Luanda, Lisboa, Paradise?

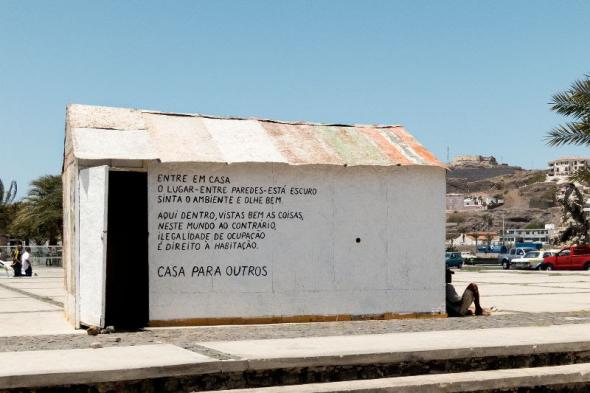

Casa para outros (instalação Ocupações) | 2013 | Diogo Bento (courtesy of the artist)

Casa para outros (instalação Ocupações) | 2013 | Diogo Bento (courtesy of the artist)

The end of the European overseas empires in the wake of decolonization was accompanied by armed conflict and insurrection. In the 1960s, 70s and 80s these processes brought significant population flows to Europe. These were marked by displacement, ambiguity and integration, but also by fractures, exclusions, segregation, invisibility, trauma and new and complex identities: the repatriated, pieds noirs, Portuguese returnees, veterans of colonial wars, former colonizers, former colonists, refugees from civil wars, immigrants. Since then, we have seen the emergence and consolidation of a remarkable activity in the visual arts, the performing arts, cinema, music, dance and literature. This has been led not only by the generation that lived through the events – for whom processes of deterritorialization most often elicit a testimony of trauma – but also by the children of these former empires. They re-interrogate the rupture that they lived through as children – or, indeed, trauma that they did not live through because they were born later. But they also explore other stories: of their parents and grandparents’ origins, and, through them, of their countries. Djaimilia Pereira de Almeida’s Luanda, Lisboa, Paraíso (Companhia das Letras, 2018) [Luanda, Lisbon, Paradise] has just won the 2019 Oceans Prize. It is a Portuguese affirmation of a literary lineage of European scope – afropean, as it has come to be known in English, or afropolitan, in French. These terms name identities inherited from colonial processes with continuities in contemporary Europe. They help inscribe Almeida’s work in a Portuguese literary genealogy of imagining, and questioning, the place of Portugal in Europe (1).

Luanda, Lisboa, Paraíso describes the journey, in the colonial period, of the Angolan Cartola de Sousa, who lives in the small town of Quinzau, in Angola. He travels to Luanda, where he marries. He later moves to Moçamedes, where he becomes an assistant nurse to the Portuguese doctor Dr Barbosa da Cunha. The journey then takes us to post-colonial Lisbon, to the outskirts of the city where many African immigrants made their homes. This is the antiphrastic Paradise of the title. It is at once reality and metaphor. The narrative focuses on a figure widely represented in the Portuguese colonial imagination, but little treated in Portuguese literature. Who is Cartola de Sousa?

In Angola, in the colonial period, Cartola de Sousa had a typical life of an assimilated African petty bourgeoisie. We get a glimpse of this in the novel. He has fond memories of a time when he was young and his life had a certain kind of order. He had social and professional status. He could live peacefully and convivially, and dream of social advancement in the way perversely granted to the assimilated:

“Neither sleep nor dullness sullied the first perfect evening of Cartola de Sousa’s life. The children played with a wooden horse. The women compared crochet patterns. On the porch, the men smoked and drank warmed brandy. The male midwife was gradually forgetting his shame that the doctor had realized he was copying his ways. The doctor was delighted: imitation, after all, is the highest form of flattery. Seen from the street, the indolent, silent choreography of the scene was both beautiful and tragic, auspicious and funereal. Through the linen curtains falling across two tall windows, the shadows of the four adults performed a dance within a frame, in a house like an oil painting, out of time, beyond where exemption may rescue that which does not have to apologize for its own sweetness.” (Almeida, 2018: 44. My translation)

In effect, this world, full of the marks of ending, would come to undo itself: Dr Barbosa da Cunha returns to Portugal. Cartola de Sousa watches the departure of the Portuguese expectantly, celebrating independence with a contained joy. His family begins to disintegrate. Achilles is born, and named for his defective heel. His mother is immobilized and bedridden. In the wake of independence, the house of Cartola de Sousa becomes haunted by a disease which would always determine his and his family’s life.

In the 1980s, following the route of many African citizens from Portuguese-speaking countries, Cartola de Sousa travels to Lisbon with his 14 year-old son Achilles. They leave so that the boy can receive medical treatment and undergo surgery which will, in theory, cure him. Glória stays in Luanda, stuck to her bed and cared for by Justina, their daughter. The journey to Lisbon brings a series of dreams to the surface. They range from the practical – how to solve a child’s illness – to the illusive – finding a city that would welcome you as an already assimilated Portuguese man, who had dreamt of the Lisbon of postcards, imagined all white people were like Dr Barbosa da Cunha, and dreamt of himself as Portuguese. In truth, nothing, and no-one, awaits him in Lisbon. Contacts with Dr Barbosa da Cunha quickly dissolve to nothing. He lies to himself about the papers that would identify him as Portuguese.

Achilles’ problem is not resolved despite various operations. Luanda, left behind, becomes merely a series of petitions, and the distant voice of Glória. Achilles turns 18. Their hopes fade in an inhospitable city. Cartola de Sousa and his son fall into the same fate of many Africans arriving in the city. They traipse between the hospital and their cheap Casa para outros (instalação Ocupações) | 2013 | Diogo Bento (courtesy of the artist)lodgings. They fall into debt and share a common unhappiness. They end up in Paradise, a neglected, insalubrious neighbourhood. Father and son are thrown into a round of physically exhausting daily life, punctuated only by distant contacts with Glória, who becomes – like Luanda, like Angola – a pure and distant abstraction. This more or less unhappy existence is commingled with the friendship of a Galician, Pepe, poor like them, but the owner of a small shack of a bar. It is interrupted by the visit of Justina from Angola, who reconfigures the poverty of their household. There is the constant presence of a suitcase that comes with them wherever they live; a suitcase that is almost always packed. It feeds the vague idea of a delayed return. It is full of objects and papers which safeguard a former life in which Cartola de Sousa did not have to apologize for being happy. In Lisbon, it reveals to him his lost status, translated into a pile of useless papers. Achilles, the son, on the other hand, is a child of independence and an Angolan immigrant in in Lisbon. He misses his mother, and Luanda, and is struggling for a better life. Cartola de Sousa carries with him a phantasmagoric identity which disappeared with the end of the colonial period. It was an identity connected to a dream of Portugal as a good place, to which he too belonged. Still, his life in Portugal reveals the perversity of assimiliationism to him at every step. What connected Cartola de Sousa to Portugal was a fantasy. The recognition of his belonging would always be, as in colonial times, a delayed, tragic farce. What exists is the reality that he was expelled from Angola. His subaltern condition is reaffirmed by where he lives – the periphery called Paradise –, by the devaluation of his professional skills, and by the exploitation of his black body as labour power. It is reaffirmed by the poverty from which he cannot escape, and by his continuing invisibility in the urban life of Lisbon. How often did the Portuguese people who visited Expo 98 and those new Lisbon neighbourhoods along the Tagus, and who, twenty years after decolonization, again celebrated the Discoveries, think of the colour of the labour that built it? How often, in the Metro Underground, do the Portuguese look at working men with tired faces, paint-stained clothes and dark skin and see them as those who built the Portugal of today? Who are we, the post-imperial Portuguese? And Djaimilia Pereira de Almeida does not ask this question only to the Portuguese. In the end, what is it that independence brought for Angolans, for this Angolan family? The journey here is also one of loss: Cartola de Sousa lost his social and professional status; Glória is bedridden from independence on, playing out a fantasy that is more unreal by the day; Achilles will always be the “lame black boy”; Justina returns to Luanda and we hear no more of her. What is real is Paradise, the misery of the father and the son. A universe only softened by the brief stay of Justina, by happy moments with Iury, by the rough friendship of Pepe; all marginal and disposable people. And even this world of an apparent “cosmopolitanism of the poor” (2) will disappear: Justina departs, the poor house they live in burns down, Iury collapses, Pepe dies. Cartola mourns for his friend, without power and without hope. He is a survivor: (3) Cartola found himself in Rua Augusta and carried straight on. He carried himself like a deposed chief, crowned. Up to then it seemed that no-one had noticed him, but a boy pointed in his direction and said, “Look, Mother, a magician” […] The new top hat stuck out like a sore thumb, not because it didn’t suit the man, but because it didn’t suit the present. Under the arch of Rua Augusta, those old postcards of the metropolis came to his mind. He noticed that it looked like a mouth with two throats and that the people marched along the arcades like the joyful meal of a Leviathan. He did not look away towards the Cais das Colunas. Cartola looked directly at the Tagus and granted it a few minutes. […] As the river could not bear to look straight at him or answer him, and simply changed the subject in an ambiguous thud, the man took off his top hat, threw it into the water, and turned his back. (Almeida, 2018: 228-229) In post-imperial Portugal, the question is asked once again by another phantasmatic figure of Portugal. Coming from the interior of the lost empire, the black man D. João de Portugal asks the question again – can it be that Romeiro was also “no-one”? (4)

What is at stake in Djaimilia Pereira de Almeida’s book are the living, human ruins of empire. No longer based on the figure of the veteran or the returnee, but on someone from the other side of the line colonialism traced: a black man and, in this case, the complex figure that colonialism generated, the assimilated African who, here, for the first time in Portuguese literature, is at the centre of the narrative. In the Portuguese imaginary, the Tagus epitomizes all the histories of the Portuguese empire that were launched from there onto the “endless sea”. It bathes the mental metropolis of Cartola de Sousa. It will not respond to him because there is no response to the ruins of empire. There is no possible restitution for a trick and an illusion. What remains is a spectral citizenship of a fantasy world that history has transformed into a phantom. Lisbon does not exist. _________________

(1) See Isabel Lucas, “Djaimilia Pereira de Almeida: não é só raça, nem só género, é querer participar na grande conversa da literatura”, Público, Ipsilon, 20 December, 2018.

(2) Reference is to the title of Silviano Santiago, O Cosmopolitismo do Pobre: Crítica literária e crítica cultural, Belo Horizonte: UFMG Editora, 2004.

(3) See Roberto Vecchi (2018) “Depois das testemunhas: sobrevivências”, Memoirs Jornal, Público, 14 Setembro, p. 18.

(4) A reference to Romeiro, D. João de Portugal, from the play Frei Luís de Sousa, by Almeida Garrett. I deal with this in its context in my book Uma História de Regressos- Império, Guerra Colonial e Pós-Colonialismo, Porto: Afrontamento, 2004.

_________________

MEMOIRS is funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (no. 648624) and is hosted at the Centre for Social Studies (CES), University of Coimbra.