Restituting artworks: a decisive step in the process of decolonization

Piroga, Ubundu, RDC (1958), at AfricaMuseum hall | 2018 | photo by MEMOIRS

Piroga, Ubundu, RDC (1958), at AfricaMuseum hall | 2018 | photo by MEMOIRS

On 7 December 2018, the Belgian Royal Museum of Central Africa was finally closed and the AfricaMuseum opened in its place. This new Belgian federal museum replaces the Museum of the Congo, which King Leopold II created in 1898 following the Brussels International Exhibition in 1897. That exhibition aimed to legitimise and glorify Leopold II as King of Belgium and as the absolute owner of the territory and resources of the Independent State of the Congo. But the exhibition also aimed to promote the scientific study of that territory and to exalt colonial action itself. Such an imposing infrastructure was created for this temporary exhibition that it became permanent. The ensuing volume of visitors and collections, however, quickly rendered even that space cramped. Work began on the present majestic building, funded by the proceeds of exploiting the Independent State of the Congo. King Albert I officially inaugurated the new building in 1910, four months after the death of Leopold II. Until 7 December this year, that building housed the Royal Museum of Central Africa in Tervuren. Initially this continually growing collection included works from the Congo, Burundi and Rwanda. Many of the works were objects of worship, handicrafts, minerals, different animal and vegetable species and even large embalmed animals. The collection included most of the works exhibited at the 1897 Brussels International, with the exception of the 267 Congolese people also put on show in villages that had been built in the open air. Since the millennium, such live displays of people have been referred to as human zoos. Belgium maintained this set until the 1958 Brussels World Fair, the first world exhibition after WW2 and the last to include human zoos. In 1897 seven of the Congolese died due to poor living conditions outside in the gardens. Initially they were buried in an unmarked mass grave, though they now have their own grave in the grounds of a Tervuren church. That site is now a place of memory for the Congolese diaspora. The Flemish director Chokri Ben Chikha staged the play Commission de Vérité (Truth Commission) there, the story of a court taking up relatives’ demands that the still-unnamed dead be recognized. Today in AfricaMuseum their names are inscribed on the huge windows of the ‘Transit-Mémoire’ corridor. When the sun hits these windows the shadows of their names are projected onto memorial panels engraved with the names of Belgians who died in the Independent State of Congo from 1876 to 1908, in an artwork by Freddy Tsimba entitled Shadows (2018).

Today, a new building has been added to the classically-styled structure of the former Royal Museum of Central Africa. This second space is designed as a public space and for research, education and exhibitions. Together, both buildings make up AfricaMuseum, which since its inception, is not only the largest European museum of artefacts from Central Africa, but also a museum of natural history - which has developed a curatorial emphasis on biodiversity. It is also a large research and training centre with 80 permanent researchers in the fields of biology, anthropology, history and geology, working in more than 20 African countries and teaching around 120 African trainees per year. This exceptional situation posed a huge challenge for the renovation. It was not only a question – and this alone would have been a major task – of reformulating a museum that until the early 2000s, from a curatorial point of view, was the last colonial museum in the world. As well as this, a whole scientific culture of knowledge production and collection management had to be rethought, as well as the institution’s cultures of cooperation and development. Turning this challenge, with all its potential problems, into an opportunity for wholesale reform was undoubtedly a gamble. In thinking about how the renovation could take place in an integrated and participatory manner, the museum’s greatest asset was precisely the diversity of the people who comprise such a large institution. In the frame were not only the various scientists but also the many collaborating Congolese and African experts. There were also several associations – or members of – the Congolese diaspora in Belgium involved. Many artists were also invited to create works inspired by visits to the museum archives, in order to connect the collections to present. So, for example, the visual artist Sammy Baloji has developed a new narrative from the colonial-era Congolese landscapes and photographs of Congolese people. By superimposing these images, Baloji produced another narrative of the archive that interrogates the present, such as in his series “The Past in front of us”. AfricaMuseum’s interdisciplinary conjunction establishes a dialogue between scientists, curators, artists, activists and managers. They have devised a strategy of renovation and a new methodology, permeated by the debate, that seeks to generate a new museological vision for exhibiting these types of objects. This approach condemns colonialism, which it reads in connection to independence, as part of a wider historiography of the territories concerned. This vision has revised museological approaches to the colonial period in a both historical and contemporary way.

The Belgian and Congolese artists involved show us the difference between the past as such and the contemporary interrogation of that past. These artists constantly figure the present as an inheritance, memory or reality. For them, the question of how to represent the contradictory present is the subject of contestation.

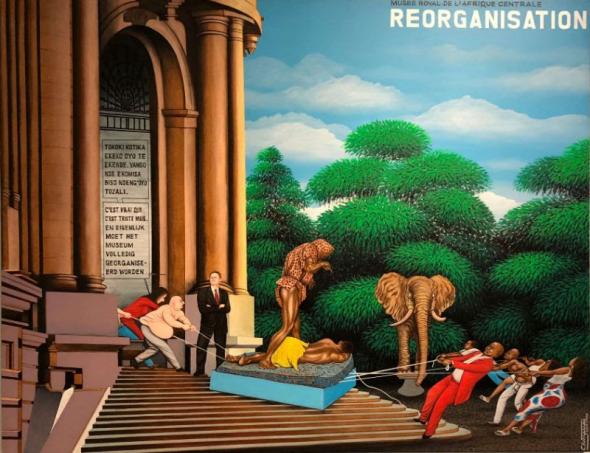

Photo of wall painting Réorganisation, of Chéri Samba (2002), at AfricaMuseum | 2018 | photo by MEMOIRS

Photo of wall painting Réorganisation, of Chéri Samba (2002), at AfricaMuseum | 2018 | photo by MEMOIRS

This is the case in Chéri Samba’s “Réorganization” (2002), a work that epitomizes the differences of opinion, debates and dialogues that comprise the museum today. It has been placed alongside a series of overtly racist and stereotyping colonial statues (including Paul Wissaert’s famous L’homme-léopard (1913)1).

Following intense debates, three options emerged for the museum’s “reorganization”. First, there was the possibility of clearing the museum’s contents and reopening as an empty museum. Second, there was the option of destroying the museum and building a new one. The third tabled choice was to come up with a reinvented museology that would engage with the museum’s history to present a critical view of colonialism, through multiple voices, from the perspective of the present. The third option won. The permanent collection was “reorganized” by theme, sometimes using traditional exhibition techniques to reuse the space of the original museum, and sometimes deploying contemporary forms such as video, sound supports, and pedagogical film. Particular attention has been paid to the Congo’s vast geography, either by bringing forward its abundant resources, its rich biodiversity, or its long history. The connections between this history and the country’s immaterial inheritance have been emphasised: linguistic diversity , rituals and ceremonies, music, literature, art and the presence of the African diaspora in Belgium. Disciplinarity has been brought up to date and interdisciplinary is the dominant logic underpinning the organization of the permanent collection. Particular care has been given to the semantics of the wall captions, and explaining the origins and utilitarian, ritualistic or artistic functions of the exhibited objects.

In the context of wider discussions about the restitution of museum works, questions emerge throughout the space of AfricaMuseum about its profound relationship with the contemporary moment. These are questions that will also have been raised by each team and every Belgian or Congolese artist or citizen who worked there so intensely for so many years.

Questions of restitution

In the last two decades, an urgent interrogation of African, Asian and Latin American artistic and cultural heritage in Europe has burst onto the scene. In the words of Abdou Latif Coulibaly, a historian representing the Senegalese Minister of Culture at a seminar in Brussels in September (“Sharing Past and Future - Strengthening African-European Connections”, organised by AfricaMuseum and by Egmont - Royal Institute for International Relations), these interventions problematize the situation and call for an end to a “forced exile.”

Much artistic work has insisted on the urgency of continuing to decolonize politics and the arts. Ângela Ferreira’s installation “A tendency to forget” (2015) critiques the anthropologists António Jorge Dias and Margot Dias’ claim that their field work in colonial Mozambique was apolitical. Abderrahmane Sissako’s film “Bamako” (2006) confronts us with ordinary citizens who take international financial institutions to court over the African continent’s state of indebtedness. The 2015 Documenta festival in Kassel denounced the genocides provoked by civil wars. Kader Attia’s performance at the Georges Pompidou Centre in Paris demanded the restitution of artworks in exile. The artist Barthélémy Toguo has worked on migration.

In the same vein, in May 2018, the Congolese artist Faustin Linyekula put on the play “Batanaba” in the grounds of the then- Royal Museum of Central Africa, still closed for renovation. Through a residential project at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, Linyekula had found a small Lengola statue in the museum’s warehouses. His mother was Lengola. He undertook a journey with his family, travelling to his mother’s village. The play stages this return trip to her family home in Congo, in search of the statue’s silenced story. The underlying questions are political and ethical: how did this object get to the New York museum? How can the protagonist and his country rebuild when parts of themselves are silent, scattered throughout museums, houses and European galleries?

As is the case with so many other European museums whose large collections are seeped in histories of expansion and colonization, the questions that arise today are no longer only from within these institutions, no longer only rhetorical and self-reflexive. Questions are posed also from the other side: from the side that has inherited the exploitation. Today, this perspective is also represented in the museum by disturbingly interrogative works of art give us tentative access to diasporic and African voices. As black guides lead us through the museum, through objects that look like them and that interrogate both the uncertain memory they have acquired and their precarious belonging, a consensual mourning begins in homage to heroes of independence. It is therefore necessary to understand what these objects mean to their most direct heirs. More work needs to be done on this problem, for certainly many people are unaware that in European museums and university departments lurk not only many objects severed from their original history, but also skeletons, skulls and parts of unburied African bodies.

There is a long history of appropriating bodies, objects, works and archives. This goes far beyond the classical idea of taking the spoils of war. In modern times most of the works that are now being reclaimed were appropriated in situations of violent occupation in the context of imperial expansion. The earliest recorded episode is the theft by the Spanish military of 4000 “green feathers” of the goldcovered quetzal bird that belonged to the court of the Aztec Emperor Montezuma Xokoyotzim. Until today those pieces have been kept at the Vienna Museum of Ethnology, and the Austrian government refuses to them return to Mexico, claiming they are too fragile. A set of codices from the same period were brought to Europe and their names were changed so that they could not be identified. Colonialism legitimised this practice through its soldiers, colonial administrators, explorers, missionaries on the grounds that ownership of territory implied possession of all resources, people, and goods. This fed fetishism, demonstrated power and served to organise Western knowledge, as well as providing a very profitable trade which financed Europe and on which it thrived. But independence did not end this practice of appropriation. Indeed, in many countries, this illegal appropriation of works increased postindependence, particularly in Africa. It has been documented that in Ghana and Nigeria, for example, about 60% of works with patrimonial value were taken post-independence. This situation was due to conflict and civil wars, to the destruction of museums or places of worship, and to the corruption and devaluation of these works by various political regimes that undervalued, and even denied, ritual practices and objects of ancestral popular culture.

There is also a long history in relation to the reclamation of works and archives obtained in colonial situations of conquest or occupation2. These petitions began in the eighteenth century, admittedly with few results, but they chimed with abolition and attendant demands for reparation, particularly by anti-imperialist groups. It was the independence of Southern and Latin American countries, however, that put more pressure on former settlers to return works, body parts, archives and specimens. This RESTITUTING ARTWORKS: A DECISIVE STEP IN THE PROCESS OF DECOLONIZATION 7 wasn’t just on the Europe-Africa axis. For example, in 1990 the United Kingdom returned to Australia a velvet folio of its independence document. In 2005, Italy returned to Ethiopia the Obelisk of Axoum which had been taken by Mussolini in 1937. In 2004, Japan returned to South Korea a sculpture taken during the protectorate. In 2011, 4,500 pieces of pre-Columbian ceramics were returned to Costa Rica. They had been stolen by a New York fruit import company and had become part of the Brooklyn Museum in New York’s collection. In 1955, the Democratic Republic of Germany returned ten of the “Boxer flags” to China. These returns are intermittent and in most cases have only been made possible by diplomatic negotiators. Almost always they are described as gifts, not returns. Yet these and many other examples show us the global dimension of the problem of return / restitution and also its NorthSouth significance. Works stolen from Jews by the Nazis, which now the German state or private entities are returning, are an exception in this sense. Today it is estimated that there are 500,000 works from African territories in Europe.

Between them, the Quai Branly Museum, in Paris, and AfricaMuseum, in Tervuren, hold 210,000 pieces: 42% of the African collection in Europe3. The question of restitution in the case of the Democratic Republic of the Congo is relevant to all African countries. Recent initiatives taken by the French following by President Emmanuel Macron’s statements in the Burkinabè capital Ouagadougou accelerated a process which Nicholas Sarkozy, had started in the opposite direction. In his much-discussed speech in Dakar in July 2007, Sarkozy, a guest, aggressively praised the benefits of colonization and criticized the stagnation of the continent. The considered, serious and lengthy response by twenty-three African intellectuals published under the name of L’Afrique répond à Sarkozy - contre le discours de Dakar (2008) [Africa responds to Sarkozy – against the Dakar speech], took the conversation to another level, leaving Sarkozy, and those who agreed with him, mute. Macron broke this silence, either by diplomatic skill or by a desire to mark a new phase, offering concrete statements on the question of restitution. Macron also consulted experts such as the Senegalese Professor of Economics, Felwine Sarr, and the French art historian, Bénédicte Savoy. The report they produced was recently published under the title Restituer le Patrimoine Africain4 [Restituting African heritage], while Senegal announced the inauguration of a large pan-African museum - Musée des «civilisations noires» [Museum of “Black Civilizations”], in Dakar built in cooperation with China. In Congo, the issue of restitution is not new. In fact, it was already being discussed at the height of the colonial era, when the Museum of Indigenous Arts was created in 1936; at independence in 1960; and with the creation of Zaire in 1973. It was in this frame, supported by Mobutu’s policy of a return to authenticity, that the association of the National Museums of Zaire RESTITUTING ARTWORKS: A DECISIVE STEP IN THE PROCESS OF DECOLONIZATION 8 arose. The first object was returned in 1976, despite Tervuren’s successive attempts to argue that Zaire lacked the appropriate space and infrastructure to receive it. Belgium subsequently returned various types of objects: objects from the museum of indigenous villages from the 1958 exhibition; objects from Rwanda; objects that technicians trained in Tervuren took to the Congo. But unfortunately some of these objects were stolen and entered the art market5. From then on there were no more requests. Today restitution is a real question again, with historical bases. Days before AfricaMuseum was reopened, the DRC President Joseph Kabila told the Belgian newspaper Le Soir that he would start filing new restitution applications in May, a month before the opening of a new Congolese museum has been built in the capital, Kinshasa, with support from South Korea.

The question is very complex and requires a positive attitude on both sides, as well as a good methodology and an analytical framework capable of dealing with different situations. Jos van Beurden’s Treasures in trusted hands – negotiating the future of colonial cultural objects, is highly pertinent here. Beurden offers a typology for categorising objects based on their origin. He suggests five categories: gifts to colonial administrations and institutions, to churches or to the Vatican; objects obtained during private or State or Crown expeditions; objects obtained in military expeditions; objects obtained by missionaries. Beurden also delineates five categories for how an object was acquired: by purchase for an equivalent value; by purchase in accordance with colonial legislation, and therefore for a small amount; by acquisition in violation of the legislation and for a lower value; by theft or coercion.

General frameworks are obviously limited when dealing with such a delicate and sensitive subject. Nevertheless, Beurden’s analytical framework should be useful in determining a common European position on this complex problem that affects all the old colonial metropolises. A shared EU policy, capable of offering a transnational legislative framework whilst respecting the specificities of each country and of each case, is needed here.

Today the changed name of AfricaMuseum reflects its desire – even its need – to change its identity. From a mostly ethnographic museum, it seeks to become a museum capable of taking charge of cultural materials from another place. Nevertheless, whether because of the objects themselves, or because of how they were acquired and travelled to Europe, or even because of geographic dystopia, this changed name heralds a new order. In this new order, the issue of restitution has returned, and has come to epitomize the desires, resentments and frustrations of many. Restitution also has come to stand for badly-handled relationships, and above all, a desire to tell other stories, in other places. These are signs of a complex Europe to rid itself of the past, to decolonize itself from its former colonies, to free itself from the images of the former colonizer and ex-colonized to look at the ghosts of its museum pieces. As such these are signs of a Europe which, in re-examining its national narratives, imagines another future. On the African side, there are also many challenges. For example, as the historian Amzat Boukari-YaharaS has highlighted, the issue of restitution tends to relate to existing African heritage in Europe, classified as assets by European institutions. There is, however, also a need to consider African heritage in Africa, which has not been classified, but should be. This does not change the fundamentals of the problem as Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy lay it out in Restituer le Patrimoine Africain. It does, however, compact the problem of restitution and complicate the question of what heritage is and who it is for. It also presents another, post-colonial, challenge to African institutions. AfricaMuseum’s position on its collection also changed during the renovation. It has identified and listed all its works and says that, if requests for restitution are made, the museum will, subject to certain conditions, return them. Other museums, archives and institutions must now do the same. There should be no doubt on this point: works unlawfully brought to Europe, to the United States or any other country must be returned when claimed by the State-heirs from which they originally came. How this can be done, and particular problems such devolution presents, should be analysed on a caseby-case-basis.

Often the works that we are talking about here, that were acquired illegally or through violence, are in private collections (the most difficult to identify and locate). Many of them - most of which are held by art collectors and in museums of ethnology, science, anthropology - are considered by their former owners to be of inalienable symbolic, identitarian and cultural importance. There are also the skulls and skeletons of unburied people who, for various reasons, are today part of scientific collections. One example is Saartjie Baartman, whose remains were returned by the Musée de l’Homme in Paris to South Africa as a result of one of Nelson Mandela’s first diplomatic initiatives as South African President. There are broadly three positions regarding the restitution process. First, a legal position appealing to the legislation in many countries that enshrines State assets as inalienable. In the second scenario, authorities claim ownership of the works, but point out the lack of equipment to receive them. Finally, the most pragmatic position is the result of productive negotiations. For example, the Dutch government and museum directors have listed and identified works from Indonesia, and agreed to return: a) objects brought unduly, b) objects of symbolic cultural importance. Beyond this classified heritage – designated as such by European experts with their own concepts of heritage – there are other cultural objects that escape the purview of the European canon but that others claim as their heritage. This basic dilemma requires cultural negotiation between multiple parties. Part of the opposition to this process of restitution comes from those who fantasize about future empty rooms in European museums. Such a situation might help us understand the mourning of clans, nations and religious communities stripped of their possessions for centuries. But it is also necessary to take into account that many ritualistic or utilitarian objects were only preserved for many years among tribes or nations because of the care with which they were treated. As such, the point is not that all objects should be deposited in villages or in the care of tribal chiefs - as these communities are often caricatured - but that there are options for conservation and exhibition that go beyond the usual repertoire of a museum. Museums, in turn, should seize the opportunity to reconsider their role and their increasingly commercial institutional models. In any case, for effective and successful restitutions to happen, the over 500 museums that already exist in Africa (that, of course, vary) will need time and good management. A final dilemma is related to the return of archives. In particular, there is the question of who will own the originals of documents that have begun to be digitized. Here, the principle must be the same: the original documents of the stories of an ex-colonized territory and the lives of its citizens must be kept in the national archives of the State that claims them and the digitized copies must be shared with those who want to use them (for good reasons). But in this process of restitution there are ultimate responsibilities to be shared by all the states involved. States must commit to taking good care of the objects and archives returned to them by investing in their preservation and dissemination. At the same time, a fundamental investment in education and in the production of new interdisciplinary narratives is needed to revisit nationalist and colonial histories, and to produce a global history.

During the several years that it was necessary to reform and organize the Royal Museum of Central Africa and transform it into the AfricaMuseum, a scientific council followed the whole process, raising questions whose answers engendered new, sometimes embarrassing, questions, many of which remain unanswered. As uncomfortable as they may be, they are necessary questions that must continue to be asked.

MEMOIRS is funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (no. 648624) and is hosted at the Centre for Social Studies (CES), University of Coimbra.

- 1. Hergé, the well-known author of Tintin, exploited precisely this image of the Leopard Man in Tintin in the Congo. The legal proceedings brought by a Belgian Congolese citizen against the book is an example of the beginnings of a discussion of the colonial question in Belgian society. Another example is Adam Hochschild’s King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa. Consider also the actions of the Belgian Foreign Minister Louis Michel, which, following a parliamentary inquiry, led the Belgian state to present an official apology to the family of the young Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba, assassinated on 17 January 1961.

- 2. See Jos van Beurden, Treasures in trusted hands – negociating the future of colonial cultural objects, Leiden: Clues Interdisciplinar Studies in Culture, History and Heritage, Sidestone Press, 2017.

- 3. These figures come from Felwine Sarr e Bénédicte Savoy, Restituer le Patrimoine Africain, Philipe Rey/ Seuil, 2018.

- 4. Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy, Restituer le Patrimoine Africain, Philipe Rey/ Seuil, 2018.

- 5. This and many other issues were discussed in the BOZAR debate in Brussels on 11 December, “Table Ronde: Les Musées En Convers(At) Ion. Perspectives Congolaises sur la Restitution des Biens Culturels et la Transformation des Pratiques Muséales en Afrique,” [Roundtable: Museums in Convers (At) Ion] organized by AfricaMuseum & Waza Art Center (Lubumbashi, RDC) within the framework of the Voix Contemporaines Echos Mémoires (VCEM) network, following a workshop organized by Goethe - Institut Kinshasa.