Hospitality Archaeologies | Interviewing Yannis Hamilakis

This interview arose from a project presented at Culturgest called “Archaeologies of Hospitality” which aims to present the lives of migrants from an archaeological perspective, presenting them as human rather than the pre-conceived ideas of fragile victims that have been transmitted to us by the media.

This project counts with 3 researchers, who are Yannis Hamilakis, Rachael Kiddey and Rui Gomes Coelho. In the first of three interviews we will start our conversation with Dr. Yanns Hamilakis to try and understand more about his previous work and current project.

How did you got involved in this project?

I’m an archeologist by training, I have studied both archeology of pre-historic periods such as the Bronze age or the Neolithic period of the Mediterranean and I have also studied the role of archeology in contemporary society, how monuments and how archaeological sites function in the present; how specific social phenomena including the nation state, rely on archaeology and on archeological artefacts, finds and monuments to construct their own version of reality, their own notion of imagination.

Because of that work on archaeology and the nation and national imagination, I was interested in issues related to sameness and otherness, as well as the border and its effects; in other words, how nation-states define themselves and how they delineate they own borders, vis a vis other people, vis a vis the others whithin the nation.

In that context, migration is an important factor in the contemporary discussion about the nation, because through that act of border crossing people place into doubt the whole foundations of the nation state, the whole idea of how nation should be defined, how it should protect itself and its borders.

So, you can see how that work on nationalism, and national imagination relates to my contemporary work on migration.

Shukran

Shukran

I started this project in 2016, and this was a year after the major exodus of people from Syria who attempted to cross into the European Union via Turkey and Greece and as you know, that was the moment when Europe as a whole became much more aware of contemporary migration as a global social phenomenon.

Of course, undocumented border crossing was happening previously; this is something that has been happening as long as borders have existed. But in recent times, the 2015-2016 moment was when the phenomenon became much more visible in the media and the public discussion in Europe as a whole. I happened to be in Lesbos for something else in 2016, and as you may know, Lesbos is one of the border islands at the center of that border-crossing, from Turkey into Greece and from Greece to the rest of Europe.

I came across the remnants that are left behind in the border crossing, but also the new material realities created by the border regime, for example the camps and the migrant processing centers… The EU calls them reception and identification centers, and certainly identification and processing takes place there, but they are also detention centers. I realized that materiality is central in the border-crossing phenomenon and as archaeologists we are specialists in material culture and its temporality, we are specialists on things, artefacts, and also buildings and architecture. I was thus able to observe how this phenomenon was reshaping the materiality of the island and its landscape.

A combination of these reasons, my own previous interest and work on nationalism and on borders, and the realization that this phenomenon produces new materialities and it requires a very sustained and detailed observation and recording of these new material phenomena led me into starting a more systematic project which involves regular visits and research stays in Lesvos since 2016. I work through a method called “archeological ethnography” which is a combination of archeology as the systematic observation and recording of things that are scattered all over, or even standing buildings, and ethnography as in encountering people in the field and recording their own ideas of this phenomenon.

I talk to people in a more systematic, interview kind of way, but also in a more casual manner, and I observe and record material remnants and materiality as a whole. In some cases this involves team work in a more organized fashion; for example, in 2017 we carried out a survey and a small test excavation of the context known widely as the life jacket ceremony : an accumulation of remnants of border crossing left most of beaches, boats, life vests, personal items and objects.

That specific context was treated by us an archeological site, as something that can be actually surveyed, recorded, photographed, excavated and analyzed as an archaeological assemblage. We do that, but also, very often what I do is more informal observation and recording of how I see materiality working. This is also a project of witnessing, of observing the detention and securitization regime and its effects, and as such it is also a project of activism.

© Yannis Hamilakis, 11 July 2017What are the main topics to retain from the project?

© Yannis Hamilakis, 11 July 2017What are the main topics to retain from the project?

What I try to do is answer some important questions, such as “How does materiality (things, artefacts, objects, buildings) shape the experience of people as they attempt to cross borders”, I try to tackle questions that are not answered by other specialists such as anthropologists, sociologists or political scientists, such “How do border crossers produce themselves new material realities?”

While we very often see the façade of securitization, we see detention centers, we see the camps that are put together by authorities, by the EU, the UN High commission for Refugees, by big NGOs, by nation states or the EU, we rarely see how migrating people themselves reshape the landscape and also produce things as they continue their journey. That agency of migrants themselves, their initiative and their inventiveness, expressed, for example, through the construction of shelters and the production of new artefacts is something very important for me.

In other words, it is an attempt to understand the phenomenon from that point of view of materiality and its changes through time, observe in detail things that are rarely seen or discussed or observed by media or by other specialists who are not really trained into recoding, observing, and analyzing the materiality of experience.

Could you tell us about the object you chose to focus on the project?

Tomorrow I will show several objects so you will have a better idea, but I can speak of some of them now.

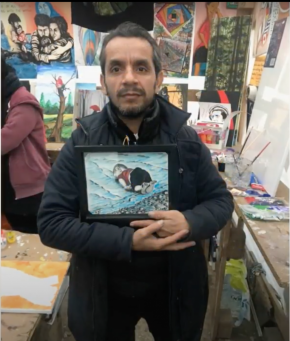

For example, we can talk of the paintings produced by people in camps while waiting for their asylum application process to be adjudicated, works that demonstrate their need both to continue creating while on that liminal state of waiting, but also their own attempt to record their experience through no verbal means.

Shukran Sherzad Also, I work with a group of people from Afghanistan who have actually developed their own self-help initiative and have started a series of schools in camps, the title of this initiative is “Wave of hope for the future”. They have rejected both the official regime of detention by nation-states and the EU but also the initiatives by big NGOs, and they decided to group together the teachers that are border crossers themselves, and develop initiatives, mostly about schooling and training: language classes and training but also art training, mostly painting. In the exhibition which we organized at Brown University called “Transient Matter: Assemblages of Migration in the Mediterranean” we show the work of one of painters, Shukran Sherzad. This is an attempt to continue being active and creative -Shukran was a painter and singer in Afghanistan-, but also train children on how to paint. Many of the paintings are very expressive of the desire to continue the journey, the desire to stay resilient, the need to evoke emotions and feelings.

Shukran Sherzad Also, I work with a group of people from Afghanistan who have actually developed their own self-help initiative and have started a series of schools in camps, the title of this initiative is “Wave of hope for the future”. They have rejected both the official regime of detention by nation-states and the EU but also the initiatives by big NGOs, and they decided to group together the teachers that are border crossers themselves, and develop initiatives, mostly about schooling and training: language classes and training but also art training, mostly painting. In the exhibition which we organized at Brown University called “Transient Matter: Assemblages of Migration in the Mediterranean” we show the work of one of painters, Shukran Sherzad. This is an attempt to continue being active and creative -Shukran was a painter and singer in Afghanistan-, but also train children on how to paint. Many of the paintings are very expressive of the desire to continue the journey, the desire to stay resilient, the need to evoke emotions and feelings.

This is one category of objects I am going to be talking about tomorrow. Another is a little bottle that we found at the “Life jacket cemetery”, a plastic container: it’s not directly linked to migrants, but its directly linked to the experience of border crossing. It contained pills made in Canada, and these are anti-stress pillsl it was found on the beach amongst the life vests and other remants. This actually speaks to the act of solidarity, the volunteers who were on the beach day and night, to help migrants disembark and offer them clothes, information, food, and direct them to the next stop; and that is an extremely difficult and very stressful job and it was extremely stressful back in 2015/2016 with many boats arriving all the time. When we found the little bottle we immediately realized this is a very evocative object that speaks to that attempt to contribute, to help, to express solidarity with border crossing, paying the price at the same time.

Photo courtesy of Yannis HamilakisAnother example is a group of photographs that were produced by young migrants living inside Moria camo (the old Moria before it burned down in late September 2020) which were taken at my own instigation in collaboration with an a small NGO called Refocus Media Labs. I gave them a polaroid camera and asked them to take one photo each, expressing through photography their own idea of what Moria is, what is means to live inside it… So they produced a series of mini polaroids, simple but extremely touching and evocative photos, expressing the sense of crowdedness inside the camp but also the struggle and the desire to produce some kind of normality, some sort of order.

Photo courtesy of Yannis HamilakisAnother example is a group of photographs that were produced by young migrants living inside Moria camo (the old Moria before it burned down in late September 2020) which were taken at my own instigation in collaboration with an a small NGO called Refocus Media Labs. I gave them a polaroid camera and asked them to take one photo each, expressing through photography their own idea of what Moria is, what is means to live inside it… So they produced a series of mini polaroids, simple but extremely touching and evocative photos, expressing the sense of crowdedness inside the camp but also the struggle and the desire to produce some kind of normality, some sort of order.

These are now exhibited in the “Transient Matter” exhibition.

Earlier you mentioned your previous work in Lesvos, could you now tell us the changes you noticed while exploring and documenting border crossings?

When I started in 2016, as I said, it was only a month after the signing of the treaty between the EU and Turkey that actually prevented people from leaving the island, so before, lets say in the big exodus in 2015 and up to the march 2016 people were using the island as a stepping stone; they would arrive on Lesvos but some of them would leave after a few days to go to Athens in mainland Greece, and then continue their journey into countries like Germany.

In 2016 March that stopped because the agreement made in effect the border islands as some kind of open prisons, in the sense that people could not leave the island, they had to stay there, sometimes for years waiting for their asylum case to be discussed and decided. This was the regime in operation up until 2019.

Then, in 2019, there was a government change in Greece and a new conservative government took office and that signaled a big change in how they actually treated the whole phenomenon. They adopted a clear anti-migrant policy many ways, and they started implementing a regime, especially past January 2020, of forced push backs.

© Yannis Hamilakis, 20 July 2019Up to 2020 the number of people that actually where living in Moria, which was the camp for “reception” and processing on Lesvos, reached 20.000 which is a huge number given that the facility was made to hold up 3.000 to 4.000 people. There was a crisis on the island, and you have an anti migrant government as well anti-migrant and local authorities. This generated a series of government supported push backs at sea: the coast guard would prevent people from arriving on the island by pushing them back into Turkish waters. This has been denied by the government but has been reported repeatedly by many investigators working on the island, it has been discussed in the EU parliament and covered by some journalists, it is a well- documented case. The number of arrivals has gone considerably down because of that attempt to push people back and of course since the pandemic the numbers have also decreased.

© Yannis Hamilakis, 20 July 2019Up to 2020 the number of people that actually where living in Moria, which was the camp for “reception” and processing on Lesvos, reached 20.000 which is a huge number given that the facility was made to hold up 3.000 to 4.000 people. There was a crisis on the island, and you have an anti migrant government as well anti-migrant and local authorities. This generated a series of government supported push backs at sea: the coast guard would prevent people from arriving on the island by pushing them back into Turkish waters. This has been denied by the government but has been reported repeatedly by many investigators working on the island, it has been discussed in the EU parliament and covered by some journalists, it is a well- documented case. The number of arrivals has gone considerably down because of that attempt to push people back and of course since the pandemic the numbers have also decreased.

The main changes I saw was the industrialization of the push back strategy and of course, the fire at Moria in September changed everything. The EU has just issued a new policy pact on asylum which is still under discussion, but it promises more and faster deportations and tries to intensify what we call externalization of the border, which is to convince other countries outside the EU to stop people before actually crossing into EU. Turkey has already been doing that for some years, and countries in Africa are also doing that, but this is going to continue more intensively if this plan is implemented by the EU.

How do you think that policy affects the EU?

The EU unfortunately does not see this as an issue of solidarity with the people who are trying to cross, because most of them, the vast majority of them are actually fleeing persecution, or poverty, or war or various attempts of criminalization at their own countries. They see it primarily as a matter of internal solidarity amongst the nation-states. This new pact provides for support to countries that are entry countries like Greece, or Italy, or Spain and it promises a fair sharing of the burden. But this new pact does not signify a change in the policy towards migration, the policy of “Fortress Europe” is still the policy that EU is going to follow.

So I am not really hopeful that this new policy is going to change things for the better, but the good thing is that many “bottom-up” initiatives, many movements and many people who are still working at the border actively express their solidarity with border crossers. And of course, with local people as well, and they strive to debate migration not as a threat, but as a a global phenomenon that’s going to intensify in the future.

I edited a volume recently called “The New Nomadic Age”, and the title was deliberate chosen to signal that we have entered a new age in which border crossing and global movement will become more and more prominent and intense.

War, poverty, and persecution are now the main causes but climate change is going to be increasingly the next major factor which is going to displace millions of people. We are facing a new reality and I think that new reality is not seen as such and understood by the EU and other countries in the Global North.

Is this “new reality” you mentioned, capitalism’s fault?

Yes, global inequality, social inequality to do with capitalism, but I think it goes even further… It has to do with the colonial history of Europe as a whole: I see this phenomenon of migration from the global south to the global north as the latest phase in the long history of racialized capitalism and colonialism.

Many of these people who are trying to cross are coming from previously colonized countries by Europe. We know that, that long history of colonization has an impact in the present in terms of structural inequality, poverty, dispossession and war, and at the same time that we are seeing is the inability of Europe to come to terms with its own history. Which is a history of colonization, of course, instigated by proto-capitalism and capitalist developments as well as the hierarchy of racialization and the legacy of whiteness and white supremacy which fueled the whole colonial condition.

Photo courtesy of Yannis HamilakisWhat do you expect people to take from your current project?

Photo courtesy of Yannis HamilakisWhat do you expect people to take from your current project?

First of all, I want to convey some of the material realities on the ground because I think it is important to talk about these things beyond what we read in the news, and I am hoping that there will be some discussion about the shapes and causes of phenomenon as well as the prospects, in view of establishing also some alliances and connections with people working as scholars and activists in border-crossing contexts. And I hope that people understand that this phenomenon affects our lives no matter where we live, in Greece or in Portugal or in other parts of the world. Seeing all these phenomena, both border crossing, but also the securitization, detention, and deportation apparatus, and the push backs which all signify a permanent state of exception at the border, seeing them as central and crucial phenomena that should concern us all, is something very important that I want to get across.

Has there been any particular story or person that left its mark on you?

I have many, many, many stories that have made a huge impact on me, I am going to be giving some kind of examples tomorrow.

I am going to go back to that story I mentioned earlier about people from Afghanistan deciding inside the camp of Moria to start their own initiative, because I think that specific attempt to self-organize, to bring teachers together who happened to be from border crossers themselves and encourage and convince them to do something collectively, against both the authorities of the camp and the regime of big NGOs, is extremely important for me, it speaks to their resilience, their initiative, their agency, and their profound understanding of the reality they experience, because what they were trying to do is to say “look we reject both what you’re trying to do with us, as in containing us through the regime of security, but also we reject the patronizing mentality of the big NGOs; we are not victims. We are people on the move who are facing certain difficult conditions, but we have the skills and we have the energy, and we have the ability to organize ourselves”, that is for me very important, because it actually critiques different facets of the whole assemblage of migration: the authorities of the camp and their regime of securitization as well as the regime of what people call the humanitarian reasoning, the idea that these people need to be helped because they are helpless victims. Instead, and they say to them and to us, to all of us, “No, we are not, and if you want to help ally with me, be in solidarity with me, walk with me”.

© Yannis Hamilakis, 10 April 2016

© Yannis Hamilakis, 10 April 2016