Union Jacking. The voice of the voiceless

Yonamine was born in Angola in 1975. After growing up between Zaire (R.D.C.), Brazil and the United Kingdom, he now lives and works primarily in Harare, splitting the rest of his time between Luanda, Lisbon and Berlin. His influences come from every corner of contemporary art and music spheres. Prolific and unexpected, Yonamine’s paintings, as much as his assemblages, collages, performances, graphics, moving images and assertive spoken words resonate with the contemporary world culture in a moment where “Post-colonial discussions have never been so often evoked by its Siamese twin: the colonizer”1, as Okwui Enwesor said. As in post-colonial discussions where it is crucial to understand the history in order to follow, with Yonamine’s work it is essential to acknowledge the background issues informing his artistic practice to understand the contemporary discourse presented in each new exhibition.

Yonamine, Union Jacking, The Voice of the Voice£ess, Gallery Cristina Guerra, Lisbon, images Vasco Stocker Vilhena

Yonamine, Union Jacking, The Voice of the Voice£ess, Gallery Cristina Guerra, Lisbon, images Vasco Stocker Vilhena Yonamine, Union Jacking, The Voice of the Voice£ess, Gallery Cristina Guerra, Lisbon, images Vasco Stocker Vilhena

Yonamine, Union Jacking, The Voice of the Voice£ess, Gallery Cristina Guerra, Lisbon, images Vasco Stocker Vilhena

In this fourth solo exhibition at Cristina Guerra Contemporary Art, Yonamine presents one installation “Xplicit Robbery” that occupies the entrance of the gallery space, a work that speaks about the “banality of power” in our time. Driven by “white supremacism” ideologies, the abuse of power has been dominant throughout the colonial period, including apartheid. Nowadays these practices continue and prevail against several individuals, including Mumia Abu-Jamal2, still in jail.

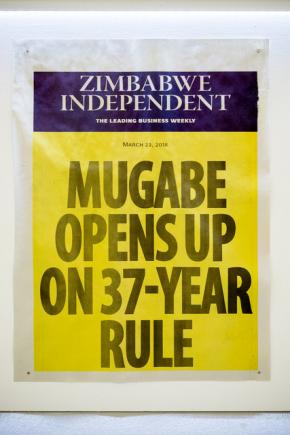

In analogy with the constant buzz of the suppressed voices in this world, we are welcomed to the gallery space by the sound of recorded real time bees, a piece called “Like a Bee”. As in a police investigation where walls are filled with evidential material pinpointing the guilty ones, Yonamine has theatrically composed the gallery walls with posters made out of a selection of articles from Zimbabwean newspapers (dating from 1989 till now), paintings and video animations, showing several graphic references of power such as Napoleon figure and the Ku Kux Klan uniform presented in a navy blue adulterated version color that evokes the uniforms of Zimbabwe’s workers. All these elements are presented as political propaganda in the eve of an election, personifying the conqueror’s evil thirst to reach power and control by keeping the opposition voiceless. Corruption being the determinating factor of this dynamic, as we can witness in the thirteen framed posters “Real Life Drama”.

Achile Mbembe mentions this control in his eponymous publication “On the Postcolony” (2001)3, a reinterpretation of the complexity of expressions such as violence, wonder and laughter, as described earlier by Ngūgī Wa Thiong’o4: “Economic and political control can never be complete or effective without mental control. To control a people’s culture is to control their tools of self-definition in relationship to others. For colonialism this involved two aspects of the same process: the destruction or the deliberate undervaluing of a people’s culture, their art, dances, religions, history, geography, education, orature and literature and the conscious language of the colonizer”. The origin of these thinkers—oppressed by the British empire—is imprinted in Yonamine’s new body of work that dismantles the power of the colonizers by defragmenting the Union Flag, one of the main visual symbols of control, remixing it in this complex installation “Xplicit Robbery” which combines visual elements of abusive behaviours, illustrating centuries of dispossession from the people and rape of women in particular5.

Yonamine, Union Jacking, The Voice of the Voice£ess, Gallery Cristina Guerra, Lisbon, images Vasco Stocker Vilhena

Yonamine, Union Jacking, The Voice of the Voice£ess, Gallery Cristina Guerra, Lisbon, images Vasco Stocker Vilhena

This Union Jack is the result of the unity of the flags of the different countries which comprise the United Kingdom: England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. A blue field with the red cross edged in white and a diagonal red cross. These elements are recurrent in the entrance installation and the seven paintings Yonamine is presenting in the gallery crossed over by reflective green and white, pink and white ribbons on the beautiful dark navy-blue canvases titled “Azul Indígena”. The artist is diminishing the Union Jack colors as much as its symbiotic relationship to power. These wrapped royal blue colored paintings are like the poisoned gifts of modernity embraced by the Commonwealth Club, given by the colonizer to the Rhodesian people in exchange for serving on behalf of the United Kingdom during the Second World War against the Axis forces in Italian East Africa. From the Irish to the Igbo or Massaï people, the Empire has ruled and the metanarratives prevail, keeping the guards of Buckingham Palace shining for the tourists and the workers wearing blue clothes, as if nothing happened or changed.

Yonamine, Union Jacking, The Voice of the Voice£ess, Gallery Cristina Guerra, Lisbon, images Vasco Stocker VilhenaZimbabwe began as a colony of the British South African Company in the late 19th Century. Run by the British empire-builder Cecil Rhodes, he initially named the country Southern Rhodesia, only later did it become Zimbabwe. After Southern Rhodesia was annexed by the United Kingdom in the 1920s, a white minority ruled for decades. Eventually in 1965 the government declared independence from Britain, prompted by international sanctions. Years of guerrilla warfare in the bush led to pressure for a negotiated settlement and in 1979 a peace agreement emerged, a new constitution and leader in former guerrilla called Robert Mugabe came soon after. “Mugabe, who ruled the former British colony for nearly four decades, was ousted in November 2017 as part of a military coup. He was succeeded by President Emmerson Mnangagwa, formerly Mugabe’s deputy. Mnangagwa has been trumpeting “Zimbabwe is open for business” a mantra in an attempt to resurrect the nation’s economy, which has been crippled by hyperinflation and sanctions”6.

Yonamine, Union Jacking, The Voice of the Voice£ess, Gallery Cristina Guerra, Lisbon, images Vasco Stocker VilhenaZimbabwe began as a colony of the British South African Company in the late 19th Century. Run by the British empire-builder Cecil Rhodes, he initially named the country Southern Rhodesia, only later did it become Zimbabwe. After Southern Rhodesia was annexed by the United Kingdom in the 1920s, a white minority ruled for decades. Eventually in 1965 the government declared independence from Britain, prompted by international sanctions. Years of guerrilla warfare in the bush led to pressure for a negotiated settlement and in 1979 a peace agreement emerged, a new constitution and leader in former guerrilla called Robert Mugabe came soon after. “Mugabe, who ruled the former British colony for nearly four decades, was ousted in November 2017 as part of a military coup. He was succeeded by President Emmerson Mnangagwa, formerly Mugabe’s deputy. Mnangagwa has been trumpeting “Zimbabwe is open for business” a mantra in an attempt to resurrect the nation’s economy, which has been crippled by hyperinflation and sanctions”6.

As in many other African countries, “banality of power” continues today in Zimbabwe, infiltrated by wild capitalism such as the Chinese trade invading local markets and dispossessing local businesses like local safety matches factory Lion or Sim Oil are running down in Harare. Yonamine uses their corporate image along the German Rot and Weiss inscriptions inserted in the paintings. The dream of “modernity” is still appealing: as we can see in the video animation titled “Tree Cutting Specialists” refers to the cutting of the precious trees of Mother African and the idea of massive factories working still in the minds as just surviving is such a struggle. When one starts to read about Zimbabwe, one keeps travelling through different narratives of predations, pillaging and dispossessing people, as if only picking the eggs results impossible. As the artist says, “No more eggs, just the empty containers as an analogy to the extinction of the bees and of the African soul”. In both works “Like a Bee” and “Ovos dourados” are analogies of the everyday struggles to activate mike bees, round and round in circles, sound threatening to illustrate the harshness of the real life in Africa.

Yonamine, Union Jacking, The Voice of the Voice£ess, Gallery Cristina Guerra, Lisbon, images Vasco Stocker VilhenaThe control of the people is still going on. Religions and sects know how to handle their church pastor known as “Madzibaba”, the eponym title of the artist video work, reminding us of the vicious circle of life always renewed by its younger generations. The youngsters are revealing their vulnerability by following the same avenue of an Africa taken care by women, where men repeat the mistakes of the past and where corruption regardless of their flag color or religion mix. Yonamine aims at what Paul Gilroy, one of the most incisive thinkers of his generation wrote about in his book, “Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack”, to “show how the history of British racism is bound up with an imaginary English ‘national culture’, supposedly homogenous in its whiteness and Christianity.

Yonamine, Union Jacking, The Voice of the Voice£ess, Gallery Cristina Guerra, Lisbon, images Vasco Stocker VilhenaThe control of the people is still going on. Religions and sects know how to handle their church pastor known as “Madzibaba”, the eponym title of the artist video work, reminding us of the vicious circle of life always renewed by its younger generations. The youngsters are revealing their vulnerability by following the same avenue of an Africa taken care by women, where men repeat the mistakes of the past and where corruption regardless of their flag color or religion mix. Yonamine aims at what Paul Gilroy, one of the most incisive thinkers of his generation wrote about in his book, “Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack”, to “show how the history of British racism is bound up with an imaginary English ‘national culture’, supposedly homogenous in its whiteness and Christianity.

Yonamine, Union Jacking, The Voice of the Voice£ess, Gallery Cristina Guerra, Lisbon, images Vasco Stocker Vilhena

Yonamine, Union Jacking, The Voice of the Voice£ess, Gallery Cristina Guerra, Lisbon, images Vasco Stocker Vilhena

- 1. ‘Inclusion/Exclusion: Art in the Age of Global Migration and Postcolonialism”, Okwui Enwezor, Frieze, n°33, 1997, cited in the introduction of Koyo Kouoh catalogue “Still (the) Barbarians”, EVA2016, Limerick, Ir.

- 2. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mumia_Abu-Jamal

- 3. Achile Mbembe, 2001, UC Press edition

- 4. “Decolonising the Mind “, Ngūgī Wa Thiong’o, 1986, p. 16, ed. James Currey/Heinemann, Isbn 0-85255-501-6

- 5. « Le Ventre des Femmes », Françoise Vergès, 2018, p. 179, ed. Albin Michel Isbn 978 2226 395252

- 6. en.wikipedia.org/wik/History_of_Zimbabwe