Liberty / Diaspora a universal chronology of the history of decolonization

Perhaps out of secret hope that benevolent forces decide our daily fortunes, we often read coincidences into connections that turn out to have prosaic explanations. I felt touched by one of those tricksy coincidences when, out and about in London, I walked into the Autograph gallery on Rivington Place, and came upon LIBERTY / DIASPORA, an exhibition of the work of Omar Victor Diop.

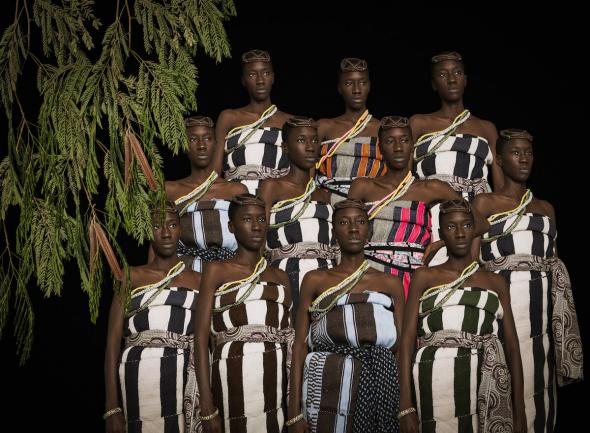

The exhibition is divided into two projects by the Senegalese artist. The first, Liberty: A Universal Chronology of Black Protest, comprises twelve portraits of black figures. Together, these photographs present a possible history of anti-colonial and anti-racist resistance. The chronology they offer is deliberately chaotic and transnational, evoking moments in anti-colonial and antiracist history as distinct as: The Women’s War (1929 in Nigeria); The Railway Workers of Dakar (in 1938 and 1947 in Senegal); The Soweto Rising (in 1976, in South Africa); Selma (1965, in the USA); or The Mutiny of Friedman Field (in 1945, also in the USA).

The second, Project Diaspora, consists of a collection of photographs, almost all reproductions of paintings, of African men who appear in Western histories between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries. We see August Sabac El Cher (1836-1885), an Afro-German soldier who fought in several wars for Prussia; Henrique Dias (1605-1662), renowned for his service to Portugal in the Luso-Dutch War in Brazil; and Frederick Douglass (1818-1895), the celebrated African-American abolitionist leader.

Both projects offer parody rather than any solemn elegy. Their aesthetic is marked, first of all, by the almost narcissistic appearance of Diop himself as a protagonist in most of the exhibition’s images. There is a certain dislocation in this repeated self-portraiture: in Diop’s embodiment of different black characters, he declares the possibility of representing a black man on his own terms, though within extremely Eurocentric matrices of recognition. The assertive, almost arrogant presence and dandy-like quality to the characters portrayed imbue upon Diop’s photographs a humble dignity, an imagined expression of the colonized subjectivity produced by racism.

The Women's War, 1929 | 2017 | Omar Victor Diop, courtesy of the artist and Autograph ABP

The Women's War, 1929 | 2017 | Omar Victor Diop, courtesy of the artist and Autograph ABP

This is the mimicry Homi Bhabha wrote about. The always inappropriate character of the colonial subjects, who fail to identify narcissistically with colonial modes of representation, create an ambivalence that, through a comic and mocking mirror, disturbs the authority of colonial discourse. The football-related props that appear in all the portraits of Project Diaspora add further ambiguity, perhaps because for some black men football today represents a fantastical gateway to the aristocracy of European media culture.

I arrived at Omar Victor Diop’s exhibition during a short visit to London to take part in Decolonizing History: The politics of memory of the Last European Empire, a colloquium organized by Birkbeck College at the University of London. The event, hosted by the historian Luís Trindade, took as its pretext the Portuguese debate about the ‘Museum of the Discoveries’ that Fernando Medina put forward in his election campaign to the Lisbon mayoralty. Among many other things, the Birkbeck colloquium discussed the unsustainability of representing the imperial past in ways that ignore the sordid miseries of racist colonial violence, or the perverse consequences of a history bent on celebratory, racial and Eurocentric nationalism. We lived decades of paternalistic democracy before decolonisation was achieved. This history should lead Portugal to recognize its colonial and racist heritage, and acknowledge, for example, its leading role in the transatlantic slave trade; its indigeneity and assimilation statutes (until 1961), the colossal colonial war (until 1974), the continued denial of racism, and the offensive presence of a glorified colonialism similar to that which marks most European post-imperial societies.

However, it should be said that in this respect we live in interesting times. Since 2015, we have witnessed an alliance - perhaps inorganic - between sectors of the academy and black Portuguese voices who have sought publicly to record stories, bodies and continued suffering that does not and could not fit in a ‘Museum of the Discoveries’. The societies in which we live at different latitudes are legacies of colonialism and constituted by imperial ruins. Depending on our skin colour, social class, academic background and where we live, we can inherit privilege – by benefitting directly or indirectly from the wealth European exploration accumulated – or we can inherit, even accumulate, the oppression of institutional racism and be exposed to inequality and racist colonial violence.

When I left the colloquium on the decolonization of history and walked into the Diop exhibition, full of black figures appealing to us to attend to the present of colonialism in our lives, I felt like I was fulfilling a prophecy. Unfortunately, on the way back from the exhibition, I remembered that someone at the colloquium had recommended I go – precisely because of the debate about museums and colonialism – and that the happy twist of fate had, after all, nothing to do with chance or divine machination. It is always a pain when beautiful stories are spoilt by memories that prove them wrong.

_________________

Article produced for project MEMOIRS – Children of Empire and European Postmemories, funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 648624).