Festa do Avante, although hidden, conflicts exist over all three days

This weekend is the 41st Festa do Avante. The festival is organised by the official newspaper of the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP) and declares itself “the greatest cultural event in the country.” This claim positions the Festa as non-partisan, popular tradition, which to a degree explains its relative longevity and success: thousands attend every year. The Festa’s well-known dimension of militant communist mobilization, and the posture of international solidarity assumed by its management as well as by the artists involved renders it, however, a professional and international affair. When the Festa began four decades ago, these attributes were very uncommon in the world of artistic programming. Its wide-ranging music and artistic programme, incorporating non-European musical genres and repertoires (today often mistakenly named ‘world music’), has appealed to very diverse audiences. The Festa’s programme owes a great deal to Ruben de Carvalho. Carvalho is a member of the PCP Central Committee, but also one of the pioneer cultural programmers in Portugal.

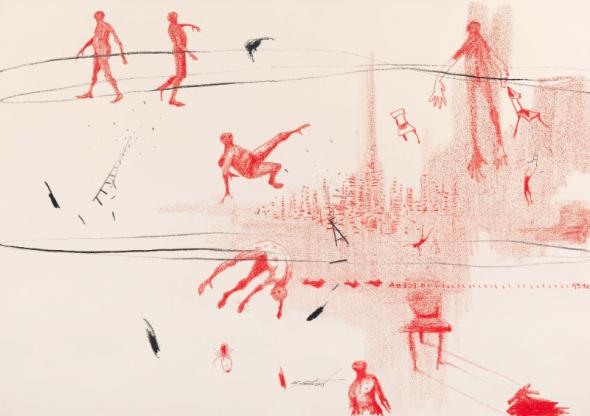

in city | 2017 | Nú Barreto

in city | 2017 | Nú Barreto

The Festa do Avante is, however, a political instrument which retains the markings of the European communist movement. Like other festivals organised by other Communist Parties, it remains an important stage for the visibility of European communists. We can compare the Festa do Avante with the Fête de L’Humanité in France, created in 1930 in the context of the Popular Front. In the intervening decades the Fête has undergone several changes in format as the French Communist Party (PCF) itself as changed. In 1999 the Fête ceased to be run by the PCF at all and became a festival of world causes with a very eclectic line-up organized by a range of left-leaning associations and parties. Another example is the Festa de l’Unità, organised by the Italian Communist Party from 1945. This event, too, has undergone many changes in content and organization – even its name has changed – but it has retained for almost a century the peculiarity of being a festival held in many different Italian cities.

Although these different festivals have evolved in very different ways, they have enough in common for us to think of them together as European communist festivals. By genealogy they are associated with ancestral festive calendars and with religious or pagan agricultural festivals. It is no coincidence that these events happen (with winter spin-offs) in late summer - regeneration time - and although there are always one or several programmers involved, programming is taken on as collective work, like traditional festivals with no single declared instigator.

The Enlightenment debate between Diderot and Rousseau on the role of nature and culture in forming the citizen seems far away, but here we seem to find a synthesis. The festivities of the European Communist Parties are militant and pedagogical cultural activities typically carried out, if not in the midst of nature and in parks, at least in the open air. This fits with Rousseau’s precept when he states: “It is in the fresh air, it is underneath the sky that you must gather and give yourselves up to the sweet sentiment of your happiness […] plant a stake, crowned in flowers, in the middle of a square, gather the public there and you will have a party. Even better: turn the spectators into spectacle; make the public actors themselves; let each person see themselves and love themselves in the others so that all be better united.” (1)

In the case of the Festa do Avante, this idea of the idyllic meeting between man and nature at the time of the feast is palpable in an article published in the newspaper Avante in 2012 by the militant historian Miguel Urbano Rodrigues. He describes the festival that began in 1990 to be held on a farm south of the Tagus: “the Quinta da Atalaia, a former agricultural farm, on the south Bank of the Tagus estuary, a green and quiet corner of serene beauty.”

Nevertheless, for all that these organizations claim the status of popular festivals they have important distinctions from the festivals of non-explicitly partisan organizations. Despite their range of cultural and eclectic programming, only the Communist Party festivals claim the fight against ‘cultural hegemony’ as their objective. This concept is key to António Gramsci’s theory of power, and names a process by which states destroyed traditional and popular cultural practices and controlled the media. One form of resistance to this hegemony is in the intervention of intellectuals and in a process of cultural education in which the Party can play a leading role. This is one way of understanding the festivals’ vast programs of debates, international exhibitions, fairs and book launches. According to the organisers themselves, these events address both political causes from every era and works that deconstruct cultural hegemony itself.

This distinction is particularly pertinent in the case of the Festa do Avante given a certain continuity of political management in its history. José Neves studies this in a recent article (2), summarising theFesta as “an anticipation of a post-conflict age, an age of the end of the war between peoples and the end of the struggle between classes. It is, in fact, an archetype of a post-revolutionary society often celebrated by communists and even their opponents.” (3) Neves argues that the Festa has been able to construct itself as a utopian time-space for two principal reasons, among others. Firstly, because the work of putting the event together depends on free militant work and therefore stands apart from processes of capitalist exploitation. Secondly, because of the variety of activities the Festa incorporates - from concerts to gymnastics and gastronomy. “Its programme fits all of this together smoothly, with no dissent emerging from gender conflict or minority voices. Perhaps this is because the Festa has become an annual pacifist celebration and has a global participation under the slogan of revolutionary internationalism.”

Creating this illusion of a post-utopian world that conceals war has a price: the absence in those three days and in that space of any type of explicit conflict, even contradiction: there is no place for the conflict of generations, gender, music, of tents of national and international producers, and so on. Only in the closing address by the secretary-general does real life return to combat, contradiction and even war. The logic underpinning this temporal utopianism reveals itself in the way the trauma is concealed and memory, or many memories, are excluded from the programme. Having consulted various of theFesta’s programmes, it is surprising that notwithstanding the proliferation of activities, two themes are practically absent. These are colonialism and post-colonialism. Yes, there are declarations of solidarity with the stabilized narratives of the struggles for independence carried out by movements or parties of Marxist inspiration, just as there are tributes to heroes of these movements. Many artists and writers from those new African countries participate. But the analysis of colonialism itself is absent to such an extent that in the twelfth Festa, in 1988, “Communists celebrated 600 years of the Portuguese throughout the world” without any criticism at all of this process of expansion. An exhibition on the ‘Discoveries’ was put on, preceded by another on the Cosmos, attended both by the Soviet astronaut Vladimir Solaviev and by pieces of Sputnik. There are no debates or activities focussed on the genesis of the independence movements or on negritude or pan-Africanism. The PCF’s Fête de l’Humanitésuffers from the same problem, not least because of the PCF’s ambiguous relationship with Algerian independence. In the same way, the questions of trauma from the Colonial Wars, decolonization andretornados were always absent from the contribution of Communist Parties to the construction of new narratives about colonization and its genesis in imperial European history.

Similarly absent are debates and references to the problematic of postcolonialism and to its various authors of broadly Marxist inspiration, with the exception of a slight nod to Amílcar Cabral. He, however, is presented more as the hero of the struggle than as a crucial theorist of pan-Africanism and what would become postcolonialism. As part of a contemporary approach to deconstructing cultural hegemony, it would be good to see intellectuals intervening in the question of (revisiting) colonial memories in the present context. Furthermore, it is not possible for intellectual work seeking to produce new knowledge to occlude the Soviet state’s own responsibility for the colonization of all the now-republics of the former USSR and its satellites.

Indeed, amnesia about this historical fact may be devastating, in the short term, to these former colonies (some of which have already been reoccupied) as Katerina Brezinova clearly foresees. “Post- communist Europe, whose national imaginaries are still strongly marked by the heritage of German Romanticism, is witnessing new, emerging forms of Modernity that may or may not resemble the experience of Western Europe. In some countries of the region important local counter-currents are forming against the new realities of this difference. We will be in a better position to understand some of these current conflicting trends by taking seriously the violent reaction against migration and multiculturalism and the resurgence of ethnic and religious intolerance …” (4) To continue the Festa in its current vein might seem like a post-revolutionary utopia but it is neither a credible nor relevant to all the peoples of the world.

_________________

(1) J.J. Rousseau, «Discours», Œuvres Complètes, Paris : Armand Aubré,1832, p.235.

(2) José Neves, «A militância comunista enquanto prática utópica– da resistência antifascista à sociedade pós-disciplinar », Ler História [Online], 69 | 2016, colocado online no dia 11 Março 2017, consultado no dia 22 Março 2018.

(3) Ibidem.

(4) Katerina Brezinova, “Polémica em torno da diversidade? A República Checa pós-comunista face às novas realidades da diferença”. in, António Pinto Ribeiro (Org.), Podemos viver sem o outro? As possibilidades e os limites da interculturalidade, Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 2009, pp.123-4.

_________________

Article produced for project MEMOIRS – Children of Empire and European Postmemories, funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 648624).