If Truth Was a Woman…

What were the artistic influences that you experienced growing up?

My childhood was a training ground for what I do now. Although my mother Ana Arrone was not an artist herself, she exposed me to art. She would bring me books to read, musicians to listen to – she was a reference for the tastes I developed in music and for my visual preferences. She would talk about how young people were feeding their thirst for culture, music, and art in the early days of independence in Mozambique. We listened to Bob Marley, Kool and the Gang, [Queen’s] Freddy Mercury, Prince, and many others. She was able to provide me with an entire world to which I would escape whenever the real world became too rough or too stale. And this entry into a trans-cultural space and language has influenced the manner in which I am approaching life. Although she passed away in my late teenage years, she was able to instill an insatiable curiosity in me. She was magic…

Installation View, Will See You in December…Tomorrow (WSYDt), 2015, Maputo

Installation View, Will See You in December…Tomorrow (WSYDt), 2015, Maputo

Your work Will See You in December…Tomorrow portrays a conversation with your grandfather about his memories of colonial Mozambique. What was that like for you? And what kind of stories do you want to tell through the different media you use – from photography to video to performance?

My relationship with my granddad (Armando Arrone) is one that has remained with me over the years. We’ve always been friends and shared football matches and time in his carpenter’s workshop experimenting with wood, while he would tell stories of colonial Mozambique. I am a proxy war child, born during a period that was very challenging for all Mozambicans. Maputo was crowded by UN workers and the country was on the brink of democracy. I have inherited a city and a country that were formed without considering people like me. Our constitution and laws took a long time to develop – such as the legality around same-sex relationships, which was only revised in 2015; or the rape laws that decriminalize the perpetrator if he marries the victim; or, last but not least, the late developments in family law that were, until very recently, governed by the Catholic church. Outdated laws passed during the colonial era still pervade my experience as a Mozambican living today and give me insight into colonial times. The work Will See You in December…Tomorrow (WSYDt) mirrors these connections with our colonial history and explores what has been unconsciously appropriated or adopted into our national constructs.

In an interview Samora Machel (first president of independent Mozambique) was asked if he thought the liberation movement and political party Frelimo acted too soon. His response was that it had moved when the opportunity presented itself, but I think Frelimo’s ideals were lost after independence. As a result, we don’t have a strong sense of identity, and perhaps this is why there is little involvement in arts and culture. Also, making Portuguese the official language reduced the possibility of diversity in many institutionalized contexts, resulting in bureaucracy and demagogy.

WSYDt foregrounds different narratives – for example, connections with the East which began in the eleventh and twelfth centuries with traders from India and Indonesia bringing fabric (capulana), spices etc. Our appropriation of Portuguese and a broadly Western academic context have become our only apparent connection with the rest of the world. My piece is about questioning these colonial influences.

The stories that I tell are ones that challenge the archive of this Western canon – they want to intervene and expand this archive in order to form new connections with our present lives.

Akona Kenqu, Public Acts, Joanesburgo, 2014, Performance Tedet Time (de Compound to City)

Akona Kenqu, Public Acts, Joanesburgo, 2014, Performance Tedet Time (de Compound to City)

You do not only work as an artist but also as a curator and researcher, for instance for the platform PAN!C. What’s your perspective on cultural collaborations and networks?

Art making is difficult anywhere, and especially so on the African continent. My first instinct is to be an artist and to be as carefree as possible; however, when you are a young Black woman from Africa (excepting perhaps South Africa and Nigeria) it is really, really hard. In Mozambique we don’t have structures to support artists. For this reason I moved to South Africa, where I accepted a position at the Visual Arts Network of South Africa (VANSA).

Video Still I, Sea (E)scapes, 2016, Lisboa Here I have established various programs such as PAN!C, which aim to stimulate art production and its circulation across the continent. For instance the Boda Boda Lounge – a video art festival – has been instrumental in creating platforms that are inclusive. I have learnt that through sharing and participation, diversity happens. I am really weary of a homogeneous representation of Africa and African culture – of a superficial oneness defined by the use of a certain fabric (capulana) for fashion trends, natural hair or by afrobeat, etc.

Video Still I, Sea (E)scapes, 2016, Lisboa Here I have established various programs such as PAN!C, which aim to stimulate art production and its circulation across the continent. For instance the Boda Boda Lounge – a video art festival – has been instrumental in creating platforms that are inclusive. I have learnt that through sharing and participation, diversity happens. I am really weary of a homogeneous representation of Africa and African culture – of a superficial oneness defined by the use of a certain fabric (capulana) for fashion trends, natural hair or by afrobeat, etc.

Capulana fabric, for example, is not originally from the continent but represents early intercultural exchanges. Music styles vary greatly from Cairo to Cape Town, ranging from avant-gardists such as Luka Mukavel (from Mozambique) to movements such as Pungwe. Through the networks that we have been able to create, cultural circulation and exchange can take place.

Video still, Not a Time for Labor, 3 channel video, 2013, Joanesburgo

Video still, Not a Time for Labor, 3 channel video, 2013, Joanesburgo

You consider yourself a feminist. How does this stance inform your artistic practice?

I am a feminist now; more specifically, I am a Black feminist from the African continent. What I mean is that feminism in Maputo may differ slightly from other contexts – for example, women here who don’t shave are not doing it as a challenge to patriarchy – it’s simply a cultural thing.

Forty percent of the Mozambican parliament is made up of women from various parties and cultures, but that does not translate to the inclusion of women in positions of power in the various sectors. My feminism is about challenging conditions that have had little to no impact on the lives of Mozambicans across the board.

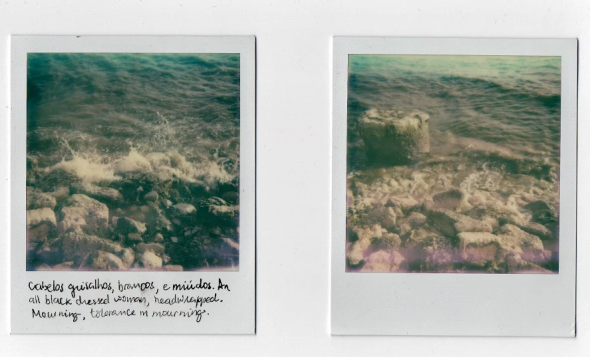

Video Still, Sea (E)scapes, 2016, Lisboa

Video Still, Sea (E)scapes, 2016, Lisboa A Conversation I, Entre-de-Lado, 2013, Joanesburgo

A Conversation I, Entre-de-Lado, 2013, Joanesburgo

What are you exploring at this year’s Dak’Art?

My installation Supõe Se a Verdade Fosse Uma Mulher_ E Porque Não? [Imagine If Truth Was a Woman – And Why Not?] makes connections between slavery and later colonial times, with the presence of elements such as the white wedding dress and a white wall. It challenges constructs of whiteness such as the idea of purity by creating a chart with various resources from the continent that are all white – ivory, cotton, powder.

It comes to the present time and looks at African struggle fighters – the construction of the sole hero- and the possibilities that the archive should include other partners by featuring their spouses names in the conversation, however, open to other additions and manners in which to author our histories.

Published in C&