Cold sweats and furtive listening in Angola

During the 1960s and early 1970s, both the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and the National Front for the Liberation of Angola (FNLA) regularly transmitted radio broadcasts into Angola from their positions in exile. Angolans—most of whom lived under the repressive authority of the colonial Portuguese state—tuned their radio sets to receive these illegal broadcasts.

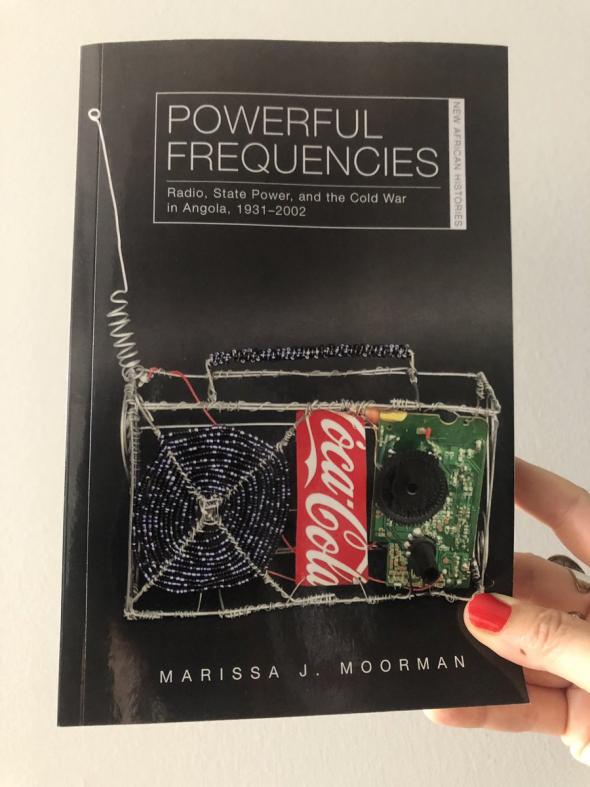

As historian Marissa Moorman describes in her book, Powerful Frequencies: Radio, State Power, and the Cold War, 1931-2002, Angolans who listened to guerilla broadcasts planned out their radio listening with care. Furtive listening demanded preparation. Manuel Faria described driving his car into the middle of a soccer field, and only tuning in once the surrounding dark void made him feel secure. A teenaged Ruth Mendes listened to Angola Combatente with her friends in constant fear of getting caught by adults. Other Angolans remembered catching their parents listening in secret, volume turned low, worried that their children would hear too much. In these recollections, Moorman encounters radio consumption as a corporeal, encompassing experience. Angolans who tuned in illegal broadcasts on their radios broke into cold nervous sweats. They fretted about getting caught—by the police, by their parents, by their children—and yet they persisted in listening because they connected with the content. At the same time, the continued broadcasts worried a colonial state that often failed to control transmissions. One can picture members of the International Police for the Defense of the State (PIDE) agonizing as they listened, wondering who else in Angola had tuned in.

What does a cold sweat reveal about the history of radio? How can the discomfort of a nervous stomach and the sensation of clammy palms tell us something new about the practice of modern politics?

When assessed as technological practices—meaning practices based on the application of technical skills—radio broadcasting and modern statecraft share remarkably similar historical trajectories. During the 20th century, effective broadcasts and modern states mutually expressed power by accessing the emotions and perceptions of populations that fell within their range. Radio and statecraft emerged as technologies that could permeate people’s senses of self. As Moorman writes, “[t]echnologies do not determine outcomes, but how they operate has material consequences” (p.69).

Like modern state power, radio technology manifested itself within people’s senses. By noting this, Moorman effectively grapples with and answers one of the most fundamental but also fundamentally complicated historical questions: what is a state? For Moorman, the answer is a layered one, and is best accessed by unpacking a genealogy of radio in Angola. As she describes it, the modern state in Angola (like the country’s radio broadcasts) coalesced in the second half of the 20th century by attempting to stake itself as a useful technology for producing categories of belonging, exclusion, and dissent. Radio producers and listeners invariably understood these insights before state leaders did. Indeed, the first private radio clubs formed in the 1930s provided an outlet for Portuguese settlers to produce their distinctive white identities. The first state sponsored radio stations only emerged in the 1960s as a component of the larger counterinsurgency and military struggle led by a waning colonial state.

As Moorman demonstrates in Powerful Frequencies, the history of radio and of state power are inseparable. She realizes that Angolans perceived the state (and the radio) with all of their senses on high alert. Powerful Frequencies carefully captures the full sensory experiences that overlapped as radio broadcasting and state power expanded and were redefined in colonial and post-colonial Angola. Readers who start this book seeking an aural experience will quickly realize that Moorman draws together so many additional forms of perception. Radio existed in 20th century Angola as a truly broad technology: it contained aesthetic foundations (building edifices, carefully designed studio spaces, advertisements); it touched nervous systems (of individuals and states); it invoked emotion (fear, pride, participation, anxiety); it physically moved (with armies, frequencies, blocked/jammed signals); and it articulated competing intellectual projects (broadcast content, state surveillance).

It would be possible to read Powerful Frequencies as a straightforward history of radio content in 20th century Angola. Likewise, one could also read Powerful Frequencies to a gain a separate, nuanced, view of Angola’s complex political history. Moorman carefully escorts readers through the major events in Angola’s recent past. Those who presented content over the airwaves, who tuned in broadcasts, who attempted to block rival signals, and who communicated jammed content to friends and comrades all formed an essential place in Angola’s dynamic politics.

Separately, these detailed histories of radio and politics in Angola would make this book well worth reading. Yet, Moorman’s book accomplishes something altogether more ambitious. Throughout the book, she doesn’t just represent radio content as a particular kind of historical text (think broadcast transcripts, playlists, program schedules), nor does she merely ask how and why listeners consumed and used certain broadcasts. Instead, Moorman thinks broadly about radio as a very particular kind of modern technology, one whose techniques closely overlapped—often in disquieting ways—with the techniques of modern state power.

Within Moorman’s evaluation of radio, we find out that radio must also be thought of as an affective, not just as an effective technology. Yes, radio is effective in reaching people over broad areas, in sharing news and information, and in inculcating ideas and practices of national identity. But radio also permeates our very sense of being. Even as listeners consumed radio in Angola, they were also often consumed—in body and mind—by radio technology. What does this mean?

In Powerful Frequencies, Moorman demonstrates that radio works as a technology because it acts on and through us. When we turn the dial off on a radio set, the transmission never ends. Radio waves, while imperceptible, continuously flow. Content just heard continues to circulate—within the psyche of people who listened, and again when listeners share with others what they just heard. Modern states often attempt to gain the same forms of influence.

Moorman allows us to see the history of states at the intersection of so many different projections, desires, experiences, conflicts, and creative works. She refuses to rely on a single framework to tell this history—this is not just about how “ordinary people” (in the classic social history formation) encountered the state, or how government elites implemented their authority. Rather, she fleshes out statecraft as an encompassing and ever changing set of existences.

In the introduction to Radio Benjamin, a collection of Walter Benjamin’s radio broadcast transcripts from 1927 to 1933, Lecia Rosenthal writes: “How do we define the shifting boundaries of the radio work—as historical event and surviving text, singular performance and reproducible artifact, live broadcast and published material?” How, in other words, do we capture and critique something that is simultaneously temporary and permanent? In Powerful Frequencies, Moorman meticulously replies to this problem through a close reading of the history of radio in Angola. In Moorman’s analysis, radio does not just exist for its content, it exists as a particular type of modern technology whose very power stems from its capacity to act (and be acted on) by its audiences.

Only radio receivers can feel radio waves. But people feel radio. Radio, Moorman reminds us, courses through our lives everywhere we go and alongside everything we do. And in many regards this is what modern statecraft is like. It envelopes us in ways that are often beyond immediate perception. Powerful Frequencies tells us how and why we need to finely tune our receivers, to attend to these ranging forms of power, and to hopefully—like the Angolans that have listened so carefully—find new ways to innovate and protest.

Article originally published in Africa is a Country.