Krik-krak, the art of short stories in Haiti

It is considered a treasure of Haitian culture, which reflects the society of the Caribbean country. The krik-krak, the art of telling riddles or tales (kont, in Creole) is a living tradition that unites and transcends generations through oral speech.

The dynamic is simple. In a circle, the narrator throws a “Krik!,” to which the listeners respond with a “Krak!.” The predator continues. “Tim-tim?” And gets the answer “Bwa chèc.” A riddle or tale is then launched.

“What wears white to stay home?”

Fun and satirical, the tales of the krik-krak tradition represent the way of life of Haitians.

Fun and satirical, the tales of the krik-krak tradition represent the way of life of Haitians.

You have to be agile and guess as quickly as possible. If someone answers, “It’s the bed!,” we have a winner. But if after a thousand attempts no one gets it right, the assembly recognizes defeat with a resounding “Mwen bwè pwa.”

In “Assim falou o Tio,” an essential book about the country’s folklore and identity, Haitian anthropologist Jean Price-Mars inquires about the roots of this ping-pong characteristic of krik-krak. “This tradition comes to us directly from the colonial period, (…), it is typical of Breton sailors (…) [but] also from the slave coast [Gulf of Guinea], where the narrator announces his story by a ‘hello’, to which the audience responds with another ‘hello’.”

African influence, or European? The author does not have a concrete answer, but one thing is certain: the Haitians appropriated these formulas and surpassed them, adding elements to them. “[In Haiti], to force the storyteller to report a certain number of short stories, after krik-krak comes another question: “Time, time?” According to the narrator’s disposition, he responds to the demand with ‘Madeira.’ To which the audience asks: “How much will you give?” The final answer will let them know how many short stories they’ll hear that evening: “Nothing, one, two, or more.”

Satire and farce.

Orality says Melissa Beralus in “Krik-krak! (and tim-tim!),” “occupies an extremely important place in Haiti, so much so that even voodoo, the most popular religion, is overwhelmingly preserved through oral traditions, including a strictly oral form of literature called odyans.” Although “the social ritual of storytelling around a campfire is older than History itself, and the Haitian “call and answer” guessing game is rooted in ancient African ways of storytelling,” krik-krak stands out as a “unique treasure of Haitian culture, which reflects and helps create the Haitian society,” she indicates. With “touches of comedy,” “it puts into perspective the ways of life of the lower classes and people living in the countryside, where themes such as property, death, inheritance, and family often resurface in the narratives,” adds Melissa Beralus.

Young people gathered in Bois Moquette at krik-krak time (Franck Fontain)

Young people gathered in Bois Moquette at krik-krak time (Franck Fontain)

The “relaxed and rocambolesque” tone of Haitian riddles and folk tales, analyzes Jean Price-Mars, alternate “between epic, drama,” and above all between “sainete and satire” – “they are more expressive of our state of mind” and portray “the realism and picturesqueness of characters” of the island country.

In this world “expressed in parables and sentences,” the kontes “often take on a symbolic feature,” indicates the anthropologist. To this end, they follow strict setting standards, “requiring the mystery of the night to add intensity to the rhyme of the narration and place the action in the realm of the marvelous.” “Breaching this rule would lead to a terrible sanction,” he warns. “It is traditional to say that a story in broad daylight can cause the death of the father or mother of the person telling it (…) The Bashoto, people of Southern Africa, say that if a story is told during the day, a pumpkin will fall on the narrator’s head, or his mother will turn into a zebra.”

Let’s imagine the end of the afternoon, beginning of the night. A storyteller brings to the scene “nature in full – sky, earth, men, animals and vegetables,” in an old Haitian parable reproduced in “Assim falava o Tio.”

Do you know the adventure Monkey had one day?

Perched high up in a tree, at the edge of a path, the Monkey watched the crowd of peasants heading towards the village market.

All his sympathies were placed on a poor woman who, despite being a little behind the group, walked with quick, diligent steps. The Monkey even felt a little sorry, despite being mischievous and bold. From the peasant woman’s face, he could guess that she thought she could get wonderful benefits from the huge pumpkin she took on her head.

And what was the pumpkin filled with?

This was the question that Monkey asked himself. And so, his imagination soared, while the peasant woman walked hunched over, due to the weight of the pumpkin on her head.

But well, right under the oak tree where the Monkey, perched, was trying to ascertain human thought, the poor woman tripped over a stone and the pumpkin fell and broke, dropping the golden honeycombs it contained.

“My God!” “How terrible!” said the woman, devastated.

The Monkey heard and retained the words. Of the two, he only knew one.

He knew the good God well, to whom he was grateful for having created him, the Monkey, in the likeness of man, almost like a subprimo. But until that moment, he had not yet known the word “terrible.”

He then quickly descended from his observatory, and without wasting any time, he hurried to taste this thing that looked so delicious. He smelled it and then tasted it…

The Krik-Krak festival attempts to preserve this oral tradition of Haiti.

The Krik-Krak festival attempts to preserve this oral tradition of Haiti.

“Damn! It’s juicy!” he said.

In that moment, the Monkey decided to go in search of the good God so that the Creator could offer him a little taste of “terrible.” He left. He walked, and walked, through many savannahs until, finally, the night came.

He arrived at a closed door, beneath which a mysterious warmth filtered. It was the sacred place; it was the terrible precinct.

“Hosanna” was heard from behind the door… The angels were astonished by the Monkey’s reckless step.

As God was conferring, it was the archangel Saint Michael, at that time head of celestial protocol, who received the august visitor and handed him, from the Eternal Father, a heavy bag. He expressly and formally recommended that he not open it until he reached the middle of one of the savannahs that the Monkey had just crossed.

The Monkey, happy, contented, and excited, departed.

As soon as he had arrived at the designated place, he satisfied his curiosity.

Horror! The bag had nothing more than a dog!

The Monkey left like a soul carrying the devil. Ouch!! The dog, a good runner, followed closely behind, warming the naughty curious onlooker’s behind with his breath. Indeed, it was an unspeakable race in its fantastic match.

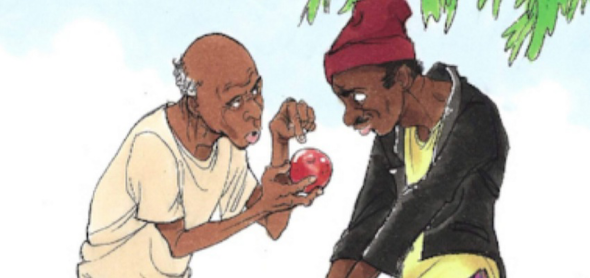

Representation of Bouki and Ti Malice, antagonistic characters from Haitian folklore (Belide Magazine)

Representation of Bouki and Ti Malice, antagonistic characters from Haitian folklore (Belide Magazine)

Finally, thanks to wise stratagems, the Monkey lost his uncomfortable traveling companion and arrived at the house of a hougan [a priest in the voodoo religion, a healer].

“Oof! Doctor, please give me something that will allow me to rid the universe of this rabble that is the dogs. Look, Sir…” and told him about his misfortune.

“I want to help you,” the hougan told him, “It’s quite simple. All you have to do is bring me “such and such a thing” …, from a dog, it doesn’t matter which one, the first one you find. Do you understand? And before the rooster crows three times, I guarantee you that there will not be a dog left, just one, on all the earth.”

“Is that it? It is done then,” said the Monkey.

And he immediately began his campaign.

Two days, then three, then five passed before the Monkey returned to the hougan’s house, with a closed container.

The healer uncovered it, smelled the contents, and said to his visitor:

“Listen, my friend, “this” has I don’t know what scent, which seems familiar to me. Oh! I warn you. If “this” comes from a dog, all dogs will die; but if “this” comes from a monkey, all the monkeys will die.”

“Please, doctor, please… Your comment worries me. In fact, I’m not sure about the cork you just opened. Give me a few minutes… and I promise we’ll know what to do.”

The Monkey left, full of anxiety and never returned. And that is why even today, the dog and the monkey, two brothers in intelligence, continue to be irreconcilable enemies.

Bouki and Ti Malice.

In addition to the parables, in Haitian tales, there are two inseparable heroes: Bouki and Ti Malice. Since ancient times, the country’s words have been inhabited, with lessons on morality and good behavior. According to some sources, folk tales of Bouki were already told in Ghana, with Bouki being a hyena – transformed into a man in Haiti.

Bouki represents “the gentle beast, the unintelligent and cordial force,” and Ti Malice, “the cunning,” explains Jean Price-Mars in “Assim falou o Tio.” But “there is something else,” he warns. And this “thing” has to do with racial representations in Haiti itself. “It is likely that, historically speaking, Bouki is the type of ‘dumb black’ (…) whose supposed turpitude and stupidity were the object of countless jokes and relentless comments from Ti Malice, personification of the ‘creole black’, considered slyer and even a bit rogue.”

Both are essential. “They are the spokespeople for our problems and our sadness, both of them are significant for our habits of assimilation. (…) They are, in their own way, what life offers us in the entire world of stupidity, childish vanity and cautious skill. Both are representative of a state of mind very close to nature,” considers the author.

https://www.buala.org/sites/default/files/imagecache/full/2024/05/krik-k..." alt="Krik-krak en Cayes Jacmel (Anton Lau)

" width="590" height="369" />

Ai-Ai // Ouch-Ouch

One fine morning, Uncle Bouki was walking along the road, when his stomach started to kick and dance – he was very hungry! As he ran home to prepare a meal, he saw a toothless old woman eating on the side of the path.

“Mmmm, that looks delicious,” said Uncle Bouki, “What are you eating?”

Distracted by Uncle Bouki, the old woman bit her lip and shouted “Ouch! Ouch!”

With no time to waste, Uncle Bouki ran to the market in search of some delicious ouch-ouch for himself. The poor man was starving! But, when he got to the market, the vendors all laughed at him, because ouch-ouch didn’t exist!

“I’m so hungry, I can’t think of anything else,” said Uncle Bouki to Ti Malice when he returned home, “Do you have any ouch-ouch?”

Ti Malice wanted to teach Uncle Bouki a lesson. He gathered some thibgs in a bag and gave it to his friend.

“There is your ouch-ouch, the best I’ve got.”

Uncle Bouki took an orange out of the bag and said:

“No, this is not what I’m looking for.”

Then he took out a pineapple and shook his head. Finally, at the bottom of the bag, he found a piece of a cactus.

“Ouch ouch!” “Ouch ouch!” yelled Uncle Bouki, while the cactus’ peaks scratched his skin. “Why did you do that?”

Ti Malice couldn’t hold his laughter and told him:

“You asked for a bit of ouch-ouch, and that was exactly what I gave you!”