Contemporary Capeverdean Cinema – cinema between islands, archives and the future

Among the many archipelagos that make up the vast ocean of African and Afrodiasporic cinematic production, Cabo Verde is emerging as a space of experimentation, memory, and reinvention. An insular-yet-transnational nation, Cabo Verde sits both at the margins and at the centre of multiple symbolic geographies: Africa, the Black Atlantic, the Lusophone world, the global migrant imaginary, and the Americas. This eminently hybrid positioning is also the springboard for the construction of its own cinematographic language, one still in the making, but already defined by a unique grammar and aesthetic, and a voice much distinctive from that in the cinema about us.

To speak of Capeverdean cinema is, first and foremost, to recognize a film culture still under construction. With only a few decades of meaningful presence and limited infrastructure for production and distribution, filmmaking in the islands has mostly evolved through the efforts of individual creators, often working with minimal resources, outside of any industrial system, and frequently beyond national borders. The Capeverdean diaspora has been essential in this regard, not only as a captive audience and an emotional market, but also as a source of production, education, and artistic inspiration.

Leão Lopes ILHÉU DE CONTENDA

Leão Lopes ILHÉU DE CONTENDA

In the work of early filmmakers like Leão Lopes, whose The Island of Contenda (1995) brought to screen the seminal adaptation of Henrique Teixeira de Sousa’s homonymous novel, we see how Capeverdean cinema can operate as both an archive and reinterpretation of the islands’ social and political history. Lopes not only marked a turning point in the national film canon but also established, with this meticulous work, a deliberate interplay between cinema and literature, cinema and heritage, cinema and identity. His narrative choices—centred around questions of class and belonging—are far from neutral. They highlight how insularity shapes emotions, social hierarchies, and internal migration.

Nuno Boaventura Miranda KMÊDEUS (COME DEUS)

Nuno Boaventura Miranda KMÊDEUS (COME DEUS) Cena de A ÚLTIMA COLHEITA Nuno Boaventura Miranda

Cena de A ÚLTIMA COLHEITA Nuno Boaventura Miranda OMI NOBU Carlos Yuri Ceuninck

OMI NOBU Carlos Yuri Ceuninck SUMARA MARÉ Samira Vera-Cruz

SUMARA MARÉ Samira Vera-Cruz

More recently, the so-called Nova Vaga Cabo Verde (Capeverdean New Wave) has been shaping a new era in national cinema. Directors like Nuno Boaventura Miranda, with films such as Kmêdeus: Eat God (2020) and The Last Harvest (2025), or his much anticipated second feature The Flowers of the Dead, already stirring interest on the international festival circuit; Carlos Yuki Ceuninck, whose documentaries The Master’s Plan (2021) and The New Man (2023), or even his short Dona Mónica (2021) offer socially incisive yet patient, generous, and poetic portrayals; Samira Vera-Cruz, who followed her Buska Santu (2016) and Hora di Bai (2017) with the stylistically distinctive Sumara Maré (2022), her most striking work to date, leaving us to anticipate the release of her hybrid documentary feature Plastic Atlantis (in production); César Schofield Cardoso, whose Bianda (2022) and documentary-in-progress Agu Rixu articulate socio-political themes as integral to Capeverdean culture; and Falcão Nhaga, with Mistida (2022), have all contributed to the development of a film language deeply rooted in Creole realities while open to global aesthetic and discursive influences. These films offer intimate and politically attuned portrayals of the islands, their people, their absences, their restless youth, and their resilient spiritualities. This gaze is a common denominator.

BIANDA RETROSPECTIVA César Schofield Cardoso

BIANDA RETROSPECTIVA César Schofield Cardoso

Indeed, what unites this new wave is less a shared visual style than a common attitude: an insistence that cinema is a tool for emotional, political, and symbolic excavation. These works explore themes such as migration, absence, economic struggle, survival, spirituality, youth, femininity, and colonial trauma, always with a formal sensitivity that resists exoticism and easy binaries. This is cinema that listens, that lingers, that holds space for silence. It is cinema that cares deeply about what remains unsaid—about gestures, voids, and rhythms that resist narrative conventions. It is cinema that stands its ground. It’s cinema-poetry, it’s terra-terra (rooted) cinema, it’s finka-pé (proudly ours).

With all this sense of place and sense of self, we should reiterate that Cabo Verde is certainly not a monolith and nowhere is that more evident than in the many indispensable, challenging, divergent, and provocative contributions from diaspora filmmakers.

MISTIDA Falcão Nhaga

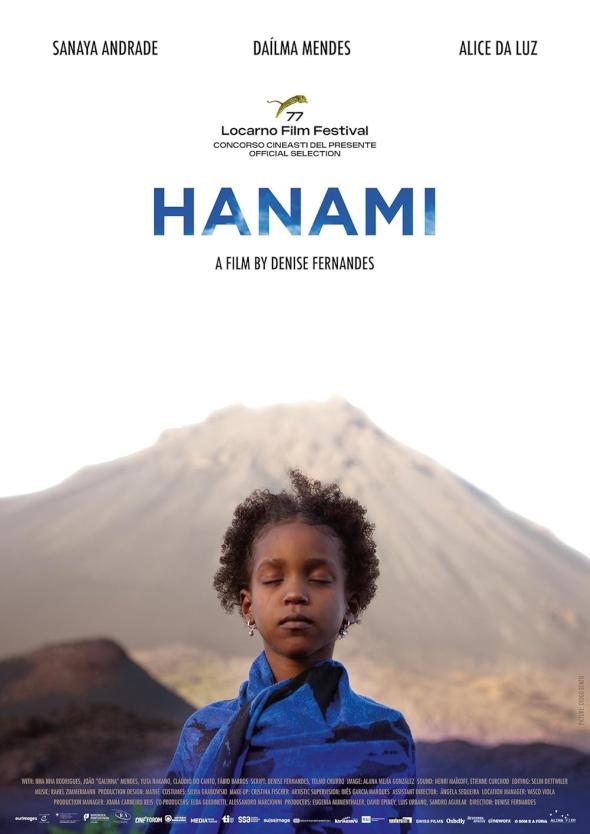

MISTIDA Falcão Nhaga HANAMI Denise Fernandes

HANAMI Denise Fernandes

Denise Fernandes Leopardo em Locarno para Melhor Cineasta Emergente Fernandes

Denise Fernandes Leopardo em Locarno para Melhor Cineasta Emergente Fernandes

Many of today’s leading Capeverdean filmmakers have lived or continue to live outside the archipelago. These are artists inhabiting what Homi Bhabha termed the “third space”—a zone where identity is constantly negotiated, a space historically familiar to Capeverdeans at large. And it is in this liminal space that we find one of the richest convergences with the wider Afrodiasporic cinema: film not only from the Black and/or African experience, but from its dispersal, its colonial inheritance, its complexity, and its ongoing fight for visibility and agency.

Within the context of African cinema, Cabo Verde shares with its neighbouring countries and their cinematic universes a fundamental tension: how to build a self-image after decades of being the object in someone else’s lens? African cinema—or rather, African cinemas—are not merely artistic practices but epistemological interventions. As Frantz Fanon wrote, decolonization is not just a political process; it is symbolic, imaginative, and visual. Cinema becomes a battleground for the power to name, to represent, to reimagine that which Benedict Anderson called the “imagined community”, one that is (re-)invented daily by us all.

In this spirit, films like Timbuktu (2014), by Abderrahmane Sissako, and Atlantics: A Ghost Story (2019), by Mati Diop, or even Karmen Geï (2001) by Joseph Gaï Ramaka provide powerful touchstones. In all these examples, the aestheticization of the everyday, the disruption of narrative linearity, the subversion of the colonial tropes, and the centering of female and collective perspectives become tools of symbolic repossession. These films reject the imperative to explain, instead trusting the viewer’s sensory and emotional intelligence. They resist American-style narrative templates, eschew neat resolutions, often simply end without closure or resolution (such is life), but most importantly, they operate in a different temporality—an African, islanded, Black temporality that can be ethereal, mythical, dreamlike, or elliptical.

From a diasporic perspective, filmmakers such as Raoul Peck, Haile Gerima, Julie Dash, Cheryl Dunye, and Tamara Dawit—alongside, more specifically, Cape Verdean-American veteran Claire Andrade-Watkins, whose self-produced body of work stands as a formidable archival record of our very existence, and the emerging Cape Verdean–Swiss director Denise Fernandes, whose award-winning Hanami (2025) followed the quiet brilliance of Nha Mila (2020), marking a major achievement for this new generation—have all expanded a global cinematic corpus rooted in the legacy of slavery, Atlantic crossings (mentioned or unmentioned), and systemic racism. But also—crucially—in the celebration of Black culture, and of life itself. Not just life in grand historical terms, but in its everyday textures: the mundane, the tender, the quietly significant. These artists create images through what might be called an affective archaeology—excavating the personal to illuminate the political and binding the intimate to the historical. Life, in all its quiet insistence.

In Cabo Verde, where the spoken, sung, and imagined word has long been a tool of resistance, poetic and reflective cinema—often hybrid, experimental, or not even cinema at all, sliding into a transmedia and AR/XR space—have taken on particular relevance. Artists like Lólo Arziki (see e.g. Tales of a Not-So-Prudish Girl), Djam Neguin (see e.g. Xindzuti), Janilda Bartolomeu (see e.g. Written in Water, Evocations & Lamentations), Flávia Gusmão (#4 Mangifera (2022), a film included in five-part transmedia performative omnibus Na Lut@, and dedicated to the late producer Samira Pereira), Sueli Duarte (e.g. Mansu Mansu), the aforementioned César Schofield Cardoso and Samira Vera-Cruz, as well as myself, all form an as-yet-inchoate cinematic generation that dissolves the boundaries between documentary, fiction, performance, and video essay. In our work, cinema becomes less a window and more a mirror-partition, simultaneously reflecting and composing profound identity thought-pieces.

Our films and video art summon the body, the sound, the word, the silence, the time, often transforming scarcity into an aesthetic that we own and exultate. Not because––as William Shatner’s song Common People went––there is anything inherently cool about poverty, but because many of our founding myths indeed come from it (see Ulime (2010) by Tambla Almeida and The 47s: Testimonies That Remain (2022) by Artemisa Ferreira) and because the genetic encoding of poverty and survival has taught us resiliency instinctively. That and the kind of humour that has many a Capeverdean joking that we’ve learned from goats that you can withstand hunger by eating little rocks. Likely none of us has. But we all know it.

DJAM NEGUIN Xindzuti Poster

DJAM NEGUIN Xindzuti Poster Projectos Janilda Bartolomeu Flavia Gusmao Lolo Arziki Djam Neguin

Projectos Janilda Bartolomeu Flavia Gusmao Lolo Arziki Djam Neguin ULIME Tambla Almeida

ULIME Tambla Almeida

Much of the multimedia work of Schofield Cardoso and his ongoing project Storia Na Lugar fits into this lineage of political-poetic essay film, challenging classical structure and proposing a slow, critical gaze, as does my own experimental work, notably Pravda, Zeitgeist Apparatchiks & the Gauche Caviar (2021) and Funaná in Ka Ioca x Fogo n’Txon Futuro (2022), all of which inhabit this hybrid cinematic territory. As does the broad and boundary-defying body of work by Janilda Bartolomeu (centralized under—but also beyond—her ongoing genre-defying and post-colonial practice at The Creole Lens). From a more subversive angle, Djam Neguin stands out as one of the most multifaceted creators, working across media, video-art, videodance, performative cinema, and what might call a Creole Afrofuturism (see e.g. AMI.LCAR, Ka Bu Skeci Tradison).

These experimental expressions—often involving diasporic participation and blending layers of displacement and memory—are not looking for instant resolution. They are cinematic messages in a bottle, cast into the sea in search of something that may take a lifetime (or longer) to find.

Within this fragmented yet vibrant ecosystem, curatorial initiatives such as the Tela d’Pano Terra screening series on contemporary Capeverdean cinema––held five times so far––or Raquel da Silva’s ambitious archival gambit Transistor (announcing soon), alongside the ever-increasing presence of Capeverdean films in top-tier international festivals, from Locarno to Cannes, from Durban to Tarifa, from Leipzig to Tribeca, from Marrakech to Rotterdam, and from Ouagadougou to New York, have all played a crucial role in giving these voices global visibility. Festivals and curated programs are not just screening venues: they are political spaces of alliance, exchange, and recognition. For a cinema landscape as small as ours, they are the key locus of exposure.

Still, the most urgent challenge is internal: how to secure sustainable production conditions? How to train emerging filmmakers? How to build domestic exhibition networks? How to embed cinema within the cultural fabric of Cape Verde? Like any art form, cinema cannot live on passion alone—it demands public policy, infrastructure, archives, education, venues, and critical discourse.

And herein lies a vital point: we cannot become complacent with the idea of cinema as merely a passion project, a hobby, a side hustle pursued by people with day jobs. Yes, cinema is culture, it is art, it is identity. But if we want it to contribute meaningfully to our community’s growth—politically, economically, symbolically—then we must also treat it as what it is: an industry. An industry with all its components: education, technical development, equipment, location scouting and cataloging, production, distribution, exhibition, criticism, festivals, domestic and international markets, regulation, financing. A complete ecosystem, thus, not unlike the one currently being very adeptly built to support entrepreneurship and tech start-ups in Cabo Verde. Cinema, as an industry, is soft power. It is economic output. It is international visibility, cultural tourism, and symbolic export. We’ve already achieved this with music, where Cape Verde punches far above its weight on the world stage. There is no reason we can’t do the same with film and audiovisual. The talent is already here.

African, Afrodiasporic, and Capeverdean cinema is not only about telling stories. It’s about contesting narratives: not only narratives about Africa, Africans, Capeverdeans, and about our diverse perspectives, but also narratives about what cinema is, and what it can be, who gets to watch and be watched, who gets to speak and be heard. It is slow but necessary work. It is the work of re-inscribing our collective imagination with images that belong to us and that, in turn, transform us, and then the world.

In this light, the future of cinema in the islands will inevitably be archipelagic: shaped by dispersed voices in constant conversation with the world, by shared yet reimagined memories, by limited resources but infinite creativity. A cinema made with what we have, and, above all, with who we are and what we dare to imagine or aspire to. A cinema where, in the words of Amílcar Cabral, each gesture is both a cultural act and an act of freedom.

FUNANÁ IN KA'IOCA PJ Marcellino

FUNANÁ IN KA'IOCA PJ Marcellino Programa Tela d'Pano Terra SP22

Programa Tela d'Pano Terra SP22