Hair as Freedom

“Fusca sum et formosa – I am dark and beautiful” declares the legendary Queen of Sheba in early translations of the Old Testament. The King James translation of the Bible, issued in 1611 as Europeans were getting embroiled in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, transformed this phrase into an apologetic “I am black, but comely”.

In 2019, 25-year-old South African, Zozibini Tunzi, made history by becoming the sixth Black Miss Universe and the first ever to sport natural African hair. Ms Tunzi had discarded weaves to go natural for the Miss South Africa contest held a few months earlier. It was unnerving for her: “Before going natural I was scared of not being beautiful because of the misconception I had of what beauty is, mainly because beauty was never presented to me as someone who has my kind of hair,” she posted on social media a few days before the pageant.

After being crowned Miss South Africa, in the months leading up to the Miss Universe contest, Tunzi, now well aware of the symbolic value of her natural style to young girls, resisted pressure from people urging her to wear a weave. “I feel beautiful in my short, afro hair,” she said. “This is how it grows out of my head … and I wanted the world to see it like that.” While she garnered plenty of praise for her choice – which should be trivial, but is a bold one in the global arena of beauty – she also drew criticism. Social media detractors disparaged her for being “underwhelming” and a “downgrade” without flowing locks. Ms. Tunzi was declaring to the world that she was black and beautiful; her detractors wanted her to show that she was black, but beautiful.

Image credit Yarri Kamara

Image credit Yarri Kamara

Four hundred years after the institution of slavery set off mechanisms devaluing African aesthetics, many on the continent still have a difficult relationship with African women’s hair. Granted, the natural hair movement has gathered momentum in African countries in the past five years, following earlier trends in the US and Europe. Many more young women today wear natural styles unapologetically just like Ms. Universe 2019. Yet resistance to natural hair, in particular afros and dreadlocks, persists. And there is still an immense appetite for styles that mimic Western aesthetics. Hair weaves in particular, since the 2000s have become ubiquitous in Africa, having helped to bump relaxers off their 1990s throne. Many weave-wearers are just as unapologetic in their weave-wearing as the naturalistas are. Wearing a weave, they claim, is nothing more than a personal aesthetic choice. Given the history of degradation of African hair, particularly in its tightly-coiled variant, is this position tenable?

*

Looking back in time

The Sankofa bird reminds us that: to know where you are going, you need to know where you came from. So, let’s go back in time to one of the most disruptive events for the African’s self-image – the slave trade. Let us understand what hair was then, and put it into perspective, vis-à-vis what it is now. Hair has been serious business in Africa for a long time. The sociological value of hair stems from the fact that it is public, biological yet modifiable: all societies manipulate hair to function as a signifier. This function was particularly strong in pre-colonial African cultures – hairstyles were used to communicate ethnicity, clan, social status or life events. 16th-century travellers to the West African coast were struck by the elaborate intricacy and variety of hairstyles. Plaited and braided styles, along with shaved patterned hair were the norm in many African regions. Sometimes hair was rolled with mud to form lock-like styles or sculpted into commanding forms. Barring a few exceptions, mainly in Eastern Africa, hair was not simply combed out. The practice of adding extensions to hair was common. In some cases, as in the Wambo women in present-day Namibia with their ankle-length braids, attachments came from non-hair organic matter. In other cases, it came from hair shorn from the heads of others. Thus Quaqua women in present-day Cote d’Ivoire reportedly donated hair to their men who styled it into long braided attachments.

Early accounts of African hairstyles do not often mention head coverings – caps or headwraps – and do so more often for men than women. However, the uniform adoption of headwraps among all African diaspora populations, whether in Latin America, the Caribbean or North America, suggests that head-wrapping was entrenched in the continent, at least in West Africa whence most slaves were taken, before or during the course of the slave trade. Historian Helen Griebel highlights how Black slaves in America folded fabric into rectilinear shapes tying knots high up on the crown of the head, a uniquely Afro-centric fashion that leaves forehead and neck exposed, enhancing facial features. Euro-American head-wrapping by contrast uses a triangle fold and is always fastened either under the chin or at the nape of the neck, visually flattening the face. In addition, headwraps in some places were used as signifiers – in Dominica for instance peaks in the headwraps would represent women’s relationship status – echoing practices in Africa. What is clear is that by the 20th century, headwraps were popular in many African cultures. In Mali, Senegal and Nigeria, in particular, headwraps were an expression of femininity and were tied in several ways to communicate social status. In southern Africa, women wore headwraps, called doeks or dhukus, as a sign of humility for occasions such as meeting the in-laws.

The forced migration of African populations to the Americas set in motion a bi-directional flow of influence between Old Africa and its diaspora. Newly arrived slaves perpetuated certain African hair practices – plaits and headwraps – as a way of reaffirming their humanity and their identity. Headwraps are an interesting illustration of the bi-directionality of these flows. Slaves in the US initially spontaneously wore headwraps. However, in Louisiana in 1786, they were forced to by law. The Tignon Law was established to rein in the social climbing of attractive Black and biracial women. All Black (by the American definition) women, whether free or slaves, were henceforth to cover their hair, as a marker of their inferior status to white women. Black women responded by transforming the headwraps into elaborate works of coquetry. After emancipation, the headwrap came to be considered rural and backward by Black Americans eager to shed off reminders of life in shackles. However, in the 1960s, as Black Americans sought to affirm their unique identity during the civil rights movement, headwraps made a come-back, influenced in part this time by Nigerian gélés. And styles spawned in the Americas, like the Nefertiti-style headwrap favoured by jazz singer Nina Simone, found their way back to Africa.

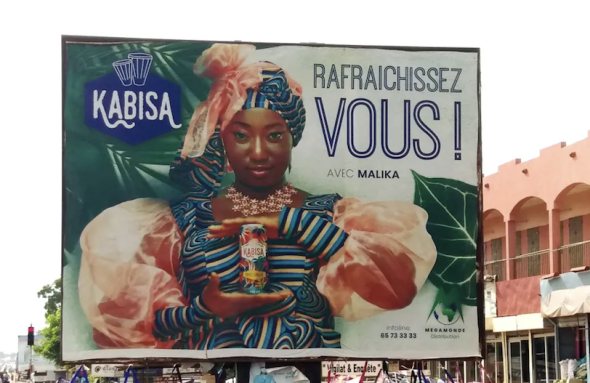

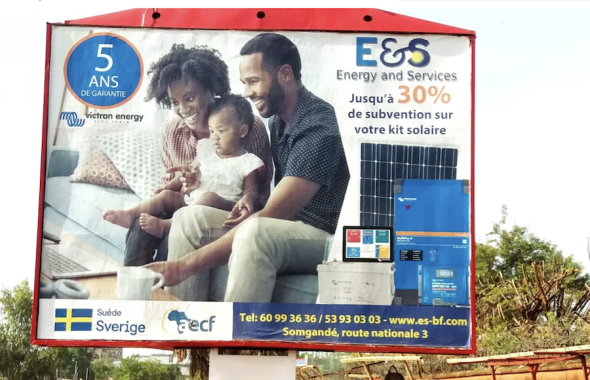

A billboard in Oagadougou. Image credit Yarri Kamara

A billboard in Oagadougou. Image credit Yarri Kamara

Hair practices forged under the assault of white supremacy of the slave plantation also found their way back to the Old Continent. Under the institution of slavery, African “woolly”, “matted” and “kinky” hair was constantly denigrated, and considered incompatible with any standard of beauty, and particularly feminine beauty. The slave plantation inflicted a white aesthetic on Black people. The lighter your skin and the straighter your hair, the better chances you had of gaining privileges within, and also outside of, plantation life. In slave-economy USA, hair straightening was regularly practiced by Black people from the 1800s. Early methods included ironing hair and pulling hair. Pressure to conform to white aesthetics mounted after emancipation as Black people sought paid employment and more ambitious social status. Straightening techniques were revolutionised at the beginning of the 1900s when Black women entrepreneurs, who became hair millionaires, invented hair straightening systems, involving creams and hot-combs. Interestingly, one of the hair pioneers, Madame C.J. Walker, as she called herself, claimed that her special formula came to her in a dream in which a big Black man explained which ingredients she had to source from Africa.

Right from the get-go, hair straightening elicited heated debate in the Black American community. In Hair Story, Ayana Byrd and Lori Tharps cite a 1904 article titled ‘Not Color but Character’ in which a Black educator of girls impassionedly charges: “What every woman who…straightens out needs, is not her appearance changed but her mind changed…If Negro women would use half the time they spend on trying to get white, to get better, the race would move forward.” Marcus Garvey later echoed this sentiment in his slogan: “Don’t remove the kinks from your hair! Remove them from your brain!” The practice was considered so contrary to the emancipatory ethos of the time that businesses selling products for straightening hair were initially banned from the National Negro Business League. Regardless, the compulsion to straighten hair was strong. Even Malcolm X succumbed to the practice before becoming the iconic Black freedom fighter he later was. In his autobiography he relates how he burned his scalp to achieve what was called a “conk” at the time:

My first view in the mirror blotted out the hurting. I’d seen some pretty conks, but when it’s the first time on your own head, the transformation after a lifetime of kinks, is staggering…On top of my head was this thick, smooth sheen of red hair … as straight as any white man’s.”

When a chemist found a formula for turning wool into imitation fur in 1947, the chemical relaxer was born, and hair straightening took off even more in the US. In 1950, the first weave was also patented in the US, giving Black women another option for achieving white hair aesthetics.

Africans on the continent faced some of the same pejorative deprecation of their hair as their counterparts in the Americas did, but with less immediacy. Black Africans were by far the majority on the continent and not all Black people were regularly confronted with white aesthetics. Moreover, the circulation of imagery through mass communication was still limited during most of the colonial period. Nonetheless some urban elites, and especially those in white settler colonies, may have faced high levels of denigration of their former hair styles. Photo archival material, on the other hand, suggests that rural women across Africa, largely continued to pursue their own hair aesthetics. Meanwhile, photos of urban African women prior to the 1960s show a few straightened styles, but mostly headwraps, plaited styles and afros. Hair straightening, carried out with hot combs at the time, was accessible only to the richer women, and to some extent became a marker of class. The return to natural hair represented by the 1960s and 1970s afro, was mainly perceived as an American style and took on its signifier of liberation from the US civil rights movement. When the afro died out in the US in the 1980s, replaced by the Jheri curl and other heavily processed styles, it also dwindled out in Africa.

In the 1970s, cheaper chemical relaxers arriving on the continent made hair straightening more widely accessible. The practice was likely perceived both as a way of achieving the hegemonic white ideal aesthetic, and as a way of being modern by emulating popular Black American stars. Richer African women could also achieve their desired modernity with wigs or weaves, but these remained cumbersome and expensive until the 1990s. With the exception of Mobutu’s Zaire which banned hair straightening and wigs, along with other Western fashions, few accounts of the time note particularly strong African opposition to the practice.

While plaited styles, braids and headwraps continued to be worn by women from all classes in post-independence Africa, by the 1990s, urban elites overwhelmingly adopted a Western aesthetic of straightened hair, and this trend would remain entrenched until the 2010s.

Image credit Yarri Kamara

Image credit Yarri Kamara

*

Where are we now?

There is a growing body of critical examinations of African women’s relationship with hair that often chronicle personal hair journeys. There are however few studies that give a picture of just what Black African women are doing with their hair today. In early 2021, I sat down in markets, in banks, in posh restaurants, in popular picnic areas and in health clinics to observe the hairstyles of 425 Black African women in Ouagadougou to get some figures to work with.

I divided hairstyles into five categories: natural, that is hair that has not been chemically treated, whether it was combed out, in dreadlocks, or plaited without long extensions; braids, that is hair plaited with long extensions; headwraps, irrespective of whether hair under the wrap was natural or chemically treated; weaves; and chemically relaxed hair. I excluded women wearing religious veils from the sample. My fundamental interest being in the cultural aesthetics the hairstyles represented, I then split the categories into two aesthetic groups. The first three categories are considered as emanating from African aesthetics. Women who wear braids or headwraps may have unprocessed hair, as they may have relaxed hair, but they have chosen at that moment in time to follow an African aesthetic. Weaves that mimicked coiled African hair (but not loose curls often associated with biracial Black hair – this will be clarified below) were categorised in the natural hair category, as were braids that resemble dreadlocks, as these styles are adopting a natural African aesthetic.

Eurocentric weaves, regardless of the state of the hair under the weave, and relaxed hair on the other hand were considered as emanating from a Western ideal aesthetic. Weaves mimicking loose curls typical of many, not all, biracial Blacks were included under this aesthetic. Slave plantations and colonialism gave rise not only to an ideal of white beauty, but also – as the second best thing – of biracial beauty. Ivorian journalist Serge Bile’s inquiry into the motives for bleaching skin is illuminating on this point: many respondents plainly indicated they wanted to look biracial. In the Americas, and later in Africa, biracial women were more frequently considered to have “good” hair. While in the past even this “good” hair may have been subjected to straightening just like “stubborn” hair, increasingly today the biracial-type loose curl is becoming a new ideal standard.

What did my observations find? Braids are the most popular hairstyle among Black African women in Ouagadougou (33%), followed by weaves (25%), headwraps (21%), natural-look styles (16%) and finally relaxed hair, worn by only 5% of women. When categorised according to aesthetics we have about two-thirds of women opting for African aesthetics and one-third for Western aesthetics. Burkina Faso, as other West African countries, may not be reflective of the rest of Africa as it may be that African aesthetics generally have persisted more strongly in West Africa than in other regions of Africa.

I, therefore, sat and looked at a bunch of photos of international conferences and workshops held in capitals in all regions of sub-Saharan Africa between 2018 and early 2020. The Burkina Faso sample covered women of all categories in Ouagadougou, from market women on bicycles to patrons at exclusive restaurants; this extended sample, on the other hand, focused on women of the African intellectual elite – scholars and functionaries in international organisations. Given the difficulty of distinguishing between weaves and relaxed hair in photos, these categories were combined and accounted for 45% of the 180 women observed. Headwraps were much less prevalent in this whole of Africa sample (only 10% of women). Braids and natural-look styles accounted for 23% and 22% of women respectively. Thus when the rest of sub-Saharan Africa is considered – at least for elite women - the ratio of African versus Western aesthetics shifts to roughly fifty-fifty. Casual observation of popular African music videos would tilt ratios largely in the favour of Western aesthetics, and almost exclusively towards long weaves, for videos by male musicians.

Headwraps warrant a little more discussion. In Burkina Faso, this style was particularly observed among lower class women and older women. Many older women holding elite positions in government and public institutions regularly wear headwraps in West Africa; the newly appointed head of the World Trade Organization, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala is a prominent example. This headwrapping follows different codes from headwraps in the African diaspora and other African regions where headwraps may be seen as youthful or informal. The debate around whether headwraps were appropriate for television after a reporter wore one on South African eNCA channel in 2016, would not occur in West Africa. Headwraps, while an aesthetic expression, are sometimes also worn for practical purposes of covering hair that is in the process of being styled. Increasingly, it is also a practical way for women to cover up hair loss – sometimes due to over-processing.

*

Natural hair and weaves face off

The data from my observations confirm that today there is a perceptible shift towards styles with a natural or African aesthetic. But at the same time there is also a strong presence of weaves, which have taken up the ground lost by chemical relaxers. The same trend is observed in the US: the natural hair movement among Black Americans exploded in the late 2000s, while the imports of weaves from China and India also grew to unprecedented heights. So, we have two apparently contrasting trends, one that enthusiasts sometimes portray as moving towards “authenticity”, and the other, that detractors characterise as embracing “artificiality”. To better understand what these two trends mean for African society, let us examine the resistance to each one of these trends.

Much has been written elsewhere on resistance from non-Africans to natural hair, and here we will focus on African perceptions. The negative reactions to Miss South Africa’s 2019 win make it clear that natural hair is problematic for some. A Miss South Africa without long and flowing locks was just not sophisticated enough, just not beautiful enough. The yardstick of white aesthetic standards certainly plays a role, but some forms of resistance may also be linked to local aesthetics. African resistance rarely targets plaited and braided styles, but most often large afros and dreadlocks. Few African cultures had a historic practice of wearing hair long and combed out. The modern afro was in most cultures an intermediate step while styling hair into something more structured. For an older generation, this bias may remain and is elicited more strongly by the deliberately messy texture of contemporary afros compared to the carefully groomed afros of the 1960s. Dreadlocks in some cultures were linked to mystical practices that in some cases were revered, in others feared, or at least considered a sign of not being part of conventional society. Asante priests in Ghana, for instance, historically wore their hair matted in long locks that were called mpesempese, literally meaning “I don’t like it”. However, culture and aesthetics are in constant evolution, and these resistances are by no means immutable. Also, as long as resistance remains a question of personal taste, that is fine. When it devolves into the use of institutional norms against the very nature of African hair, we cannot abstract from the violence such resistance represents.

Institutional forms of resistance are often perceived by victims as a prolongation of colonial violence, as they should be. When in 2016, Black students at the exclusive, formerly white Pretoria High School in South Africa were suspended for wearing their hair in “unladylike” afros, afros that had been sported by iconic anti-apartheid figures in the 1950s (and incidentally may have been the original inspiration for Black Panther afros in the US), how else can this be viewed but as an assault? As the school authorities taking the sjambok from former racist occupiers to continue running the relay of the denigration of African biology? And what can we make of a country like Zambia that forbids signs of dreadlocks in official identification photos, not having bothered to change British colonial laws devised against the dreaded dreadlocked Mau Mau freedom fighters in their Kenyan colony?

Image credit Yarri KamaraOn the other hand, resistance to straightened hair in Africa in the past has generally been muted but nonetheless present. Many schools in Africa, as late as the 2010s, forbade girls from wearing relaxed hair or weaves, presumably on grounds of modesty. In some cases, the stricture arose from colonial hygienist practices obliging all girls to wear their hair shorn. Luckily, in many African countries, using relaxers or weaves on girls is generally not considered appropriate before the teenage years, unlike their counterparts in diaspora populations who may get hair relaxed as young as three. More interestingly, relaxed hair and weaves are in some cases proscribed from traditional cultural functions. Ashanti queen mothers in Ghana are obliged to hide their hair if it is not natural during traditional ceremonies. Eurocentric styles have thus been considered incompatible with certain functions linked to traditional African identities and inappropriate for the innocence of youth (although it could also be a monetary issue, as richer Africans are more likely to relax, or today, weave the hair of their children younger).

Image credit Yarri KamaraOn the other hand, resistance to straightened hair in Africa in the past has generally been muted but nonetheless present. Many schools in Africa, as late as the 2010s, forbade girls from wearing relaxed hair or weaves, presumably on grounds of modesty. In some cases, the stricture arose from colonial hygienist practices obliging all girls to wear their hair shorn. Luckily, in many African countries, using relaxers or weaves on girls is generally not considered appropriate before the teenage years, unlike their counterparts in diaspora populations who may get hair relaxed as young as three. More interestingly, relaxed hair and weaves are in some cases proscribed from traditional cultural functions. Ashanti queen mothers in Ghana are obliged to hide their hair if it is not natural during traditional ceremonies. Eurocentric styles have thus been considered incompatible with certain functions linked to traditional African identities and inappropriate for the innocence of youth (although it could also be a monetary issue, as richer Africans are more likely to relax, or today, weave the hair of their children younger).

With the rise of the natural hair movement, opposition to weaves and relaxers has become louder, and some women have felt personally under attack for their hairstyle choice. They take issue in particular with the notion that wearing a weave or relaxed hair is a sign of self-denigration. Several arguments are put forth in defence.

A first line of argument is a semantic attack, aimed at pointing out that natural styles are not so natural or not so African, and therefore no different from altering hair with weaves and relaxers. Let us clarify the semantics therefore. Natural simply means hair that has not been chemically altered (except through hair dyes). It does not mean hair that is not groomed, styled or maintained. In African contexts, where extensions and add-ons have historically been an integral part of coiffures, it also does not necessarily mean that nothing has been attached to the hair. Braided styles with extensions (which today are almost always synthetic) are a very common way of styling chemically untreated hair in Africa. Weaves can also be attached onto chemically unprocessed hair; but if the question of aesthetics is considered, it becomes clear that weaves that bear no resemblance to what natural African hair can do, serve to devalue African hair. Natural also does not mean historically authentic. Cultures and fashions, hair styles included, are in constant evolution; therefore, the fact that a hairstyle – the afro, for instance – has no historic precedent within Africa, does not make it less natural, and does not mean that today it cannot be a sign of pride in African culture.

Another argument is that white women alter their hair just as much as Blacks, wearing wigs, extensions and even straightening their hair. All cultures have always engaged in hair altering practices, and within any community, there are always going to be individuals that seek to emulate another individual’s aesthetic. However, hair-altering among non-Black women almost always involves styles that belong to their cultural and biological aesthetic corpus. A Sicilian who straightens her voluminous curls can be seen as paying homage to her Milanese cousin. A Dutch woman who gets a curly perm to spruce up her lanky hair is perhaps inspired by the curls of her French neighbour. Exceptions either involve hairstyles intended to communicate a position at the margins of society – white rastafarians and punks – or have never been more than short-term fads – Bo Derek braids and 1980s crimped hair. Hair straightening, by contrast, has plagued Black people since the 1800s.

Then there is a body of arguments aimed at delinking the choice to wear Eurocentric styles from issues of identity. Weaves or relaxers are put forward as a choice of convenience: it is much easier to manage hair when it is false or straight. Others argue it is not really a case of wanting to look white, but rather following standards that media and advertisements feed African women. Or that some professional settings impose these styles: you cannot get ahead professionally with natural styles. Or that men want women with long hair. Others say simply this is my personal aesthetic choice, this is how I feel beautiful, or for those who like frequent changes of hairstyles, this is how I feel creative.

One exasperated woman in a 2015 BBC feature on African hair exclaims: “The idea that when a Black person wears a weave it’s a sign of how insecure she is, is just ridiculous frankly. I treat my hair the same way I treat my nails. I can wear it in many different ways – that doesn’t change who I am.”

These arguments all have one fundamental weakness; they are superficial. Scratch beneath their surface and you will find lying under them the valuing of white aesthetics over African aesthetics, integral to the Atlantic slave trade. Let’s take the convenience argument. Hair styling is a craft, all crafts need practice and instruments. Most hairdressers and women in Africa today, due to lack of practice, know better how to care for weaves and relaxed hair than natural hair. Hair product innovation for the past decades in Africa has also neglected natural hair textures – fortunately this is changing. The devaluing of African hair – which was often couched in the terms “unmanageable”, “coarse” and “tough” – has therefore contributed to making African hair inconvenient. Convenience is also a matter of perspective. 50 Ghanaian women responding to a survey by business student Sena Can-Tamakloe in 2011 overwhelmingly said they would encourage their peers to go natural because it is low-maintenance and cheaper. Remember the prevalence of braided styles in Africa. Indeed, to a woman who spends 45 minutes getting her natural hair plaited and decorated with fetching metal ornaments and then forgets about her hair for two weeks, the daily requirements of relaxed hair would seem much more inconvenient. Weaves, admittedly, can be exceptionally convenient, which partly explains their great popularity.

As for following media diktats, professional standards, or what men desire rather than Eurocentric ideals, it does not take much scratching to understand that these institutions or individuals are just re-emitting white standards that have become entrenched in African societies. Media and advertising valorise what a society valorises, sometimes before society, sometimes after. If African women start valuing their natural hair, media images will follow. Thankfully this is already happening. Billboards on Ouagadougou’s roads, while often featuring women with some form of straight or biracial curly hair, also feature women with braided hair, afros and headwraps.

“It doesn’t change who I am,” says the exasperated weave lover from the BBC interview. “It may not, but it changes what your society is, which in turn can shape others around you,” is what we respond to her. Frantz Fanon, who was a psychiatrist by training, in his landmark 1952 book on racism, Black Skin, White Masks puts forth the idea of sociogenics in the study of individual choices. The alienation – and therefore the de-alienation – of Blacks within a racist structure is not just a question of individual choice, he explains. It is also shaped by Black societies, which in turn are shaped by individual choices. The more women there are wearing weaves and relaxed hair - out of free choice or because they feel constrained to do so by any range of pressures - the more African societies integrate the message that a foreign aesthetic is better and deny the value of African textured hair. By consequence more girls grow up feeling inferior due to their tightly coiled hair. More African women place themselves apologetically on the world stage, scared to be rejected and mocked for a part of their biology. It is a personal choice therefore that perpetuates denigration of Africans, creating obstacles for other women to self-actualise without spending energy on fighting stigma around a biological fact that is hair. It is a personal choice that abstracts from historical and contemporary pressures to be other than oneself. It is a personal choice that enslaves others.

*

Hair economics

There are also economic implications. Studies and anecdotal evidence from the US suggest that Black women there spend considerably more money and time on hair care than their non-Black counterparts. The comparative aspect is of interest for appreciating what the opportunity cost of hair is in contemporary society. More money and time spent on hair may mean less of those limited resources available to spend on other things. The wives of Mossi chiefs in Burkina Faso traditionally were expected to shave their heads; perhaps as a sign that they would have more important things to do for their societies than spend time grooming their hair. Different epochs and different classes have dedicated varying amounts of time to grooming. Elite whites in the 1800s would spend inordinate amounts of time on their hair: American Southern belles amidst the humidity of New Orleans kept their Black hairdressers occupied for hours each day. In the contemporary world, there remain few pockets of class that have unlimited leisure time and wealth, and certainly few in view in Africa.

Africa remains a continent with widespread pockets of poverty, despite all the enthusiasm about the rapidly growing middle classes. From this perspective, the size of the hair product market, and particularly the market for weaves, wigs and extensions (dry hair products in industry parlance) is mind-boggling. A 2013 Euromonitor study estimated the African dry hair market at US$6 billion and projected fast growth over the next decade. India and China are the world’s main exporters of human hair and synthetic weaves. While their industries may have started by servicing Euro-American markets (for Caucasians, as well as Blacks), they now have their eyes firmly fixed on the African market where demand is growing fastest. Africa in 2018 accounted for 37% of hair imports from China, a close second after the US, which accounted for 39%. South Africa, Nigeria and Benin were the biggest buyers. The latter imported almost $400 million worth of hair add-ons. Just like it was a hub for African wax cloth imports in the past, Benin appears to be playing an entrepot function here dispatching imported aesthetics to other countries. Beauty industries across the world plague on, and fuel, women’s insecurities everywhere, but Black women represent a reliable jackpot. Shen Dalei, general manager of a weave factory in Xuchang City, China’s wig capital, notes gleefully: “There is rigid demand among Black women”.

Human hair weaves are the premium product among hair add-ons. Nigerian singer Muma Gee in 2014 boasted about her human hair weave that cost upward of $2000. Some hair is collected from Indian temples from women who for religious reasons voluntarily donate their hair. The Tirupati Temple in Andhra Pradesh, one of the biggest such collectors of hair, has made over US$97 million from auctioning off donated hair since 2011. Women in China, on the other hand, tend to sell their hair to collectors. As the human hair business became more lucrative, unsavoury practices crept into the supply chain. There are now reports of children being tricked into having their heads shaved, of husbands forcing wives to sell hair, of hair being harvested from rubbish bins, shower drains and dead bodies. These reports, that a simple Google search will pull up, do not seem to have deterred African consumers. Celebrities continue to spend thousands of dollars and ordinary Africans are willing to spend on average $250 for a single human hair weave.

Synthetic weaves cater to the masses with more modest purses. Some factories make synthetic weaves and extensions for braids within Africa – in South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, Togo and Senegal notably. Most, if not all, of these factories are today owned by Indian or Chinese industrial groups and the raw materials are sourced from Asia. Business blogger John-Paul Iwuoha writing about the tremendous market opportunities in the hair weave business notes that African entrepreneurs are only present at the bottom of the pyramid as importers, wholesalers and retailers. Speaking on the global market for skin bleaching products in Africa in Blanchissez-moi tous ces nègres, Ivorian sociologist Dédy Séri warns: “If you are dominated aesthetically, you will also be dominated economically”.

Now, let’s imagine what this industry could look like if an African aesthetic prevailed in women’s hair choices. Some readers will have negative judgements concerning attaching false (be it human-sourced) hair to your own hair. I suggest you suspend these. As mentioned previously, African traditional coiffures routinely incorporated “falsies”, as did coiffures of Euro-American elite, both women and men, in the 1700 and 1800s, or indeed many traditional Asian styles. So, what would the industry look like? Would there be collectors harvesting hair from Africans blessed with thick luxuriant manes to be processed in African factories making premium extensions and weaves? Remember those Quaqua men who made extensions from their wives’ hair. Would African entrepreneurs have innovated processes for making synthetic Afro-textured hair? Would extensions used for braiding have different textures from those common today?

Recent developments in the liquid hair product market – hair oils, lotions, shampoos – suggest that opportunities indeed have been missed. When relaxed hair reigned, there were few quality hair products made in Africa that an urban elite consumer like myself would have opted for. And few ingredients recognisable as African were in the imported products popular on the market. In Burkina Faso, in the five years since more women have taken to wearing natural styles, several local entrepreneurs have put on the market new quality creams, oils, shampoos and conditioners incorporating shea butter, coconut oil, Chadian chebe powder, hibiscus, okra and other ingredients that you can imagine being grown by African farmers. Returning to natural has liberated African innovative genius and entrepreneurship.

*

What does hair as freedom look like?

Hair as freedom fundamentally means doing away with the notion that African hair as it is biologically textured is abnormal, something to be fought against or hidden. Hair as freedom means seeing African hair as something that can be worn plain or embellished with styles and techniques in harmony with its nature. On a societal level, hair as freedom means making aesthetic choices that build individual and societal self-esteem. Choices that feed local economies rather than generate a frenzy of imports. The rest is up to personal choice.

For some, it will involve spending less time and money on hair, for others it may mean more time and money. The natural hair movement in African diaspora populations tends to promote a model that can be very time-intensive and product-intensive. YouTube tutorials go on about how much time is spent on the infamous “wash day” and all kinds of techniques for stretching hair so that it does not shrink or ensuring you get the juiciest curls. There is a danger lurking in this discourse. From a continental African vantage point, it looks like a white hair beauty standard is simply being replaced with a biracial hair beauty standard. Long and flowing (or at least bouncy) are still the holy grail, it’s just curlier and to be achieved without chemical alteration. Arguably this may be less problematic in diaspora communities where centuries of miscegenation have multiplied the type of hair textures of Black women. (There is plenty in American history that would warn otherwise though – the colour tax applied in the 1920s to fraternity brothers bringing darker dates to events in historically Black colleges, for instance).

On the continent, looser hair textures are largely confined to a few ethnic groups and to people of recent biracial heritage. The latter, moreover, are often (problematically) assimilated to whites. Therefore, African women should not fall into the biracial hair standard trap. Despite the propensity of lazy marketers on the continent to use images from Western photo banks that more often than not feature biracial type hair.

Wearing hair with an African aesthetic can be time-intensive, as it can be time-liberating. The true freedom comes from being able to state with quiet assurance “I am Black and I am beautiful”. No ifs or buts about it.

Written with the support of the Goethe Institut – Residence for Young African Writers

References

BBC News. “Being African: What does hair have to do with it?” 21 July 2015. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-33525254

Bile, Serge. Blanchissez-moi tous ces nègres. Kofiba Editions (2010).

Byrd, Ayana and Lori Tharps. Hair Story: Untangling the roots of Black Hair in America. Revised Edition. St. Martins (2014).

Griebel, Helen Bradley. “The African American woman’s headwrap: Unwinding the symbols.” Dress and identity (1995): 445-460.

Iwuoha, John-Paul. “Human Hair: How this Business Makes Millions of Dollars in African, and the Tricks You did not Know” Smallstarter.com. 1 February 2016. https://www.smallstarter.com/browse-ideas/the-human-hair-business-in-africa-and-how-it-makes-millions-of-dollars/

Liu, Yujing. “Africa’s new-found fondness for hair extension offers cover to Xuchang, China’s hub for wigs and weaves, as US tariffs loom” 25 May 2019. South China Morning Post https://www.scmp.com/business/china-business/article/3011657/chinas-wig-capital-has-designs-africa-us-tariffs-loom

Published originally in Lolwe.