Sorcery Trials, Cultural Relativism and Local Hegemonies

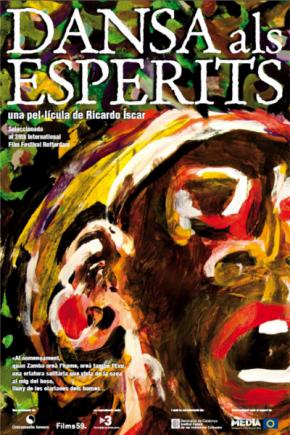

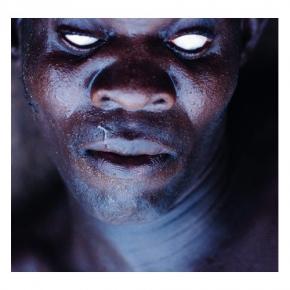

Images from the movie Dansa als Esperits, from Ricardo Íscar.

Stating that sorcery exists in Mozambique is a mere declaration of an obvious and recurring fact. People may use it in order to obtain active results or to protect oneself from undesirable events, in the pursuance of legitimate or illegitimate, beneficial or malevolent goals. The effectiveness of this practice is, nonetheless, an issue that tends to divide readers between outspoken scepticism, attitudes of plausible doubt, complex speeches about its symbolic efficacy, and a somewhat apprehensive fear or agreement.1

However, my interest in this chapter does not focus in the real practice of sorcery. My purpose is to analyse something that invariably gives way to serious and tragic consequences – whether or not this affects the real practitioners of such crafts - and that interlinks with the issue of ‘legal pluralism’, the subject-matter of this book. I am referring to the accusations made against individuals, claiming that they practice or order spells, as well as the trials of such accusations.

I will begin by stressing that sorcery is an essential element of the ‘domestication of uncertainty’ system that is dominant in Mozambique, and consequently of the social efforts to give a meaning to, and try to overcome, the unexpected or aleatory events. However, as I will subsequently discuss, sorcery allegations are also an important tool of social control used against defined victims. They tend to reproduce and reinforce the existing relationships of inequality and domination within society, more often than not in a particularly violent manner.

In this chapter I provide an account of such violence, and of the dynamics of prosecution and trial by describing the typical and expected course of a prosecution, the production of evidence and trial procedures, and by examining two specific cases. The reader will then be able to identify that sorcery trials are seen as an institutionalised form of justice by those concerned, that prosecution and trial usually interact with other non-state figures and institutions that are also considered ’justice providers’, and that the rights of defendants are often breached in the course of procedure.

I argue that the acceptance and legitimacy of sorcery trials (and, ultimately, of the overall idea of legal pluralism) are based on the projection of ‘cultural relativism’ principles upon individual and collective rights. Hence, I will discuss the harmful effects of such employment and its abusive nature in scientific, ethical and political terms. In doing so I will consider an alternative to the common, and misleading, dichotomous dilemma between, on the one hand, accepting ‘cultural’ rules as an obstacle to the rights of certain groups or, on the other hand, imposing compliance with general and abstract rules, regardless of the meanings that the people assign to the practices in question. I rather suggest that, whenever ‘cultural’ practices and ‘human’ rights do oppose, the primacy should be given to the perspective and will of those individuals and groups that are dominated in such cases.

Lastly, I will suggest for the reader’s consideration a set of questions of a scientific, ethical and political nature which, at this point in time, should not be concealed when discussing legal pluralities. These questions will be based on the view that sorcery trials are not an unusual and extreme ‘deviation’ in the practical application of legal pluralism, but rather an expression of this concept, in which the inherent harmful effects are easier to perceive.

Sorcery and the domestication of uncertainty

The first aspect to take into account when studying the social role of sorcery in Mozambique is that sorcery is not an isolated belief, but rather a vital part of a wider (and largely collective) system of interpretation of, and action on, misfortune and other uncertain events. This fact is far from irrelevant. As George Murdock (1945) emphasised last century, in a statement that has not been disputed, divination systems exist in every culture known to history or ethnography. However, divination systems are not isolated from wider conceptual frameworks. Their rationale is based on interpretation systems intended to give meaning to contingency and to guide human intervention into the uncertain and unfamiliar. Since such interpretation systems also exist in every culture, it is plausible that they meet a human need of a universal nature, thereby demonstrating the cross-cultural importance of the human struggle against the humiliation of uncertainty, against the lack of meaning and against human dependency on what appears uncertain and random.

The systems that result from such human struggle may originate from different principles. When investigating the logical possibilities of understanding uncertainty and threat, we soon realise that the possible alternatives may vary between two extremes: on one side, the absolute assumption that aleatoriness is ‘existent’ and is the principle underlying uncertain events, thereby acknowledging contingency as part of the process; on the other side, the assumption that uncertain events are fully determined by extra-human logics or entities, such as divine will, fate or the mechanistic laws of a clock-like universe. Between these two extremes there is a continuum of conceptual possibilities, which share the attempt to ascribe meaning and causality to uncertainty and aleatoriness, which enables the latter to be perceived as cognoscible, regulated or even dominated by humans. This represents what I describe as forms of “domestication of uncertainty” (see Granjo 2004).

It is quite common for different ‘uncertainty domestication’ systems to co-exist within the same society. Depending on the specificities of each occasion, people may decide to use only one of such different systems, to mix them in a syncretic way, to apply them alternately to various aspects of reality (Granjo 2008), or to use them complementarily, even if their rationales seem to be contradictory.

Mozambique is no exception in this regard. Here too, there is a co-existence of materialistic, religious, magical, technological, and spiritualistic systems of reasoning and interpretation. We may nevertheless affirm that there is one particular ‘uncertainty domestication’ system in use in most of the country which, albeit co-existing with other systems, prevails in the interpretation of events that disrupt expected normality. This is because the theory is that happenstance and coincidence do not exist. Thus, events that strongly harm (or benefit) someone require the existence of underlying causes, particularly if such events are recurrent. These underlying causes do not replace and are not opposed to material causality. Indeed, they do not represent an attempt to explain how a specific dangerous event occurs, but rather explain why such an event has harmed the specific person in question. According to this point of view, the world is full of material and natural threats, ruled by material causes; however, although undesired events follow material causality relations, they may only harm a specific person due to social causes which make both victim and the source of danger coincide in time and space. These social causes need to be identified when misfortune strikes, in order to explain the misfortune and to prevent its recurrence, in a similar or a more serious form.

In such an event, however, the first suggestion is to confirm the victim’s possible negligence or lack of skill. The reason for what happened to the victim resides in his own inadequacy in situations where: the victim was unaware of the danger or was unfamiliar with the right way of performing some action; the victim lacked the experience to perform the action, or; when the victim did not used to take the necessary precautions. Other social causes, of spiritual or magical nature, are sought for only if the victim was competent and careful, but was nonetheless hit or harmed by the undesirable event, or if, exceptionally, he/she was not as careful as he/she normally would be.2

One of the likely causes in such situations is the suspension of protection by the victim’s ancestors. Since the latter maintain a relationship with their descendants similar to that of elder relatives, it is their duty to guide them, protect them and keep them away from danger, which they probably did not do in this event. If that happened, it was not a punishment but rather the result of the constraints that the ancestors are facing: since they are the spiritual remains of the person they once were while living, they lost some human capabilities, among which the ability to communicate directly with the living. As such, the only way the ancestors have to express that they are displeased with something and that they need to transmit it to their descendants is by allowing undesirable events to happen to the later, in order to alert them to seek communication, through divination or the trance of an expert. The next step for the living should be to try to find out why the ancestors are dissatisfied and to find out what can be done to remedy the causes of such dissatisfaction or, at least, to appease them.

The other likely cause or reason could be sorcery. Mostly attributed to envy or other objectives considered negative, such as greed and selfishness, sorcery is normally considered to affect the reality trough means which are inverse to the actions of ancestors when they are trying to protect their descendents. In fact, although it is believed that powerful spells may directly manipulate material factors and create their own dangers, such diagnoses are relatively rare, and largely limited to exceptionally tense situations of social strain. What is common is for sorcery to act upon people or beings, by attracting them to danger, by distracting them from the hazards existence and imminence, by influencing their behaviour, or even by hiding from them some aspects of reality or creating in them the illusion of imaginary situations.3

However, regardless of the differences in its operation and targets, sorcery plays a crucial role in an ‘uncertainty domestication’ system, which is paralleled in other regions of Africa.4 Yet, unlike common understandings, it is a system which does not restrain people to the principles it advances, forcing them toward a predestined or irreversible future. The acknowledgement of social complexity, including the interaction of individual and collective volitions and actions – from the living and from the dead, of a material, spiritual or magical nature – turns sorcery and each particular spell into a factor that interacts with many others, in a framework of multiple attempts to mould an uncertain future (Granjo 2008a).

Sorcery provides, therefore, a means to give logic to uncertainty and aleatoriness by making them explainable, and by enabling the reintegration of misfortune as both a cognoscible thing and as a result of human action and, as such, liable to manipulation by such action. In this way, sorcery – along with the other aforementioned causal relations - is a way of understanding something that otherwise would not make any sense. It is also a way of acting on reality, by provoking or by avoiding the undesirable events.

Yet, sorcery and particularly the accusations of sorcery practice (which are the focus of this discussion) do not play only this role of domesticating uncertainty.

Defendant(s) and Social Control

To accuse someone of practicing or ordering spells is not just an attempt to explain misfortune, or to incorporate into normality something that is deemed abnormal. Accusing someone of sorcery (or even the implicit threat of such an accusation) is also a powerful tool of social control, if not one of the pursuit of economic and political strategies.

Again, this is not exclusive to Mozambique. Works such as Schism and Continuity, by Victor Turner (1957), or Witchcraft, Power and Politics, by Isac Niehaus (2001), expressively demonstrate this in quite different historical and geographical contexts. Nevertheless, one should bear in mind that such potential for social control and collective manipulation may take on distinctive meanings and have diverse consequences.

There are also important regional disparities within Mozambique. In his book Kupilikula, Harry West (2009) draws a scenario in the Mueda plateau where sorcery occurs in an invisible world that interacts with ours, and into which infamous sorcerers project their spirit in order to carry out their evil doings. Such doings may only be counteracted or reversed by a similar projection of righteous sorcerers to act on whatever was motivated by the infamous ones.

Such action, through a spiritual, shamanic voyage into an invisible world detached from ours, is dissimilar to the prevailing views in the southern and central regions of the country. Here, the active spiritual force is not the living person’s, but rather the dead spirits’ that possess him or that he is able to dominate and put to his service.5 It is the spirits who act on the perceptible reality in forms we term magical. They do not do it in an invisible world, although they are invisible, but in ours, which they also inhabit.

This formal difference, identifiable in Mueda, does not prevent moral references of sorcery practices (and accusations) from being similar to those in the rest of the country, albeit perhaps more explicit in their logical consequences. Thus, any person more powerful or richer than those in the vicinity is, until proof to the contrary is provided, a sorcerer, either because he/she needed magical support to achieve that exceptional status or because his/her status requires protection to be given to his/her subordinates. The latter is only possible if one knows how to fight against malevolent sorcerers by resorting to benevolent uses of sorcery.

And yet, this assertion of the ambiguous nature of power finds another expression here, which is one of a more general character. Malevolent sorcerers are selfish and use their power and knowledge exclusively for their personal benefit. As such, the one who enjoys the advantages of power without fulfilling the obligations of protection such power commands, or the one who becomes wealthy without sharing part of his wealth with those he leads, by ‘eating alone’, proves, with such behaviour, to be a malevolent sorcerer. This is what led, for instance, to the lynching of several persons accused of owning, or transforming themselves into, the lions that terrorised the population of Muidumbe in 2002 and 2003. The lynched people were relatively rich and powerful and, as pointed out by Harry West (2008) and Paolo Israel (2009), the case was an expression of political criticism of the post-socialist appropriation of wealth and power, to the detriment and with disregard of the ordinary population.

The same was observed, in a more subtle way, after the popular uprising of February 5th 2008 in Maputo. It was said at the time that ‘the people came out of the bottle’. This eloquent expression, which was rapidly disseminated from the outskirts to the centre of the city, also translated the political and socio-economic criticism into the language of sorcery by readdressing the belief that many women illegitimately dominate their husbands, making them apathetic and abusing them through a spell that ‘puts them inside the bottle’. This spell can only be broken by a stronger counter-spell, which in this case was the uprising (Granjo 2008b; Granjo 2010). However, the accusation of sorcery is ever-present in daily life in events much less spectacular than these larger public convulsions.

As mentioned above, unexpected misfortunes, and particularly an unusual sequence of disease and death, require a logical explanation which provides them a sense and that allow people to control and overcome such events, and restore normality. Sorcery is but one of many possible explanations on such occasions. However, the spell is a possibility that can easily gather consensus, including about the probable instigator. This can for instance occur in the absence of obvious social causes on the victim’s side, or on the side of someone close to the victim - that could give reason to suspension of protection by the ancestors. And it can occur in the presence of social conflicts and tensions or behaviours considered strange or envious, which is always very likely.

Moreover, considering that the suspicion of the practice of sorcery is justified by specific types of relations and social status, the resulting accusations also tend to be typified. Agreeing with the findings of the study led by Carlos Serra (2009) on the lynching of people accused of sorcery in rural areas, my data also indicate that these accusations tend to be focused on specific, socially weakened individuals. This typicality is strongly gendered. Indeed, although the most feared and famous sorcerers - not the most confronted or challenged ones - are usually men, the overwhelming majority of people accused of sorcery are women.

Exceptions usually occur when a specific man has particularly serious conflicts with the affected group, shows exaggerated and hasty micro-political ambitions, or possesses a substantial amount of property at an age that is considered too high for him not to have begun to redistribute the property among his heirs. Another situation that involves men, and where the accusation is socially equivalent to that of sorcery (although strictly speaking it is not), is when a woman has a complicated sexual relationship with her husband, expressed by violent or ‘mad’ behaviour. These cases usually entail the suspicion that the woman was offered in marriage to a spirit by her father, whether as compensation for a family debt to the latter or as a result of a pact with the objective of becoming wealthy.

In this way, the accusation of men – accounting for the minority of instances, as mentioned above - tends to be linked to the resolution of family conflicts and to the sanctioning of greedy political and economic behaviour. Vulnerability increases with age.

However, not just any woman is accused of sorcery either, despite the fact that gender vulnerability weakens them.

The most common views on the effectiveness of sorcery are associated with proximity. In other words, only the most powerful experts will be able to cast a spell from remote locations, whereas the average sorcerer has to be close to the victim to do so. Whether or not this image of proximity is originally the reason or the ideological formalisation of what I am going to say next, the practical outcome is that the sorcerer should be physically close to the victim, but at the same time keep a social or behavioural distance from the victim so as to give reason for the evildoing and the desire to do it.

Therefore, the kin resulting from marriage have a privileged structural position as primary suspects, particularly women living with the husband’s family. If these women demonstrate behaviour deemed undesirable they will automatically become suspects. This could for instance, include situations where the women are quarrelsome or defiant of their mother-in-law and sisters-in-law, insufficiently respectful of or zealous toward their husbands and his elders, or envious of the assets or children of other women.

Widows are also in a weak position with regard to possible accusation, particularly if they own locally significant assets and started to behave in a more independent way, after widowing. These women are affected by a convergence of factors, including limited defence capacity, an image of economic greed, a life experience that might have given them access to magic secrets, the economic expectations of the possible beneficiaries of the accusation, and gender power tensions. These are factors which, in turn, will add to the already existing and common suspicion about the widow’s likely responsibility for her husband’s death, which may be revived and work as complementary ‘evidence’ in the presence of new suspicions.

Furthermore, behaviours that diverge from the local role models of femininity and gender power may become sufficient reason for suspicion and consequent accusation.6 There are degrees to this, of course, which are certainly not immune to the particular backgrounds and dynamics of gender roles negotiation, which take place in each case and context.

However, it does not necessarily have to be “a very strong woman that can beat up any man”, according to the newspapers descriptions of a woman who was impaled in 2008 during a surge of lynching in Chimoio, in order to gather consensus about her condition of being a sorcerer. As we will see below, suspicion of sorcery could simply be the result of a woman standing up against her husband, after a long period of her being the victim of domestic violence.

In a very specific case, a woman could be accused not because of her own characteristics but simply because of her husband’s behaviour. Even in urban areas, both in popular and more elitist circles, when a man ‘obeys’ his wife or has atypical habits - such as rending most of his salary at home, not going out with friends, not showing interest in other women, cooking or openly doing house chores - this tends to be considered by his relatives and neighbours as against his nature or choice, and as the result of a spell cast or ordered by his wife to illegitimately keep him under her grip. And although the accusation of such a spell has less serious physical consequences than others, it nevertheless entails counter-spell actions and divorce (Granjo 2011).

So, although an accusation of sorcery could be based on different sets of leads, liable to give rise to social consensus about their validity, it tends to be marked by two characteristics: (1) a focus on socially weakened figures with limited defence capacity, mostly women and elderly women, and; (2) a justification based on the ascription to such figures of behaviours and actions which are not compliant with the role models imposed by the power relations that are in force locally.

As such, sorcery accusations are powerful tools of social control that punish deviations to the dominant norms which govern behaviour and power relations, and coerce compliance, either through the accusation itself or through the threat of accusation at the first occurrence of misfortune.

However, we should also note - partly underlining what was mentioned above - that there are special instances where the practice of sorcery is tolerated or even considered legitimate, even if made public openly and practised by women. A good example of this is the case of a gardener of a large company’s general-manager who, to the surprise of the later, took for a fact that his mother had put a spell on him, which made him sad but not angry. It turned out that the man was the genealogic successor to a ‘traditional’ chiefdom, but had refused to take up the position, because he had a stable and relatively well-paid job. Besides, all the money he was able to save was invested in the construction of a new home, regardless of the alleged financial difficulties of his mother, siblings and uncles. He was, therefore, in a relatively serious situation of double default before his family, the community of origin and his ancestors. This was a situation that justified or excused his mother’s use of such violent tools of coercion.

Therefore, sorcery may be implicitly authorised or even respected by the community, as long as it is not concealed and it adopts a social control and coercion role. This is used to compel individuals to assume a more socially desirable conduct. In other words, sorcery is accepted as long as it fulfils the social role that is expected, usually, to be fulfilled by sorcery accusations.

How sorcery is judged and how people get accused

This potential ambiguity concerning the sorcery practices acceptance is also valid – at least in abstract terms – in what concerns the dynamics and possible outcomes of sorcery accusations. Indeed, an accusation of sorcery, even if confessed by the accused or deemed proven by the accusers, does not necessarily lead to punishment and marginalisation.

The system of ‘uncertainty domestication’ and the local phenomenology of possession also generate an opportunity to enable and facilitate social reintegration. As such, the accused should acknowledge his/her fault and agree to have been possessed by an abusive spirit that forced him/her to act and behave against his/her own will. Moreover, the allegation needs to be consensually accepted by the accusers and to be confirmed by experts.

Such confessions do not have to result from a hoax to be rational, according to anthropological criteria. After all, if it is socially consensual that people may commit an act under possession without being aware of it, and if everyone - including the experts in the matter - is sure that a specific person committed an evildoing, thus it becomes plausible to the accused that he/she might have committed that act without knowing it.7

However, if a person commits an act while he/she is being dominated by a spirit, the responsibility rests on a symbiotic entity – formed by the possessed person and the possessing spirit – and as such the person is also responsible, albeit strictly speaking not guilty. More importantly, as soon as the spirit is removed from the body and prevented from returning, by means of arduous but innocuous ritualistic procedures (Granjo 2007), the person returns to what he/she once was and will no longer be a danger. Therefore, nothing prevents his/her full social reintegration.

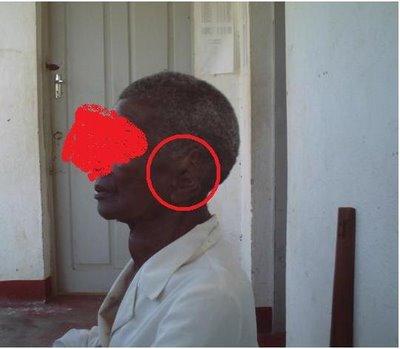

acusada de feitiçaria, mão decepada, foto de Carlos Serra

acusada de feitiçaria, mão decepada, foto de Carlos Serra

However, the exceptional nature of this outcome - which has always been told to me along the lines of ‘as it once happened…’ - is a further indication that sorcery accusations do not have the explanation and justification of misfortune as the sole objective. They are, also, essentially motivated by a quest for social control and punishment.

Indeed, the creation of scapegoats and the collective pressure leading to economic exploitation, banishment, mutilation, insanity, and even death are much more frequent. The level of consensus established about the individual blame, his/her guilt, and the benefit of destroying him/her as a social being, or even as a living being, is crucial to the outcome. Often, such accusations end up by not being subject to any formal trial, whether performed by non-state political entities or by healers’ associations. Particularly in more remote areas, away from all figures of state authority, a confirmation of the collective suspicion by divination by an expert is usually enough to expel, injure or kill the accused – in principle, but not necessarily, with prior consent from a ‘traditional authority’.

In areas with higher population density or in cities, however, the achievement and analysis of evidence and the promulgation of the punishment by some political authority tend to be formalized. Usually, and unless the accused confesses immediately, the first divination that confirms the suspicions by the accusers has to be confirmed by a group of experts appointed by the respective professional association8 in a previously arranged meeting that takes place within a tense and solemn ambiance. Although the details of the case - including possible material evidence of sorcery - are explained at length by the complainants, and possibly challenged on behalf of the defendant, the formal means of proof is joint divination by the appointed experts. In the southern region of the country this is done by casting the tinhlolo (Granjo 2007a),9 whose reading, allowing for different lines of interpretation, is expectedly influenced by the previous allegations.

However, even if ‘sorcery judges’ have the authority and the competences - that are acknowledged by the parties by their mere attendance at the trial - to confirm or infer the guilt of the accused, the only tools the judges have to extract a confession and/or a settlement agreement are their rhetoric and performance skills, associated with the fear and respect they evoke. Sometimes such tools are not enough and it is necessary to convene more restricted sessions that take place in the bush, which I will describe below.

The path driving a person towards a sorcery trial can, however, be more complex and unexpected. For example, it can go through a Community Court (Tribunal Comunitário) that deliberates to be incompetent to judge a sorcery case or a suspicion of sorcery in a case where this was not expected, referring the matter to a sorcery court. This is what happens in the first example that I will account for. I will do so in the most neutral and unbiased manner that I can muster so as to limit the impact on the reader and the legal consequences of such a description.10

As mentioned, the case starts at a Community Court. The complainant is a married woman applying for divorce due to repeated aggression by her husband over the years they have spent together. The last time she was beaten she was able to run away and seek refuge with her family of origin, whence she filed the claim. However, the detailed description of the events showed that, on this last occasion, the woman stood up to the husband and hit him on the head with a frying pan in order to escape. The mood changed instantly as soon as this was disclosed at the trial. The ‘judge’ was astonished, and both he and the people representing the husband set about questioning whether such an unusual reaction from the woman would not be explainable solely by the fact that she had become a sorcerer. The judge, feeling incompetent to try such matters, immediately summoned a ‘Sorcery Court’ against the woman who arrived there as a complainant.

acusado de feitiçaria, orelha decepada, foto de Carlos Serra

acusado de feitiçaria, orelha decepada, foto de Carlos Serra

The new trial, albeit an ad hoc one, started in accordance with the usual procedures mentioned earlier. However, and given that the woman insisted on not admitting her guilt, one of the judges gave her a mirror and asked her what she saw in it. As expected, the woman said she saw her image reflected in it. ‘That is the proof ‘, someone answered her, adding that: ‘This is a magical mirror and only shows sorcerers!’ I do not know what happened to this woman, who continued to deny the accusation, though such an extraordinary piece of evidence convinced most of those present.

The next case I am going to present illustrates, however, a usual development when someone consensually deemed guilty insists on denying the accusations of sorcery against them. The new trial does not take place in an urban or peri-urban area. It happens in the middle of the bush in an isolated place that can only be reached on foot, but preferably close to a crossroad. Furthermore, it is no longer, strictly speaking, a public trial. Although some representatives of the parties are present, this procedure is strictly confidential, with the exception of the final outcome.

In this case, the defendant was also a woman, who appeared to be around 50 years old. Although the procedures went over a new and relatively long session of questions and allegations, it was clear that the defendant’s guilt - reconfirmed by casting the tinhlolo - was taken as a given. Therefore, the issue was not about investigating such guilt, or even proving it, but rather about forcing the defendant to confess.

Following a long phase of reprimands and attempts at convincing her, combined with threats, a sequence of tests were prompted whereby the defendant, under constant pressure, had to find objects, animals or plants, or had to give evidence of confidence and courage to prove her innocence. Some insurmounted tests (or virtually impossible to pass, like finding the uncommon pangolin), increased her insecurity and emotional tension to a state of progressive physical exhaustion. Although exhausted and disoriented after many hours of physical and psychological coercion, the woman kept on denying the accusation and was then administered mondzo. This is a diluted liquid of plant origin that induces a state of absent-mindedness and lack of control. The person that drinks the liquid ends up by confessing everything he/she did wrong - whether sorcery or not - in a conversation with an imaginary person. Nevertheless, - and as espionage stories go regarding the ‘truth serum’ - it is assumed that some people are able to control its effects, and never confess. Such an exceptional possibility may result in the administration of a new measure of the product, which is likely to result in an overdose that makes the temporary effect of absent-mindedness and hallucination become permanent – like it happened to this woman.

Lastly, cases of extremely high social tension and unanimity about the guilt of the accused person may end up with a submission of the accused to an ordeal where a toxic product is administered that supposedly is harmless to the innocent, but should kill the guilty or drive him/her mad.

Good intentions, cultural relativism and rights

I suppose cases such as the ones I accounted for above will not leave the reader indifferent, even if the reader is the greatest enthusiastic supporter of ‘legal pluralism’ or someone, like me, who has learned to think about local divination and healing practices in his own terms and within his own conceptual framework. Yet, the reason these cases require our review is not limited to the need to look at the means of evidence used, the degree of coercion and violence, or even the violation of rights deemed fundamental and safeguarded by the state, beginning with the abolishment of the death penalty.

All these questions are unavoidable. But, as we are in the presence of something that is intended and accepted by the parties involved as a specialised method of administering justice, which co-exists in coordination with other entities that employ ‘legal pluralism’, the concerns that make us question this judging system should lead us, as well, to questioning the legitimating principles of legal pluralism.

While risking generalising and simplifying, one may say that the forms of reasoning which try to legitimate legal pluralism - and their respective motivations and employed principles - pursue two main trends. On the one hand, they are based on a practical concern: the state’s capacity to provide justice is and will be scarce. This could be avoided by mobilising and recognizing locally entitled conflict resolution entities,11 acting in accordance with locally accepted principles. On the other hand, they are based on a concern for ideological equity: it is assumed that there is a ‘Western’ hegemony,12 which enforces institutional frameworks, principles and notions of rights that are alien to, and disrespectful of, all other cultures. Therefore, for such other cultures, resolving conflicts and administering justice in conformity with their own principles and means would represent factors of emancipation and of fairer social functioning. This second trend, mostly developed within the academic context, finds its theoretical and moral legitimacy in the respected anthropological principle of cultural relativism.

I believe the case of sorcery accusations and trials is an excellent starting point (as could be gender, age or any other aspect of social inequality whose distinction is culturally encoded) for assessing the extent to which the application of the concept of cultural relativism onto people’s rights is problematic and potentially perverse.

In truth, however, the concept is already tricky in abstract and theoretical terms, even before we confront it to empirical cases. This is the result of the fact that the beloved assumptions of cultural relativism - according to which the various cultures are not superior to each other and each culture should be understood in its own terms – are not in this case applied to strictly cultural phenomena, but rather to political phenomena.

We can certainly state that, in light of the far-reaching concepts of ‘culture’, which I subscribe to, the ‘political’ is also cultural. Indeed, if we understand ‘culture’ as a set of socially transmitted and shared forms of both perceiving, classifying and conceiving the world, and of feeling and acting, very little of what is human will not, broadly speaking, be culture. But such a general statement would erroneously conceal an essential and sui generis aspect of power relations, and particularly of the acknowledgement or withholding of certain rights or privileges from specific social groups: at any point in time and in any culture with dominating and dominated people, the rights acknowledged to the latter are the result of the history and dynamics of conflicts and power negotiations. The same regards, symmetrically, the grounds for inequality and the privileges enjoyed by the dominating individuals. Thus, the rights of dominated groups are imposed onto the dominating in an essentially political process of conflict and negotiation; the encoding of such rights into cultural rules (together with the cultural encoding of the grounds for inequality, even when such grounds are assumed to be natural or spiritual) is nothing more than the transcription into normative rules of an incidental and temporary correlation of forces, however long-lasting, within social norms and the collective view of the world and ‘human nature’. This means that unless we maintain an essentialist image of ‘cultures’ that considers them static, homogenous, mutually exclusive and isolated, the employment of cultural relativism to people’s rights is abusive and inappropriate.

But there is a second problematic issue, which is simultaneously academic and practical. If the purpose of projecting cultural relativism onto the administration of justice by using the concept of legal pluralism is, as I presume, to promote the emancipation of cultures and societies which are now subjected to the diktat of alien principles and criteria, such purpose would only be possible without inflicting perverse harmful effects if the dominated societies if they were homogenous, harmonious and void of power relations and strong conflicts of interest.

This is obviously not the case in the Mozambican context, or for that matter in any other context that I am aware of. It seems, indeed, that Rousseau’s “good savage” (1978 [1750]) is still able to combine in him the empirical inexistence and the ability to excite some “western” imagination about exotic paradises… Because, in practice, what we are dealing with are greatly diversified and hierarchal communities, wherein inequality and domination relations between groups are, as everywhere else, culturally codified.

On the one hand, this means that regarding local cultural rules as homogeneously representative of the community as a whole is the same as regarding the values and interests of the dominating groups as general. It is also the same as interpreting the local relations of power, inequality and domination based on the legitimating speech that the dominants produced about such relations. In a way, this is yet similar to the long-lasting anthropological interpretation of the Indian system of castes based on classical texts, written by Brahmans – therefore looking to this system and to the highest castes’ domination in it solely from Brahmans’ point of view (Perez 1994).

On the other hand, this means that, by disregarding the existence of endogenous processes of hegemony13 in communities that are considered ‘different’, and by assuming that the dominant values in such communities are ‘genuine’ and representative of the ‘entire’ community (as if the community was homogeneous, and as if the acceptance of such values by the dominated members was not, itself, the result of a process of domination) contributes to the reproduction of the very discrimination and hegemony that exists within communities. In other words, by trying to counteract the abuse arising from the imposition of ‘western’ values in a context of intercultural domination, one is validating the abuse arising from the imposition of values by local dominant groups and the type of dominating relationship employed by these groups upon the subalterns. By calling for the emancipation of an abstract and imaginary community, we are reinforcing the tools of oppression of those who are in fact dominated in the community.

Conclusion: Dilemmas and Possible Solutions

Due to such reasons, I argue that we must hold that ‘culture’ and ‘tradition’ (although central while contextual framework) are not valid impediments to equity and individual rights, or to the protection of people who are most vulnerable due to their situation or status.

However, claiming this is quite different from claiming that when a practice includes formal elements that appear abusive in light of internationally dominant values of equity and human rights, such values should overrule the meanings people give to such practices, and the social consequences they ascribe to them.

capa de 'studies in witchcraft magic war and peace in africa'

capa de 'studies in witchcraft magic war and peace in africa'

I doubt that the dilemma between these two poles, which tend to be considered as the only possible ones, has a definite solution, or even a totally satisfactory one. However, it seems to me that there is a third alternative, which is also relativist and continuously renegotiated. This alternative has the advantage of not being enforced by foreign values, nor to withholding rights denial or reproducing inequalities.

I suggest that in the case of a conflict between ‘cultural’ principles/practices and human/citizenship rights, the criteria applied should not be the dominating rules, whether international or local, but rather the will and point of view expressed by the dominated individuals and groups, about the case in stake. This is certainly not an easy solution. It requires knowledge, participation and transfer of the decision-making power to the dominated and vulnerable, with the state undertaking the burden of challenging local relations of power and domination.

But there is an additional problem that derives from Gramsci’s (1971) connotation of the word ‘hegemony’, when he coined it: the meaning associated with the fact that the dominated accept and integrate into their own ideology principles of the dominant ideology, which were precisely established in order to legitimise the domination they fell victims to.14 As a result of this process, there is always the risk that the dominated, will reproduce the locally dominant ideology by supporting the very practices and principles that oppress them. Considering the above, however, this seems to me to be the least important of possible risks – and, most importantly, this transfers emancipation processes from the field of the external imposition of power to the field of political debate and symbolic and ideological negotiation.

Arrived to this level of generalization, it is now appropriate to return to the starting point and empirical basis of this chapter: sorcery accusations and trials as variations of ‘legal pluralism’ which are capable of clarifying the tensions and limitations of the later.

By doing so, one could argue that sorcery trials are an extreme case within the diverse framework of ‘legal pluralism’ practices, so they should not jeopardize harmless and socially useful mechanisms of conflict resolution and justice providing that are mutually accepted by the parties involved. Indeed, sorcery trials can be contrasted, for example, with the mediation of family quarrels at a police station or a community court, since they involve the resort to spiritual or magical means of evidence and because they may lead to economic despoilment, ostracism, mutilation, induction of insanity, or death of the defendants.

However, we often hear news of verdicts from those ‘harmless’ non-state instances of conflict resolution that obviously abuse the legal, constitutional and human rights of accused citizens, or even their family members – like when the accused are forced to rend their minors daughters in marriage to the accusers, as compensation.

Furthermore, the abuse of dominated and vulnerable individuals and groups may vary in degree depending on the type of non-state ‘justice providing’ institution and on the local context, but such abuses originate from the same principle of cultural legitimacy - and consequently from the same legitimating principle of culturally codified inequalities. Besides, sorcery trials and other non-state justice providing instances may often maintain, as we could see, links and interactions between them. One may argue that sorcery trials are like the extreme pole on a continuum of abuse and domination possibilities; however, all these possibilities (including this ‘extreme pole’) are inherent to the logic of ‘legal pluralism’.

As mentioned before, when we analyze specific examples of sorcery accusations and trials, it is clear that they are not exclusively explanations for misfortune, or mechanisms of conflict resolution and social control. They are also a powerful tool to restate and reinforce the local grounds and relations of domination and inequality, to which the dominated people may adhere either due to the effect of hegemony or because they are potential victims of similar accusations.

This phenomenon gives rise to uncomfortable questionings of a scientific, ethical and political nature, which should not be excluded when examining legal pluralism: Is it correct to use cultural relativism as a presumption for discussion when people’s culturally recognised rights are not, strictly speaking, a cultural but a political phenomenon, a codified result of mutable correlations of forces and domination? Is it reasonable to stimulate practices and principles of legal pluralism when these do not just weaken modernist hegemonies and ideological domination at the global level, but also strengthen relations of domination and hegemony at the local level? Should the state legal and judicial actions protect the local and historically imposed inequalities, or strive for the equity amongst their citizens? Should legal practices and decisions that breach the constitutional and human rights of citizens, against their will, be socially and politically accepted and endorsed? What can and should be done in order to prevent them?

The responses I would give to the above questions have hopefully been obvious throughout this chapter. However, as a foreigner without any sort of decision-making power over these matters, I believe it is more important for me to raise such questions and to appeal for careful reflection, rather than explicitly answer to them.

REFERENCES:

Binsbergen, Win van. 2003. Intercultural Encounters – African and anthropological lessons towards a philosophy of interculturality. Münster, Lit.

Campbell, Susan. 1998. Called to Heal – traditional healing meets modern medicine in southern Africa today. Johanesburg, Zebra.

Dijk, Rijk van et al (eds.). 2000. The quest for fruition through Ngoma. Oxford, James Currey.

Evans-Pritchard, E. E. 1978 (1937). Bruxaria, Oráculos e Magia entre os Azande. Rio de Janeiro, Zahar.

Farré, Albert. 2008. “Vínculos de sangue e estruturas de papel: ritos e território na história do Quême (Inhambane)”, Análise Social, 187: 393-418.

Florêncio, Fernando. 2005. Ao encontro dos Mambos – autoridades tradicionais vaNdau e Estado em Moçambique. Lisboa, ICS.

Gramsci, Antonio. 1971. Selections from the Prison Notebooks. London, Lawrence & Wishart.

Granjo, Paulo. 2004. ”Trabalhamos sobre um barril de pólvora” – homens e perigo na refinaria de Sines. Lisboa, ICS: 153-174.

Granjo, Paulo. 2007. “Limpeza ritual e reintegração pós-guerra em Moçambique”, Análise Social, 182: 123-144.

Granjo, Paulo. 2007a. “Determination and Chaos, According to Mozambican Divination”, Etnográfica, XI (1): 9-30.

Granjo, Paulo. 2008. “Dragões, Régulos e Fábricas – espíritos e racionalidade tecnológica na indústria moçambicana”, Análise Social, 187: 223-249.

Granjo, Paulo. 2008a. “Tecnologia industrial e curandeiros: partilhando pseudo-determinismos”, in Itinerários. A investigação nos 25 anos do ICS. Lisboa, ICS: 353-371.

Granjo, Paulo. 2008b. “Crónicas dos motins – Maputo, 5 de Fevereiro de 2008”, <http: //www.4shared.com/file/61860426/8ead98e0/Cronicas_dos_motins_Maputo_5_feve...

Granjo, Paulo. 2010. “Mozambique: ‘sortir de la bouteille’. Raisons et dynamiques des émeutes”, Alternatives Sud, XVII (4): 179-185.

Granjo, Paulo. 2011. “’Homens na garrafa’ e os limites à masculinidade”, in Granjo (ed.), Família e Lei em Moçambique. Lisboa, ICS.

Honwana, Alcinda. 2002. Espíritos vivos, tradições modernas: possessão de espíritos e reintegração social pós-guerra no sul de Moçambique. Maputo, Promédia.

Israel, Paolo. 2009. “The War of Lions: Witch-Hunts, Occult Idioms and Post-Socialism in Northern Mozambique”, Journal of Southern African Studies, 35 (1): 155-174.

Janzen, John. 1992. Ngoma: discourses of healing in central and southern Africa. Berkeley, University of California Press.

Murdock, George. 1945. “The common denominator of cultures”, in Linton, R. (ed.), The Science of Man in the World Crisis. New York, Columbia University Press: 123-142.

Niehaus, Isak. 2001. Witchcraft, Power and politics – exploring the occult in the South African Lowveld. London, Pluto.

Lakatos, Imre. 1989. La metodologia de los programas de investigacíon científica. Madrid, Alianza.

Maluf, Sônia. 1992. “Bruxas e bruxaria na Lagoa da Conceição: um estudo sobre representações de poder feminino na Ilha de Santa Catarina”, Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais, 34: 99-112.

Perez, Rosa Maria. 1994. Reis e Intocáveis – um estudo do sistema de castas no norte da Índia. Oeiras, Celta.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. 1978 (1750). Discurso sobre a origem e os fundamentos da desigualdade entre os homens. São Paulo, Abril Cultural.

Serra, Carlos (dir.). 2009. Linchamentos em Moçambique II (okhwiri que apela à purificação). Maputo, Imprensa Universitária.

Sperber, Dan. 1992. O saber dos antropólogos. Lisboa, Edições 70: 59-95.

Turner, Victor. 1957. Schism and Continuity in an African Society. Manchester, Manchester University Press.

West, Harry. 2008. “”Governem-se vocês mesmos!” Democracia e carnificina no norte de Moçambique”, Análise Social, 187: 347-368.

West, Harry. 2009. Kupilikula: O poder e o invisível em Mueda, Moçambique. Lisboa, ICS.

- 1. Indeed, the belief in the effectiveness of sorcery is unfalsifiable as it holds a strong “protective belt”, to use the expression coined by Lakatos (1989) for scientific theories. The occurrence of an unsuccessful empirical case could be due to a technical error in spell execution, to the sorcerer’s insufficient power or to the fact that he is a crook, without jeopardising the presumed overall effectiveness.

- 2. According to this reasoning, if, for example, a person was infected by HIV because he/she didn’t know about AIDS, forms of transmission or care required to prevent it, or if, knowing about that, didn’t use condoms regularly, no other explanation is required for such illness. Conversely, if that person used to wear a condom regularly and didn’t, thus becoming infected, an explanation of such fact is required.

- 3. Health and illness are a variant of this general uncertainty domestication system. Being healthy is the normal state of people, but a state that requires harmony between the living, ancestors and the social and ecological environment (Honwana, 2002). Health is also threatened by the lack of care, by sorcery performed by the living and by the disapproval of ancestors – but in line, in this particular case, of the ecological dangers and demands of the spirits to work as traditional healers.

- 4. From the start, and despite the central role that spirits and ancestors assume here, its general principles were similar, for example, to the classic interpretation of Evans-Pritchard on Azande witchcraft (1978 [1937]). For even more similar systems see, for example, Janzen (1992), Campbel (1998), Dijk et all (2000) and Binsbergen (2003).

- 5. This second allegation, which pertains exclusively to the practice of sorcery, is infrequent. This is unlike possession, which is common among “traditional healers” and even the ordinary population.

- 6. The latter aspect is far from being a Mozambican peculiarity. Not only is it often mentioned in the European context, but it is also found in Brazil (Maluf 1992).

- 7. In fact, the person in question is not only accepting social pressure, but also complying with a combination of factors that Dan Sperber (1992) indicates as a rational reasoning to adopt beliefs which are apparently irrational: the person will be believing that something which he can only conceive in an incomplete and approximate way (sorcery under possession) is possible, based on the assumptions and consensus that there are people with complete and precise knowledge of this phenomenon and that, if he were to have that same knowledge, could confirm that this is true – in a process similar to what, for example, makes it rational for a person who is not an expert in astrophysics to believe in the existence of black holes.

- 8. Usually AMETRAMO, the Mozambican Association of Traditional Healers.

- 9. A divination set including bones, shells, stones, coins and other objects chosen by the diviners and their masters, complemented by six half-nuts of nulu (tiakata) and six dorsal crocodile scales (tinguenha). It should be cast and interpreted in the presence of an appropriate spirit in the body of the diviner, and the reading and interpretation of the combined cast items is deepened and discussed with the present people.

- 10. Due to possible legal consequences, I will not disclose either whether these cases (or any of them) were attended by me or narrated by third parties.

- 11. However, the type of entities which are locally acknowledged by the people as conflict resolution providers may vary significantly throughout the country, together with the level of authority and legitimacy acknowledged to each one of them. Compare, for instance, Farré (2008), Florêncio (2005) and West (2008).

- 12. Hegemony is normally understood, within the framework of this type of rationale and dissertation, in the more popular and vague sense of strong and imposing domination, and not in any of the Gramscian connotations that are at the origin of the word. I shall discuss these aspects later.

- 13. I use “hegemony” here in both Gramscian senses of domination of a group, achieved and validated by convincing the subaltern trough ideological means, and of acceptance and partial integration of the dominant ideology by the subaltern (Gramsci, 1971).

- 14. It is this type of processes, for example, that leads mainly women to teach (and to initially pressure) other women to submit to male domination, or make individuals from socially dominated classes to assume that “there have always been the rich and the poor” and that this is a “natural” fact.