Cinema in francophone sub-Saharan Africa: from “Monstration” to contemporary storytelling

Documentary cinema in Africa more or less follows the same trajectory as African Literature. The methodologies and forms of expression are certainly different but the discourse on Africa remains the same, evolving with the continent’s history. In the 1920s, colonial reportage and ethnographic films were already a success. Africa and Africans were filmed subjects. From 1955 onwards, when these subjects became authors of their own images, filmmaking was first and foremost justified by the desire to improve the image of Africans. As with the Négritude movement in literature during the mid 20th century, the positioning of African filmmakers behind the camera essentially arose from a desire to understand their values and African identity. The Canadian filmmaker Pierre Perrault, declared in the same manner that “We started to exist from the moment we stopped looking at ourselves through the gaze of our neighbour.” “Monstration”, demonstration and contemporary storytelling or representing present conditions, giving life to African History.

Samba Félix Ndiay

Samba Félix Ndiay

Before proceeding with our argument, let us pause on the label “African cinema”. Africa is very often considered as a whole and indeed as a country. Today, we speak in the same manner and with the same ease of “African” cinema as we would of Portuguese cinema, making no distinctions between the territorial realities of each. It is true that Portugal alone produces as many films in a year as the entire continent of Africa, if not more. But to reduce the continent to the scale of a country displeases several filmmakers who agree upon representing multiple and singular “Africas”. Thus, we can distinctly speak about North Africa or the Maghreb, West Africa or even Francophone, Lusophone and Anglophone Africa.

Some definitions of African cinema:

a) Films realised in Africa by individuals of African origin

b) Films on the subject of Africa and Africans (regardless of the director’s origin)

c) Films by Africans not restricted by subject matter or the place where the film is made

It is with regard to these three categories of African cinema that we will see how from its birth to today, this relatively young cinematic practice developed separately in the French speaking and Sub-Saharan region of the continent.

I) Monstration

I define “monstration’ as intuitive presentation based on interpretation or the reading one makes of an object on display. It implies notions of discovery and novelty.

“Monstration” in African cinema was celebrated by the colonial enterprise. In the same vain as explorers such as Savorgnan De Brazza, Diego Cao, Livingstone and others who encountered the new lands of the dark continent, the world was confronted with images of men who were often solely labelled as savages, barbarians, primitives and natives.

Colonial cinema and ethnography expanded in the 1920s. The blacks and their exotic settings were filmed subjects consumed through European cinemas and televisions screens. They were restricted to this imagery in order to justify the civilizing project of the coloniser, who was determined to rebuke and deny Africa’s ancestry and ancient civilisations.

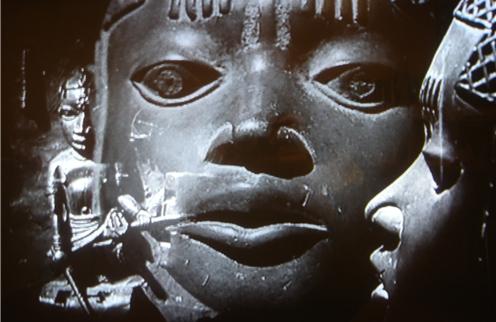

Les statues meurent aussi, de Chris Marker

Les statues meurent aussi, de Chris Marker

In his film “Les statues meurent aussi (Staues also die)” Chris Marker recalls the pillaging of Africa by the West and highlights the threat of extinction faced by this longstanding civilisation. In 1950, the young French director Réné Vautier, released the first anti-colonial film: “Africa 50”. In this work, he denounces the negative implications and the cruelty of colonial power. It is notable that the film’s black subject is shown, protected and represented with humanity.

Jean Rouch, who is considered as the pioneer of French ethno-cinema, would go even further. He let the black subject tell his own story, notably with the film “Moi, un noir (I, a Negro).” The filmed black subject very quickly becomes the narrator of his own history and a proponent of his own images. Moreover, the overriding prerogative of these films lies in the need to re-establish how Africa and Africans are viewed, by and amongst each other.

Malian director Souleymane Cissé highlights this in the biographical documentary made by Rithy Panh: “They filmed use like we were animals….I make films so that we can film ourselves as human beings”

II) Contemporary Storytelling

in 1955, the two Senegalese directors Paulin S. Veyra et Mamadou Sarr directed the film “Africa on the Seine” in Paris. In this work, there depict the lives of Africa students in France and, with this the world is exposed to the first images made by Africans. On the black continent, it is another Senegalese director Ousmane Sembène (most often cited as the first African fimmaker) who produces “Borom Sareth (The Man with the Cart)”. In this fictional tale, Ousmane Sembène attacks the colonial regime.

Afrique sur Seine, Paulin S. VEYRA et Mamadou SARR

Afrique sur Seine, Paulin S. VEYRA et Mamadou SARR

“One day, Africa will speak about itself and write its own history” proclaimed Patrice Lumumba, the Prime minister and key protagonist of the independence movement in Congo-Kinshasha who was assassinated in January 1961. These words reflect the will that drove Africans to take their position behind the camera, as above all they wanted to represent themselves. We see two generations of filmmakers emerging from this, the first directing its critique at the colonial enterprise (e.g Sembène or the Mauritanian Med Hondo) and the second taking on the post-independence authoritarian regimes (e.g. Souleymane Cissé).

The French filmmaker Claude Chabrol stated: “there are two types of filmmakers, the storytellers and the poets.” We can immediately connect the iconoclastic images of the former with African filmmakers who often avoid literal representation. Today, with the digital revolution and access to training, films are produced with more pronounced artistic elements.

The “poetic” style, whose lineage began as far back as the fiction based films of Djibril Diop Mambety or Samba Félix Ndiaye (the father of African Documentary), very quickly became the playground of filmmakers such as Abderrahmane Sissako, Haroun Mahamat Saleh as well as others.

Conclusion

More than fifty years after its birth, African cinema is still very much unknown and ignored. It has indeed garnered increased recognition within the last 30 years. However, its financial dependence on the North, questions of censorship and self-censorship (often more severe than the former) relegate it to the past. Urban and contemporary Africa is concerned with foreigner contexts. It is only within the last ten years that we see the emergence of African productions that connect “plot” (narration) and poetry in depicting the contemporary conditions of Africa.

We are can randomly cite several films such as Abderrahmane Sissako’s “Bamako”, by Karim Miské or Ibéa Atondi’s (Congo), “Un homme qui crie (A Screaming Man)” by Haroun Mahamat Saleh (Chad), “Une affaire de nègre (Black Business)” by Oswald Lewat (Cameroon), “Un pas en avant les dessous de la corruption” by Sylvestre Amoussou (Benin) and « Rwanda pour mémoire (Memory from Rwanda” by Samba Félix Ndiaye (Senegal).