Lee-Ann Olwage: “If we are looking to globally improve the lives of people living with dementia, then we cannot overlook the part that concerns different cultural perceptions”

Lee-Ann Olwage is 37 years old, was born in South Africa and considers herself a visual storyteller. Throughout her professional career as a photographer, she has captured images that reflect the way in which different cultures and different communities interpret mental health. She has also explored other issues that she fights for daily, such as those relating to the LGBTQIA+ community.

Recently, in a photographic project, she documented the lives of elderly women affected by dementia in Africa. Entitled “The Big Forget”, the project – which is still under development – had a photograph distinguished by the World Press Photo 2023 contest. The award-winning image was taken by Olwage in 2022, during one of her visits to Ghana, more specifically to the “witch camps” that have existed in the Gambaga region for more than 100 years.

Lee-Ann Olwage, who admits she struggles with her own mental health issues, also has family members who have suffered or are suffering from Alzheimer’s. For this reason, she states that, with her work, she aims to create a space in which the people she photographs can play an active role in creating the images and that, above all, makes them feel like the true “heroines” of their own stories.

Sugri Zenabu in The Big Forget. Winner photography of World Press Photo.

Sugri Zenabu in The Big Forget. Winner photography of World Press Photo.

You were born in South Africa. What are your main childhood memories?

Oh! I like your approach, because I believe that everything that makes us, us, makes us the storytellers that we are.

I’m very proud of South Africa. I love my country. I think we are one of the most amazing countries in the world and I love that we are so diverse. There is a wonderful mix of people here. A great mix of cultures. We are colourful country, we are friendly and that is something that sets us apart. If you ever visit, you will see that there is a lot of magic here. For the most part, this is how I feel about my interactions, but also about the way I tell stories, not just about South Africa, but also about the African continent itself. I think that, for a long time, stories were told about Africa and South Africa that, in reality, did not show how beautiful we are as a nation.

About my childhood… I was born in Durban but I grew up in the Eastern Cape. I also lived for a while in Lesotho - which is a landlocked country in the centre of South Africa. I was very lucky to have parents who always encouraged me to explore and who always supported my imagination and self-discovery. Additionally, I think a lot of my grandfather as the first storyteller I was introduced to. I think that’s where my love for storytelling comes from. As for my journey as a photographer… well, I always knew I wanted to be a storyteller, but I think that ended up being almost an “accident” on my path - although I believe that we should never deviate from our route. After finishing school, I studied Film Directing and Scriptwriting. After that, I worked on films as a set decorator for about nine years. And I think that really influenced the way I explore visuals or narratives today. I realized that I didn’t just want to document what I saw, but also show the textures and how I could incorporate them into the stories.

Lee-Ann Olwage

Lee-Ann Olwage

When I was about 28, I went on holiday to Indonesia with my previous partner and he bought a camera. Although, at the time, I thought it would be a waste of money, the truth is that, while we were there, I ended up falling in love with photography. I fell in love with this way of telling stories, but it took me some time before I considered myself a photographer. When I turned 30, I decided to make career change, but I could not study photography. I was going through a time in my life where I had a lot of financial burdens. For that reason, I decided to join other photographers to help them with their work and to learn more about photography. This way, I was also able to earn some money, while telling stories that interested me. That period also helped me a lot to think about visual storytelling differently, because I was always surrounded by commercial photographers, that is, people who photographed products or worked with models. These professionals usually use a lot of lighting that comes from a studio, and I always knew that wasn’t what I wanted to do. On the other hand, I realized that, later, I could apply what I was learning from them in my own work. For example, I watched how carefully they photographed, whether it was a piece of cheese or a person! They thought, in detail, about how they wanted to present that image and what they intended to convey with it. This made me question how I could take documentary stories that, as a rule, already have a certain aesthetic, and deviate from that a little, giving them another visual quality. In other words, how I could combine documentary work with commercial work, but also bring a little of the cinematographic side to my images. And I love that! I love being able to put these stories in a different way and simply give them a visual quality that sets them apart, rather than just photographing what I see when I walk into a scene.

If you had to point out a moment that defined the beginning of your professional career as a photographer, what would it be?

I love working on films, but I always felt like there was something more I needed to do. When a very close friend of mine passed away, I decided to buy an old film camera. I had no idea how to use it [laughs]. I had heard about a group called “The Black Mambas”. It’s an all-female unit of rangers who protect wildlife from poaching [in South Africa]. They are, quite simply, the most phenomenal group of women. As I felt like I needed to redirect my life in some way, I thought that maybe if I spent some time with them, I would have some clarity about the path I wanted to take. Having said that, I got in my car and drove to the opposite side of the country, where I spent two weeks with them in the forest. It really was an amazing experience and I documented everything. Then someone saw this work, I said it could be published and that’s how things started for me.

The Black Mambas

The Black Mambas

But you don’t consider yourself a photojournalist, right?

That’s a great question and the answer is constantly evolving! I definitely consider myself more of a visual storyteller. I think it took me a long time to consider myself a photographer because I didn’t feel confident. It took me a long time to discover that I held that title. But no, I don’t consider myself a traditional photojournalist. I think there is a place where documentary work meets storytelling. I find myself somewhere in the middle.

And what was the first big project you published?

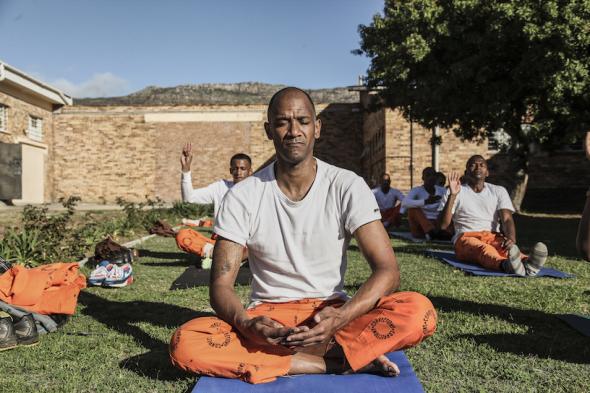

The first project I published was about yoga in Pollsmoor Prison, one of the most notorious prisons in the world (located in Cape Town, South Africa). So, I heard about an organization teaching yoga to prisoners and I thought that was absolutely extraordinary. In my opinion, yoga is an excellent way to calm the mind, it’s something you can do in a tiny space, and it can really change your life. It took me a long time to get permission to enter Pollsmoor. For six months, I drove there and stood outside, hoping to make contact. When I finally got permission to enter, I met the right person, and they gave me permission to photograph.

Do you consider yourself a persistent person?

Yes, I think I’m very driven. Many people would not be willing to invest so much of their time until they were authorized to enter these places. I, on the other hand, love it. I love the way people get to know you and see you return time and time again. I think it’s important to show people that you’re taking your work seriously, because it’s a great privilege to be invited into someone’s world. You can’t just demand that. It doesn’t work like that.

Yoga in Pollsmor

Yoga in Pollsmor

Did your personal experiences have anything to do with your decision to explore themes related to gender and identity?

Absolutely! As a female photographer, I have always liked to direct my work towards gender and identity issues. I work with the gender fluid community, with Drag Queens, with women and girls. For me, it is very important to tell the stories of these people in Africa, because they really become the heroes of their own lives. Often, [these women] are shown as victims. However, if you look at the work I’ve done on child marriage or female genital mutilation, you’ll notice that I made the decision - very consciously - not to photograph young women who had gone through those experiences, but rather to photograph women who were already empowered and highlight that reality. For me, this is the most important thing. There are already too many images in which these people are seen as victims of these circumstances. We need them to be presented to the world as heroes of their own stories, because they are. And that side isn’t always visible, because sometimes it’s easier to show something that’s horrible.

Why do you think that happens?

I don’t know if it has to do with the way the media aligns and looks for, or if people simply don’t spend enough time in the communities. Often, when I start a project, it seems like that is the story, that is, it seems like what I’m seeing is something obvious. However, if I’m starting a project for the first time, how can I know that it’s the real story? First, I need to dedicate time, I need to ask questions, I need to feel… and only then, little by little, will I be able to show what my ideas are. It’s not your story, that is, you don’t know anything about the people you’re meeting and photographing. You have to really listen and be available. That’s where the story will reveal itself. I think that in many situations, people continue to only look at what is on the surface.

Lee-Ann Olwage

Lee-Ann Olwage

Mental health is also one of the central themes in your projects. Why do you feel the need to talk about it?

I’ve always struggled with my own mental health issues, which is to say, it’s something that’s quite familiar to me. It is a topic that also has many stigmas associated with it. For that reason, I think it’s important to talk about the subject, visualize it and share people’s various experiences.

On the other hand, I also find it quite interesting how different cultures and different communities around the world perceive mental health. On the one hand, there are countries where the disease is more accepted, but where some prejudices are still felt within the workplace, for example. On the other hand, there are countries in which spiritual beliefs persist and where it is believed that witchcraft may be, in some way, related to this type of problem.

Mental health is a universal topic, so [in whatever context] we can say that many people end up feeling isolated [from their own community]. I think that everyone who has already encountered mental health problems, even if for brief moments, can identify with this.

As you mentioned a moment ago, you also explore and capture images that relate to the LGBTQIA+ community. What drives you to expose the reality of black people who are part of this community?

South African law is one of the most progressive in Africa when it comes to the rights of the Queer community. In other words, it is supposedly more acceptable for these people to get married or for gay couples to adopt babies [in South Africa]. When you realize that this reality is possible on the African continent, it seems like you discover a wonderful refuge there. However, through the conversations I was having, I realized that the experiences of this community and their daily lives were very far from that. I then wanted to understand where and how these people got married, where they felt not only safe, but also celebrated, where they could be themselves and feel embraced by the community around them.

At that time, I was introduced to the Drag Queen beauty pageants that take place in South Africa. For about two years, I documented these performances, and it was simply wonderful. It was incredible to see people shine and be truly celebrated for who they are. On the other hand, it broke my heart when I saw them remove all their makeup before going home, because they could get killed on the way.

#BLACKDRAGMAGIC

#BLACKDRAGMAGIC

By being with this community, I began to understand how it wanted to be represented or exposed. My initial idea for the #BLACKDRAGMAGIC project was to play with gender and, therefore, I started by photographing Drag Queens using very strong light, in order to accentuate their facial features and replicate the contrast that existed between the masculine and the feminine. Right after the first sessions, one of them saw my work and told me, in all honesty, that she didn’t like her image in the photographs. Her words were: «I don’t really like this picture because your lighting is not making me look beautiful. It’s making me look hard». And that’s when I realized I was doing everything wrong! They wanted to feel beautiful, and I wasn’t able to expose them in that way. I decided to completely change the way I was working with lighting, and it was great to receive that feedback from them. It is important to know how to listen, understand and learn. Her feedback made me adapt my work to each person and made me more attentive.

This is what I’m talking about. You can have good ideas when you start planning a project. But if you realize that they don’t meet the reality of that community, then it’s best to chuck them out the window. If you are not part of it, you will always be the person who knows the least about the story you intend to tell. Because it’s not your story. I think we should always have an initial plan as a basis, but then we should listen, learn, adapt and change everything we have to change, until the person comes to you and says: “this is it. This is me”.

The first photographs you took for “The Big Forget” collection were taken in Namibia. What led you to create this project for which you were distinguished at World Press Photo?

Well, my current partner had read an article that covered the story of a woman called Ndjinaa Ngombe, who belonged to a Himba tribe in Namibia. People in her community had chained her for 20 years, because they were afraid of her. However, there was someone from an Alzheimer’s Organization who found her, detected the symptoms [of dementia] and explained to the community what really was happening to Ndjinaa. Eventually, she ended up being transferred to a home and that’s when we decided to go look for her. Luckily, the period of confinement resulting from COVID-19 was just ending when we decided to travel to Namibia. We still had to wait a few days, but we managed to be the first South Africans to cross the border. We met with Ndjinaa and her brother, but also with some members of her community to understand their side. In other words, we wanted to understand how they had interpreted Ndjinaa’s symptoms at the time, what behaviours she had that were seen as something scary and, of course, why they decided to chain her up for 20 years.

I was about to start the project, when I thought: “well, I don’t want to photograph people who are chained”. Ndjinaa was no longer in prison, but there were many others that I could photograph if I wanted. But that’s not what I intended to show. I also think we’ve seen enough of this. I wanted – and still want – to present this reality in a different way. And that’s how it all began. I was taking some photographs, spending some time within the community. A year later, I had the opportunity to return to Namibia with National Geographic and that was when I started to flesh out the body of the work.

The Big Forget, Ndjinaa Ngombe

The Big Forget, Ndjinaa Ngombe

As a photographer, how do you explore or highlight something so abstract and/or invisible, such as mental health issues, in images or portraits?

I’ve been working on “The Big Forget” for three years and it’s only now that I feel like I’m managing to find a visual language for the project. But that’s the big question: how do I show something that isn’t visible?

When I returned from my first trip to Ghana, I remember getting home and feeling like I had completely failed. The photographs weren’t what I wanted… When I went to Ghana for the second time, I still couldn’t capture the images the way I had imagined for a few days. At the end of the last day of this second trip, I had already gotten into the car to leave, when I asked the driver to stop. I still had the feeling that something was missing. I went back to the women and asked them to walk. My idea was to capture moments that reflected the true mental image of the spiritual beliefs of that region. It was only that time that I really felt like I was able to take a photo that showed that. Still, I believe there is a lot of work to be done.

For this project, you also wanted to portray the reality of the “witch camps” that exist in Ghana. How did you discover them?

My work is always done in the long term, that is, I think of it as a book with several chapters. I don’t want to focus on just one topic. Having said that, I started a lot of research, got in touch with different Alzheimer’s organizations and talked to a lot of people in Uganda and Kenya. Later, I received a grant from the Bob and Diane Fund – they support visual storytelling about Alzheimer’s and dementia - and, as I had heard about witch camps in Ghana, I decided to visit them. I realized that I could potentially add another chapter to my project.

As I told you a little while ago, the first trip was very difficult. In addition to not being able to get the photographs I wanted, access to the camp itself was complicated. The man who was in charge of the camp and did all the translations followed me everywhere. He never let me observe women without being there. I felt like I was seeing things through his eyes, from his perspective. And the place itself was already distressing. These women live in very bad circumstances. At the end of the day, I returned home and started thinking about how I would tell this part of the story.

Later, I was lucky enough to get another partnership, this time with a German newspaper - Der Spiegel. When I returned to Ghana for the second time, I took some of the photographs I had taken and showed them to the women. It was quite interesting, because they couldn’t remember me, but they could recognize themselves in the images!

During this second trip, I also discovered that one of the women, who had previously been in the camp, had returned home and been reintegrated into her community. It was wonderful to know that. From a medical point of view, there was great concern about educating everyone about what was happening to her. Furthermore, the community also worked with a local religious leader and I considered that a great sign of respect – if it’s a Christian family, they’ll take a pastor, if it’s a Muslim family, they take a imam – and it was incredible. I lived wonderful moments with this woman. I remember she was wearing a Beatles t-shirt and, when I asked to photograph her, she went to change and put on a beautiful dress. In other words, she was aware of the way she wanted to appear in her photograph. There it is, people know how they want to be presented to the world. It was really a profound moment for me. And it was even more wonderful to see her back home.

It was on that same trip to Ghana that I took the photo of Sugri Zenabu (awarded photograph in the World Press Photo contest 2023). In the end, I felt like I was more connected to the project. It’s all a matter of time and knowing how to invest it.

And what was the reaction of these women when they welcomed you?

Konduug Laar, the woman who change the clotheOf course, when there is a language barrier, it is much more difficult for us to communicate and connect with people. There were times when I would just spend hours with them while they cooked, for example. But those women were definitely very available. It was amazing. I felt really free in that environment. And I think being a woman was one of my advantages. I think that, by being a female storyteller, I was able to access certain spaces that, perhaps, a man would not be able to access, even if he was doing exactly the same project.

Konduug Laar, the woman who change the clotheOf course, when there is a language barrier, it is much more difficult for us to communicate and connect with people. There were times when I would just spend hours with them while they cooked, for example. But those women were definitely very available. It was amazing. I felt really free in that environment. And I think being a woman was one of my advantages. I think that, by being a female storyteller, I was able to access certain spaces that, perhaps, a man would not be able to access, even if he was doing exactly the same project.

You explained, in some interviews, that these “witch camps” are, in fact, quite controversial, because, despite all the difficulties these women face, they are also safer than if they were in their community. How did you expose that contrast in your photographs?

There really is a strange contrast between being protected from threats from your own community and living completely isolated. That was what caught my attention the most: how can these women be so far from home and the people they love? I think that, during old age, we should be close to our family.

It was very sad to realize that these women had already been living on their own for 20 years or more. The feeling of isolation was very present, and I relate this feeling a lot to the topic of mental health. Whatever the situation, anywhere in the world, people living with a mental health problem feel isolated. Of course, if you look at the circumstances of those camps, you realize that people live in terrible conditions, without enough food… it’s really complicated. How do you find a balance between safety and these types of conditions? The “Go Home” project – which reintegrates some of these women into their community – ends up being a help, but it is always a very time-consuming and expensive process. They focus on one person at a time, and there are at least a hundred women living in the camps. Many of them will simply never return home.

Why the title “The Big Forget”?

Great question. When I started the project, I discovered that in most indigenous African languages, there is no word for “dementia”. In Namibia, some people refer to it as “confusion”. In French-speaking countries, the word “madness” is often used to describe the disease. In other words, the terms that are used already have a very negative connotation. So, I decided to contact Muriel, a colleague from Madagascar who I’ve been working with this year, and who belongs to an amazing Alzheimer’s organization. During that phone call, I asked her how she would describe dementia, to which she replied: «it’s like this big forget, like this big loss». I thought: “that’s it! That is the best way to describe it”. So that became the name of the project.

As you mentioned, this is a work that you intend to divide into several chapters. What distinguishes the first one you did in Namibia from the one you did now in Ghana?

I think that in Namibia I was lucky to meet very different families. It was my first introduction to the project. I watched, up close, the way people were being treated. I met Ndjinaa Ngombe, for example, who lived in a foster home – something that is very rare in Africa. I met people who were in the care of a family member, because no one else wanted to get involved in their treatment due to the stigma. But most of all, it was incredible to realize that, as soon as there is more information about what is happening to people, and if we help family members to better understand dementia, they really learn to care for each other. It is a wonderful example of how an entire community can become part of a particular model of care.

On the other hand, we have to accept that in many communities, superstition and spiritual beliefs are the basis of all areas of their lives. Not just in Africa, but all over the world. It’s the way they interpret things. And when it comes to mental health – something that manifests symptoms that are difficult to explain – there will always be someone who will act in a scary way. So, people in these communities will be guided by their spiritual beliefs, their belief in witchcraft or supernatural phenomena to explain these behaviours. And that makes perfect sense. In fact, the way these communities perceive health in general is very complex, it is not just about mental health. From the moment you work with local nurses, for example, you begin to understand their culture much better. In my opinion, it is possible to balance cultural beliefs with medical knowledge and information.

The Big Forget

The Big Forget

In your opinion, since there is no concrete term to describe dementia in these countries, what is the best way to approach the topic there?

From what I’ve seen, I think the best solution is to work with local health professionals. The point is: if we try to introduce an NGO [Non-Governmental Organization] or any other institution to a certain culture without knowing it, we will never know how to approach the problem. Therefore, if we want to help these communities and be successful, we must invest more in training local nurses and doctors. There are already some healthcare professionals who are doing this, but it is something that deserves to be supported on a much larger scale.

And how can we respect their ancestral traditions, but, at the same time, improve their quality of life and increase their literacy about mental health? How do you find the balance you were talking about a moment ago?

One of the most interesting things I learned was that people visit traditional healers, but they also go to the doctor. In other words, there is this intersection of spiritual knowledge with medical knowledge. These are things that coexist. And I think it’s important to understand that it’s not about trying to separate them, but about analysing how they can work together. That is, whether it is doctors from a local hospital, traditional healers, physiotherapists, local nurses… if there is harmony between them all and if they all support education and the various components of medical services, I think the information will be well received by the communities. However, even though local health professionals are already doing their job, they still need a lot of support from the Government and the World Health Organization (WHO). If we are looking to globally improve the lives of people living with dementia, then we cannot overlook the part that concerns different cultural perceptions.

So far, with this project - “The Big Forget” - what would you say you have learned about the impact of dementia in the sociocultural context of sub-Saharan countries?

There are differences when it comes to gender, definitely. For example, women are accused of witchcraft more often than men. I also noticed that, when someone is needed to take care of a family member, they always ask young girls for help. In fact, they even take them out of school so they can take care of their families. In other words, there ends up having a long-term impact on the lives of these girls.

I learned that it doesn’t matter where in the world you are. You may be excluded from your community, either because you have been placed in a care home in the United States, or because your behaviour is scaring people [in Africa]. There is definitely a great deal of prejudice surrounding mental health. And for me, it was really important to highlight how other people are experiencing it.

The Big Forget

The Big Forget

There are people who suffer from dementia in your family. Was this reality also something that motivated you to create this project?

Absolutely. My grandmother had Alzheimer’s and my father was diagnosed this year. What always fascinated me was realizing how different cultures and different communities interpreted the same issue. In other words, this was always my main objective when creating this work. But then I started thinking about how lucky we were with my father, for example. We were able to take him for a brain scan (CAT scan) and receive a quick diagnosis. While carrying out this project, I realized that many of the people I met in rural communities will never be able to see a neurologist. They will never be able to get a formal diagnosis. And this is due to the lack of specialized health professionals within these communities. If there isn’t even a doctor to make a diagnosis, how will they ever be able to treat the problem or even understand it?

What’s next for “The Big Forget” project? What will be its next chapter?

In the next chapters I would like to focus on the spiritual beliefs that exist in Benin (a country in West Africa) regarding mental health. I’m also thinking about writing a chapter dedicated to an incredible nurse I met in Namibia. He printed and laminated an infographic prepared by the International Alzheimer’s Organization – which contains the 10 warning signs of dementia – and now takes it with him to every rural community he visits, so he can examine people who would probably never be able to see a doctor. This way, he can give the family a possible diagnosis, but also educate them and give them more information about the disease.

In addition, I am also doing a long-term work dedicated to girls’ education. To this end, I have been going to countries like Kenya and South Africa, and I hope to be able to go to Nigeria and Malawi.

As a photographer, but also as a person, what do you highlight in your personality that might be important for you to be able to work with these most vulnerable communities?

I think kindness is one of the most important things for me. And it doesn’t take much to be kind. Before you are a journalist, you are human, that is, you have a certain level of sensitivity. The same happens with photography. There were so many pictures I didn’t take, because it didn’t feel right. We have to know when to step back and put the camera down. I think this is very important. The way people feel around us shows in the images.

We often say that photography is such a dishonest medium, because you can make a photograph look like anything. But we can never lie about how the person being photographed feels about the photographer. For me, this is always so blatantly obvious in the gaze. It is something you can quickly understand. In my opinion, the most important quality we should have is being able to work with kindness, with respect, and remembering that we are human before anything else.