Portugal, Race and Memory: a Conversation, a Reckoning

Producing the Fiction of Unmarked Whiteness:

Unarchiving Race and the Making of Difference in Portugal

The issue of race in colonial and postcolonial Portugal is not only critical to historians, anthropologists, as well as any other researchers and activists, it is also prescient and deeply urgent to our contemporary moment. Despite the role played by the routinized, bureaucratic pursuit of “blood purity” in Portugal – both prior to, and alongside the development of the transatlantic slave trade – race continues to be treated as an entirely foreign and exogenous category. Consequently, race is not only viewed as something imported and that only existed in the colonies, but also as an entirely illegible and inapplicable idea both to the Portuguese past and present. However, be it in the early modern period as well as in our contemporary moment, race remains not only a meaningful category autochthonous to Portugal but also a valid concept both in the past as well as today.

By way of elucidating this point, my narrative will hinge on four, critical acts.

Act 1: The Fiction of Unmarked Whiteness

In the early modern period, Lisbon was the Black capital of Europe. This statement is supported both by historical and numerical research – as well as paintings, religious iconography i.e., Black saints, and foreign travelers’ accounts relaying disbelief, puzzlement, and sometimes even some horror. Black life was ubiquitous, yet the way it is selectively discussed remains problematic. Take for example the painting, O Chafariz d’El Rei. There is, of course, nothing inherently wrong with the painting itself; however, the way both art and images are frequently deployed to build narratives of Lisbon as “the first global capital” is, in fact, deeply fraught with acritical adherences to the triumphalism of empire, capitalism, and the telos of modernity.

The Chafariz d'El-Rey (King's Fountain) in the Alfama District, Lisbon. Netherlandish, ca. 1570. Wikipedia

The Chafariz d'El-Rey (King's Fountain) in the Alfama District, Lisbon. Netherlandish, ca. 1570. Wikipedia

Moreover, emphasis on iconography, while important as a visual tool allowing us to effectively see and not just imagine Black life in Lisbon, frequently resulted in a tendency to instrumentalize blackness as mere “presence” and Black subjects as curiosities to point out but not analyze in any depth. Sometimes, this exercise was retrofitted into narratives of a raceless or colorblind past, typical of lusotropicalismo, thus projecting the myth of a racially harmonious past onto those materials. Instead, my use of “Black capital” aimed to cause an impact. It aimed, specifically, to invite us to consider the scale, the variety, and the many textures and nuances that undergirded experiences of Black life in Portugal – both then and now.

However, rather than discarding images, above all, it is important to insist that they are merely part of a whole; as neither just discrete curiosities we can mobilize and promptly forget, nor as the simple confines of the only reality we are willing to recuperate. Instead, images invite us to unpack triumphalist narratives of early modern “cosmopolitanism” by lending texture, complexity, as well as an entryway into novel, alternative imaginaries. A deeper engagement with the polyphony of the past can, in other words, help us denaturalize the present, thereby forging a new, collective imaginary replete with more diverse human landscapes.

But there is more. In particular, I want to address Ruth Frankenberg’s idea of “the mirage of unmarked whiteness.”1 As she notes, while classic texts in the fields of critical race studies and ethnic studies centered the idea that whiteness was a fundamentally unmarked quality, that notion is, in fact, a fiction – and a very successful one, at that. Indeed, according to Frankenberg, race is “arguably the most violent fiction in human history” (p. 72). Still, while the idea that whiteness is either invisible or unmarked appears at first as a truism, upon closer inspection it is revealed as a mirage. Rather, as Frankenberg proposes — and I, in this text, concur — whiteness is itself a mark. To explore this seeming paradox, i.e., how whiteness was both marked and unmarked category, I want to center on two operable, early modern definitions of race.

The first definition comes from the 1640 statutes of the Portuguese Inquisition. In declaring who should or should not be admitted into the midst of that administrative, epistemic, and policing body, it is noted that only those with “clean blood, without the race [raça] of Moor, Jew, or peoples newly converted to our Faith” had any place in the Inquisition, and “neither should they be the descendants of people who had any of the aforementioned defects.”1

The second definition comes from Raphael Bluteau’s Vocabulário Portuguez e Latino (1720), the most comprehensive dictionary of the Portuguese language of the 1700s. In this text, raça was defined as: “when speaking of generations [i.e., offspring or heredity], it always takes a bad part [i.e., a negative connotation]. To have Race (without anything else) is worth the same as, having the Race of [a] Moor, or Jew”. Adding, or clarifying in parenthesis that the Misericórdia – an important Catholic, a lay institution that still exists today and which was scattered both throughout Portugal and its empire – “should seek that its servants should not have Race.”2

Exposição Secretariado Nacional Informação, 1948. Lisboa, Portugal. Exposição Catorze Anos de Política do Espírito (Lisboa, 1948). Fotógrafo - Mário Novais. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian

Exposição Secretariado Nacional Informação, 1948. Lisboa, Portugal. Exposição Catorze Anos de Política do Espírito (Lisboa, 1948). Fotógrafo - Mário Novais. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian

According to both definitions, race was something one either had or did not have; there was nothing in between. It signified an undesirable presence, a blemish, and a hereditary taint – or “mácula.” But racelessness also signified a political, social, and religious commitment. To ascend socially to positions of privilege (privilégio) in a military or religious order, it was necessary to attest one’s quality – qualidade. So, when seeking a blood purity attestation (provança de limpeza de sangue), those subjected to the Portuguese bureaucracy of race-making were often attributed impediments on account of the presence of a “defect” – e.g., a “blood defect” (defeito the sangue), or a “mechanical defect,” (defeitomecânico).3 So again, we are moving within an intellectual and ideological field where the material ontology of race is opposed to its absence altogether. In either case, this is a belief system within which not only was religion racialized but constitutive to the very concept of race. In other words, to profess a non-Christian religion made one open to being or becoming racialized. For, as Robert Bartlett noted, in medieval texts (and I would add early modern, too): “while the language of race [in medieval texts] – gens, natio, ‘blood,’ ‘stock,’ etc. – is biological, its medieval reality was almost entirely cultural.”4

Act 2: The Textuality of Skin Color

Skin color was another part of this apparatus of marked bodies and manufactured invisibility. In 1746, one of the physicians to the royal chamber of Portuguese King D. João V, João Machado de Brito, was accused of “possessing the detestable stain [mácula] of the other.”5 In the investigation that ensued, it was clarified that while he had been raised by a New Christian physician with Jewish ancestry, he was not that man’s biological soon. Rather, he had merely been adopted by that converso physician because, as the investigation determined, he was born out of wedlock. His biological father, it turned out, was already married, having two children from that marital union. Declaring the absence of financial means to support his two new sons – João Machado de Brito, the king’s physician as well as his brother – the biological father made arrangements to have the boys raised by said New Christian family.

At first, the identity of the mother was withheld. The reader is laconically informed that she came from a family of some repute, that she lived in a recolhimento, and that she is was a “white,” or “very white woman” (“uma mulher branca,” or “uma mulher muito branca”). Thus, according to the text, withholding the boys’ true filial ties aimed to protect both the mother’s honor, as well as prevent the biological father from the debasing inability to support his children in a manner aligned with his purported qualitas. In the end, João Machado de Brito was declared as having “a noble spirit, and purity of blood,” and hence free from any “defect.”6 Were the opposite true, the king’s physician would not only have lost any rights to his job but also incurred in the hereditarian stain of becoming marked as unfit for royal service. That is, the marking of race – and the concomitant production of the mirage of unmarked whiteness – would have not only been applied to him personally but to all his children and all future family generations, as well. Thus, in early modern Portugal, race constituted a registered mark of explicit hierarchy between humankinds that was not only assumed and acted upon daily but also put on record, thereby producing a biopolitical register of beings with more or less “quality,” or degrees of “defect.” Once such physical, phenotypical, and moral qualities are put on record, and they could not be easily overcome.

Two elements are particularly noteworthy about this case. On the one hand, the insistence on the whiteness of the mother; on the other hand, the paternalistic, patriarchal tone with which the actions of the biological father are presented. Combined, both components present a grid of oppression that attributes agency to white, peninsular, and Christian men with qualitas while placing all other humankinds under their rule. While the presence or possession of raça marked a non-Christian lineage, racelessness conveyed pure, Catholic heredity.

In the end, the king’s physician was deemed to descend from a pure lineage, since his father was not a New Christian and his mother was a “very white woman.” But white must be further elaborated and complicated because the language of skin color transcended mere epidermic pigmentation. Rather, it constituted a metonym articulating the mother’s genealogical extraction, or qualitas, as someone who was Christian, from a good family, and Iberian by birth. The logics of skin color attribution summoned an entire socio-political and confessional imaginary; or, as Max Herring Torres noted: “it follows a language and, given that language is something local, we must take into account that the spatial always follows a social framework.”7 While the logics of raça and limpeza de sangue were first negotiated in Iberia, skin became a vehicle, and color a conduit to articulate colonial proximity or distance to the hierarchies of humankinds encompassed within the Portuguese imperial space.

In early modern Cabo Verde, the valorization of skin color was made manifest in the nomenclature attributed to local, mixed-race elites, or “whites of the land” (brancos da terra).8 In Brazil, conversely, as the desideratum of Amerindian conversion was met with resistance, indigenous peoples became marked with the degrading sign of blackness. “Blacks of the land,” therefore, became the designation deployed by Portuguese agents as indigenous slavery and their respective status and inferior beings demanded a rationale.9 Religion, blood, and the hue of skin color became central to the attribution of defect and the production of race. These classifications of race were produced in Portugal; they were never foreign to it. However, they also traveled and took on specific meanings with shifts in both chronology and geography. Hence, race must be treated as a problem of the Portuguese past and present.

The language of “defect” also calls our attention to the centrality of disability to race-making – and the importance of intersectional approaches. Hierarchies of being were enforced through multiple mechanisms. “Defect” marked bodies with the sign of deviance. And here, the attribution of reason is critical. Jewish “heresy,” African “barbarism,” Amerindian “heathenism” all conveyed a racialized indulgence in the sins of unreason – i.e., failure to recognize Christianity as “the” truth that spoke to nature and the ranking of humankinds. Those who could not reason necessitated tutelage – their bodies being enslaved to their passions. Thus, slavery constituted not only a means of disciplining and molding inferior kinds of humanity but a method of saving their immortal souls while expending the mortal, corruptible, physical body through redemptive suffering. Or, as the chronicler Zurara noted: “for though their bodies were brought into subjection, that was a small matter in comparison with their souls, which would now possess true freedom forevermore.”10

Act 3 – (Un)Archiving Race: Classification and the Politics of Search Words

The record was not only brief but also misspelled. Where it should have stated “suicídio” (suicide), I found the word “suídio,” which does not exist in Portuguese. I did not know this at the time, and as someone who works with the eighteenth-century archives with many arbitrary spellings, I requested the items with interest and curiosity. As I sat down to read, in the Portuguese National Archives (Torre do Tombo), I realized what had happened. The first thing that struck me was its brevity. As I made my way through the laconic text, I learned two things. One, that the text relayed the case of an enslaved man, José from Mina, who took his own life; the second that the record was misspelled. I copied and transcribed the case – not knowing if I would ever speak about José to anyone. At the return desk, I informed the staff of the error in the record, noting it should be correct. It is still there today.

This case illustrates the difficulty of recovering Black lives in the archives. Ubiquitously interstitial, Black, indigenous, Romani subjects are both everywhere and nowhere. Unindexed by our taxonomies of classification, they are actively excised from our collective memory. (Perhaps, that is because we do not want to remember.) The way they do not easily show up in search words or database parameters only highlights the fragmentary nature of the record – something that our disciplinary canons and methodologies centered on causality and the linearity of biographical or chronological reconstitution both abhor and refuse. Here, blackness poses a methodological challenge: if knowledge-making parameters reject the fragmentary nature of the record, what to do when fragments are all that was bequeathed?

But the conundrum deepens. Without categories – be it Black, pardo, or any other – race will remain occluded from our sights and subject to haphazard requests for unmarked documents. But I suspect there is something deliberate here, too. For as long as we do not have to think about how enslaved people were called “peças,” how they were routinely brutalized, their bodies seized and marked with the imprimatur of the Portuguese sovereign, and how their children were called “crias” – a term normally applied only to the offspring of animals – as long as we do not have to think or know that, then we are free to insist on the mythologies of benign rule and racial harmony.

Padrão dos Descobrimentos, Lisboa, Portugal. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian

Padrão dos Descobrimentos, Lisboa, Portugal. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian

This phenomenon reached an epitome in 2017, in Gorée, present-day Senegal. In a state visit, the Portuguese president lauded the 1761 abolition law as: “when we abolished slavery in Portugal […] that decision of Portuguese political power provided recognition of the dignity of man, and of the respect for a status correspondent to that respect.”11 However, if we return to the archive, we see that this law did not aim to end slavery, but to focus it on the South Atlantic, thus maintaining a steady supply of enslaved people to Brazilian mines and plantations. At the same time, we continue to unsee Black life in sources where we cannot even imagine its mark.12 This is the case of the police records (Intendência Geral da Polícia). When looking at some cases for the year 1780, for example, I “found” two enslaved, Black men who had heard about the law President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa fallaciously lauded – as well as the subsequent 1773 law. They believed that by fleeing Brazil and entering Portugal, they would become free. However, according to the police record, they were not only imprisoned but were awaiting deportation from Lisbon back to Rio de Janeiro.

They had no right to freedom; the law built to promote their enslavement kept working.

These non-indexed, non-searchable experiences blemish the mythological patina of exceptionalism. Cynically, this is why, I believe, investing in the upkeep of archives is so neglected in Portuguese public debates about history. The “Age of Discoveries,” importantly, is not just a problematic historical myth, but an industry. How unsavory and hard to commodify would the “discoveries” be, if we reckoned with race and were willing to archive it as such?

Act 4: Postcolonial Traumatic Disorder

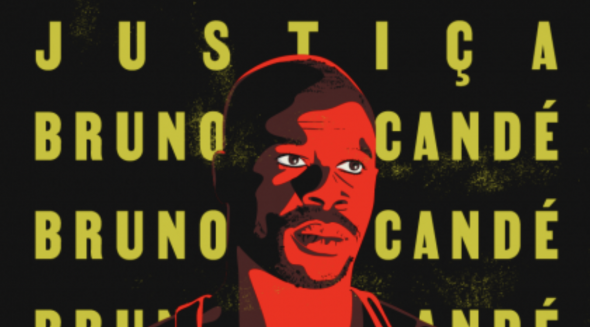

“Tenho armas do colonies em casa e vou-te matar!,” was the threat made by Bruno Candé’s murderer, a 76-year-old former nurse’s assistant and a veteran of the Portuguese Colonial War. According to witnesses, these words were accompanied by a recurring deluge of racial slurs that became all too familiar for Candé, a 39-year-old Black man and Portuguese citizen. On July 25th, 2020, the harassment escalated, reaching a point of no return. The murderer aimed four point-blank bullets at Candé’s neck and chest as he screamed: “volta para a senzala.”13 The crime happened in broad daylight, at a café in the outskirts of Lisbon – where Candé frequently sat with his dog. His death was instant and on the spot.

The murderer’s assertions recalled and rendered visible Portugal’s long history of colonial violence. Despite the enduring silence on the murder and the denialism that ensued both in the media and through a police spokesperson, the reproduction of plantation brutality lay, unequivocally in the murderer’s words and deeds. While the past of racist violence and colonial conflict was silenced and rendered invisible, in contemporary Portugal, it was neither foregone nor resolved. Rather, it persists; sanitized, and unreckoned with. Archival voids and racist denialism endure and are made manifest in the selective amnesia that systematically excludes Black lives and embodiment from the historical and citizen imaginary; carefully excised both from past and present.

In Portugal, the specters of coloniality soak the fabric of everyday life. From a very young age, all of us grew up surrounded by, and inured to, the aestheticized public performance of empire. And while empire was ubiquitous to all our cities and monuments, privately, all of us who grew up racialized as white, we were taught to normalize the intimate reality of trauma, silence, and the nostalgia soaking most personal stories about life in Africa – disconnecting always that existence from the presence of race or the practice of racism. These two versions of the past – a public and a private – cohabitated under the same roof, side by side, and in very tight quarters. Depictions of idyllic life in Africa, along with the traumas and disabilities inflicted by the war, all continue to enforce a pact of silence about colonialism and the racist animus undergirding both ideologies and structures of sentiment.

The racial scripts, to cite Natalia Molina, remain ossified still in the modes of thought, images, and imaginaries about whose bodies are perceived as agential knowers, capable of sovereign self-government versus those perceived as pathological, less reasoned, and thus father from prototypical humanity. The tacit mirage of white, upper class, able-bodied masculinity, to provide an account fuller than Frankenberg’s, continues to pathologize its others as deviant. By questioning the implicit image of the prototypical human, we may uncover how its unreasoned others are construed; how they demand the paternalism of vicarious salvation. And, despite the purported universality of Catholic and secular republican humanity, how disabled, racialized, queer, or feminine existence is not only pathologized but subject to state regulation, unable to exercise autonomy whilst becoming a contested object of jurisprudence. The way the Portuguese state denied citizenship to Black subjects through the law, abortion rights to women, marriage, and the right to adopt to the LGBTQ community and continues to deny fundamental forms of access to its disabled citizens continues to recapitulate the violent imprimatur of coloniality.

Today, we are learning that invisibility can shun and silence but cannot extinguish. And yes, colonialism can be unlearned; but to do so, it must first be confronted. Colonial amnesia is a political disease – and one for which we have yet to find a cure. Unlike the words uttered by Bruno Candé’s murderer, there are no more senzalas to return to. But, aligned with the theme of reckoning that brought us here today, in order to unlearn colonialism and effectively seeks to decolonize ouselves as well as the world around us, the past must be confronted. One way to start, would entail acknowledging the intersectionality of race-making and forge a vision of collective life not ruled by marked hierarchies.

Major sections of this paper were read during the event “Portugal, Race, And Memory: A Conversation, A Reckoning” organized by Mira Assaf Kafantaris at The Ohio State University on March, 24, 2021. The author wishes to thank all her co-panelists for the generous and generative conversation.

This event was moderated by Professor Lisa Voigt (Spanish and Portuguese, The Ohio State University). Presenters included Pedro Schacht Pereira (Spanish and Portuguese, The Ohio State University), Patrícia Martins Marcos (History and Science Studies, University of California San Diego), Kathryn Vomero Santos (English, Trinity University), and Mira Assaf Kafantaris (English, The Ohio State University).

- 1. Apenas aqueles com “sangue limpo, sem raça de Mouro, Judeu, ou gente novamente convertida a nossa Fé, e sem fama em contrário: que não tenham incorrido em alguma infâmia pública de feito ou de direito, nem forem presos, ou penitenciados pela inquisição, nem sejam descendentes de pessoas que tiveram algum dos defeitos sobreditos, serão de boa vida e costumes, capazes para se lhe encarregar qualquer negócio.” (Título 1, Art. 2). Emphasis added.

- 2. “Raça Fallando em gerações, se toma sempre em mà parte. Ter Raça (sem mais nada) val o mesmo, que ter Raça de Mouro, ou Judeo (Procurarseha, que os servidores da Misericórdia não tenhão Raça. Compromisso da Misericórdia, pag. 26 vers.)” Raphael Bluteau, Vocabulário Portuguez e Latino, 1720, p. 86. Emphasis added.

- 3. The former signified one descended from a lineage of non-Christians, while the second signified a hereditary connection to a family that had performed manual labor in the past, and therefore, a family which lacked “quality.” While the former could only be lifted or erased by the Pope, the Portuguese monarch alone could lift all evidence of mechanical defect.

- 4. Robert Bartlett, The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization, and Cultural Change, 950-1350 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 197.

- 5. “[…] mas com a detestável mácula do outro.” João Thomaz Negreiros, Allegação Jurídica Que a Favor do Doutor João Machado… (Lisboa: Na Officina de Miguel Rodrigues, 1746), 1.

- 6. “o nobre espírito, e pureza de sangue,” Negreiros, Allegação Jurídica, 2.

- 7. Max S. Hering Torres, “Color, pureza, raza: la calidad de los sujetos coloniales” La cuestión colonial. Heraclio Bonilla Ed. (Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2011), 452.

- 8. João de Figueirôa-Rego e Fernanda Olival, “Cor da pele, distinções e cargos: Portugal e os espaços atlânticos portugueses (séculos XVI e XVIII),” Tempo, 2011, vol.16, n.30, 115-145.

- 9. John M. Monteiro, Indian Slavery, Settler Society, and the Portuguese Colonial Enterprise in South America, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018). Originally, Negros da Terra: Índios e Bandeirantes nas Origens de São Paulo, (São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1994).

- 10. Gomes Eanes de Zurara, The Chronicle of the Conquest of Guinea, edited and translated by Charles Raymond Beazley and Edgar Prestage, 2 vols. (London: Hakluyt Society, 1896-1899), 51.

- 11. “Quando nós abolimos a escravatura em Portugal, pela mão do Marquês de Pombal, em 1761 - e depois alargámos essa abolição mais tarde, no século XIX, demasiado tarde -, essa decisão do poder político português foi um reconhecimento da dignidade do homem, do respeito por um estatuto correspondente a essa dignidade”. Emphasis added. “Portugal reconheceu injustiça da escravatura quando a aboliu em 1761, diz Marcelo,” Público, 13 de Abril de 2017. https://www.publico.pt/2017/04/13/politica/noticia/portugal-reconheceu-i...

- 12. Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, PT-TT-LO-003-6-040 https://digitarq.arquivos.pt/viewer?id=4662332

- 13. In Brazil, senzala means slave quarters, while in Portuguese Africa, it designated, more broadly, a neighborhood where only Black population resided.