and do it fast.” That afternoon, near Olympia, Washington, a fugitive task force led by U.S. marshals opened fire on Reinoehl while he sat in a parked car, and then again as he stumbled into the street. Roughly thirty rounds were fired. A gun was found in Reinoehl’s pocket. Multiple witnesses have said that the officers neither identified themselves nor attempted to detain Reinoehl. (At a recent campaign rally, Trump said, “They didn’t want to arrest him.”) After Reinoehl died, Attorney General Barr declared, “The streets of our cities are safer with this violent agitator removed.” Trump added, “That’s the way it has to be. There has to be retribution.”

On August 25th, armed citizens travelled to Kenosha, Wisconsin, where rioting had erupted after a white police officer shot a Black man seven times in the back. During altercations, Kyle Rittenhouse, a seventeen-year-old who’d come to Kenosha from Illinois, killed two people with an assault rifle. He then carried his rifle past police officers while someone yelled, “That dude just shot them!” Though Rittenhouse was later charged with homicide, Trump has defended his actions, and NBC News has reported that Department of Homeland Security officials were directed to make public comments sympathetic to Rittenhouse. (Rittenhouse acted in self-defense, his lawyer says.)

For antifascists, the Reinoehl case is an example of state-sanctioned murder, and the Rittenhouse case shows how extrajudicial killing can be outsourced to civilians. Morgan, the Rose City Antifa member, said, “That’s what to me is uniquely terrifying about this moment. It feels like these far-right groups have basically been given the go-ahead to step in and commit this extralegal violence where the police cannot, but want to.”

Some leftists compare the President’s demonization of dissent to the anti-Communist fervor of the mid-twentieth century. Certainly, the right-wing culture of paranoia that he tirelessly fosters can look like mass delusion. In an August interview with Fox News, Trump spoke of an airplane “almost completely loaded with thugs, wearing these dark uniforms, black uniforms, with gear and this and that,” which he linked to “people that are in the dark shadows” who “control” Joe Biden. The baseless claim echoed the baroque anti-Semitic conspiracy theories of the cult group QAnon, which has gained surprising traction among Republicans, in part thanks to Trump’s tacit approval of it. A week after the President’s plane remarks, wildfires rampaged across Oregon, forcing more than forty thousand people to evacuate and killing nine. Smoke filled Portland’s skies, and activists suspended demonstrations, turning to relief efforts. While some protesters set up a donation point outside a shopping mall, and others delivered supplies to rural shelters, QAnon promoted a false rumor that antifascists had started the fires.

Across Oregon, 911 calls inquiring about Antifa arsonists flooded dispatch services, and checkpoints manned by armed citizens slowed evacuation efforts. During a public Zoom conference, a captain in the Clackamas County Sheriff’s Office related accounts of “suspected Antifa” members felling telephone poles “in the hopes of starting further fires.” The sheriff soon repudiated these reports, but not before a Clackamas County deputy was captured on video telling a local resident, “Antifa motherfuckers are out causing hell.” In a separate video, the deputy warned people that if they killed miscreants they could be charged with murder; however, he advised, if “you throw a fucking knife in their hand after you shoot them, that’s on you.” (The deputy was placed on leave and is under investigation.) Several law-enforcement agencies, including the F.B.I., beseeched citizens to stop spreading the false Antifa stories. But at a rally Trump insisted, “They have to pay a price for the damage and the horror that they’ve caused.” Some critics noted that, in 2018, Trump pardoned Dwight and Steven Hammond—Oregon ranchers who had been convicted of igniting fires on federally managed land.

One day, at the protester-run donation point, I met Gary Floyd, a longtime activist who had just returned from Mill City, an hour south of Portland. Floyd is in the process of registering an official Black Lives Matter chapter in Oregon, and he had filled his trunk with food and water, intending to help evacuees and thereby show them that the organization was nothing to be feared. Outside Mill City, he parked and opened his trunk. Although Floyd has been involved in activism since the Rodney King riots, in 1992, the hate that he encountered took him aback. “I was told to get the fuck out of town and called the N-word four or five times,” he told me. “People were passing by and yelling out their windows at me.”

After Mac Smiff, the hip-hop journalist, finished his speech at the Ventura Park rally on September 5th, an African-American woman took the stage. Protesters would be marching to the Portland Police Bureau’s East Precinct house, she announced. In an arch tone, she reminded the crowd, “We celebrate a diversity of tactics.”

I’d heard variations of the phrase repeatedly in Portland. The maxim was first codified by demonstrators at the 2008 Republican National Convention, in St. Paul, Minnesota: to maintain cohesion among sometimes fractious activists, they urged acceptance of all styles of protest. Effie Baum, the PopMob co-founder, told me, “One of the tools of the state is getting us to create that dichotomy between ‘good protesters’ and ‘bad protesters.’ ” Another popular chant at direct actions was “No bad protesters in a revolution.” The vandalism that I witnessed in Portland was perpetrated by a very small minority, but even fewer people attempted to intervene, and those who did were often disparaged as “peace police.” The result was that the most extreme acts generally set the tone of the demonstrations—a tangible marker of the movement’s ideological drift.

The rapid-response team blocked the road to the precinct house. Near the front of the march, I found Rico De Vera, the engineering student, live-streaming with his cell phone. As we greeted each other, a Molotov cocktail was hurled from the rear and exploded a few feet away, just shy of the officers. Flames splashed protesters, and a man’s leg caught on fire. While medics tended to him, two more Molotov cocktails exploded between us and the officers, who discharged tear gas, stun grenades, and impact munitions, scattering the march. A helicopter hovered overhead. People stumbled into side streets, coughing and retching.

I lost De Vera in the melee but caught up with him a few hours later, on a commercial boulevard. He and another man, a thirty-five-year-old African-American named Jay Knight, were arguing with a white protester in black bloc. De Vera and Knight were angry about the Molotov cocktails; the white protester defended their use.

“If you guys keep playing war games, there’s gonna be an actual war,” De Vera said. “They’re looking for a reason. No one here is prepared for what real war is like. Everyone here will be fucked, and people of color will be especially fucked.”

Knight added, “Molotov cocktails make this side look worse than the cops. It makes people who were on the fence dismiss all of this as criminality.”

The white man muttered something inaudible and walked off. Knight shook his head. “They all use the same argument—‘Oh, a Black person called for a diversity of tactics.’ ” Later, Knight told me, “This needs to stop. It’s become a mockery. When you have Trump using this to be reëlected, it’s, like, ‘O.K., guys, wake up.’ But they don’t care.”

Respect for a diversity of tactics was always intended to strengthen militant activists, not sway moderates. The liberal position that violence and vandalism are undemocratic rings hollow to radical leftists for the same reason that appeals to free speech do: from their perspective, we don’t live in a real democracy, and our speech isn’t truly free. In “Antifa,” Mark Bray points out that millions of incarcerated Americans have been silenced and disenfranchised, and that prison abolitionists want to eliminate “this black hole of rightlessness.” Anarchists, furthermore, “aim to construct a classless, post-capitalist society that would eradicate significant discrepancies in our ability to make our speech meaningful.” However fanciful this may sound, it’s what many antifascists are fighting for, which informs how they fight.

After leaving Knight and De Vera, I followed another group into a neighborhood where a man and a woman peered out from their second-story bedroom window.

“Get away from our cars!” the woman snapped.

Protesters loitered in their driveway. Insults were exchanged. “We’re Democrats, you fucking jerks!” the woman said.

The protesters laughed and moved on.

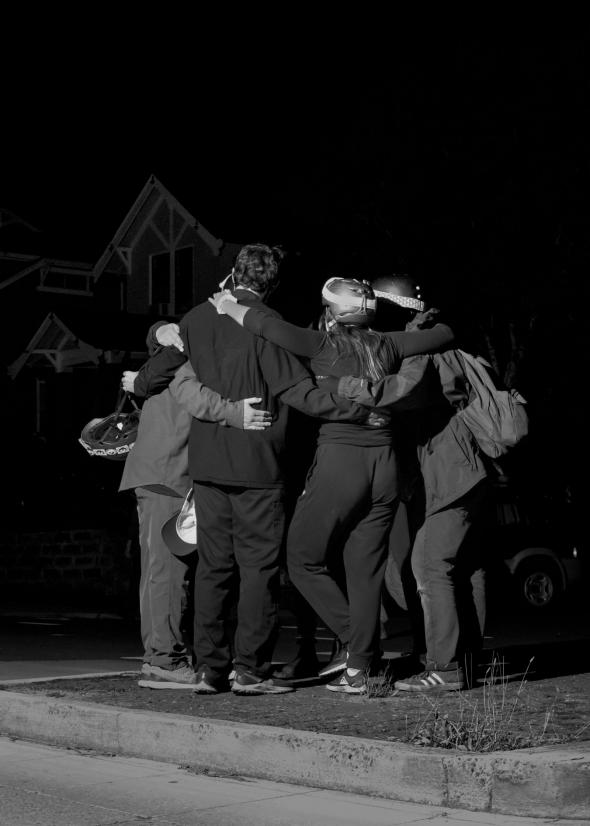

The resilience of the Portland protests is rare, and, in one veteran organizer’s view, isolated moments of ugliness hardly matter. The direct actions bring leftists together, reinforcing their solidarity. Photograph by Philip Montgomery for The New Yorker

The resilience of the Portland protests is rare, and, in one veteran organizer’s view, isolated moments of ugliness hardly matter. The direct actions bring leftists together, reinforcing their solidarity. Photograph by Philip Montgomery for The New Yorker

That afternoon, Joey Gibson and hundreds of Patriot Prayer supporters had held a memorial service for Aaron Danielson in a Vancouver park. Speakers remembered Danielson as a “unifier” with “a huge heart”—“the first guy to buy you a drink if you were having a bad day.” I met a friend of Danielson’s there: a middle-aged man in a Patriot Prayer T-shirt, carrying a longboard and a sidearm. An online-meme creator and “info warrior,” he told me that Antifa answered to George Soros, who collaborated with China, which controlled the United Nations, which had created covid-19 to lead Americans “lockstep into a one-world global-medical tyranny.” He said of Danielson’s death, “We’re a hornet’s nest, and we’ve been kicked. We need to be feared. A central message that we’ve portrayed over and over again is: They must respect us.”

Nonetheless, when Gibson took the stage, he implored the audience not to seek revenge: “I don’t want to see one person going to Portland and committing acts of violence.” The press had shown up, and Gibson seemed eager to cast himself and Patriot Prayer as irreproachably virtuous. He spoke passionately about resisting hate and about the importance of forgiveness. Though he didn’t mention the abuse he had endured the night that Danielson was killed, he pointedly extolled the courageous faith of Jesus, who had “walked straight into death.” Describing Patriot Prayer supporters as embattled victims in a society antagonistic to their existence, Gibson expressed a paradoxical sentiment common among heavily armed Christians: “I’m sick and tired of living a life of fear.”

Later, Rose City Antifa published a photograph, taken at the memorial, showing Gibson with his arm around Chester Doles, a former Imperial Wizard in the K.K.K. Doles went to prison in 1993 for assaulting a Black man, and was arrested again in 2016 for his involvement in a bar fight in Georgia between skinheads and an interracial couple. He recently started a pro-Trump group called American Patriots USA, which, according to Ace, the Rose City Antifa member, “appears to use Patriot Prayer as a template for organizing in Georgia with a similar base.” Ace added that white supremacists like Doles have learned “how to project an image of quote-unquote patriotism while pedalling an extremely hateful ideology.” (In an e-mail, Gibson said of the photograph, “I took pictures with over 50 people that day. I have no idea who he is.”)

After the service ended, a few dozen Proud Boys lingered on the edge of the park, most of them wearing the organization’s signature black-and-yellow Fred Perry polo shirts. (Fred Perry recently denounced the Proud Boys and discontinued production of the polos in North America.) When I approached the group, I was greeted by a man with long graying hair and a thick white goatee, who held the hand of a woman about half his height. “proud boy” was tattooed on his forearm, and he wore a gun on his hip.

His name was David Machado, and he was a sixty-one-year-old Air Force veteran, a retired flight engineer, and one of the first members of the Vancouver Proud Boys. He wanted me to know that he and his wife, Carie, were children of Mexican immigrants. Machado had become involved with Patriot Prayer in 2016 because, like Gibson, he’d felt persecuted for his political and religious beliefs. “If you’re for Trump now, you’re a white supremacist,” he said, incredulous. “We have Mexican kids, Mexican families. It’s just not right.”

“My husband shouldn’t have to tell me that if he’s not with me I can’t wear my Trump gear,” Carie said.

Machado had served as Gibson’s personal security detail at Portland rallies. He’d been hospitalized twice for injuries sustained from antifascists. Activists had posted photographs of him around his neighborhood, on posters that called him a Nazi. Now he never left his house unarmed. “I’m on their hit list,” he said.

While Machado and I spoke, the other Proud Boys left and headed to a nearby bar. Machado nervously scanned the park. “I don’t wanna be out here all by myself,” he told me. It was broad daylight. A couple pushed a stroller across the grass.

But Machado’s concern later proved reasonable. At the bar, a man began filming Machado and his friends with his cell phone. “He was trying to dox us,” Machado said. After a bouncer made him leave, the man ran over a Proud Boy in the parking lot, fracturing his skull and rupturing his eardrum. The man was eventually arrested and charged with a felony hit-and-run. Although he wasn’t a member of Rose City Antifa, he had shared a social-media post advocating violence against racists.

A GoFundMe page was set up to cover the victim’s medical expenses. Gavin McInnes, the Proud Boys founder, who has since distanced himself from the group, contributed a thousand dollars. In the comments section, he wrote, “War.”

The night after Gary Floyd, the Black Lives Matter activist, was shouted at by racists near Mill City, he discussed the impending election with protesters outside a juvenile-detention center in Portland. “It’s going to go one way or the other,” Floyd told them. “Trump gets reëlected, and we are all terrorists—or he don’t get reëlected, and we have ourselves a race war.”

Trump has been openly laying the groundwork to contest the results of the election, and there is widespread concern that he will call upon his supporters to reject them, too. “The only way we’re going to lose this election is if the election is rigged,” he has said. “We can’t let that happen.” During the first debate, Trump wouldn’t commit to discouraging his supporters from engaging in violence while mail-in ballots are counted. When Chris Wallace, the moderator, pressed him to ask white supremacists, specifically, to “stand down,” Trump responded, “What do you want to call them? Give me a name.” Biden brought up the Proud Boys, and Trump answered, “The Proud Boys? Stand back and stand by. But I’ll tell you what, I’ll tell you what. Somebody’s gotta do something about Antifa and the left.”

The Proud Boys were ecstatic. One prominent leader wrote on Parler, “Trump basically said to go fuck them up! This makes me so happy.” Within hours, “Standing By” had become a new Proud Boys mantra, and T-shirts with the phrase were available online.

On September 26th, the Proud Boys came to Portland for a rally against “domestic terrorism,” planned after Aaron Danielson’s death. Organizers expected thousands of attendees from across the country. Governor Kate Brown declared a state of emergency, and a U.S. marshal federally deputized members of the rapid-response team, meaning that, in some circumstances, people accused of attacking them could face enhanced penalties.

The rally turned out to be lacklustre, with a couple of hundred Proud Boys drinking beer in a muddy field. After chants of “Fuck Antifa,” most of the men kneeled while a minister entreated God to “reveal your purpose to the Proud Boys—use us to lift up this city!” Following the prayer, the crowd emitted a communal grunt of “Uhuru!,” the Swahili word for “freedom,” which Proud Boys have co-opted as a satirical battle cry. Speakers blared an electric-guitar solo of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” and a number of Proud Boys, instead of placing their hands over their hearts, held up the “O.K.” sign—a white-power signal. (Some people claim to use the gesture ironically, to inflame liberal sensitivities.) “America, bitch!” someone bellowed. A few Proud Boys sported patches that said “RWDS”—Right Wing Death Squad—and one man wore a T-shirt that featured a portrait of Kyle Rittenhouse framed by the words “the tree of liberty must be replenished from time to time with the blood of commies.”

A welder named Shane, with a bushy red beard and a holstered Beretta, told me that he had driven down from Spokane, Washington, the previous night. Each front pocket of his blue jeans contained a loaded magazine, and in his rear pocket was a copy of the Constitution. Shane had taken part in the August 22nd brawl, when Mac and Ri Smiff joined the militants from Rose City Antifa. “When you have an ideology that is completely antithetical to Western culture and our traditions, we can’t let that go on,” he explained. “It’s a cancer eating away at the soul of America.”

Though Trump’s exaggeration of the threat posed by Antifa is likely a cynical ploy to scare up votes, Proud Boys like Shane and David Machado seem sincerely and deeply worried about Antifa. I asked Shane if he thought that the protesters in Portland represented a significant danger.

“Hundred per cent,” he said. “They fundamentally want to change everything about America.”

It occurred to me that most of the antifascists I met in Portland would readily agree with Shane’s assessment.

After this conversation, I went to Peninsula Park, where hundreds of the people Shane feared listened to Mic Crenshaw compare their fight to his own, three decades earlier, in Minneapolis. Later that night, many of the protesters headed to the Justice Center. The Proud Boys had left Portland without coming downtown, and there was a sense of triumph and relief. Black activists delivered speeches to a peaceful audience; I saw no vandalism. Yet, at some point, the rapid-response team, freshly deputized as federal marshals, arrived with a large contingent of state troopers in riot gear. They stormed the park, assaulting and arresting people. Half a dozen officers dog-piled on a woman, wrenching her arms behind her back. A seventy-three-year-old photographer was thrown to the ground; a journalist was shoved into a tree. Someone was maced at point-blank range. The show of force felt more intense than anything I’d seen in the past month. On this hundred-and-twenty-first day, it could have been a form of desperation—or of vengeance.

Article originally published by The New Yorker, 25/10/2020