In the city we are almost predators

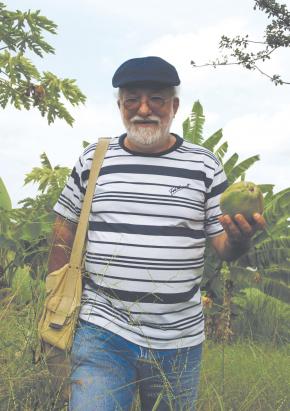

The beard was long and white and the hair long too but flowing loose. The face was burnt by the sun and an enormous love for the Namibe desert, where he had spent his childhood . He had been enchanted by the dunes, which looked to him like mountains of gold glittering in the distance. Samuel Aço is the main force behind the Centro de Estudos do Deserto (Centre for Desert Studies). This is an association in the heart of Namibe, in southern Angola, delving into the secrets of one of the country’s most inhospitable regions.

You have been studying the desert here for a long time. When did your academic interest in the region begin?

You have been studying the desert here for a long time. When did your academic interest in the region begin?

I’ve been researching in this region since 1996. The area runs from Tômbwa to the town of Namibe and the border to the south, along the river Cunene, which goes through Namíbia. It’s a study of informal traders. Some are traditional traders, on foot or with a donkey to carry the load. Others have vehicles.

Does your work cover the whole desert or is it restricted to certain areas?

You can look at the desert from two different angles: there’s the real desert, which is completely inaccessible to us but for these people it is “less inaccessible”. Then there’s the other side, the steppes, which they can travel along on foot, completely at ease, on journeys that can be as long as 300 kms. They take blankets, tobacco, firewater and other products. They don’t use money, it’s all bartering. The locals normally pay with young goats, sheep (sometimes) and heads of cattle, though this is rare.

So how much, for example, is a pack of cigarettes worth?

They deal more in big quantities. A young goat, for example, may be exchanged for two blankets and a bottle of firewater or for three bottles of firewater. What they get is weak in alcohol, but what matters is the quantity.

So what about the “new” traders, those who have trucks, do they use the same trading system?

Yes, though they carry other kinds of products, like fuba, pastas and sometimes rice. But the main products are corn and firewater. They also carry wine and beer. Most of these traders are outsiders, and they have the means to make investment. They discovered this market, they saw that it was not exploited but interesting business, and that’s all there is to it.

Do they use the old routes?

Oh, yes. When I began my study, in 1996, I journeyed between Onkokua and Iona. My car was the first that had been over the road in 24 years. In those days, the only business that was done there was on foot. But it hardly ever rains, there are no new trees nor grasses, so the routes were still visible after 24 years had passed.

For the people who live here, does this type of informal trade have any significance other than economic?

When I started this work, I noticed that the traders who walked (there were no trucks in those days) took very little produce with them, which seemed to mean that there was more to it than merely commercial interest. My research therefore focused on getting to know the reasons that led people to do this journey if they got so little out of it. Maybe there are other values at stake, maybe symbolic, maybe to do with communicating, family gatherings. We are still working on the conclusions.

These people, what ethnic and linguistic groups do they come from?

Most of them are Helelo people, above all from the sub-groups Himba and Tjimba. There are also the Mucubais, who have been studied by Ruy Duarte de Carvalho. But most of the people from the region nearest the coast are from before the Bantus - they are the Vatua, who can be subdivided into Kwebes, Kwis and Kuroca. These names have been known for a long time, but the people they refer to have never been properly studied. In fact, we don’t clearly understand the differences between them.

1978, com o poeta António Jacinto. Nova Oeiras, trabalho de campo.

1978, com o poeta António Jacinto. Nova Oeiras, trabalho de campo.

“We want to get the region known”

The Centre for Desert Studies (CE.DO) is a pioneering project for the country. When it was set up, was the idea to draw the attention of academics to the southern region of Angola?

What happened, in fact, was that at a certain time in my researches, I noticed that it was very important to get some institution to back people like me who wanted to study the region. That’s when the idea came to create an association, and we called it the Centre for Desert Studies. It became a formal institution around a year ago, the aim being to give real support to researchers. In the first phase, what we provided was fundamentally lodging. We ‘re building a unit with two areas for students. It will take up to 20 people.

Apart from the support for academics, what are the basic aims of the project?

We want to get the region known, give the local people a voice and help them. With this in mind, we’re setting up a vocational training centre which will offer a range of courses. We haven’t specified anything yet, but the emphasis will be on local needs. Literacy will be one, undoubtedly, since there are hardly any schools in the area. From my contacts with them, I am certain that handicraft will be one of the fields they will most want to work in. The women, for example, really like the idea of sewing. As road transport comes into the region more, a course in mechanics would also be important. We could then have workshops opening. Apart from training, we want to improve the quality of food and health care.

What areas will the CE.DO specialise in?

We’re open to any researcher, Angolan or foreign, from any field (for example sociology, geology, ecology, anthropology and so on). As an illustration, we are currently putting together a protocol with Namibe University, which has a centre with an environmental engineering course. We want to create a space for students to study there. There is also a project on water which we’re looking into. It may not be apparent, but there’s a lot of water in the desert. You just need to know how to get it up and control its use. Water can be a blessing once it has been brought out, but it also has big dangers, to the extent that it can lead to a lot of cattle being brought together and pastures being destroyed as a result. The cattle can also devour seeds or plants that have not seeded and then the land becomes completely sterile. This has happened in many parts of the desert. The study relating to water is being carried out by the Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia (National Engineering Laboratory). As part of the groundwork, we are also in touch with the Portuguese equivalent and a Brazilian university.

What kind of support do you have at present?

Very little as yet. The association is backed by the provincial government of Namibe. They are paying half of the cost of building the training centre and they have offered a house to be the headquarters of the CE.DO in Njambasana. This is the only village in the desert and is about 27 kms to the northeast of Tômbwa. The other 50 per cent will come from the representatives of Toyota in Angola.

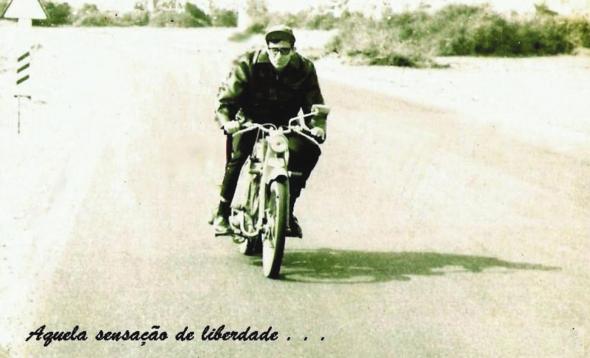

1963, algures em Angola.

1963, algures em Angola.

“Is transmission of the local traditional culture at risk”

What can the desert teach us?

The local people have only the basics for life but they have very sophisticated ideas about how to breed livestock and this mean that can keep animals in areas which would not be any good at all for us. They also know how to keep their animals free from most diseases. The whole social life of these communities is structured around their herds. It’s important to find out how these communities manage to survive, fight against hostile conditions and manage the pastures and the water they find in the midst of a desert.

That is a very up-to-date topic in what is called the “modern world”, which doesn’t know how to cope with the problem of water.

There is a lot we can learn with these people. They may well live in an inhospitable milieu where there’s virtually no rain, yet their health is pretty good and there are no striking cases of malnutrition. The kids in this region are highly sensitive but very strong.

Your study is on-going, but can you let us know what are the “secrets” of the desert people, how they can reach this balance?

For me, the main secret is how these communities have managed to transmit and preserve the memory and the ancestral knowledge from one generation to the next. New and strange elements coming in can, however, alter the whole balance.

Are the traditional communities at risk?

What is at risk is the transmission of their culture. It’s more and more difficult to maintain the conditions that preserve ancestral knowledge. What is important in the anthropology of development is to find ways of taking advantage of technological advances without losing their specific culture and social identity. If we look at the issue in the light of Angolan-ness, the problem becomes even more fraught. If people lose their knowledge of what they are deep down, they are going to get even more confused when faced with the macrostructure of “being Angolan”. Being Angolan will be “something or other” and that’s not what this is all about.

What is “Angolan-ness”, bearing in mind the great cultural diversity of this country? A concept imposed on us by borders that were imposed?

Angolan-ness is living with common values within diversity. There is a common thread to most of the values of the societies and historical/cultural groups that populate the country. Even before the Portuguese arrived there were great political and military movements in what is now Angola from the13th century on. It created an intriguing melting pot. Even the languages spoken across the country are similar, not just for the speaker, but also for the student of language. All this interaction led to an interchange of values between the peoples involved.

There’s one question that keeps coming up: how can you balance modernity and tradition?

By providing space for cultures to react to modern things within their own behaviour patterns. Cultures are dynamic and absorb what is useful from what is modern. They mesh what is new with their own values.

2000, Kikolo, Luanda. Com uma farmacêutica tradicional, trabalho de campo.Why is it that in this struggle between the modern and the traditional, it’s nearly always the first that wins out?

2000, Kikolo, Luanda. Com uma farmacêutica tradicional, trabalho de campo.Why is it that in this struggle between the modern and the traditional, it’s nearly always the first that wins out?

Man has always liked novelty, he has always been curious. And what is modern is always associated with what is very beautiful, attractive, colourful, diversified.

But at the same time impersonal, empty of character.

That is why it doesn’t blend well with collective values, since it leads to many cases where people lose their social personality.

Which brings us to the confrontation between the urban and the rural way of life, and the distorted view each one has of the other.

Nowadays there is a big interchange between the rural and the town environment. Just look at the great number of Angolans who live on the edge of the main towns. The problem is that transmitting the collective memory is jeopardised by town life, because there the fundamental means of passing on knowledge is through the written word. It’s the same in all big societies - the role of families is starting to lose importance in their children’s education.

The individual begins to gain as thee collective loses. Is this the big difference between the town and the countryside?

In towns, education and social behaviour are more through spaces outside the house and through the media. This is an urban-rural problem. Another tremendous difference is the notion of space. In the country, individuals are the master of the space where they lives and they know how to use the space in a harmonious way. In the town we are almost like predators. People can destroy an urban social space because the property in question means nothing to them. Look what happens to the schools and public buildings that are vandalised and left to decay so rapidly. This happens because people don’t see themselves as a part of it all. Those coming from the countryside cannot read these spaces.

Are the institutions at the forefront facing up to this?

Not as rigorously as the problem demands. There is a serious job to be done, a wide-ranging quality operation. Only then can the right responses be found. If we don’t see what is happening and don’t act quickly enough, we run the risk of facing very serious social problems.

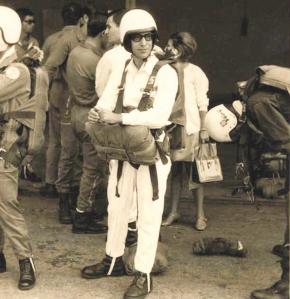

1968 em Luanda. Paraquedismo desportivoSamuel Aço: A desert anthropologist

1968 em Luanda. Paraquedismo desportivoSamuel Aço: A desert anthropologist

Samuel Aço was born in Caluquembe, in the province of Huíla, on 26 June 1945. He lived in Namibe until he was 12, when he moved to Luanda. He studied psychology in Lisbon, but soon changed to anthropology. Before his course finished, independence came to Angola on 11 November 1975 and he felt he had to return. Later on he went back to Lisbon, where he completed his course in 1983.

He lives at present in Luanda, where he teaches at the university. He has produced articles and other works for many publication, both in Angola and abroad.

Photos: Carlos Lousada/ Jorge Coelho Ferreira/ Samuel Aço

in AUSTRAL nº 69, article provided by TAAG - Linhas Aéreas de Angola