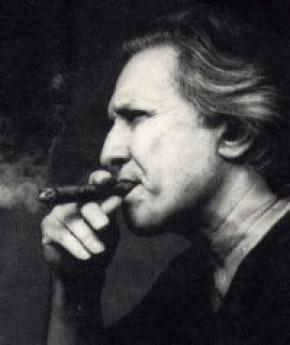

20 Navios”, by Ruy Guerra. The Chronicle and its Melancholy.

The truth is, it makes a perfect triangle, and this greatly pleases Agostinho da Silva. Native of Lorenço Marques (Maputo), a reference point for the New Brazilian Cinema Os Cafagestes, Os Fuzis, Os Deuses e os Mortos, to name a few — with a “Lusitanian” Passport, albeit in a derived language: Ruy Guerra, the cinéaste, turned chronicler. The proof? Sit along the esplanade of the Avenida Atlântica, lounge on the banks of the Tagus for a melancholy afternoon, or, with a few bites of spicy chamussa and a Manica, the local beverage of choice, take a look at the grime of the Indian Ocean, filthy as it may be, and read, keeping count of the ships, of which there are twenty. There are stories for all three — the three points of the triangle, that is: Portugal, Brazil, Mozambique, in no particular order.

The truth is, it makes a perfect triangle, and this greatly pleases Agostinho da Silva. Native of Lorenço Marques (Maputo), a reference point for the New Brazilian Cinema Os Cafagestes, Os Fuzis, Os Deuses e os Mortos, to name a few — with a “Lusitanian” Passport, albeit in a derived language: Ruy Guerra, the cinéaste, turned chronicler. The proof? Sit along the esplanade of the Avenida Atlântica, lounge on the banks of the Tagus for a melancholy afternoon, or, with a few bites of spicy chamussa and a Manica, the local beverage of choice, take a look at the grime of the Indian Ocean, filthy as it may be, and read, keeping count of the ships, of which there are twenty. There are stories for all three — the three points of the triangle, that is: Portugal, Brazil, Mozambique, in no particular order.

The main thing, dear reader, is the surface: rugged, textual, highly lived, the visual frame (like a moral question?) enclosed in the geometric figure, a unit of land-measure amplifying into a square or circle, into the wider continent, into the litho - and hydrosphere where these boats stray.

Sweet Hunters de Ruy GuerraHow does it come about that the director of Sweet Hunters — his most European film, with the cowboy Sterling Hayden, aka Johnny Guitar—should turn to chronicles and publish in the capital of the former empire? Let it be said it is a story not yet chronicled and beyond the chronicle’s scope. But it remains the case that it was in the nineties—already quite some time ago—that Ruy Guerra first thought to run aground on this shore of Language, in order, perhaps, to reflect on cinema. If he lasted two winters, he would have to remember the monsoon, but this particular inlet could provide him neither with foregrounds of tile nor heirloom strains nor an underworld thriller. All this would take place later, in the Botanical Gardens of Rio once again, with the forced getaway Monsanto.

Sweet Hunters de Ruy GuerraHow does it come about that the director of Sweet Hunters — his most European film, with the cowboy Sterling Hayden, aka Johnny Guitar—should turn to chronicles and publish in the capital of the former empire? Let it be said it is a story not yet chronicled and beyond the chronicle’s scope. But it remains the case that it was in the nineties—already quite some time ago—that Ruy Guerra first thought to run aground on this shore of Language, in order, perhaps, to reflect on cinema. If he lasted two winters, he would have to remember the monsoon, but this particular inlet could provide him neither with foregrounds of tile nor heirloom strains nor an underworld thriller. All this would take place later, in the Botanical Gardens of Rio once again, with the forced getaway Monsanto.

In that lusophone island, before Friday arrived, he was busy with the ramparts, mindful, perhaps, of the pirate raids common down the long and jagged coast. It should be said there were precedents. Manuel Ferreira included him in his anthology of poetry about Mozambique. A Ruy fresh out of adolescence, lovesick and devoting himself to naïve rhymes, is revealed to us in No Reino de Caliban III, where social concerns and dislocations of identity are illuminated in a manner which in Knopfli will reach its tragic apogee.

While he waited, two Marches passed—the time of a transatlantic voyage—and he took to writing for a Brazilian newspaper the chronicles now gathered in book form.

Ruy GuerraRegarding the chronicle, it is said to be a “historical text that relates occurrences chronologically”—first assertion—and/or a “journalistic subgenre treating of present-day themes.”

Ruy GuerraRegarding the chronicle, it is said to be a “historical text that relates occurrences chronologically”—first assertion—and/or a “journalistic subgenre treating of present-day themes.”

Exceedingly reductive, as the dictionary would lead us to expect, and may the greats pardon me for saying so—Fernão Lopes, Gois, Zurara, and even—pour cause—Ruben Braga, João do Rio and Bapitsta-Bastos of the Cidade Diária. Because the chronicle is literature. And what is literature? the reader will ask. Let us leave the answer to one who does not scourge himself with the compulsion of words and images—with the anguished uselessness thereof.

Ruy Guerra, born in a leap year, reaches registers of the most varied hue, interior trajectories, humor, melancholy, and reflection, to plug up with words the sieve-like levee of fleeting time and world, a nomad being in twenty paper boats that the narrator watches bandying in the currents of the river, of Brazil; he chooses episodes from his Mozambican youth—that indefinite, poignant, painful matrix—recollecting “The Death of the Old Swazi soldier”; and of course, the magic of cinema, with its particular traje de luces.

The writer of 20 Navios speaks to us of the chronicle and its melancholy, opening with “This (rear?) Window”, where he probes his identitary affiliations—the aforementioned triangle—: “From this window before me, when night falls, and Lisbon turns to dust beneath the anonymous city lights, I may imagine myself in Maputo, Havana, or Rio, or whatever other of my stomping grounds, but I know now that I can never fool myself, because I am inevitably alone, with my afro-latin schizophrenia. How painful it is to be eternally impounded, forever a stranger inside myself, roped, as it were, to my own body. My language is my fatherland, as it is for the poet. And as the feeling of the world is for the other. It’s a great deal. I would even say it’s too much. This window is all that is left for me.”

A psychoanalytic window, this one in Lisbon. Evohe to distance, and a bottle of rum!