Young black Portuguese men take police brutality case to court

Six alleged victims say officers beat them until they bled and were bruised and forced them into humiliating positions.

Eighteen months ago, they were defendants, accused of storming a police station.

But since that case was overturned last year, Flavio Almada, Celso Lopes, Rui Moniz, Miguel Reis, Paulo Veiga and Bruno Lopes have been testifying not as the accused, but as victims in an unprecedented trial that has put 17 officers of the PSP - Portugal’s public police force - in the dock.

The new case, currently being heard in court, rejects the version of events previously offered by the police officers, and charges them with physical assault, aggravated kidnapping, inhumane treatment and inciting racially-motivated discrimination, hatred and violence - as well as slander, falsifying witness testimonies and falsifying documentation.

The case dates back to February 2015 and is being accompanied by Amnesty International and SOS Racism, among others.

Rui Moniz, 26, an alleged victim, said he was made to lie face down on the floor where police officers walked and wiped their feet on him.

Rui Moniz, 26, an alleged victim, said he was made to lie face down on the floor where police officers walked and wiped their feet on him.

“We’ve never seen so many police officers on trial facing the same charges,” says Goncalo Gaspar, a lawyer for the defence.

According to Jose Fernandes, a lawyer from the team representing six of the alleged victims, all of them young, black men, “no police officers have ever been sentenced for anything like this in Portugal - and the very fact that there has been an accusation at all is something of a victory for us.”

Lisbon’s Cova da Moura neighbourhood, where most of the plaintiffs live, is known for its proud, predominantly Cape Verdean community.

But the relationship between the residents and police has been tense, with several outbursts of serious violence in recent years, including the killing of 17-year-old Angelo Semedo at the hands of police in 2001, and the death of a police officer there in 2005.

“The kind of policing that these mostly black neighbourhoods are subjected to is exceptional,” says Fernandes, the lawyer. “And I know because I grew up in one. They often turn up in armoured trucks and wearing masks … People are very scared of them.”

Meanwhile, speaking in defence of his police clients, Gaspar says: “It’s a very problematic neighbourhood, where there’s quite a lot of crime and social problems. In this case … a certain amount of force was necessary.”

The officers maintain that the Alfragide police station was “stormed” following an operation in streets of Cova da Moura earlier that same day. During court proceedings, however, a different account has emerged according to the victims.

Various witnesses give evidence that they were dragged into the police station or taken forcefully into custody, and held for two days without being charged, during which time they were racially abused and physically assaulted.

Several demonstrations have taken place in Lisbon with protesters rallying against racism and police brutality.The contradictions begin with a police operation in the streets of Cova da Moura, during which police say a stone was thrown at them. During the same operation, Jailza Sousa, Neuza Correia and Celso Lopes, were shot with rubber bullets - none of them apparently intended targets.

Several demonstrations have taken place in Lisbon with protesters rallying against racism and police brutality.The contradictions begin with a police operation in the streets of Cova da Moura, during which police say a stone was thrown at them. During the same operation, Jailza Sousa, Neuza Correia and Celso Lopes, were shot with rubber bullets - none of them apparently intended targets.

A fourth, Bruno Lopes, told the judges that he was approached by the police in a nearby cafe by officers who asked, “What are you laughing at?”, before hitting him with a truncheon in the face, dragging him bleeding into the police van that took him to the station.

Flavio Almada, 35, a well known community organiser and activist says he was singled out by the police, having gone to the station to find out about Bruno Lopes, who he knew had been arrested.

“One of them pointed at me and said, ‘Get that one, he thinks he’s so clever,’,” he testified.

Once inside the police station, Almada says he was racially and physically abused by various officers.

“They said ‘trash belongs on the floor’, then they threw me down on the floor and carried on kicking me,” he said, also reporting various racial slurs. “Then someone kicked me in the face, I was bleeding a lot and one of my teeth broke. They were kicking and punching me … They seemed to enjoy it.”

Photographs taken immediately after the release of the alleged victims and submitted to the court show the plaintiffs bloody and bruised.

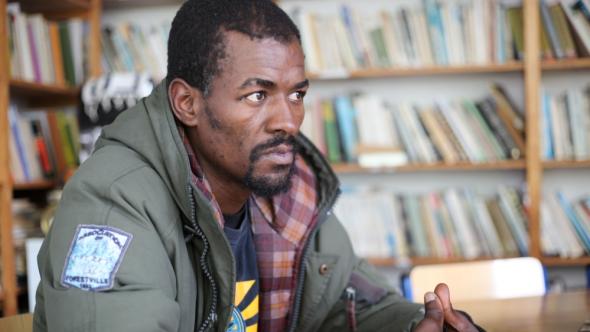

Flavio Almada, one of the alleged victims, says police officers 'seemed to enjoy' physically assaulting him.

Flavio Almada, one of the alleged victims, says police officers 'seemed to enjoy' physically assaulting him.

The physical scars are no longer visible, but while giving his evidence Almada broke down in tears.

“It was like being in hell,” he told the judges.

Meanwhile, 26-year-old Rui Moniz told judges he was approached by police officers after leaving a shop where he was inquiring about a cable TV service for his mother, close to the Alfragide police station.

According to Moniz, the officers said: “Look, here comes an amputee”.

Having suffered a stroke as a child, Moniz walks with a limp and has a splint on his arm.

After officers asked if he had been filming them, Moniz says they knocked his phone out of his hand and punched him in the face, before dragging him into the police station.

“One of them asked for my ID,” Moniz told the court, “and when he looked at it he said, ‘Hey, this one’s actually Portuguese’, and another officer responded, ‘He’s not Portuguese, he’s Pretoguese’” - preto meaning the colour black, and also a racial slur.

Moniz went on to describe being made to lie face down on the floor, where police officers walked and wiped their feet on him.

“A woman came in to clean up the blood on the floor, and she said, ‘This is nothing to do with me, it’s up to my colleagues’,” he told to the court.

So far, the police officers have denied all of the charges facing them.

“They are outraged, they feel they have been victimised,” says the defence lawyer, Gaspar Goncalo, “and they’ve suffered both personally and professionally.”

At least 15 more cases have been opened against police officers in Amadora.Some of the defendants told the judges that the case had taken a toll on their psychological well-being, although most remain on active duty in different locations since the judge denied a petition from the prosecution for all of the agents to be suspended from work for the duration of the trial.

At least 15 more cases have been opened against police officers in Amadora.Some of the defendants told the judges that the case had taken a toll on their psychological well-being, although most remain on active duty in different locations since the judge denied a petition from the prosecution for all of the agents to be suspended from work for the duration of the trial.

The officers also have backing and legal support from the police trade unions.

In Cova da Moura there are mixed feelings about the trial and how it might end.

For Fernandes, who has been working locally for years, “the general public look at this case from the top down - but the community here is looking at it from the bottom up. People here know that if this goes badly, they’re going to bear the brunt.”

Nonetheless, Semedo feels the case is of “huge importance - not only because it sends a strong signal that the police cannot do whatever they want with complete impunity, but also because the attitude here has always been that ‘nothing will ever come of this kind of thing’. But now people have started to realise that something could come of it, after all.”

Since it became public, at least 15 more cases have been opened against police officers in the same municipality of Amadora.

The three judges will hear from more than 100 witnesses and the trial is expected to run at least until the end of the year.

“Personally, I didn’t want to go through all this - of course I didn’t.”, admits Almada, speaking about the trial. “But we have to break the cycle of silence.”

Rui Moniz, left, stands outside the court with lawyers Lúcia Gomes, centre, and José Semedo Fernandes, right.

Rui Moniz, left, stands outside the court with lawyers Lúcia Gomes, centre, and José Semedo Fernandes, right.

Originally published in AL JAZEERA NEWS 27 Oct 2018