Waiting for the Next Future (II)

Patrick Chabal was one of the well-known figures who took part in the Next Future conferences, ‘Grandes Lições’ [Great Lessons]. At the Gulbenkian Foundation in 2011 he argued that it was a moment of novelty and lucidity:

The future of the West is now inextricably linked to that of the non-West. The environmental issues the world faces as well as the inexorable rise of the economic power of China and other Asian countries make it impossible for the West to consider ‘what comes next’ in the same ways as before. But the challenge is far deeper than the present debate on the ‘decline of the West’ suggests. My lecture will focus on how the postcolonial challenge to the West’s outlook on the world as well as the influence of citizens of non-Western origins living now in the West have combined to expose the limits of what I call Western rationality – by which I mean the theories we use to understand and act upon the world. The growing failure of Western social thought to explain plausibly and to address successfully some of its key domestic social and economic issues, and some of the crucial contemporary tests of international politics, has laid bare the inadequacies of the Western social sciences as they have developed in the centuries since the Enlightenment. What the West needs, but has not accepted yet, is not more and better theory but a new way of thinking. (1)

We are still living through this long moment. In temporal terms the question initially put forward by the lead curator, António Pinto Ribeiro – “Can we intervene in the future, in the coming future? We certainly can” –, has not been exhausted. This aesthetic, ethical and political question determined not only the Next Future programme’s methodology, but its content. This “future” is always a place for seeing things with fresh eyes and in new ways; for re-discovery. It is a space in which to improvise, to innovate, and to attend to the contemporary. For me, indeed, the contemporary is the guiding light of the programme. The contemporary combines distinct elements, disciplines, geographies and artistic forms. Even when these appear to be unconnected, their combination can create something new. Another key word of the programme is cosmopolitanism.

The Honourable Justice Julia Sakardie-Mensah, 2005, Pieter Hugo, Cape Town Cosmopolitan contains the idea that productive mobility is desirable, not problematic. It posits the South “as a nexus of ‘local’ cosmopolitanisms and intracontinental movements and diasporas.” (2) Finally, and definitively, Next Future is post-colonial: the moment in which, from within Europe, we recognize that a great part of Europe’s history took place beyond the continent’s territorial boundaries. If we are going to look for that history, it is not only in the obvious marks that it left, but in the transformations that it wrought, and by which Europe itself has been transformed. Next Future is the moment in which Portugal and Europe came to create the future, face to face with the world, in the 21st century.

The Honourable Justice Julia Sakardie-Mensah, 2005, Pieter Hugo, Cape Town Cosmopolitan contains the idea that productive mobility is desirable, not problematic. It posits the South “as a nexus of ‘local’ cosmopolitanisms and intracontinental movements and diasporas.” (2) Finally, and definitively, Next Future is post-colonial: the moment in which, from within Europe, we recognize that a great part of Europe’s history took place beyond the continent’s territorial boundaries. If we are going to look for that history, it is not only in the obvious marks that it left, but in the transformations that it wrought, and by which Europe itself has been transformed. Next Future is the moment in which Portugal and Europe came to create the future, face to face with the world, in the 21st century.

The curation of this vast and manifold programme was ambitious. It required considerable financial resources and significant administrative, production and implementation capacity, all deployed with imagination and emotional and dialogic intelligence. The programme emerged from a focused, careful and interdisciplinary methodology that articulates two fundamental axes for thinking and understanding the present and thinking about the future. Next Future’s structure articulated lines of debate, thought and theory in the areas of the arts, social sciences and humanities. These were orientated around the “Great Lessons” workshops with national and foreign researchers, including prominent figures such as Achille Mbembe, Elikia M’Bokolo, Homi Bhabha, Arjun Appadurai, Alan Pauls, Gayatri Spivak, Mamadou Diawara, Nestor Garcia Canclini, Ticio Escobar, Lilian Thuram, Kole Omotoso and Patrick Chabal. Another axis of the programme was dedicated to the arts and included dance performances, theatre, music, cinema and visual art exhibitions. Revisiting the programme’s website and browsing its newsletters and blog show that visual culture was registered as a mode of thought alongside more traditional forms of written and musical texts. In the context of the programme, and the spaces, people, worlds and events that it addressed, all these forms were potentially innovative modalities of representation. However, the visual arts in general and photography in particular were particularly important. Exhibitions were dedicated, for instance, to the Bamako Encounters, South African photographer Pieter Hugo and modern Brazilian photography. The immediacy of these visual arts and their ability to establish new images and imaginaries changed public ways of looking at the spaces represented. Finally, I want to draw attention to one aspect of the programme’s success in bringing together of people and creation of spaces for reflection and creativity. This was the ability to produce and stage multiple artistic, theoretical and literary works for Next Future itself. This allowed a group of young thinkers, researchers and artists to begin from their own situations to conceptualize and realize work for the specific platform of creativity and dialogue proposed by Next Future. This crossing and production of distinct knowledges through the participation of young artists not used to working for institutions like the Gulbenkian Foundation led to the use of less familiar spaces within the Foundation itself, such as re-purposing the garage as a venue for dances and concerts. The artists used outdoor spaces, the Gulbenkian’s gardens, and other sites across Lisbon to create forums for dialogue, intervention and pleasure. These were able to attract new audiences and establish the possibility of crafting democracy through art. They offered interculturality as a challenge and not as a threat. They offered the possibility for a Next Future.

Through the spaces it produced for the consumption of art and culture, and the training and creation that it encompassed, Next Future definitively made its mark on contemporary art. We can see the results now in the internationalization and modes of dialogue and alignment within the spaces and geographies on the international artistic agenda. We can see the results also in the persistent presence of many of the thinkers involved as artists and writers in the European – and global – contemporary cultural scene. António Pinto Ribeiro argued, in his assessment of the programme in 2011, after three years of its existence, that “meeting with and learning from cultural protagonists from Africa and Latin America has allowed all of us to broaden our horizons and better understand the world.” (3)

An initial question remained unspoken, but it underlies the programme: in the West, how can nonWestern arts be understood beyond the paradigms emerging from the colonial world? Some answers to this question have arisen. One of the major methodological and ethical challenges of the programme itself, and the significant shift that it has introduced, has been achieved: to show the works and their authors not as Africans or as Latin-Americans, but as artists, thinkers, and producers of knowledge. The second was to grasp their works – in the visual and performative arts, in cinema, in literature and in music – as capable of making the transition between a European, still colonial, perspective on these spaces and subjects, and the new, the urban, the chic, the cosmopolitan and the modern of Latin American, African, or black artists. This places these artists between on the one hand a political affirmation of difference within Northern societies, and on the other an exultant fretfulness in their own societies, themselves in the midst of deep processes of self-discovery, re-creation and decolonization. Although it was not set up thematically, beyond the indisputable quality of the works and the curation that made up the programme, a number of topics emerged which anchored the new course it set out: frontiers, identities, memories, cities, mobilities, migrations, resistance, crises, new economies of production and contact zones. These themes – as ongoing interventions and interrogations – defined new perspectives on new spaces.

And what experience emerged from this perspective? Among other things, the ability to better understand the world. For instance, faced with a moment of revolution and novelty such as the Arab Springs in the Maghreb, Next Future had the curiosity and the ability to reinvent its own programme and propel itself forward into a new world. This responded to a demand to understand what was happening in a part of the world that was at once so near and so far from Western Europe. This required understanding and unravelling centuries-old stereotypes, and to deal with the great phantom of the West: Islam. Finally, the translation into Portuguese of the beautiful poem “Casa”, by Warsan Shire, a kind of exegetical dialogue with the West over the drama of the refugees, shows how the theme of the West and the Maghreb needs to be approached in a programme such as Next Future, if it is to match an ambition to put forward a new perspective on the contemporary. In 2012 Next Future hosted Maghreb and its contemporary creativity in design, fashion, literature, thought, cinema and music. The region’s artists’ mobility is oriented towards Europe in general and the South of France in particular. It has resolutely marked the French artistic and literary scene. In the remit of this programme, in Portugal, such geographies of mobility carved out a space for discussion of shared histories, anxieties and dreams in a period of both rupture with an oppressive past and also an uncertain, problematic future.

https://www.buala.org/sites/default/files/imagecache/full/2019/09/pefut1..." alt="from series Tunisian Revolution | 2011 | Ons Abid

" width="590" height="386" />

From 2013 to 2015 Next Future entered a new phase of reflection. The 2013 programme began with the conclusive and unsettling words of the South-African bishop and Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, Desmond Tutu, at a conference at the Gulbenkian Foundation on world peace and sustainable development. There Tutu declared: “I’m sorry to tell you, but we are all Africans”. (4) Tutu was partly responsible for one of the most productive, democratic and human mechanisms of post-conflict justice, the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commissions. Tutu spoke, from Lisbon, to the hearts of all Europeans. He spoke not only of how his declaration required a transformation of unquestioned narratives, but also of his own, African, humanity. He introduced the theme of sustainable development under the sign of historical misconceptions, and resolutely within the framework of narrative power. He appealed to the historical and ethical responsibilities of Europeans not only to think about mechanisms of restitution and cooperation, but above all to listen, now, to others and their narratives. Only by listening can we stop discrimination, subjugation, racism, exploitation and the destruction of people and civilizations, from repeating themselves again in the future. Only thus can there be a sustainable future for all humanity. Sustainability, therefore, must be articulated not only in economic, political, social and ecological terms, but in philosophical, psychological and symbolic terms too. This was the necessary commitment to a Next Future on the part of the former European colonizer. Tutu clarified, therefore, what the current President of the Foundation, Isabel Mota, had laid out in her text in the 13th edition of the journal Next Future. There she had written of the “blurred representations” and “clichés” which dominate the relations of representation – and with them, the relations – between Europe and Africa.

It was based on this that the programme put together an unprecedented African show, focussing on a wide variety of artistic areas including cinema, music and theatre, as well as paying close attention to visual culture. This involved showing part of the 9th edition of Bamako Encounters, under the theme “For a sustainable world”, and the exhibition Present Tense, curated by António Pinto Ribeiro. This exhibition featured works by South African photographers such as Délio Jasse, Dillon Marsh, Filipe Branquinho, Guy Tillim, Jo Ractliffe, Kiluanji Kia Henda, Mack Magagane, Malala Andrialavidrazana, Paul Samuels, Sabelo Mlangeni, Sammy Baloji, Tsvangirayi Mukwazhi and Pieter Hugo – to whom the 15th edition of Next Future (March 2014) was also dedicated – along with the international exhibition “This is the place”. I could add other names to this list, such as Kader Attia, Ayana Jackson, Zined Sedira, Neïl Beloufa, Mohamed Bourouissa, Katia Kameli, Nu Barreto, Pauliana Valente Pimentel, Monica Miranda, Ana Vidigal, Francisco Vidal, Nuno Nunes-Ferreira and Tatiana Macedo. Today these artists make up the avant-garde of the European and international art scene. With their intellects, their image making, their courage and their exhibiting skill, these artists have contributed to changing European and Western imaginations of Africa and the Maghreb. They show us their own presents, and those who live, work, fight and love every day in the immense and diverse place we call Africa, made up of so many Africas. Today, as part of the project Memoirs: Children of Empire and European Post-Memories, I seek other perspectives on the former European colonies and Europe. And I find them. For instance, in 2018 I saw Délio Jasse at Maxxi (Museum of Contemporary Art in Rome) and Kiluanji Kia Henda. The sensual photograph “Rochers carrés” (2009) was the frontispiece of Kader Attia’s large exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, in London. That photograph of those children on concrete blocks in Algiers looking back at us across the Mediterranean, was also seen in Lisbon at Culturgest at the exhibition, “Roots grow in concrete too”. In Paris, I have seen Mohamed Bourouissa in the George Pompidou Centre as the 2018 Marcel Duchamp Prize. Nearby, at the Nathalie Obadia Gallery was Nu Barreto’s first solo exhibition in Paris, Africa: Renversante, renversée. I have seen Sammy Baloji at the renovated Africa Museum in Tervuren, Belgium, as well as in Portugal. And I remember that I had seen all of these artists at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation as part of Next Future. I recognize Lisbon as a European capital. I am proud that Portugal is a significant part of the artistic routes of all these innovative artists and their imaginaries, and I am left in no doubt of the international impact of Next Future on the contemporary art scene. Between 2009 and 2015 it was the Next Future, but these artists are, today, composing our present. This brief account of the visual arts would be equally valid for all the other art forms involved in the Next Future programme.

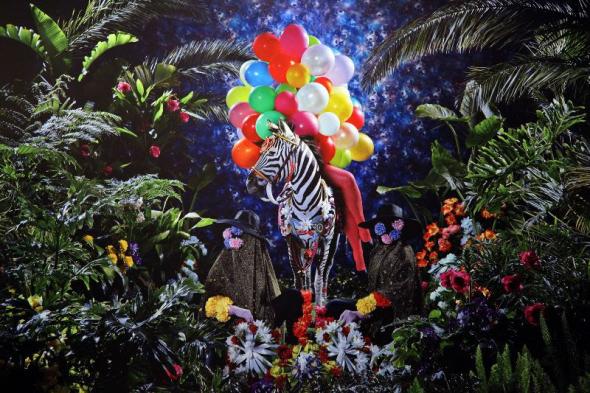

The Night of the Long Knives, III | 2014 | Athi Patra Ruga

The Night of the Long Knives, III | 2014 | Athi Patra Ruga

2014 and 2015 were characterized by cultural programming focussing on Latin America. The programme was consistently topical in a variety of ways, but it is worth drawing attention in particular to the excellence of the theatre presented. It constituted the most important exhibition of contemporary South American theatre in Europe and included the debuts of several renowned actors including Guillermo Calderón, the dance of Tamara Cubas – a Uruguayan choreographer who more than anyone in the field has interrogated the permanency of colonial relations in Latin America, and the epistemicide of indigenous cultures –, and the work of Argentine Lola Arias, an example of outstanding theatre which interrogates the inheritance of the dictatorships, and the questioning of the generations that followed. In “Grandes Lições”, Walter Mignolo wrote of “the mutations of coloniality and contemporary world disorder”. Because of its inability to control the twinned concepts that enabled its supremacy – modernity and colonialism – the West is coming to an end as a kind of reality, Mignolo argued. Issue 17 of the journal was entitled Modernidades: Brazilian Photography (1940-1964). Here Mignolo emphasized this symbolic shift by drawing not on Europe, but Brazil. Europe lay in ruins after the First World War. The United States asserted its modernity and dominance. Brazil went through a unique process of modernization thanks to the arrival of millions of immigrants and with them ideas, labour, wealth, and intellectual reflection that led to the first great synthesis of the 1922 Modern Art Week and, later, the works of Gilberto Freyre, Sérgio Buarque de Holanda, Antonio Candido and the whole artistic revolution of Brazilian modernisms in many areas. How, in this context, could Europe have remained a metropolis of the mind? A multifarious interrogation of the diverse continent of Latin America underwrote the programming of “Contact Zones”, the last programme under Next Future’s banner. Indeed, we can see now that this was also the conceptual stepping-stone towards Passado e Presente – Lisboa Capital Ibero-Americana de Cultura [Past and Present – Lisbon Ibero-American Capital of Culture] in 2017, also curated by António Pinto Ribeiro. “Contact zones” – an expression so dear to post-colonial studies in order to designate the geographical frontiers and areas of social, political, linguistic and geographical interaction – was the theme that drew Next Future to a close. The Mediterranean, from Greece to Algeria and Morocco, and Central America, are the geographical regions of contact and bordering which were highlighted with a festival of thought and literature from these areas. This festival included, too, an extraordinary piece of theatre which I want to highlight: “Vou lá Visitar Pastores” [I’m off to visit Pastores], adapted and directed by Manuel Wiborg based on the text by Ruy Duarte de Carvalho. Vou Lá Visitar Pastores is, in the words of the lead curator, a “kind of world-work”, considering the world from the territory of a greater Angola. Another “kind of world-work” worth highlighting in Next Future was As Confissões Verdadeiras de um Terrorista Albino [The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist]. These Confessions offer a brand of humanism for our times, in which discourses of hate, racism and xenophobia are tucking themselves into the political terrain of anti-humanism. As Lilian Thuram, the World Cup-winning footballer, emphasized to us in a different context through his civic work, the struggle against them must be undertaken every single day. Thuram and his Foundation are committed to the fight against racism through education. (5)

Next Future ended by opening up to the future, with a nod towards a Europe and a Eurocentrism which has hardly considered African and Latin American comic books, crime writing, science fiction or visual animation. A challenge to museums and virtual exhibitions was launched with the project-exhibition Unplace – Networked Art: Places-Between-Places. This was both an example and a lived experience. It put forward the idea of contact zones as spaces of ideas and areas of knowledge, of people and artefacts undertaking transnational and trans-territorial journeys, exercising freedom of thought and freedom of creativity. It set itself radically against the border landscapes that we see in everyday images of the suffering, pain and exclusion of so many. In Mexico these are the landscapes of people trying to cross the border into the United States and in Europe the many who die trying to cross the Mediterranean. They die knocking at Europe’s door, fleeing from the war, underdevelopment and poverty in which we can see, too, the image of European History. Next Future was unique in its scale, its means of mobilization, its cosmopolitanism, and the ethics of its aesthetic commitments. But it was also anchored in an earlier programme which included many international artists, the “Gulbenkian Programme of Creativity and Creation”, curated by António Pinto Ribeiro and Catarina Vaz Pinto. That programme was noteworthy for the substantive analysis of and reflection on the contemporary, published in O Estado do Mundo [The State of the World], which characterized the importance of the moment not as a threat, but as a challenge:This State of the World is designed to be a place where the future is challenged, a place for questioning cultural production and of what seems obvious but is not, where passive acceptance of a “one-way” cultural market is criticised, a place par excellence for current themes and emerging problems that perhaps cannot yet be overcome, a place where the new culture can emerge from discussion (organised into various platforms) of cultural problems and the presentation of a complementary programme of performances, exhibitions and film as examples of the current State of the World.” (6) Next Future was a response to this challenge to create a space of recognition, dialogue and communication which enables each of us to recount our history based on our place in the world and our mode of expression. From there we can touch the world ourselves. It has bequeathed to everyone who participated in it, inside and outside Lisbon, and through the many materials it produced (website, newspapers, blog, books, movies, plays, catalogues, etc.), a new representation of Africa and Latin America. It has left us with a new proposal for how to think about the cultural place of Europe, and with a new way to curate. It has made Lisbon into a stage for the world of contemporary culture in the 21st century.

Thanks to Next Future we understand that North-South and South-South links are forged out of mobility and cosmopolitanism. Dialogue between these links is essential if we are to trace a new cartography of thought and of contemporary art in the 21st century. This is not a question of de-centring the world, but of a polycentric re-centring. Here, horizontality will replace the verticality that cuts up the territorial, political, economic and social organization of the world into metropoles and colonies. This is not a merely fashionable or contextual response. It is a reality right before our eyes that by its very essence questions identitarian and nationalist movements of reterritorialization and closure. Such movements cyclically resurge in European political discourse. They led, too, to the closure of many African countries in the years after independence; years animated by revolutions in which many were martyred, and of which newly independent states quickly became orphans. Bandung, in 1955, showed the world new political actors, outside Europe, discussing the Next Future of the world. It launched a logic of horizontal dialogue against the imposition of an old verticality. Today contemporary artistic discourse demands of us that we remember this history, and this future. What Next Future left above all in Portugal and in Europe was a decolonization of the imaginaries by which art shows us that there are no separate humanities. The 21st century will be Asian, African, European and American to the extent that we can construct the hypotheses that will decide the future. We can do so illuminated by art, with its power to tell us who we are as people and as a community. With its power to trouble us, challenge us, and make us dream. ______________________ (1) Patrick Chabal, “Racionalismo ocidental depois do pós-colonialismo”, 13th May 2011. (2) Ruth Simbao “O Afropolitano: novas geografias na arte africana contemporânea”, Jornal Próximo Futuro, n 4, Maio, 2010, p. 24. (3) António Pinto Ribeiro, “Próximo Futuro três anos”, Jornal Próximo Futuro, n.7, Maio, 2011, p. 5. (4) António Pinto Ribeiro, “Lamento dizer-vos mas somos todos africanos”, Jornal Próximo Futuro, n. 13, Junho/ Julho, 2013, p. 4-5. (5) This programme will be re-staged by the project Memoirs: Children of Empire and European Post-Memories (ERC n. nº 648624) with Lilian Thuram 25th-29th of Novembro in Coimbra and Lisboa, and with the piece The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist, at the Marseille Biennale, 15th-20th October 2019. (6) António Pinto Ribeiro, “Proposição”, in O Estado do Mundo, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian/ Tinta-da-China, 2007, p. 13

________

MEMOIRS is funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (no. 648624) and is hosted at the Centre for Social Studies (CES), University of Coimbra. memoirs.ces.uc.pt