The “war of statues” and the colour of memory

But say, you can go home any time. What I say is, let’s have a look at this glorious nation which we have fought for.

William Faulkner

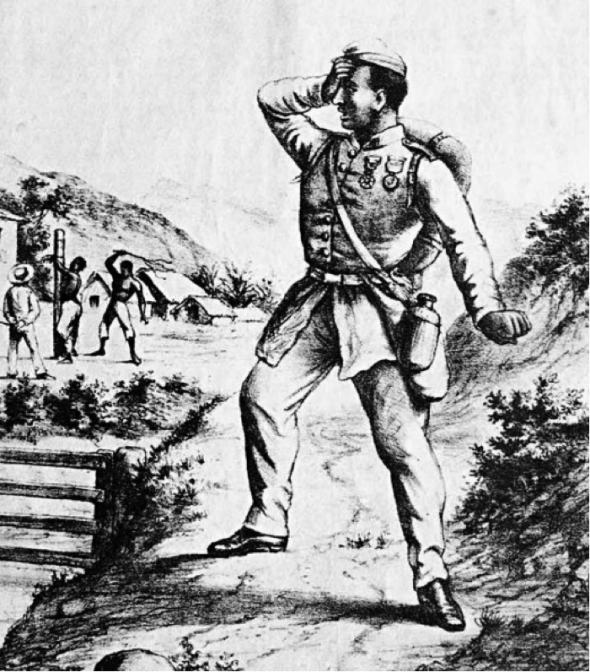

De volta do Paraguai | 1870 | Angelo Agostini

De volta do Paraguai | 1870 | Angelo Agostini

Soldiers’ Pay The “war of statues” has seen an uproar in the United States over the profusion of memorial landscapes which exalt Confederate Generals (the political-military leaders of the Confederate States of America who, between 1861 and 1865, fought for secession in opposition to the abolition of slavery). Places of pilgrimage for far-right groups, the statues of Robert Lee and other generals have come to be denounced by anti-racist movements. They are called out as part of a narrative of “white martyrdom” inscribed in public space since the end of the 19th century (and the so-called Jim Crow Laws). These permanent representations of the past have been decried as insulting and absurd in a place which still lives under the spectre of slavery, lynching and police violence against the black population. Mobilization against the statues, particularly since the murder of Trayvon Martin in 2012, have helped drive the Black Lives Matter movement. These are some of many ongoing disputes in different parts of the world over statues and war heroes – often well-known colonists or slaveocrats – celebrated in public space. It is worth revisiting these disputes from the perspective of the black bodies that have been invisibilized, domesticated and enlisted to defend nations founded on colonial exploitation.

Frank Capra’s 1944 documentary, The Negro Soldier, is a propaganda film made for the American army. It aimed to persuade young African Americans to volunteer in the Second World War. Now available on a popular television platform, The Negro Soldier constitutes a precious memorial of the ambiguity of a certain kind of post-colonial nationalism. Astute and opportunistic, it both recognizes that black men and women had a crucial role in the establishment of the nation, while preserving the idea of the nation as a European construction threatened by the uprising of black bodies who populate, or will come to populate, the homeland.

National war-time mobilization often plays out more or less obvious paradoxes between the consecration of power and symbolism to justify the force of arms, and how the war effort tends to subvert social order. On the one hand we see the exacerbation of nationalisms founded in mythologies which legitimate governing elites and construct the enemy as an insufferable threat. On the other hand, war is a time of exception that, on both the civil and military fronts, grants unprecedented agency to social groups who are otherwise excluded or unrecognized. We are familiar with narratives of how, in particular historical periods, the mobilization of men of military age brings women, disabled and older people to unfamiliar levels of public prominence, whether in local governance, business, hospitals or armament industries. In the same way, wars drive men from motley walks of life to the battlefield: criminals, enslaved people, blacks, indigenous people, ethnic minorities or foreign legions.

Struggling to reconcile the structure of the nation with the convulsions of war, existing powers often declare the end of war as a period of carnival, circumscribing as exceptional the transitory, contrapuntal moment in which those “below” are permitted vain fantasies of belonging and recognition. A caricature by Angelo Agostini, “De volta do Paraguai” [Back from Paraguay], published in Brazil in 1870, incisively portrays one of these returns. Agostini draws a decorated black soldier in uniform, who, on returning home after the Paraguayan War, incredulously sees his mother tied to a tree to be whipped by an overseer1.

Specifically directed at an African American public, The Negro Soldier is an ingenuous exaltation of the participation of black men in various American wars, and an invitation to defend a way of life in opposition to the racist theories of Nazi Germany (the only moment in the film in which slavery is mentioned is to refer to the peoples subjugated by Hitler’s regime). Made in 1944, during racial segregation in the United States, the film exalts black American men and women who are integrated into American society. Its myriad images of pompously dressed African Americans constitute a striking demonstration of the infinite plasticity of the history of black people being put in the service of white mythologies. It would be a supreme fantasy to think, naively, that we can fully recognize the black blood that lies beneath the foundations of nation-empires and post-empires if we also leave in place the very stones that sustain and adorn the idea of the nation.

___________________

MEMOIRS is funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (no. 648624) and is hosted at the Centre for Social Studies (CES), University of Coimbra.

- 1. De volta do Paraguai, lithograph by Angelo Agostini, illustration in the magazine Vida Fluminense, n. 12, June 1870. Fundação Biblioteca Nacional, Rio de Janeiro.