Iwalewahaus – Display of Modernist Movements

In 1981, linguist Ulli Beier and artist Georgina Beier established Iwalewahaus in Bayreuth, Germany, bringing along an impressive array of modernist artworks. Their journey began in Nigeria and took them to Papua New Guinea in 1969, where they carefully chronicled and initiated modernist movements and their interconnections, thus bridging art spaces and communities. Ulli and Georgina Beier collected a variety of artworks, textiles, and sculptures, promoting the idea of the independent ‘modern artist’. Working within a colonial framework, they benefited from the artistic expressions born from the colonial legacy and forged aesthetic links between multiple countries. After departing from Germany, they settled in Australia and began archiving their visual memories, which were eventually sent to Iwalewahaus. Their professional legacy has since been digitized and shared with the Centre of Black Culture and International Understanding (CBCIU) in Osogbo, Nigeria. Their collection has been researched in the frame of collaborative research projects and individual PhD topics, questioning Ulli and Georgina Beiers legacy and its inherent dominant narratives as well as contributing to a broader understanding of Modernisms. Currently, Iwalewahaus as an institution still feeds from its initial strategies, trying to navigate between different stakeholders and ethical commitment.1

Introduction

Iwalewahaus is a museum dedicated to modern and contemporary art from Africa, the African diaspora, the Pacific, and Asia. Located in Bayreuth, Germany, it is affiliated with the city’s university. Established in 1981 by linguist Ulli Beier (1922-2011) and artist Georgina Beier (1938-2021), the museum houses a significant collection of over 12,000 artworks.

The Beiers began their art collection journey in Nigeria in 1951 and later continued in Papua New Guinea, carefully initiating and documenting modernist art movements. They relocated to Australia in 1978, where they archived their visual memories until their deaths. Their tenure in Bayreuth spanned 13 years (1981-84 and 1989-97), during which the university acquired their collection in 1980. The Iwalewahaus collection mirrors Ulli and Georgina Beiers’ collecting strategies during colonial times, highlighting a unique aspect of European patronage during the independence era. It showcases power dynamics and features works by artists who blended local crafts and materials with European modernist themes.

In 2012, also the ‘photographic estate’2 of the Beiers was transferred to Iwalewahaus at the University of Bayreuth in Germany from their residence in Australia. This extensive private collection includes about 40,000 items: photographs, negatives, slides, scans, publications, flyers, posters, letters, handwritten notes, recordings, and films. Primarily accumulated and organized by Ulli Beier, who took most of the photographs, the collected materials document their surroundings and positions in their environment. They enrich the Beiers’ visual memory of their residences and supports the narrative they built over the years regarding their cultural work, collective strategies, personal and political agenda. The estate added to the existing art collection, closed gaps and made their collection strategies more evident. It mirrors their search for and realization of a homeland, their ‘Phantasy Africa,’ and demonstrates how their archive served as a projection surface and reference point to materialize this place both physically and psychologically. The Beiers’ search merges a nostalgic view of pre-colonial Africa with the active creation of a ‘modern’ artistic reality. The personalized homeland they constructed in their archive over the years allowed them to ‘transport’ and realize it in different locations, thereby ‘preserving’ it.

Iwalewahaus was envisioned as a self-reflective museum. It was designed to be a space for engaging with artworks and artists closely connected to Africa. In its early years, both Ulli and Georgina Beier played a crucial role in shaping its identity. This included hosting an artist residency program, inviting extended family and friends primarily from Nigeria and Papua New Guinea, and bringing artists from Africa to Bayreuth. Their aim was to transform Western narratives, though these were carefully curated by the Beiers themselves. They named the museum Iwalewahaus3 with its focus on modern and contemporary art.

This article refers to earlier articles, which were embedded in larger research projects and can be seen as a collaborative effort to question the dominant narratives within Iwalewahaus, to ensure the accessibility of the collection and to question structural decision made in the past and present.4 The article is a survey of Iwalewahaus and emphasizes on its beginnings, its underlying strategies and its current challenges.

How to collect Modern Art

To understand the framework of Iwalewahaus as an institution in its progressive yet self-centered approach in the 1980s and 1990s, one must revisit the personal and collective strategies of its founders and their co-shaping of a specific Nigerian Modernism.

European art patrons and collectors had a profound impact during Africa’s period of independence. They were instrumental in founding schools, galleries, and collections focused on both traditional artifacts and modern and contemporary art (Fall and Pivin 2002; Förster and Kasfir 2013; Kasfir 1999; Probst 2011; Savage 2014; Okeke-Agulu 2015). The Beiers’ collecting efforts in Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, and Germany were particularly intertwined with the colonial experience and the Nigerian independence movement, where they spent significant time in the 1950s and 1960s. Their form of art patronage reflected a broader trend among privileged Western expatriates in Africa, who sought to find a new identity and believed they could influence and shape their surroundings (Greven 2021).

Nigeria – Setting the Framework

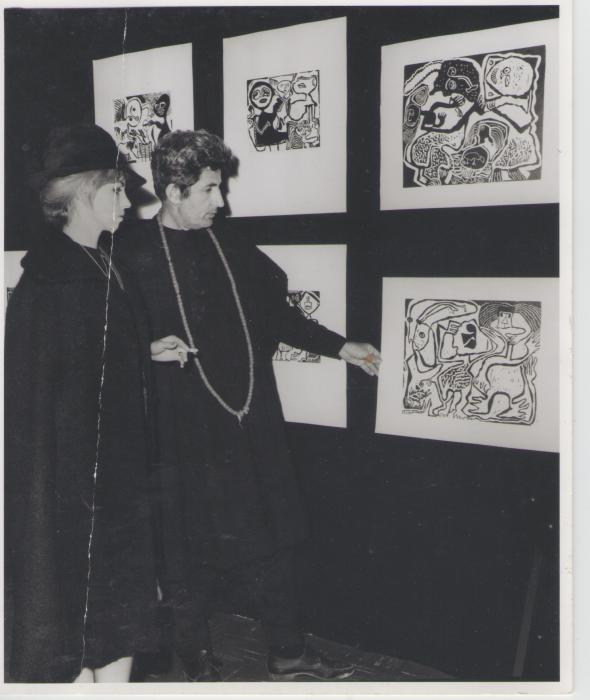

Georgina and Ulli Beier at the Berlin Theatre Festival in 1964.© Centre for Black Culture and International Understanding (CBCIU), Osogbo, Nigeria & Iwalewahaus, University of Bayreuth.

Georgina and Ulli Beier at the Berlin Theatre Festival in 1964.© Centre for Black Culture and International Understanding (CBCIU), Osogbo, Nigeria & Iwalewahaus, University of Bayreuth.

Ulli and Georgina Beier approached Nigeria as self-identified outsiders, embracing roles that set them apart from the established social and cultural norms. They also constructed a very specific image of Africa, which they actively shaped not only through founding institutions and workshops, but also in the way their family lived (Greven 2021). Life in Nigeria resonated with them, which they adapted to and, in many ways, influenced and embraced. Ulli Beier delved into his new surroundings through his photography, fully engaging with his life beyond his university duties. At the same time, Georgina Beier immersed herself in community cultural activities, which helped define her artistic journey (Tröger 2001; Okeke-Agulu 2013; Greven et al. 2022).

Ulli Beier started teaching English phonetics at the University of Ibadan in 1950, employed by the British colonial government. In 1951 he changed to the Extramural Department, where he could give courses throughout Western Nigeria, teaching the students about their own heritage, or what he perceived as their heritage. He tried to work not only against the colonial academic curriculum but also to restore the confidence of his students and their belief in their own culture, or what he declared to be their culture. This effort framed his work from the beginning. In his lectures he introduced critical European texts about modern Western civilization, but also included African poets (mainly those associated with Négritude) in his curriculum that portrayed Africa positively. With European staff members he perceived himself as an outsider and redefined himself by becoming a close friend and collaborator of the Nigerian intellectual and artistic elite; he played an active part in forming Nigerian culture in the years after independence rather than being a commentator or observer of it.

His engagement with the artistic scene in and around Nigeria is exemplified by the establishment of two Mbari Clubs (one in Ibadan in 1961, the other in Oshogbo in 1962) as well as by co-founding the art and literature journal Black Orpheus in 1957. Beier had learned the local language of Yoruba and translated oral narratives into English to make them accessible to a bigger audience.

He was not an artist and never saw himself as one, and therefore didn’t place his own artworks in relation to his collection. But he did extend this relationship to Susanne Wenger, his first wife, and Georgina Beier, his second wife, who were both artists and had their very own relationship to Nigerian modernism - or rather played an important part therein. Beier even considered Wenger as the first modern local artist (Beier 1994, 17), but this is disputable despite her role in Oshogbo’s New Sacred Art movement, which developed its own connection towards Yoruba heritage (Naumann, forthcoming).

Beier wrote under pseudonyms such as Sangodare, which was given to him by Yoruba friends. For him, this was a sign of how close he was with the Yoruba community and “the decision to publish some of his critical writings as Akanji or Aragbabalu and his creative work as Ijimere appears to be part of Beier’s strategy of inserting his polemical voice into the discourse of Nigerian art and literature, without drawing attention to his identity as a foreigner” (Okeke-Agulu 2015, 300). The texts Beier wrote during his years in Nigeria clearly reveal how he embedded himself within the local artistic and intellectual world. He was more active as a mediator within the artistic scene and later also with the link between Africa and Europe at a time, when artists and writers were highly engaged with the question of national identity and how this could be transformed, in terms of style and matter, into the arts. This led to the formation of a postcolonial version of Nigerian modernism that was aware of both its own modernity and of the local traditions (Okeke-Agulu 2015).

Georgina Beier played a crucial role in defining the visual identity of Black Orpheus, establishing deep connections with artists and infusing every exhibition, gathering, and residency of the Beiers with a unique sensory quality. When she arrived in Osogbo in 1959 at the age of twenty-four, she was eager to dive into the vibrant local art scene. Her workshops promoted spontaneity and intuition, allowing artists to reinterpret traditions in new and individual ways. This approach is exemplified in her collaborations with artists like Afolabi and Ogundele (s. Okeke-Agulu 2001). The similarities between their early works and Beier’s pieces demonstrate the closeness of their interactions and the mutual influence they had on each other’s artistic development.

A document in her archive titled “A Short Survey of Yorubas and Papuan New Guineans Who Began Their Careers in Georgina’s Studio: The Diversity is Astonishing. 1963–1978 Vol. 34” highlights her role in supporting other artists’ careers; however, it fails to capture the depth and sensuality with which she engaged with artists and her surroundings. Beier was deeply involved with the Mbari Mbayo Club in Osogbo, its workshops, and the theater group, where she designed stage sets and costumes for productions based on Yoruba mythology, integrating visual arts with performing arts (Fig. 2). Her primary artistic endeavors extended beyond these activities, as she created a series of murals in and around Osogbo and Benin City and designed book covers for Mbari publications. These projects, while connected to the community, her partner, and other artists, were part of a broader sphere of her work.

In Osogbo and later locations, Beier collaborated with fellow artists, designed home interiors, crafted clothing for her family, and managed everyday tasks such as shopping and cooking. Her collaborative efforts and social interactions, whether through workshops or business ventures, allowed her to fully engage with her surroundings and build a sense of home and belonging. Although Beier continued to produce art later in life, her time in Osogbo was particularly significant. It was here that she discovered her artistic identity within a vibrant community, where mutual influence and an ideal environment for living and creating shaped her work and personal experience (Greven et al. 2022).

Fig. 2 Georgina Beier’s backdrop for the theater group of Duro Ladipo (here with Abiodun Ladipo),unknown date

Fig. 2 Georgina Beier’s backdrop for the theater group of Duro Ladipo (here with Abiodun Ladipo),unknown date

[© Centre for Black Culture and International Understanding (CBCIU), Osogbo, Nigeria &Iwalewahaus, University of Bayreuth.Georgina Beier’s backdrop for the theater group of Duro Ladipo (here with Abiodun Ladipo),unknown date.© Centre for Black Culture and International Understanding (CBCIU), Osogbo, Nigeria &Iwalewahaus, University of Bayreuth]

This multifaceted approach facilitated a rich interplay between different artistic traditions and contemporary expressions. Her reinterpretation of traditional crafts was particularly evident in her work with Yoruba pottery in Ile-Ife. In Ile-Ife, she studied Yoruba pottery, established a museum with over 300 works, and designed new doors for the building. Beier created shops like Iya Mapo in Ile-Ife and Hara Hara Prints in Papua New Guinea, teaching women artists batik and printing techniques while providing economic opportunities. Her public art projects, including large sculptures in both locations (Fig. 3), incorporated local myths and pre-colonial structures.

![Fig. 3 [Georgina Beier’s iron installation on the wall of the Institute of Papua New Guinea Studies in Port Moresby, 2024. © Katharina Greven] Fig. 3 [Georgina Beier’s iron installation on the wall of the Institute of Papua New Guinea Studies in Port Moresby, 2024. © Katharina Greven]](https://www.buala.org/sites/default/files/imagecache/full/2024/10/fig3.jpg) Fig. 3 [Georgina Beier’s iron installation on the wall of the Institute of Papua New Guinea Studies in Port Moresby, 2024. © Katharina Greven]

Fig. 3 [Georgina Beier’s iron installation on the wall of the Institute of Papua New Guinea Studies in Port Moresby, 2024. © Katharina Greven]

In Papua New Guinea, Beier immersed herself in the culture, learning Pidgin English and establishing the Centre for New Guinea Cultures and Gambamuno Gallery. She focused on empowering local artists, working with the Village Development Task Force and mentoring individuals like Mathias Kauage. Beier’s approach extended to transforming living spaces into artistic environments, exemplified by her home in Ile-Ife, which showcased her designs and the works of artists she mentored. Throughout her career, Beier successfully bridged traditional and contemporary art forms, empowering local artists and making art an integral part of everyday life across different cultures.

The Beiers’ collecting journey began in 1950 during Ulli Beier’s time in Nigeria with his first wife, Susanne Wenger. While working with patients at the Lantoro Mental Home in Abeokuta, they recognized the artistic potential of these individuals, whom Ulli Beier later referred to as artists (U. Beier 1959). This early experience was pivotal in shaping their cultural activities and collecting strategies. At that time, both Beiers sought to discover an “unspoiled” form of artistic expression, distinct from European artistic traditions. They believed that these artists could produce highly original work because they were free from the constraints of Western education and social pressures (U. Beier 1959, 30). The Beiers’ vision for the ‘modern artist’ in Nigeria, and later in Papua New Guinea, stems from the initial visit in Abeokuta, emphasized working with new materials and maintaining a detachment from traditional materials, which often held specific social functions. They encouraged artists to bypass academic or cultural conventions, relying instead on their intuition and blending reality with fantasy (U. Beier 1960; G. Beier 1977; Okeke-Agulu 2013; 2015).

In Ibadan and particularly in Osogbo during the early 1960s, their initiatives aimed to support emerging ‘modern artists.’ The Mbari Clubs exemplified this by promoting (1) ‘modern artists’ from academic backgrounds (in Ibadan) who challenged conventional curricula, and (2) “outsider artists” from Osogbo who remained supposedly unaffected by academic influences.

For the Beiers, two forms of authenticity were relevant for their understanding of the arts from “elsewhere”: the authenticity of the traditional art, which U. Beier felt obliged to save or rescue through his photography, his writings and to some extent through museums and collaborative art processes, and the authenticity of modern art, which in his view was innovative but not completely detached from its traditional predecessors. Here, tradition was used as an inspiration rather than a cultural determination (Greven 2021). This is reflected in the three museums the Beiers founded in Nigeria: The Antiquity Museum and Museum of Popular Art in Oshogbo and a pottery museum in Ile-Ife.

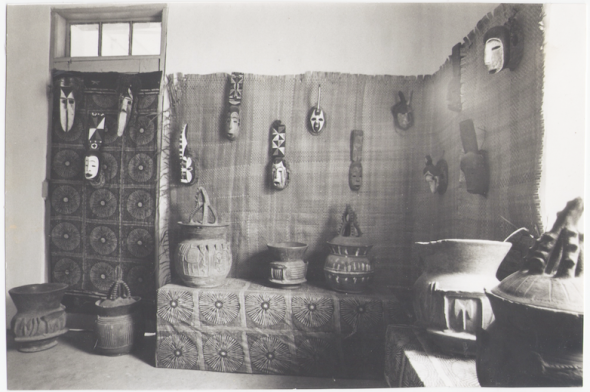

Fig. 4 Interior view of the Antiquity Museum in Osogbo, unknown date. © T. Beier

Fig. 4 Interior view of the Antiquity Museum in Osogbo, unknown date. © T. Beier

For the Antiquity Museum (Fig. 4), they collected artefacts and displayed them in a non-ethnographic way, focusing on their forms without social or historical contextualization, and was influenced by a nostalgic view formed by pre-colonial fantasy. Although his idea of the unspoiled Africa appeared to be an emotional attitude, his work in the museum was pragmatic. The artefacts became part of a local heritage and therefore gained a different value. By exhibiting them, the artefacts were intended rather to inspire than to conform them. They might have sparked local artists to find a new interest in traditional forms, but by declaring the artefacts as antiquities, Ulli Beier historically framed the objects and reintroduced them as a source of inspiration for the artists without forcing them to follow traditional forms in their modernist production. Thus, the artefacts changed function: they became a source of knowledge and provided a new awareness of cultural heritage.

The Museum of Popular Art primarily showed works by academically untrained artists who also fit into their definition of ‘modern artists’, “[…] whose work showed a formal or conceptual synthesis of modernist avant-garde techniques and the sense of enigma he identified with indigenous art and religions in Africa. Such work must at once be formally expressive and intuitive rather than deliberate or mannered but also suggestive of some indeterminate spirituality and indirectly evocative of Western modernist and indigenous African artistic traditions” (Okeke-Agulu 2015, 136-137). This understanding of the ‘modern artist’ profoundly influenced the Beiers’ selection of artists and the development of their art collection over the years.

Papua New Guinea

Ulli and Georgina Beier left Nigeria in 1966 due to the imminent Biafran War and moved to Port Moresby in 1967, with a second relocation in 1974. They continued their work from Oshogbo and Ile-Ife during their second stay in Nigeria from 1971-1974. In Papua New Guinea, they visited the Laloki Mental Hospital, launched the magazine Kovave, and applied their concept of the ‘modern artist’ – akin to their approach with Black Orpheus. They designed their house, which doubled as a cultural center, and worked to preserve traditional paintings from decay and loss. Ulli Beier’s curriculum aligned with his previous work in Ibadan, while Georgina Beier collaborated closely with local artists, selecting whom to work with and influencing the collection’s contents.

Their efforts aimed to document and potentially revive cultural practices they felt were at risk of disappearing, anchoring them in local cultural memory. Ulli Beier found the environment in Papua New Guinea similar to Nigeria, reinforcing his ideas and observations about traditional and modern art, as well as colonial influences. However, the roles of the Beiers shifted in Port Moresby: Ulli Beier struggled to connect with the local population, whereas Georgina Beier, as in Nigeria, quickly integrated by working closely with locals. Her more prominent presence in publications and projects from this period suggests her role became more established. While her views often aligned with Ulli Beier’s, she explored different aesthetic concepts and terminology, such as through discussions with local artists (see G. Beier 1974).

Despite having numerous photographs and works related to Papua New Guinea, the collection is notably smaller compared to their extensive body of work from Nigeria and not yet researched. This discrepancy reflects not only the shorter time of eight years the Beiers spent in Papua New Guinea compared to the twenty years U. Beier spent in Nigeria, but also highlights Nigeria’s deep physical and psychological significance for both Ulli and Georgina Beier5.

Australia

The Beiers first moved from Papua New Guinea to Sydney for two years in 1978. They returned to Sydney in 1984, staying until 1989, and then moved there permanently in 1997. During their second and third stay in Sydney from 1984 onwards, they transformed their private residence at 46 Johnston Street into Migila House, a cultural center named after a after the Kilivila word for ‘creativity’ and ‘expression’. Migila House became a vibrant cultural hub, hosting exhibitions, music programs, and artist residencies, including artists from Nigeria and Papua New Guinea. It blended living space, exhibition venue, concert hall, and reading stage, and served as an active archive of their experiences in Nigeria and Papua New Guinea. During their Australian years, their collaborative efforts waned. Georgina continued her artistic work, inviting close friends like Mathias Kauage, Muraina Oyelami, and William Onglo for residencies. Community and participation were central to her artistic identity, and the less interaction she had, the less she created. Documents in the National Archives of Australia reveal detailed records of the Beiers’ activities, highlighting their ongoing connections with artists from Osogbo and Papua New Guinea. These archives include lecture notes, correspondence with artists and politicians, and documentation of events at Migila House, emphasizing the collaborative nature of their work.

Despite their efforts, their cultural activities in Australia did not reach the intensity of their earlier work in Nigeria and Papua New Guinea. Their engagement with Aboriginal art, which they saw as aligning with their concept of Outsider Art, reflected their continued interest in art forms outside ‘mainstream’ Western influences. The Beiers’ notion of the ‘modern artist’ remained central to their work, emphasizing artistic freedom from traditional norms and market pressures. Sydney became the final home for the Beier family. Over time, the activities at Migila House diminished. Georgina Beier lived alone in Sydney after U. Beiers death, often reminisced about Osogbo and the Yoruba community, reflecting on a time when she felt a strong sense of belonging and impact (Greven 2021).

Iwalewahaus today

The Iwalewahaus was seen and realized as a combination of the Beiers’ experiences, an ‘organic whole’ which reflected not only their collective strategies but their personal search of a home. The Iwalewahaus (Fig. 5) was established to bolster the African Studies department at the University of Bayreuth and strengthen its presence in the region. The university president offered Ulli and Georgina Beier the opportunity to purchase their collection and appoint Ulli Beier as the director and curator of a museum dedicated to African art. Initially, Ulli Beier declined the offer but later accepted when he realized it allowed them to bring their vision of a museum and gallery to life. As U. Beier explained in 1982: “Here we want to show how African art has developed through interchanges with – as well as in opposition to – European art forms and artists. More than political manifestos, the arts of Africa reveal the African fight for independence, the reevaluation of tradition, the conflict with European ideas, and the search for identity” (U. Beier 1982, 4).

https://www.buala.org/sites/default/files/imagecache/full/2024/10/fig5-c..." alt="Fig. 5 Iwalewahaus in Münzgasse, Bayreuth, Germany, date unknown. © Centre for Black Culture and International

Understanding (CBCIU), Osogbo, Nigeria Iwalewahaus, University of Bayreuth." width="590" height="375" />

U. Beier aimed to shift the Eurocentric perspective, bringing what was considered peripheral into the center. This approach positioned African art in opposition to the Western narratives that relegated traditional images to ethnographic museums, viewing them as the only authentic representations (Ogundele 2003; Mutumba 2012; Greven 2021). As Beier put it, he had long criticized museums as mausoleums and was keen to create something distinct from the existing institutions filled with stolen objects (Ogundele 2003, 214). The Iwalewahaus initially facilitated a promising dialogue, with artists frequently interacting with the Beiers. This university-supported integration of artistic and academic practice theoretically paved the way for an interdisciplinary and international discourse. However, the presence of artists and researchers from the ‘Global South’ in Bayreuth, seeking to rebuild their own narratives, posed challenges.

The institution primarily reflected the Beiers’ personal perspectives on non-Western cultures, especially Nigeria, thereby reinforcing a hierarchy of knowledge. Ulli Beier’s self-portrayal as an outsider and connoisseur of the arts hindered a truly democratic dialogue. Even acknowledging the artists’ agency in pursuing their own agendas (e.g., through invitations to the Iwalewahaus, marketing their works, reuniting with old friends), Ulli Beier, with Georgina’s consultation, determined who to invite, which seminars to offer, and which exhibitions to host. “Thus, always, the contact zone is an asymmetric space where the periphery comes to win some small, momentary, and strategic advantage, but where the center ultimately gains” (Boast 2011, 66). The dominant narrative centered on Ulli, largely excluding Georgina’s contributions as an artist, still influences the Iwalewahaus.

In 2012, the photographic estate of the Beiers was transported to Bayreuth for digitization, with its ultimate destination being the Centre of Black Culture and International Understanding (CBCIU) in Osogbo (Greven and Naumann, 2024). In 2014 the Iwalewahaus relocated. This move to a new building involved the meticulous task of wrapping and packing every item in the art collection and photographic estate in foil and cardboard (Fig. 6). This extensive process brought to light an important question: who should have access to the archive and its associated knowledge?

Fig. 6 Packed objects of the art collection at the Mash Up Festival in 2013. © Katharina Greven

Fig. 6 Packed objects of the art collection at the Mash Up Festival in 2013. © Katharina Greven

While moving locations the project Mashup the Archive started (2013-2015) under the lead of Dr. Nadine Siegert and Dr. Sam Hopkins. The project was meant as a curatorial intervention to unlearn and produce new knowledge through artistic research, working with pieces from the collections (Hopkins and Siegert 2015). This experience marked a significant shift for the institution. Unpacking the collection and the archive—both physically and conceptually—revealed that personal connections and ownership of the material were less significant than previously thought. It became increasingly apparent that engaging collaboratively with the archive could reshape personal narratives and challenge established perspectives. The archive and collection, rich with intertwined agents and histories, function as spaces where knowledge is both created and negotiated collectively. This emotional and sensory engagement led to new narratives, freeing the material from its embedded histories6.

These two events, the arrival of the estate and Mashup the Archive were the start of several individual and collective research projects, which addressed the history of the collection and questioned Beiers’ heritage and approach7: In 2015 the research project “African Art History and the Formation of a Modern Aesthetic: African Modernism in Institutional Art Collections Related to German Collecting Activities,” funded by VolkswagenStiftung, focused on the history of modern as an entangled history and how these processes are mirrored in collections and archives. The project aimed to investigate both individual, partially privately founded collections currently housed in museums and universities and to explore the historical and contemporary connections between them. This was achieved by examining these collections as networks and through detailed analyses of the ‘biographies’ of individual artworks. The photographic estate of the Beiers served as a central source and resource for this research (Greven et al. 2018), deepening the long-lasting relationship with the CBCIU (Centre for Black Culture and International Understanding) in Osogbo, the rightful owner of the estate, where it was relocated to in 2020 (Greven and Naumann, 2024).

Further interest in the collection and its accessibility at that time lead to research projects such as Exodus Stations, which critically examined heritage and the history of material culture museums through contemporary art. The project involved research and artistic endeavors in natural history, history, ethnology, and cultural artifact museums. Contemporary artists delved into these museums’ photographic archives, exploring how these institutions have contributed to knowledge production. The project resulted from collaborations between artists, museum curators, and researchers, focusing on how historical objects have been politicized, valued, stored, transmitted, and used. It served as a tool for institutional self-evaluation, addressing cultural and historical narratives and public education. The outcomes were showcased through installations, screenings, talks, and workshops in museums, encouraging viewers to reconsider historical interpretations (Jecu 2018)8.

Private yet collaborative PhD projects took and take place up to today, such as the dissertation of the author The archive as a place of belonging – The ‘Phantasy Africa’ of the art patron Ulli Beier and the artist Georgina Beier (Greven 2021), an in-depth research with and within the estate of the Beiers, their construction of the modern artist and their personal search for a place of belonging.

Ongoing dissertations dealing with the collection, its beginnings and its current usage are: (1) The disabled artwork within the Iwalewahaus collections (Böllinger, forthcoming), which focuses on disability, specifically exploring the creations of patients from the former Lantoro Mental Home in Abeokuta (now the Federal Neuropsychiatric Hospital Aro Abeokuta). This collection, comprising more than 600 works, is the only one within the Beiers’ collection, aside from a few individual pieces, which originate from the colonial context of Nigeria in the early 1950s. A significant portion of this collection is housed within various holdings of the Iwalewahaus. (2) New Sacred Art – The work of Susanne Wenger within the context of Nigerian Modernism (Naumann, forthcoming), focusing on the importance of the Austrian artist Susanne Wenger not only for the collective strategies of the Beiers but also for the New Sacred Art Movement in Osogbo.

These projects had and have all common goals: To question the current narratives around the collection, to promote ethical practices with its materials and in collaboration with the respective communities, to ensure visibility and therefore access to the collection, a decolonial effort with our partners. Despite these efforts the accessibility and visibility has been reduced due to structural decisions (e.g. fewer human resources, different alignments) and due to the lack of human resources. It is urgently needed to open the collections for further (artistic) research, to ensure collaborations, producing collaborative knowledge and questioning the location of some of these artworks from an ethical and moral standpoint.

Iwalewahaus was and currently is a critical, processual, performative, socially engaged and transdisciplinary platform that also questioned historical narratives through committed employees. It is hoped that it will continue to further develop into a decolonial and inclusive museum and continue to push even its boundaries.

References

Abiodun, Rowland. 1983. “Identity and the Artistic Process in Yoruba Aesthetic Concept of Iwa.”

Journal of Cultures and Ideas (1): 13–30.

Abiodun, Rowland. 2001. “Yoruba Values: A Conversation Between Rowland Abiodun Und Ulli Beier.”

In Character Is Beauty: Redefining Yoruba Culture and Identity, edited by Wole Ogundele, Olu

Obafemi, and Femi Abodunrin, 247–60. Trenton, Asmara: Africa World Press.

Abiodun, Rowland. 2014. Yoruba Art and Language: Seeking the African in African Art. New York:

Cambridge.

Beier, Georgina. 1974. “Modern Images from Niugini.” Kovave Special Issue, 1–60.

- 1977. Outsider in the Third World: Discussion Paper 23. Port Moresby: Institute of Papua New Guinea Studies.

Beier, Ulli. 1959. “Two Yoruba Painters.” Black Orpheus (6): 29–32.

- 1960. Art in Nigeria 1960. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Univ. Press.

- 1982. Papunya - Moderne Malerei Von Australischen Ureinwohnern. Bayreuth: IWALEWA-Haus.

- 1994. The Return of Shango: The Theatre of Duro Ladipo. Bayreuth: Iwalewahaus.

Boast, Robin. 2011. “NEOCOLONIAL COLLABORATION: Museum as Contact Zone Revisited.” Mus

Anthropol 34 (1): 56–70. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1379.2010.01107.x.

Böllinger, Sarah. Forthcoming. “The disabled artwork within the Iwalewahaus collections.” PhD diss. University of Bayreuth.

Fall, N’Goné, and Jean L. Pivin, eds. 2002. An Anthology of African Art - the Twentieth Century. New

York, NY: Distributed Art Publishers.

Förster, Till, and Sidney Littlefield Kasfir, eds. 2013. African Art and Agency in the Workshop (African

Expressive Cultures). African Expressive Cultures Ser. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/kxp/detail.action?docID=1144290.

Greven, Katharina. Das Archiv als Heimat - Die ‚Fantasie Afrika’ des Kunstpatrons Ulli Beier und der Künstlerin Georgina Beier. Bayreuth: Universität Bayreuth, 2021.

https://epub.uni-bayreuth.de/5798/

Greven, Katharina and Nadine Siegert. 2018. “Why collect African Art? Two Collector’s Biographies.” In Exodus Station #3, edited by Marta Jecu, 26-31. Bayreuth: Universität Bayreuth/ Iwalewahaus.

Greven, Katharina, Lena Naumann, Siegrun Salmanian, Nadine Siegert. 2018. “Collectivize (Re)Sources: The Photographic Estate of Ulli Beier.” Critical Intervention 12 (2): 140-157, 2018.

Greven, Katharina, Lena Naumann, Iheanyi Onwuegbucha. 2022. “Women in Mbari – (Re)Discovering Three Artistic Practices.” In Black Orpheus: Jacob Lawrence and the Mbari Club, edited by Ndubuisi Ezeluomba and Kimberli Grant, 83-95. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Greven, Katharina and Lena Naumann. 2024. “On Access and Responsibility – Questioning Ulli Beier’s Legacy Through Collaborative Approaches.” In Knowing / Unknowing: African Studies at the Crossroads, edited by Katharina Schramm and Sabelo Ndlovu, 171-192. Bosten, Leiden: Brill.

Hopkins, Sam and Nadine Siegert. 2017. Mashup the Archive. Berlin: Revolver.

Jecu, Marta, ed. 2018. Exodus Station #3. Bayreuth: Universität Bayreuth/ Iwalewahaus.

Kasfir, Sidney Littlefield. 1999. Contemporary African Art (World of Art). London: Thames & Hudson.

Lawal, Babatunde. 2005. “Divinity, Creativity and Humanity in Yoruba Aesthetics.” Literature and Aesthetics 15 (1): 161–174.

Mutumba, Yvette. 2012. Die (Re-)Präsentation zeitgenössischer afrikanischer Kunst in Deutschland. ifa-Studien. Stuttgart: Inst. für Auslandsbeziehungen.

Naumann, Lena. Forthcoming. “New Sacred Art – The work of Susanne Wenger within the context of Nigerian Modernism (working title).” PhD diss. University of Bayreuth.

Ogundele, Wole. 2003. Omoluabi: Ulli Beier, Yoruba Society and Culture. Bayreuth African Studies

Series 66. Bayreuth: Universität Bayreuth.

Okeke-Agulu, Chika. 2013. “Rethinking Mbari Mbayo: Osogbo Workshops in the 1960s, Nigeria.” In African Art and Agency in the Workshop, edited by Sidney Littlefield Kasfir and Till Förster, 154–69. African expressive cultures. Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press.

- 2015. Postcolonial Modernism: Art and Decolonization in Twentieth-Century

Nigeria. Durham: Duke Univ. Press.

- 2001. „Passion for Life: Georgina Beier’s Recent Paintings.“ Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, Nr. 13/14: 92-95.

Probst, Peter. 2011. Osogbo and the Art of Heritage. African Expressive Cultures. Bloomington Ind. Indiana University Press. http://gbv.eblib.com/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=713699.

Savage, Polly, ed. 2014. Making Art in Africa: 1960-2010. Farnham: Lund Humphries.

http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=43741.

Tröger, Adele. 2001. “A Short Biography of Georgina Beier.” In Georgina Beier, edited by Rowland

Abiodun and Georgina Beier, 9–58. Nürnberg: Verlag für moderne Kunst.

- 1. This article is an accumulation of collaborative research and published articles, which I will refer to within the text. I especially want to mention and thank Dr. Nadine Siegert, with whom I wrote the first version of this text, published in 2018 (Greven and Siegert 2018).

- 2. In the following referred to as the ‘estate‘.

- 3. ‘Iwalewa’ describes a Yoruba philosophical concept; it can be translated as “character is beauty”, where beauty means not only the purely physical appearance but the inner essence of every creature (Abiodun 2001, 2014; Lawal 2005): “Each creation, be it divinity, person or thing, possesses its own beauty as a necessary consequence of ìwà” (Abiodun 1983, 15).

- 4. I especially wish to acknowledge my colleagues from the VolkswagenStiftung project “African Art History and the Formation of a Modern Aesthetic”: Lena Naumann, Katrin Peters-Klaphake, Siegrun Salmanian, and Dr. Nadine Siegert. Additionally, I extend my gratitude to my current research partner, Sarah Böllinger, with whom I have collaboratively researched, published, and deliberated on the ethical utilization of the archive under study.

- 5. Currently

- 6. https://www.kulturstiftung-des-bundes.de/de/projekte/bild_und_raum/detai...

- 7. This article highlights only a few of the projects that have taken place in recent years.

- 8. https://exodusstations.com/about/