A brief reflection on the the Portuguese prison photo project exhibition at the Museum Aljube - resistance and freedom

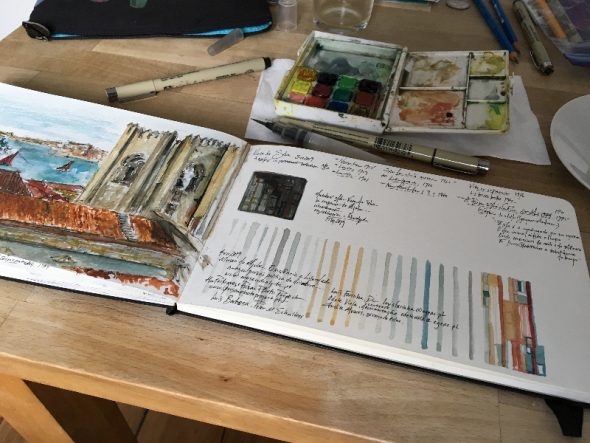

Sketchbook, views from the Aljube, Lisbon (pencil, ink and watercolor drawings) | 2019 | Sharon Lubkemann Allen

Sketchbook, views from the Aljube, Lisbon (pencil, ink and watercolor drawings) | 2019 | Sharon Lubkemann Allen

From the 11th of May to the 29th of September this year the Museum Aljube – Resistance and Freedom is showing an exhibition entitled The Portuguese Prison Photo Project. It consists of a set of photographs of Portuguese prisons by Luís Barbosa, a Portuguese social and cultural documentary photographer (winner of a Portuguese Society of Authors award for work around the exhibition), and Peter M. Schulthess, a Swiss architectural photographer who works primarily in prison spaces.

In this exhibition, the photographers present their distinctive visions of seven contemporary Portuguese prisons, complemented by historical images drawn from national archives. This project began as a purely photographic endeavour proposed and coordinated by Daniel Fink (1), in Switzerland, and later, through the coordination of Cândido da Agra, continued on to the Portuguese Centre of Photography housed in the Cadeia da Relação, a former prison building in Porto. There the exhibition was expanded in two ways, firstly by an international colloquium (2) reflecting critically on prisons, and secondly by a philosophical and empirical study of the spectacle of the prison called The Intentionality of the Image and tragic aesthetics: philosophical and empirical analyses of the spectacle of the prison. This study, conceived and directed by Cândido da Agra (3), took the exhibition as its impetus “[…] but expand[ed] from it towards a critique of punitive reason articulated with a critique of tragic aesthetics” (4).

Here I want to reflect briefly on housing this exhibition within the Museum Aljube – Resistance and Freedom. First of all, we should note that as Luís Farinha, the director of the Museum, insists, putting this exhibition into this space is no coincidence. It is a form of community service. The Museum Aljube is, above all, “dedicated to the history and memory of the fight against the dictatorship and the recognition of resistance in favour of freedom and democracy”, but it has also been a stage for temporary exhibitions and other activities that are not circumscribed by what this space represents today in Portuguese society, but which have a broader public educational remit. While the objective of putting this exhibition in the Museum seems straightforward, it can generate questions about the coexistence of two narratives in one space. That is, this exhibition about contemporary Portuguese prisons is taking place in a space that was a penitential establishment with very particular characteristics during the Estado Novo period. The site’s memory is still very present, above all among those who were detained there. In the contemporary context this museum has come to be associated with the darkest elements of the prisons of that period. In the words of its director, the new exhibition sits in a place with “a very powerful – a too powerful – context” (5). The Aljube, which has housed its current Museum since the 25th of April 2015, functioned as a prison of the International and State Defence Police (PIDE), between 1928 and 1965 (6). But the history of this space is long and complex. Before being a political prison, it was a penitentiary for people convicted of regular and social crimes as well as for undocumented foreigners. These detainees ended up cohabiting with people imprisoned for crimes of opinion during the Estado Novo. After 1934, the PIDE appropriated some Portuguese prisons to detain political prisoners. The Aljube was one of these. It is not known how many people passed through the Aljube, not least because its records of entry has still not appeared. This is a situation that is not exclusive to the Aljube: in Portugal as a whole it is still not known how many people were held as political prisoners. Even though we know that around 30,000 were tried and convicted, this number corresponds to only a portion of those detained, as not everyone was tried. Many individual case histories have disappeared, and those which do exist are scattered across various sources, many in former colonies (7).

The Aljube was never a high security prison. It housed spaces with different functions and statuses: one section was for solitary confinement, whose principal objective was to weaken individuals before being interrogated; there was a large hall which held convicts considered less dangerous and/or those waiting to be interrogated or transferred; there was another space with better material conditions reserved for people of a higher social status with relatively more privileges; and there was the infirmary, known to be the place where detainees were tortured before being transferred to the headquarters of the PIDE in Rua António Maria Cardoso in Lisbon.

The Aljube functioned above all as a site of transit, a kind of depositary of detainees who came from various parts of the country and who were later, if it was considered necessary, transferred to the PIDE headquarters to be interrogated and/or moved to other prisons. Thus, this Museum represents some of the most characteristic facets of the Portuguese dictatorship: detention for crimes of opinion; torture; and murder of defenders of freedom. This space, therefore, has huge symbolic significance as a place to host an exhibition about contemporary prisons, and it matters that the two distinct narratives are not confounded.

The Portuguese Prison Photo Project invites its viewers to consider the work of two photographers on regular prisons in Democratic Portugal of the 21st century, accompanied by other photographs of prisons selected from diverse national archives. The Aljube Museum, meanwhile, “is a musealised site and a historical museum that intends to fill a gap in the Portuguese museological fabric, by projecting the appreciation of the memory of the fight against the dictatorship onto the construction of an enlightened and responsible citizenship, and by taking on the struggle against the exonerating and, often, complicit silencing of the dictatorial regime that governed the country between 1926 and 1974”.

The history of the Aljube and the exhibition that it currently houses are two unquestionably distinct narratives. They relate to different types of punishment and different types of detention in historical and political contexts which cannot be confounded with one another. But in co-existing in this spaceA BRIEF REFLECTION ON THE THE PORTUGUESE PRISON PHOTO PROJECT EXHIBITION AT THE MUSEUM ALJUBE - RESISTANCE AND FREEDOM 4 ISSN 2184-2566 MEMOIRS is funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (no. 648624) and is hosted at the Centre for Social Studies (CES), University of Coimbra. time, even temporarily, these narratives together have the power to interpellate us to consider the complex and multifaceted problematics of contemporary punitive societies. The Museum Aljube is a particularly conducive context in which to question ideas of external and internal threats, security and insecurity and forms of terrorism. These are ideas, indeed, which are in part responsible for the resurgence of discourses which legitimate practices that democratic regimes had seemed to overcome. _________________ (1) Supported by Association Recherche Prison Suisse (ARPS). (2) It led to two international conferences: Prisons in Portugal and Europe: History, culture and photography” (Centro Português de Fotografia, outubro de 2017); Prisons in Portugal and Europe: Regimes of Detention and Monitoring of Regimes International conference (Museu do Aljube e Faculdade de Direito da Universidade de Lisboa, Maio de 2019). (3) Supported by ARPS, by the Associação Internacional de Criminologia de Língua Portuguesa and by the Fundação Minerva - Cultura - Ensino e Investigação Científica. (4) To understand further this theoretical approach and the dimensions and hypotheses of the study see Cândido da Agra “Exposição e Pensamento Crítico”, Prisões em Portugal e na Europa - história, cultura e fotografia: abordagens comparativas – Atas da Conferência Internacional, Porto, Centro Português de Fotografia, 2017, pp 12 – 15. (5) Testimony gathered on 3rd of June 2019, Aljube Museum. (6) In 1965 the Aljube stopped being a prison and became an office of the services of the Ministry of Justice until the 25th of April 1974. (7) Information collected on the 3rd of June 2019 in the Museum Aljube. For further on this consult, for example, Fernando Rosas, Luís Farinha, Irene Flunser Pimentel, João Madeira e Maria Inácia Rezola, Tribunais Militares Especiais e Tribunais Plenários durante a Ditadura e o Estado Novo, Lisboa: Temas e Debates, 2009.

MEMOIRS is funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (no. 648624) and is hosted at the Centre for Social Studies (CES), University of Coimbra.