The arts have arrived in some parts of Africa, but it took such a long time

The film “Apnée”, by the Moroccan director Mahassine El Hachadi, was awarded the prize for the best short film at the Morocco Film Festival in December 2010. And it received this distinction amidst all the glamour of Ouarzazate, in the presence of Martin Scorsese, Malkovitch, Harvey Keitel and other celebrities, who had agreed to travel to this Moroccan city. The winning film was chosen from a group of eighteen Moroccan films produced in 2010.

The film “Apnée”, by the Moroccan director Mahassine El Hachadi, was awarded the prize for the best short film at the Morocco Film Festival in December 2010. And it received this distinction amidst all the glamour of Ouarzazate, in the presence of Martin Scorsese, Malkovitch, Harvey Keitel and other celebrities, who had agreed to travel to this Moroccan city. The winning film was chosen from a group of eighteen Moroccan films produced in 2010.

At the same time, there is already talk of “Ouallyood” in reference to this recent phenomenon of Ouarzazate becoming not only an important venue for film festivals in North Africa, but also for the production of many films that have been shot in and around the city.

When this newspaper is published, Cape Town will already be hosting, at one of the world’s finest visual art galleries, the exhibitions of “Arcadia” by Deborah Poynton and an excellent selection of 47 photographs by the legendary Billy Monk, taken in the nightclubs of this city between 1967 and 1969. How far removed we now are in these two African countries (and, in fact, in so many others) from that moment in 1906 when, in the company of Matisse, Picasso discovered African art through a white Fang mask from Gabon, and, although he had never been to this continent, declared himself to be a great fan and supporter of ‘African art’. We are also far removed from the First International Congress of Black Writers and Artists organised in Paris, in 1956, by the journal Présence Africaine, with the support of UNESCO. Attending this event were black historians, poets and thinkers, such as Amadou Hampâté Bâ (Mali), Léopold Senghor and Cheikh Anta Dipo (Senegal), Marcus James (Jamaica), and even the mythical choreographer and dancer Josephine Baker, who also visited the conference. They demanded world recognition for their work and demonstrated the artistic quality and intellectual excellence of their thinking. They were also to be the pioneers of a culture that was negotiating its mental and ideological decolonisation, as well as the standard bearers of many utopias that they were claiming for the African continent. Regardless of what actually happened to the independence movements in the wake of this conference, and which ended up greatly disappointing these protagonists themselves, there is no denying that many of them, as well as a number of others, quite justifiably formed the basis for the narratives that were being formed about the cultural history of Africa in the 20th century.

Since the 1960s, there has been great excitement in many African countries with the creation of art schools. Together with the first exhibitions of self-taught artists, there have also been the first festivals of black art, and even the work of African photographers has begun to establish a reputation for itself in Africa, in European countries and in some forums in the USA. The history of these artistic movements is already being written, describing their schools, their leading figures and their international impact. Yet one thing remains certain: this history has not been the same everywhere, varying according to the country in question, the nature of the ex-coloniser, the greater or lesser presence of self-taught artists and writers, as well as the decision about whether to write in universal or local languages, with different impacts on the international literary community. Today, this unequal situation to be found between the artistic scenes of African countries is a fact.

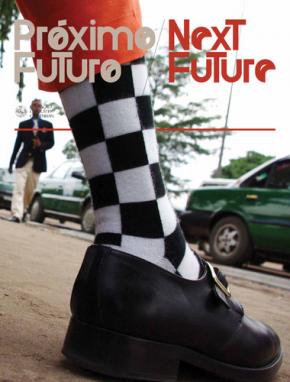

Today, one can come across a movement of artistic posers the like of which has never been seen anywhere before (such as the sapeurs – some dandies who can be found in Brazzaville and Kinshasa and are unique in the way they turn clothing and posing into a movement of urban social creativity), in much the same way as, in Sudan and solely as a matter of perseverance and obstinacy, one can find the photographer Ali Mohamed Osman working in the midst of chaos and civil war.

It is known that there is no direct relationship between economic development and artistic and cultural creativity. However, without a market and without financing, artistic creation, training and production are not possible, and in those few countries where only the barest minimum has been provided the result has been very positive. We also know that there is a direct relationship between cultural creation and the way in which it has been received in regimes where democracy has been installed. The best examples of artistic production in African countries clearly illustrate this fact. When these two components come together, the result is mainly a positive one. There are, of course, exceptions, which normally derive from other factors that are not always easy to explain or from causes that are not immediately visible. And part of this same problematics also applies to the traditional African arts. There is an enormous amount of work still to be done both about these and for these: research, criticism and inventorying, using new methodologies and techniques, and, above all, operating from a less dogmatic perspective in relation to the understanding of the colonial period and, in particular, the pre-colonial period. Just as there is also an imperative need to catalogue the old works, which are to be found in their presumed places of production and conception, such as museums, institutions and collections outside Africa. This is an ethical imperative and an action of incalculable artistic value.

Today, there is a new geopolitics of the arts in Africa, with examples being provided by the production of an extremely vast group of exhibitions, festivals, performances, concerts and books. And there are programmers and producers who, in many African, European, South American and North American countries organise events with either original creations or others from the African Diaspora for people to see and listen to. In Portugal too, after decades during which a certain distance was maintained, new generations of cultural agents and artists have, I sincerely believe, made a great contribution to this phenomenon. Within the limits of its possibilities, the Gulbenkian Next Future Programme is enormously proud to be a part of this international movement of cultural negotiation with Africa.

download PRÓXIMO FUTURO