The city made him indecisive and gloomy

In the essay “Why do I write”, George Orwell defends that a given author’s topics are determined by the age in which he lives in and lists four major reasons to write: pure selfishness, aesthetic enthusiasm, historical impulse and political aims. For him “no book can truly avoid being politically biased. The opinion that art has nothing to do with politics is in itself a political stand. Orwell argues that every time he didn’t have a political aim, he wrote lifeless books, with meaningless sentences and inflated wordings. However, the political writing he talks about is understood as art, and therefore he pursues an aesthetic experience departing from sheer propaganda.

We can understand this relationship of writing and politics as what Jacques Rancière calls a writing politics, a politics particular to literature. In his most recent book, about which I already wrote here, he speaks about the importance of the realist novel in the nineteen’s century, particularly with Flaubert, moving the literary eye away from the grandiose hero and focusing it on the ordinary man. Since then, and for almost two centuries, writers have turned their attention to the everyday life drama, and to main characters who could be any of us.

This is, to me, the writing politics of Djaimila Pereira de Almeida. Born in Angola, 1982, she grew up on the outskirts of Lisbon, where she is living up to the present. Her debut book, “That Hair” (Leya), a crossroads of fiction, memoires and essay, presents “the tragicomedy of a coarse hair uniting the histories of Portugal and Angola”. In it, focusing on her hair, Djaimilia talks about racism, identity and feminism. She says: “The history of handing womanhood learning to the public space, sharing it maybe with other people, is not the fairy tale of race intermix, but a history of restitution.” Djaimilia’s starting point is the most usual of the usual, a portrait of a part of her being – her hair – so she can address issues held dear to us in present times.

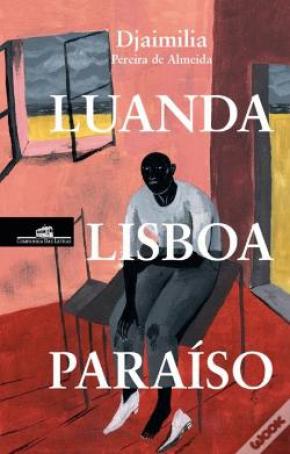

The author has just released Luanda, Lisboa, Paraíso (Companhia das Letras Portugal), a novel traversing those three places, Paraíso being the name of a Lisbon’s suburban area very far from idyllic. It all starts, once more, with a body part. Now, not the hair, mas Achilles heel, who was born handicapped. Cartola, his father, worked as a midwife, with a long career at the Hospital Maria Pia, in Luanda. He felt, from the very beginning, the weight of that flawed heel, what would make him, fifteen years later, switch Luanda for Lisbon, in search of treatment for his son.

Health problems were, and still are, one of the major emigration factors in the old Portuguese colonies. From the humblest to the richest, many travelled to Portugal in search of adequate medical treatment. Cartola saves what he can to take his son to Lisbon, so that he can undergo surgery, and it becomes his escape-city. Escaping not only from his son’s handicap – which won’t be fixe – but also from his wife’s illness who, after her boy’s delivery, becomes confined to bed.

We are talking about an ordinary family – Glória, Cartola, Aquiles and Justina – facing an health issue and the need to help each other. One is the helping stand of the other, but there is a necessary parting. “Aquiles was the limping one and the helping stand”, the narrator tells. By going to Lisbon to help his son, Cartola parts from his wife who, in its turn, controls everything from afar, sending letters which appear now and then throughout the novel. Aquiles is helped by his father, but he ends up seeing in him the immigrant he doesn’t want to be and, over the course of the years, they drift apart, finally turning into two strangers who just share a room or a house. To make it worse, a house which catches fire, gets flooded, falls apart, showing that it is impossible for this family to take roots, to become settled. Maybe that will finally happen after they’re dead, as we can see in the excerpt depicting Cartola at Cemitério dos Prazeres, in Lisbon, imagining how he is going to be placed there. Once dead and buried, he will finally become Portuguese just as the others.

Another crucial issue in this novel is that of identity. Cartola is a child of the Portuguese Angola, he knows everything about the history of the big city, he knows how to conjugate verbs to perfection, but he doesn’t feel Portuguese. He is not Portuguese. He is Angolan, although he never taught his son the language. Considering the emptiness of Cartola’s life, the narrator tells: “He never passed on what he learned. He had put food on the table, but he had allowed for a bond to be broken. It didn’t even teach his son the language. Out of shame, he had forbid himself to become close to Aquiles.” Or, putting it more dramatically: “he had condemned his son to the absence of a personal history, by fear he wouldn’t be able to stand for himself if he knew it.”

Thus, their story becomes the usual story of many immigrants coming from the old colonies in search of medical treatment or of a better life. In Angola, Cartola was a midwife. In Lisbon, he became a construction janitor, and the city made him indecisive and gloomy. Aquiles, who was still a teenager when he switched country, no longer felt Angolan. “From the moment he sets foot in Lisbon, his sees his nationality from the perspective of someone looking at the world from his own bed, feeling hampered, angry and biting his tongue because no one listens to him, no one helps him.” He is from neither place. Aquiles’ identity is shaped in the limbo. That’s why he likes to take a walk in Lisbon “trying to identify his countrymen according to their physical traits and their gait pattern, as if guessing who among them were from Angola made him feel there was a future ahead of him.”

Thus, their story becomes the usual story of many immigrants coming from the old colonies in search of medical treatment or of a better life. In Angola, Cartola was a midwife. In Lisbon, he became a construction janitor, and the city made him indecisive and gloomy. Aquiles, who was still a teenager when he switched country, no longer felt Angolan. “From the moment he sets foot in Lisbon, his sees his nationality from the perspective of someone looking at the world from his own bed, feeling hampered, angry and biting his tongue because no one listens to him, no one helps him.” He is from neither place. Aquiles’ identity is shaped in the limbo. That’s why he likes to take a walk in Lisbon “trying to identify his countrymen according to their physical traits and their gait pattern, as if guessing who among them were from Angola made him feel there was a future ahead of him.”

When he turns eighteen and becomes a man, his father tells him: “Here in this land no-one knows who you are, so you can be anyone”. This freedom every immigrant dreams of is what Justina experiences when she visits her father and her brother in Quinta do Paraíso. But not having a personal history can be as imprisoning as having one. Being anyone doesn’t always work. Further on, the narrator tells us: “He started believing he could be anyone we wanted to be. But the money wasn’t enough, and he didn’t even know where to begin. He had no friends and he kept certain things to himself when talking to his father. Luanda was now a mirage to him and Lisbon was a city with no trees.

Before travelling so as to undergo surgery, Aquiles had only heard about Lisbon from the stories told by his father. After that, the city continued to be a non-place, and the boy became just one among others who felt they didn’t belong to any land. Partly from Luanda, partly from Lisbon, as the lists exchanged by his parents. Glória was always requesting products from the old metropolis, an example of which is the list “mother’s wishes – year 1988”, including deodorant, blood sausage, aspirin. Nestum, elastic bands, hairpins, among other things. Voluntarily, when somebody left Luanda, she sent some food so that her son and her husband could remember the taste of being there.

After five years spent in pensão Covilhã, in Lisbon, Cartola and Aquiles moved to Quinta do Paraíso, on the outskirts of Lisbon, a return to the origins his father’s family. “Having a place was also a way of making themselves disappear like a dead animal buried in the land over which one day it had walked,”, the narrator tells us. It is here, in Paradise, that one also finds the gateway out of the confinement of Cartola de Sousa’s family, through the friendship bounding created in this new address, especially between Cartola and Pepe. “People could no longer imagine Pepe without Cartola (…) If the understanding between two souls doesn’t change the world, not a single part of the world is exactly the same after two souls get along.”

I would say the same about a good novel. It is a part of literature’s politics to point towards a salvation, towards the idea that although we are a reflection of it, we aren’t bound to our age nor our reality. We can always imagine a better place, a better life, a better moment in time. That’s why the art of writing, the one which Orwell defines as political, will always be utopian.

Article originallly published in the newspaper Valor Económico.