Maria Eugénia: a woman like the others

Heroines of the imagined nation

In general, Angola’s foundational narratives concerning the emergence of modern nationalism and the war for independence tend to provide homogenous and masculinized readings of the anti-colonial struggle (Paredes, 2015). This is partly due to the sidelining and silencing of dissidents or rival movements to the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), a party which, by holding post-independence state power, monopolized historiographical narratives about Angola’s liberation struggles. In this way, the recognition of women’s contribution in this phase necessarily passed through the monolithic ideological sieve of this party. Therefore, the female agents of history who deserved to be highlighted became symbolic representations of a hegemonic partisan narrative. They are heroines who mirror mythical configurations of leadership and audacity essential to the anti-colonial universe and who reappear in the post-independence present as statues. In this context, we highlight the full-body statue of Njinga Mbande (1581 - 1663) in Largo do Kinaxixi, Luanda. There are descriptions of Queen Njinga, governor of Ndongo and Matamba from the 17th century, in documents by Father Giovanni António Cavazzi de Montecúccolo, António de Oliveira de Cadornega and Fernão de Sousa, which inspired myths of unprecedented resistance against colonial occupation. Rocha (2022) analyzes the accounts of these three authors and questions the possible motivations behind the representation and adjectives used to describe the queen, highlighting her virility, intelligence and even possible androgenic character, and her condition after converting to Catholicism and submitting to the Portuguese in the last decades of her life. The author thus questions the integrity of these narratives, given the ambiguities and contradictions of contemporary interpre tations of circumstances arising from 17th century socio-political contexts (B. S. Rocha 2022, 247).

With regard to women ex-combatants who took part in the MPLA’s anti-colonial struggle, there are many autobiographies, biographies and studies on their life histories and their role in achieving independence. Prominent among the MPLA’s heroines is Deolinda Rodrigues (1939-1967), immortalized in a bronze bust in the square that also bears her name in Huambo. Her contribution to the anti-colonial struggle is undeniable. Deolinda Rodrigues was a poet, writer, guerrilla fighter and militant and the only woman to sit on the MPLA’s Steering Committee in the 1960s. She also co-founded the Organization of Angolan Women (OMA), as well as being a relative of Roberto de Almeida and Agostinho Neto, key figures in the MPLA. However, she also resented her status as a woman, writing in 1964 in the diary she left us: “I’ve been told I’m not going to Ghana because I’m a woman […] This discrimination just because of my sex revolts me. If I find myself outside this erudite and masculine MPLA, I won’t be returning soon” (Rodrigues, 2003). Margarida Paredes (2011) affirms that her militancy turned her into a mythical figure in the country’s liberation struggle but silenced her life story, both inside and outside the political movement.

After the struggles for liberation and the civil war that followed, questions have been raised about the selective representation of national heroines by one political party rather than others. Studies have also emerged on the crucial participation of rural and urban women in the guerrilla war, who contributed anonymously through the transportation of weapons and logistics, as well as healthcare and education in the woodland (Paredes, 2015). Although guerrilla fighters of both sexes belonging to the lower echelons have, to a certain extent, been relegated to the role of extras, it is women’s voices in the anti-colonial struggle that have literally or figuratively remained subordinate to the influx of male enlightenment, making them “non-beings” or simple supporting actors in the project of Angola as an imagined nation.

Militants and partners of nationalist revolutionaries

Another group overshadowed by the dominant narratives is that of the partners and wives of anti-colonial nationalists during their exile from 1950 until Angola’s independence. In this group, the most prominent are Sarah Maldoror (1929-2020) and Ruth Pflüger Lara (1936-2000). Sarah Maldoror, of French and Guadeloupean origin, was one of the first women to direct a feature film in an African country. Her cinematographic work was characterized by her militancy associated with the struggles against colonialism, creating a multifaceted oeuvre of particular relevance in the context of Portuguese-speaking African countries (BUALA, 2021). The focus of her professional and personal attention during the 1960s and 1970s was the second wave of African liberation, especially in Guinea-Bissau and Angola, motivated by her union with Mário Pinto de Andrade. Having become lifelong companions in 1956 in Paris, where Pinto de Andrade had been living in exile since 1954, Maldoror accompanied him to Guinea-Conakry in 1959, at the invitation of the new head of state, Sekou Touré, who, after Guinea-Conakry’s independence in 1958, established his capital as the new stage of African anti-colonial resistance. Maldoror’s statement in a 1974 interview is interesting: “I’m only interested in women who fight.” A statement that corresponds to her non-conformist and feminist attitude. In her commitment to a cinema for the people and for women, Maldoror wanted to inspire women who sought to work in cinema and thus increase their number in the film industry. A necessary step, since, in her view, “In Africa as in Europe, women are still slaves to men. That’s why she must free herself.” A sentiment that runs counter to the reality of the time, especially in an Arab country. Maldoror paid the price. In 1970, the Algerian government confiscated the reels of her feature film about the PAIGC’s struggle for independence in Guinea-Bissau, titled Des fusils pour Banta, expelling her from the country, and the film was reported missing (Tolan-Szkilnik, 2023).

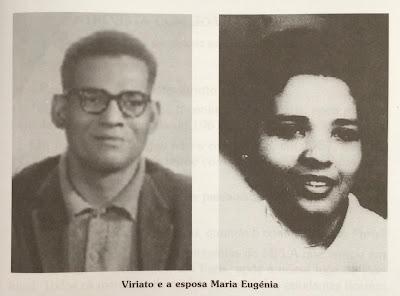

Viriato da Cruz and Maria Eugénia

Viriato da Cruz and Maria Eugénia

Another woman closely linked to Angolan nationalism was Ruth Pflüger Lara, a Portuguese woman of German-Jewish origin and wife of Angolan nationalist Lúcio Lara, one of the MPLA’s main ideologues. Ruth Lara was likewise one of the many women who accompanied their respective husbands on their pilgrimages to various countries, standing by their side and collaborating in their political activities, initially in Europe, then in Africa, from the Anti-Colonial Movement (MAC) to the formal establishment of the MPLA, whose leadership was installed in Conakry in 1960. Ruth Lara arrived with her son in 1960, coming from France via Morocco on an adventurous boat trip. She lived in Conakry until 1963, working and collaborating closely with the group that included Hugo de Menezes; Mário Pinto de Andrade and Sarah Maldoror; Amílcar Cabral and his first wife Maria Helena Rodriges; Viriato da Cruz and his wife Maria Eugénia; the doctor Eduardo dos Santos and his wife Judith (Mariazinha); Dr. Américo Boavida and his wife Conceição; Gentil Viana; Marcelino dos Santos and many others (Garcia, 2014).

Ruth Lara, notable for her organizational spirit and the integrity of her militant commitment to the ideals she defended, ended up departing from the MPLA in the post-independence period, never exercising party functions again and opting to stick to her professional activities as a translator, devoting herself to her family and friends. In 1990, she was offered a “1st Class Guerrilla Fighter” medal, a high distinction for those who fought for Angola’s independence. Ruth Lara refused because she didn’t “feel comfortable with a medal like that of comrades who gave their lives, or who risked it, who engaged as combatants, which I never was, not because I refused to do so, but because at the time I wasn’t allowed to.” In a posthumous tribute in a Cape Verdean newspaper, Garcia notes that Ruth Lara: “was not a guerrilla fighter, but she was certainly, contrary to what her modesty led her to believe, a great combatant” (Garcia, 2014).

Maria Eugénia: a woman like the others

Queens, militants, guerrilla fighters, arms carriers, poets, filmmakers, teachers, nurses, cooks, laundresses, servants, wives, mothers, companions, clandestine women, widows or sisters, the universe of political and anti-colonial women who gave birth to the Angolan nation is extensive. But not all women wanted a medal of recognition for their participation in the anti-colonial struggle. Even more so when, after Angola’s independence, that participation was tainted by the experience of hearing at rallies that the person she had married in exile was accused by the MPLA of being a “revisionist and fractionist.” This was the case with Maria Eugénia da Cruz (Santiago, 2018).

Maria Eugénia Leite Nunes was born in 1928 in the Angolan interior. Educated in Portugal from 1932 to 1947, she returned to Angola where she worked from 1948 to 1959 as a civil servant in customs and later in the post office. The year 1959 was marked by major political mobilization in Luanda and a subsequent siege by the International and State Defense Police (PIDE). Maria Eugénia, who had contacts with the (Portuguese) Communist Party, decided to go to Lisbon. There, in 1960, she chose to leave Portugal after being notified by PIDE. She considered fleeing to the Soviet Union, yet spent four months in France, where she contacted Mário Pinto de Andrade and in 1961 decided to go to Conakry, where the MPLA Steering Committee had been set up in the meantime, headed by both him (president) and Viriato da Cruz (secretary-general).

Thus, as if it were a natural path, Maria Eugénia da Cruz would be part of that generation of Angolan, Guinean, Mozambican and Cape Verdean exiles who, in the 60s, passed through Rabat, Conakry, Alger and the two Congos. Despite being financially autonomous and not feeling personally discriminated against, Maria Eugénia was sensitive to the “colonial condition” inspired by her political conscience, motivating her to take action in the face of the circumstances of her time, a fact that makes her an unusual woman, not only in that specific era, but in any era that demands rejection of convention and conformism in the face of an unjust social order. Maria Eugénia was not a guerrilla fighter, nor a nurse, nor a political counselor to the nationalist movement. She joined those who wanted to change Angola’s destiny. She was a comrade and the wife of an Angolan nationalist. In various cities and countries, she met Amílcar Cabral, Mário Pinto de Andrade, Hugo Menezes, Lúcio Lara, Matias Miguéis and Viriato da Cruz, her future husband. Her story is just one of thousands of other stories submerged in the narrative of modern Angolan nationalism. She didn’t lack risky sojourns in Africa and China, nor deep trials of rawness and pain, to which was added the bitter silence of someone who doesn’t even dare to claim a medal or a mention. Maria Eugénia da Cruz is “simply” the widow of Viriato Clemente da Cruz, one of the greatest poets of his generation and a tormented Angolan nationalist, whose political career dismantles the myth of heroism and integrity of those involved, because in the end, who were the traitors and manipulators when we look in the rearview mirror and reflect on Angola’s history?

The miseries of exile

The 1960s and 1970s, at the height of the Cold War, the Sino-Soviet conflict and Maoist fever, are described by Adelino Torres as decades that brought together millenarianisms and dichotomies without middle ground. They fluctuated between good and evil, between romanticism and disbelief, between exaltation and despondency (Torres, 1998). For his part, Edmundo Rocha (Rocha, Soares and Fernandes, 2008) mentions that later analyses of the formation of anti-colonial movements make allusions that create the false impression that those times were true academies of revolutionary thought; when in fact, that era was characterized by much “precariousness, improvisation and lack of experience” (E. Rocha, 1999).

Motivated ideologically but also driven by the unpredictable whirlwind that was this period, Maria Eugénia first settled in a hotel when she arrived in Conakry, moving in with the doctor Eduardo dos Santos and his wife Judith (Mariazinha) afterwards. Always helpful, she began by organizing the MPLA archives and furthermore:

“(…) I used to help in the office… [They]… were all very busy… I didn’t even have a chair to sit on because the chair […] had broken legs (…) and the typewriter also had to be held with one finger so the lid wouldn’t pop off… the filing cabinet was all disorganized…” (M. E. Cruz, 2010).

Typewriter

Typewriter

Viriato da Cruz and the other leaders met frequently, but did not discuss the contents of their conversations with the women, even during the tensest political moments (M. E. Cruz, 2010). The men assembled and discussed alone among themselves, often traveling to take part in international conferences. A situation comparable to that of the Portuguese Communist Party’s (PCP) militants in Portugal’s underground in the 1950s and 1960s, a period in which, despite the demands of the women’s wing for greater participation in political work, “as in everyone’s life, it was also implicit in the communist ranks and, for better or worse, was accepted by everyone, that they in fact had a secondary role.” The role reserved for women was not limited to emptying ashtrays before or after meetings, cleaning and washing like any housewife. The more educated militants (generally belonging to the petty and middle bourgeoisie) typed and proofread texts, functions considered “technical work” (Barradas, 2004, 61-62; 87). Maria Eugénia, who had completed the sixth grade in a Portuguese lyceum, had “higher education” from the perspective of that time, but, nevertheless, in interviews nothing indicated that she felt belittled for not taking part in the “men’s meetings” (M. E. Cruz, 2010).

The admiration she had for Viriato da Cruz was certainly a great foundation to endure the tragic course of their lives. More than half a century after the floods of history, Viriato da Cruz was posthumously awarded the Prémio Nacional de Cultura e Artes (National Prize for Culture and the Arts) in Angola, in 2018. Maria Eugénia remembered her “husband as a man with an interior like fire. Everything was directed towards his Angola, but in connection with the whole world. He was a person who had no limits, such was his vision.” (Santiago 2018)

In the meetings he didn’t attend, in the constriction of exile when he was alone with his wife, perhaps he kept quiet about the discouragement that lurked in the midst of the comings and goings of anti-colonial nationalist leaders for meetings to articulate strategies and define anti-colonial ideology. Before Conakry, still in European exile, Viriato da Cruz had already vented his frustration in a letter to Lúcio Lara dated December 6, 1959, naming the obstacles to the creation of an effective and efficient anti-colonial movement, and above all, one that would be respected by international organizations, indicating that he was slipping over the precipice of doubt: “In short, I got tired of writing a lot. Was it worth it? I’m deeply suspicious of the usefulness of my efforts.” Lúcio Lara, the movement’s eternal pragmatist, replied: “(…) forgive me for saying so, [but that’s] idealism. We remain (and are) men, not heroes. The struggle is disorganized” (Lara, 2006).

Although perhaps too idealistic and, as such, naive, Viriato da Cruz would defend his convictions to the last consequences. Before the MPLA’s second congress, which took place in Léopoldville/Kinshasa at the end of 1962, Viriato da Cruz wrote a letter to Angolan students in which he argued the importance of the MPLA being headed by Black leaders, claiming that the nature of colonialism lead to the rural masses identifying Mestizos and assimilated Blacks with colonial oppression, which “constituted fertile ground for maneuvers to divide the people.” Thus, it was “pure idealism to admit that, from one day to the next, without the liquidation of colonial conditions (…), the majority of men in a colony can live in the best harmony and mutual understanding.” On the basis of these suppositions, he advocated that “non-blacks continue to be engaged in the struggle with all their soul, but also with a spirit of disinterest in relation to the hierarchy of political organizations”, so that “the delegation of Angolan students [to the congress] should be constituted as much as possible by blacks (…)” (Lara, 2006).

At the MPLA Steering Committee meeting on May 21, 1962, Da Cruz submitted his resignation, arguing that it was not a concession to the União dos Povos de Angola (Union of Angolan Peoples) (which accused the MPLA of being a movement of Whites and Mestizos), but was in the interests of the people. Adding:

“Colonization was done on the basis of racism. No effort was made for the education of black people (…). I am convinced that I don’t carry out a racist policy [nor do I] believe that the Movement will give in because of racial problems (…). A committee formed by mulattos will not be able to give a watchword that will be accepted (…). The problem of Angolan liberation and citizenship are different problems [and] what people have forgotten is that the struggle for Angola is a struggle for the demands of black people” (Lara, 2006).

Da Cruz proposed positioning the lighter Mestizos in the rear. His political choice of self-racism, excluding himself from the forefront of the movement, was to prove fatal, generating a serious split within the MPLA, marked by the rivalry and antagonism that arose with the entry of Agostinho Neto as the movement’s new President. Effectively, Neto differed from Da Cruz not only ideologically, but also on the nationalist forces’ strategy and their external alliances. On July 6, 1963, six months after the first National Conference, Da Cruz was formally expelled from the MPLA, along with his comrade and vice-president Matias Miguéis and José Miguel, for not having heeded the decisions of the conference that put their theses in the minority (Rocha, Soares and Fernandes 2008).

In an interview, João Vieira Lopes said that after his expulsion from the MPLA, alongside the debacle with the FNLA in Leopoldville (Congo) and other humiliations, Viriato was never the same:

“(…) I met Viriato a few times, and I saw a very different one from the one I had known. He was a Viriato deeply disillusioned with those ideals he had instilled in us, a Viriato who was searching for a path, which he had lost, he criticized everything and everyone and frankly I didn’t recognize the same Viriato.” p. 117) (Rocha, Soares and Fernandes 2008, 117).

In 1963, Da Cruz officially married Maria Eugénia. Officially united for better or for worse, in sickness and in health, until death do them part. After Algiers, Da Cruz spent a period of uncertainty in Paris, but left definitively in 1966 for Beijing, China. Maria Eugénia and Marília, his daughter who was born in exile in Rabat in 1963, joined him later. In an interview, she recalls:

“(…) they [other exiled nationalists] didn’t want to have any contact with Viriato either… Who knows… it was something, yeah… because he was a renegade… he was the pariah… the pariah of the movement… they even made it up that he was out there all silly begging and all ragged… There was a version like that…” (M. E. Cruz 2010).

Maria Eugénia Cruz and her daughter Marília

Maria Eugénia Cruz and her daughter Marília

An image of fateful irony, articulated by the opportunity to discard the “political man” who believed in a Marxism-Leninism yet to happen in the Soviet Union, in Cuba and even less so in China, as his correspondence from the last years of his life shows. And so, the discredited political man metamorphosed into a character from his famous poem “Namoro,” “Benjamim, dirty, ragged and barefoot at Mr. Januário’s ball.” Did he really go around the streets of Algiers, dirty and silly, begging for alms? Such an image certainly filled his political antagonists with joy, because cruelty was and still is an intrinsic part of the political struggle.

So, where else can we find encouragement for life if not in music? At least there is music at every moment. Marília da Cruz says that her father appreciated “N’gola Ritmos, Conchita de Mascaranhas, Ray Charles, Louis Armstrong, Dorival Caymmi, Jacques Brel and Ella Fitzgerald.” For her part, her mother still likes: “Fado, Édith Piaf, Charles Aznavour, Duo Ouro Negro, Conchita de Mascarenhas, Lilly Tchiumba, Elias Dia Kimuezo, N’gola Ritmos, Carmen Miranda and Ângela Maria” (M. d. Cruz 2024).

The music presents a path of light to the inexorable end, about which there could be no premonition. Viriato da Cruz passed away in 1973 in Beijing. His thin body was taken from the hospital where he had died trapped between wooden slats. The rigid body bounced around in the body of a military car. The impromptu funeral and the despair of unexpected widowhood. Maria Eugénia, who had left Luanda in 1959, returned in 1974 with her daughter. A year later, they attended Angola’s “Dipanda” festival. It was in this city that they both lived in a modest apartment, one a widow and the other fatherless at the age of ten. Maria Eugénia, in the frailty of her 97 years, is the embodiment of humility and of a dream never lost, as she asserts that “Angola is a great country, I believe it has the potential to give all its children a proper life” (M. d. Cruz 2024).

Bibliography

Barradas, Ana. As clandestinas. Lisboa: Ela por Ela, 2004.

BUALA. Sarah Maldoror, a poesia da imagem resistente. 1 September 2021. https://www.buala.org/pt/afroscreen/sarah-maldoror-a-poesia-da-image (acessed in 31 January 2025).

Cruz, Maria Eugénia Leite Nunes da, interview by Paulo Lara. Luanda, (31 July 2010).

Cruz, Marília da, interview by Aida Gomes. (November 2024).

Garcia, Susana. ““A mulher é o único receptáculo que ainda nos resta, onde vazar o nosso idealismo.” – Goethe.” Tribuna das Ilhas, June 2014.

Lara, Lúcio. “Um amplo movimento: Itinerário do MPLA através de documentos de Lúcio Lara (1961-1962).” 2006.

Paredes, Margarida. Combater Duas Vezes: Mulheres na luta armada em Angola. Verso da História, 2015.

—. “Deolinda Rodrigues, da família metodista à família MPLA, o papel da cultura na politica.” 2011: 10-26.

Rocha, Beatriz Sousa. “As representações da rainha Nzinga.” Atas dos Encontros da Primavera 2021, 2022: 229-252.

Rocha, Edmundo; Soares, Francisco; Fernandes, Moisés (Coord.). Viriato da Cruz: O homem e o mito. Luanda: Chá de Caxinde, 2008.

Rocha, Edmundo. “Viriato da Cruz: O rosto político do grande poeta político.” Afro-Letras, Revista de Artes, Letras e Ideias, March 1999.

Rodrigues, Deolinda. Diário de um exílio sem regresso. Luanda: Nzila, 2003.

Santiago, Onélio. “Viriato da Cruz agraciado com a mais importante distinção do Estado: Um prêmio com sabor a redenção.” Nova Gazeta, November 2018.

Tolan-Szkilnik, Paraska. “Maghreb Noir: The Militant-Artists of North Africa and the Struggle for a Pan-African, Post-Colonial Future.” Jadaliyya, 2023.

Torres, Adelino. Prefácio livro: DÁSKALOS, S. “Um testemunho para Angola: do Huambo ao Huambo.” Vega 2000, 1998.